Rembrandt and the Dutch Catholics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

ICLIP & MAIL Tornadoes Rip Path of Death

PAGE SIXTEEN - EVENING HERALD. Tues.. April 10, 1978 Frank and Emaat EDUCATIONAL TV DINNERS T H f t Y ' P E *'epueArioN AL" i B c n u s B Police Malting Plans Panel Passes Measure Residents Not in Tune Caldwell Stops RSox, r- 1 IF y o u BAT O N E, For the Energy Crisis To Create Gaming Czar To Song of the Rails Jackson Sparks Yanks Page 3 Page 10 Y o u 'L l S e Page 12 Page 13 N B x r t i m b . Strv/CM O lltr td 31 S » n lc 0M OUtrad 31 Painting-Papering 32 Building Contracting 33 E X P E R T PAIN T IN G and INCOME TAX .) P. LEWIS & SON- Interior LEON CIESZYNSKI LANDSCAPING Specializlnf; and Exterior painting, paper BUILDER- New Homes. Ad THW/ti 4-10 Haudipfitpr PREPARATION in Exterior House Painting. hanging, rcmcxieling. carpen ditions. Remodeling. Rec Tree pruning, spraying, try. Fully insured 649-9658. Rooms. 'Garages, FHtchenq Fair Tonight, mowing, wcemng. Call 742- Remodeled. Ceilings. Bath Dogs-BIrdt-Pelt 43 Apaifmentt For Bant 53 Wanted to Bent 57 Autos For Sale 61 ftliSINESS A INDIVIDUAL 7947. ' PERSONAL Paperhanging Tile. Dormers, Roofing Sunny Thursday INCOiME TAXES For particular people, by Residential or Commercim, COCKER SPANIEL THREE BEDROOM USED GAR SPECULS Dick. Call 643-5703 anytime, 649-4291. PUPPIES - AKC Registered. DUPLEX- Stove, I’HEPAHKD - In the com- 1975 nyMOUTH D U tm Details on page 2 Inrl of your home or office, Have shots. Great Easter refrigerator, dishwasher. I'/z TEACHERS- Experienced baths. -

Rembrandt Self Portraits

Rembrandt Self Portraits Born to a family of millers in Leiden, Rembrandt left university at 14 to pursue a career as an artist. The decision turned out to be a good one since after serving his apprenticeship in Amsterdam he was singled out by Constantijn Huygens, the most influential patron in Holland. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh. In 1649, following Saskia's death from tuberculosis, Hendrickje Stoffels entered Rembrandt's household and six years later they had a son. Rembrandt's success in his early years was as a portrait painter to the rich denizens of Amsterdam at a time when the city was being transformed from a small nondescript port into the The Night Watch 1642 economic capital of the world. His Rembrandt painted the large painting The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq historical and religious paintings also between 1640 and 1642. This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The gave him wide acclaim. Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by the 18th century the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it Despite being known as a portrait painter was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a Rembrandt used his talent to push the gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. boundaries of painting. This direction made him unpopular in the later years of The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of his career as he shifted from being the the civic militia. -

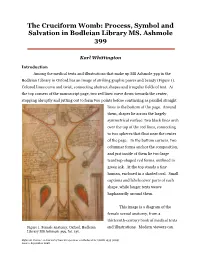

The Cruciform Womb: Process, Symbol and Salvation in Bodleian Library MS

The Cruciform Womb: Process, Symbol and Salvation in Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 399 Karl Whittington Introduction Among the medical texts and illustrations that make up MS Ashmole 399 in the Bodleian Library in Oxford lies an image of striking graphic power and beauty (Figure 1). Colored lines curve and twist, connecting abstract shapes and irregular fields of text. At the top corners of the manuscript page, two red lines curve down towards the center, stopping abruptly and jutting out to form two points before continuing as parallel straight lines to the bottom of the page. Around them, shapes lie across the largely symmetrical surface: two black lines arch over the top of the red lines, connecting to two spheres that float near the center of the page. In the bottom corners, two columnar forms anchor the composition, and just inside of them lie two large teardrop-shaped red forms, outlined in green ink. At the top stands a tiny human, enclosed in a shaded oval. Small captions and labels cover parts of each shape, while longer texts weave haphazardly around them. This image is a diagram of the female sexual anatomy, from a thirteenth-century book of medical texts Figure 1. Female anatomy, Oxford, Bodleian and illustrations. Modern viewers can Library MS Ashmole 399, fol. 13v. Different Visions: A Journal of New Perspectives on Medieval Art (ISSN 1935-5009) Issue 1, September 2008 Whittington– The Cruciform Womb: Process, Symbol and Salvation in Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 399 decipher easily only a few of these forms: to us, the drawing resembles some kind of map or abstract diagram more than a representation of actual anatomy, or anything else recognizable, for that matter. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3Rd Ed

Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Govaert Flinck” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/govaert- flinck/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Govaert Flinck Page 2 of 8 Govaert Flinck was born in the German city of Kleve, not far from the Dutch city of Nijmegen, on 25 January 1615. His merchant father, Teunis Govaertsz Flinck, was clearly prosperous, because in 1625 he was appointed steward of Kleve, a position reserved for men of stature.[1] That Flinck would become a painter was not apparent in his early years; in fact, according to Arnold Houbraken, the odds were against his pursuit of that interest. Teunis considered such a career unseemly and apprenticed his son to a cloth merchant. Flinck, however, never stopped drawing, and a fortunate incident changed his fate. According to Houbraken, “Lambert Jacobsz, [a] Mennonite, or Baptist teacher of Leeuwarden in Friesland, came to preach in Kleve and visit his fellow believers in the area.”[2] Lambert Jacobsz (ca. 1598–1636) was also a famous Mennonite painter, and he persuaded Flinck’s father that the artist’s profession was a respectable one. Around 1629, Govaert accompanied Lambert to Leeuwarden to train as a painter.[3] In Lambert’s workshop Flinck met the slightly older Jacob Adriaensz Backer (1608–51), with whom he became lifelong friends. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

The Exploration of Light As a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 8-7-1972 The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Vasko, Mary, "The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPLORATION OF LIGHT AS A MEANS OF EXPRESSION IN THE INTAGLIO PRINT MED I UH by Sister Mary Lucia Vasko, O.S.U. Candidate for the Master of Fine Arts in the College of Fine and Applied Arts of the Rochester Institute of Technology Submitted: August 7, 1372 Chief Advisor: Mr. Lawrence Williams TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . i i i INTRODUCTION v Thesis Proposal V Introduction to Research vi PART I THESIS RESEARCH Chapter 1. HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS AND BACKGROUND OF LIGHT AS AN ARTISTIC ELEMENT THE USE OF CHIAROSCURO BY EARLY ITALIAN AND GERMAN PRINTMAKERS INFLUENCE OF CARAVAGGIO ON DRAMATIC LIGHTING TECHNIQUE 12 REMBRANDT: MASTER OF LIGHT AND SHADOW 15 Light and Shadow in Landscape , 17 Psychological Illumination of Portraiture . , The Inner Light of Spirituality in Rembrandt's Works , 20 Light: Expressed Through Intaglio . Ik GOYA 27 DAUMIER . 35 0R0ZC0 33 PICASSO kl SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION OF RESEARCH hi PART I I THESIS PROJECT Chapter Page 1. -

I Speak As One in Doubt

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses August 2019 I Speak as One in Doubt Margaret Hazel Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Sculpture Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Margaret Hazel, "I Speak as One in Doubt" (2019). Masters Theses. 807. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/807 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Speak as One in Doubt. A Thesis Presented by Margaret Hazel Wilson Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2019 Department of Art I Speak as One in Doubt. A Thesis Presented by MARGARET HAZEL WILSON Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Chair _____________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member _____________________________ Robin Mandel, Member _____________________________ Sonja Drimmer, Member ______________________________ Young Min Moon, Graduate Program Director Department of Art ________________________________ Shona MacDonald, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION To my mom, who taught me to tell meandering stories, and that learning, and changing, is something to love. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer my heartfelt thanks to my committee members for their generous dialogue in the course of this thesis, especially my chair, Alexis Kuhr, for her excellent listening ear. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

Stowe: a Description of the Magnificent House and Gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Grenville Nugent Temple

www.e-rara.ch Stowe: a description of the magnificent house and gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Grenville Nugent Temple ... Seeley, Robert Benton Buckingham, 1780 ETH-Bibliothek Zürich Shelf Mark: Rar 6719 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-830 A Description of the House. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement.