The Exploration of Light As a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

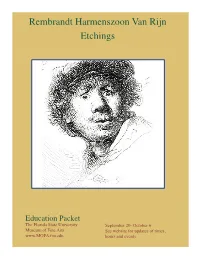

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

THE ICONOGRAPHY of MEXICAN FOLK RETABLOS by Gloria Kay

The iconography of Mexican folk retablos Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Giffords, Gloria Fraser, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 20:27:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552047 THE ICONOGRAPHY OF MEXICAN FOLK RETABLOS by Gloria Kay Fraser Giffords A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN HISTORY OF ART In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manu script in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: Robert M. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Presents the Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, the First Major Exhibition on the Subject in the United States

(Image captions on page 8) (Los Angeles—April 26, 2018) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, the first major exhibition on the subject in the United States. Organized by LACMA in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, this groundbreaking show brings together some 100 rare and seldom-exhibited chiaroscuro woodcuts alongside related drawings, engravings, and sculpture, selected from 19 museum collections. With its accompanying scholarly catalogue, the exhibition explores the creative and technical history of this innovative, early color printmaking technique, offering the most comprehensive study on the remarkable art of the chiaroscuro woodcut. “LACMA has demonstrated a continued commitment to promoting and honoring the art of the print,” said LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan. “Los Angeles is renowned as a city that fosters technically innovative printmaking and dynamic collaborations between artists, printmakers, and master printers. This exhibition celebrates this spirit of invention and collaboration that the Renaissance chiaroscuro woodcut embodies, and aims to cast new light on and bring new appreciation to the remarkable achievements of their makers.” “Although highly prized by artists, collectors, and scholars since the Renaissance, the Italian chiaroscuro woodcut has remained one of the least understood techniques of early printmaking,” said Naoko Takahatake, curator of Prints and Drawings at LACMA and organizer of the exhibition. -

Chapter 25 Baroque

CHAPTER 25 BAROQUE Flanders, Dutch Republic, France,,g & England Flanders After Marti n Luth er’ s Re forma tion the region of Flanders was divided. The Northern half became the Dutch Republic, present day Holland The southern half became Flanders, Belgium The Dutch Republic became Protestant and Flanders became Catholic The Dutch painted genre scenes and Flanders artists painted religious and mythol ogi ca l scenes Europe in the 17th Century 30 Years War (1618 – 1648) began as Catholics fighting Protestants, but shifted to secular, dynastic, and nationalistic concerns. Idea of united Christian Empire was abandoned for secu lar nation-states. Philip II’s (r. 1556 – 1598) repressive measures against Protestants led northern provinces to break from Spain and set up Dutch Republic. Southern Provinces remained under Spanish control and retained Catholicism as offiilfficial re liiligion. PlitildititiPolitical distinction btbetween HlldHolland an dBlid Belgium re fltthiflect this or iiigina l separation – religious and artistic differences. 25-2: Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, 1610-1611, oil on Cue Card canvas, 15 X 11. each wing 15 X 5 • Most sought a fter arti st of hi s time - Ambassador, diplomat, and court painter. •Paintinggy style •Sculptural qualities in figures •Dramatic chiaroscuro •Color and texture like the Venetians • Theatrical presentation like the Italian Baroque •Dynamic energy and unleashed passion of the Baroque •Triptych acts as one continuous space across the three panels. •Rubens studied Renaissance and Baroque works; made charcoal drawings of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and the Laocoon and his 2 sons. •Shortly after returning home , commissioned by Saint Walburga in Antwerp to paint altarpiece – Flemish churches affirmed their allegiance to Catholicism and Spanish Hapsburg role after Protestant iconoclasm in region. -

The Implementation of Chiaroscuro Visual Characters Using Woodcut Printmaking Technique on Textile

6th Bandung Creative Movement International Conference in Creative Industries 2019 (6th BCM 2019) The Implementation of Chiaroscuro Visual Characters Using Woodcut Printmaking Technique on Textile Mochammad Sigit Ramadhan1 1Craft Textile and Fashion, School of Creative Industries, Telkom University, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract One of the characteristics in the 15th century Renaissance that there was a dramatic visual expression in the worNs of art, especially painting. ,t‘s usually visualized Ey the artists at that time with the use of the light-dark principle on the objects presented in the artwork. This light-dark principle is known as chiaroscuro, and in the history of its development this chiaroscuro principle was applied also in printmaking by several artists in Europe. The chiaroscuro character can be built with the composition of color values with different intensities through the process of printing a matrix on the print media. There are two methods that can be used to produce color printmaking work, multi-block and reduction method that have their own advantages and disadvantages in visualizing the chiaroscuro principle. In addition to paper materials, the application of woodcut printmaking is also carried out on textile materials known as block-printing. However, there are not many works on textile materials that use the chiaroscuro principle because in general the coloring character in the visual image or design used tends to be solid color. Based on the explanation, there is an opportunity to apply the visual chiaro- scuro character to the textile materials by using woodcut printmaking technique. The use of woodcut printmaking technique allows artist to produce a number of different color values by referring to the light layer falling on the object, so that the impression of volume and depth created in the artwork will be more visible. -

A Demonstration of Painting in Oils in the Chiaroscuro

A DEMONSTRATION OF PAINTING IN OILS IN THE CHIAROSCURO (‘Light-dark’) METHOD by local award-winning artist KAY SPARKES Chiaroscuro (Italian for 'light-dark'), in art, is the use of strong contrasts between light and dark, usually bold contrasts affecting a whole composition. It is also a technical term used by artists and art historians for the use of contrasts of light to achieve a sense of volume in modelling three-dimensional objects and figures. Similar effects in cinema and photography also are called chiaroscuro. St. Peter in Prison The underlying principle is that solidity of form is best achieved by Rembrandt, 1631 by the light falling against it. Artists known for developing the technique include Leonardo Da Vinci, Caravaggio, Vermeer, Goya and Rembrandt. It is one of the modes for painting colour in Renaissance art. ABOUT KAY SPARKES Kay was born and grew up on the land near Gulgong, Central Western NSW. Music has always been a major part of her life. When she moved to Sydney she worked in the music industry Red Jug and Pears by and sang professionally. Kay Sparkes Kay moved to Maitland in 1996 where she began to explore her love of art and in 2006, friend and artist James Casey introduced her to canvas and oil and the use of the old master’s techniques – light and shadow ( the chiaroscuro technique). Kay loves painting and stuff we eat, touch and use everyday and those things become the subjects of her still life artworks. Kay has won many prizes including the Maitland Art Prize and Newcastle Art Prize. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St. -

Netherlands / ART the 10 Most Important Old Masters in Dutch

Netherlands / ART The 10 Most Important Old Masters in Dutch Painting by Samuel Spencer, CultureTrip.com https://theculturetrip.com/europe/the-netherlands/articles/the-10-most-important-old-masters- in-dutch-painting/ From stunning originals like Hieronymus Bosch through to the Dutch Golden Age of the 1650s, The Netherlands produced countless masterpieces across every category of painting. Most are familiar with towering figures like Rembrandt or Vermeer, but there is more to an art movement than two figures. From an internationally successful woman to Dürer’s great Dutch rival, the country has so much to offer art fans. Explore Holland with our guide to its best Old Masters. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) Perhaps the greatest and most famous portrait painter of all time, Rembrandt van Rijn was a master of observation, chiaroscuro and, perhaps most importantly, brutal honesty, as seen in his most famous works, the self-portraits. Critics and scholars disagree over how many he undertook, but whatever the actual number, it is a staggering collection including approximately 45 paintings, 30 etchings and seven drawings. These depict the ravages of time on the artist’s face without any sense of vanity, and are heartbreaking if seen in succession. His Biblical scenes and etchings are also superb, but it is those portraits that are his legacy. Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) Virtually ignored in his own time, Vermeer is now truly considered an Old Master. Like many from the Golden Age of Dutch Painting, Vermeer’s fascination was light, and the faithful and beautiful reproduction of it on canvas. This can best be seen on his most famous work Girl With a Pearl Earring, in which the interplay of light upon the various fabrics and the wonderful reflection shining on that pearl earring make it one of the masterpieces of western art. -

Art II: Masterpiece Monday

Visual Art Virtual Learning Art II: Masterpiece Monday May 4th, 2020 Lesson: 05-04-2020 Objective/Learning Target: I can reflect on the life and legacy of the famous artist Rembrandt van Rijn Explore a Take a closer technique or look at a Famous Artist happening Figure drawing Artist and their somewhere in the challenges work world right now! Masterpiece Technique What’s Up Thumbnail Figure Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Practice Skills Small, loose Known and new sketches of techniques objects we find or design concepts Rembrandt 1606-1669 Rembrandt is one of the most famous artists in history. Learn more about his life and work by viewing this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AkSymdjj2XU Defining Art Terms Baroque- this refers to a period of artistic style which flourished from the 1600’s to about 1750. Rembrandt’s work is associated with this style of work Chiaroscuro- method of arranging light and shadow in 2D art to create the illusion of 3D form. At times it is also referred to as modeling and shading (this technique was used widely by Baroque artists) Etching- a printmaking process in which the artist must engrave into a surface (often metal) to produce the desired image. The process begins by adding a layer of wax, the image is scratched away and acid is poured over the exposed metal which eats away the image which will be used to create the print Painter or Printmaker? How About Both! As an artist, or even simply and art student, have you ever had people ask you what is your favorite medium to work with? For many, it is easy to limit their answer to one mode of making art: drawing, painting, printmaking or ceramics… Rembrandt, maybe like you, enjoyed more than one and was well known for both his paintings and his etchings.