The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3Rd Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black Chalk, with Traces of Red Chalk, and Framing Lines in Brown Ink

Jacob Adriaensz. BACKER (Harlingen 1608 - Amsterdam 1651) A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black chalk, with traces of red chalk, and framing lines in brown ink. Signed Backer. at the lower right. 168 x 182 mm. (6 5/8 x 7 1/8 in.) This charming drawing is a preparatory study for the pointing child at the extreme left of Jacob Backer’s Family Portrait with Christ Blessing the Children, a painting datable to c.1633-1634. This large canvas was unknown before its first appearance at auction in London in 1974, and is today in a private collection. The present sheet is drawn with a vivacity and a freedom in the application of the chalk that is stylistically indebted to Rembrandt’s chalk drawings of the same period, namely the early 1630s. Drawings executed in black chalk alone are rare in Backer’s oeuvre, but this drawing may be compared in particular to a signed and dated Self-Portrait in black chalk by Backer of 1638, in the Albertina in Vienna. A black chalk study of A Man in a Turban, in the Boijmans-van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, may also be likened to the present sheet. Provenance: Probably by descent to the artists’s brother, Tjerk Adriaensz. Backer, Amsterdam Iohan Quirijn van Regteren Altena, Amsterdam (his posthumous sale stamp [Lugt 4617] stamped on the backing sheet) Thence by descent. Literature: Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, Vol.I, New York, 1979, pp.20-21, no.3 (where dated to the mid-1630s), and also pp.46-47, under nos.16x and 17x, p.52, under no.19x and p.54, under no.20x; Werner Sumowksi, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, Landau/Pfalz, 1983, Vol.I, p.203, under no.72; Peter van den Brink, ‘Uitmuntend Schilder in het Groot: De schilder en tekenaar Jacob Adriansz. -

Betrachtungen Zur Sammlung

Valentina Vlasic Fokus Flinck Es ist fünfzig Jahre her, dass die letzte monographische Ausstellung den war, vorwegnahm – nämlich von seinem Freund, dem großen des barocken Malers Govert Flinck (1615-1660) stattgefunden hat. Wie niederländischen Nationaldichter Joost van den Vondel, mit dem „Reflecting History“ heute kam auch sie in seiner Geburtsstadt Kleve sagenumwobenen griechischen Künstler gleichgesetzt zu werden. zustande, und wurde vom Archivar und ersten Museumsleiter Fried- rich Gorissen (1912-1993) aus Anlass eines Jubiläums – damals des 350. Klever Sammlung Es ist ein großer Verdienst Friedrich Gorissens, Geburtstags von Flinck – organisiert. Sie fand im damaligen Städti- dass zahlreiche der historischen Besonderheiten Kleves für seine Fokus Flinck: Betrachtungen zur schen Museum Haus Koekkoek (heute Stiftung B.C. Koekkoek-Haus) Bürger und für die Nachwelt sichtbar sind. Mit seiner umsichti- statt, das 1957 gegründet und drei Jahre später eröffnet worden war. gen Forschungs- und Sammlungstätigkeit – u.a. den Werken nie- Sammlungsgeschichte, Die Ausstellung über Flinck war vom 4. Juli bis 26. September 1965 derrheinischer mittelalterlicher Bildschnitzer gewidmet, der Kunst zu sehen und es wurden – nicht unähnlich wie heute – 47 Gemälde des Barock am Klever Hof des Statthalters Johann Moritz von Nas- zum Werk und zur Ausstellung und 26 Zeichnungen aus aller Herren Länder präsentiert. Darunter sau-Siegen und der romantischen Klever Malerschule rund um Ba- befanden sich sowohl biblisch-mythologische Szenen wie Jakob er- rend Cornelis Koekkoek – legte er den Grundstein für das Klever hält Josephs blutigen Mantel (Kat. Nr. 22) und Salomo bittet um Weisheit Museum, das später von Guido de Werd umfassend ausgebaut wor- (Kat. Nr. 27) als auch Porträts wie Rembrandt als Hirte (Kat. -

History of the Current Understanding and Management of Tethered Spinal Cord

HISTORICAL VIGNETTE J Neurosurg Spine 25:78–87, 2016 History of the current understanding and management of tethered spinal cord Sam Safavi-Abbasi, MD, PhD,1 Timothy B. Mapstone, MD,2 Jacob B. Archer, MD,2 Christopher Wilson, MD,2 Nicholas Theodore, MD,1 Robert F. Spetzler, MD,1 and Mark C. Preul, MD1 1Department of Neurosurgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona; and 2Department of Neurosurgery, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma An understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of tethered cord syndrome (TCS) and modern management strate- gies have only developed within the past few decades. Current understanding of this entity first began with the under- standing and management of spina bifida; this later led to the gradual recognition of spina bifida occulta and the symp- toms associated with tethering of the filum terminale. In the 17th century, Dutch anatomists provided the first descriptions and initiated surgical management efforts for spina bifida. In the 19th century, the term “spina bifida occulta” was coined and various presentations of spinal dysraphism were appreciated. The association of urinary, cutaneous, and skeletal abnormalities with spinal dysraphism was recognized in the 20th century. Early in the 20th century, some physicians began to suspect that traction on the conus medullaris caused myelodysplasia-related symptoms and that prophylac- tic surgical management could prevent the occurrence of clinical manifestations. It was -

Rembrandt Self Portraits

Rembrandt Self Portraits Born to a family of millers in Leiden, Rembrandt left university at 14 to pursue a career as an artist. The decision turned out to be a good one since after serving his apprenticeship in Amsterdam he was singled out by Constantijn Huygens, the most influential patron in Holland. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh. In 1649, following Saskia's death from tuberculosis, Hendrickje Stoffels entered Rembrandt's household and six years later they had a son. Rembrandt's success in his early years was as a portrait painter to the rich denizens of Amsterdam at a time when the city was being transformed from a small nondescript port into the The Night Watch 1642 economic capital of the world. His Rembrandt painted the large painting The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq historical and religious paintings also between 1640 and 1642. This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The gave him wide acclaim. Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by the 18th century the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it Despite being known as a portrait painter was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a Rembrandt used his talent to push the gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. boundaries of painting. This direction made him unpopular in the later years of The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of his career as he shifted from being the the civic militia. -

Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape

Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a 1654 Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an oil on canvas Arcadian Landscape 139 x 170 cm signed and dated lower left: “G flinck. f. 1654 Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) (?)” GF-101 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape Page 2 of 11 How to cite Yeager-Crasselt, Lara. “Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape” (2018). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/elegant-shepherdess-listening-to-a- shepherd-playing-the-recorder-in-an-arcadian-landscape/ (accessed September 30, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape Page 3 of 11 Govaert Flinck’s depiction of an amorous shepherd and shepherdess in the Comparative Figures warm, evening light of a rolling landscape captures the lyrical character of the Dutch pastoral tradition.[1] The shepherd, dressed in a burnt umber robe, calf-high sandals, and a floppy brown hat, plays a recorder as he gazes longingly at the shepherdess seated beside him.[2] She returns her lover’s gaze with a coy, sideways glance, while placing a rose on her garland of flowers. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Major Rembrandt Portrait Painting on Loan to the Wadsworth from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Kim Hugo, (860) 838-4082 [email protected] Image file to accompany publicity of this announcement will be available for download at http://press.thewadsworth.org. Email to request login credentials. Major Rembrandt Portrait Painting on Loan to the Wadsworth from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Hartford, Conn. (January 21, 2020)—Rembrandt’s Titus in a Monk’s Habit (1660) is coming to Hartford, Connecticut. On loan from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the painting will be on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art from February 1 through April 30, 2020. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), recognized as one of the most important artists of his time and considered by many to be one of the greatest painters in European history, painted his teenage son in the guise of a monk at a crucial moment in his late career when he was revamping his business as a painter and recovering from bankruptcy. It has been fifty-three years since this painting has been on view in the United States making this a rare opportunity for visitors to experience a late portrait by the Dutch master among the collection of Baroque art at the Wadsworth renowned for its standout paintings by Rembrandt’s southern European contemporaries, Zurbarán, Oratio Gentileschi, and Caravaggio. While this painting has been infrequently seen in America, it exemplifies the dramatic use of light and dark to express human emotion for which Rembrandt’s late works are especially prized. “Titus in a Monk’s Habit is an important painting. It opens questions about the artist’s career, his use of traditional subjects, and the bold technique that has won him enduring fame,” says Oliver Tostmann, Susan Morse Hilles Curator of European Art at the Wadsworth. -

Adriaan Dortsman (1635–1682)

Adriaan Dortsman (1635–1682) uit de serie Belangrijke Amsterdamse Architecten door Anneke Huijser Adriaan Dortsman 1 ouwmeester Adriaan Dortsman of Dorsman (geboren rond 1635 in Vlissingen Adriaan Dortsman (1635-1682) en begraven 8 oktober 1682 in de Oosterkerk in Amsterdam) was in de zeven- Btiende eeuw een van de belangrijkste architecten die het Hollandse Classicis- me, met name de Nieuwe Stijl, in de bouwkunst introduceerden. Toch is hij wat onderbelicht gebleven ten opzichte van Jacob van Campen en Philips Vingboons. Dortsman kwam uit een geslacht van Vlissingse timmerlieden, leerde het vak van zijn vader, mogelijk Adriaen Adriaensz Dortsman, die in de Walstraat te Vlissingen woonde en in 1658 overleed. De doop- en familiegegevens zijn helaas bij een brand verloren gegaan. In elk geval had Adri- aan, zoals na zijn dood bleek, een broer, Anthony, en drie zusters, Jacomijntje, Elisabeth en Jannetie. Adriaan had grotere ambities dan in zijn familie gebruikelijk was. Hij vertrok in 1653 uit Vlissingen en studeerde o.a. landmeetkunde en vestingbouwkunde, waarschijnlijk in zijn woonplaats Haarlem of in Utrecht rond 1657, waar hij examen deed in landmeetkunde en aldaar zijn certificaat hiervoor behaalde. Hij volgde colleges wiskunde aan de Universiteit van Leiden rond 1658-59. De vroegst bekende tekening die Adriaan Dortsman, mogelijk al omstreeks 1658, in Leiden heeft gemaakt, wordt (volgens Wouter Kuyper in 1982) bewaard in het Leidse gemeente- archief. Het ontwerp is gesigneerd met ‘dortsman’, Het is een pentekening voorzien van arceringen en aquarel in licht grijsblauw. Het blijkt een voorloper te zijn voor zijn latere ont- werpen in Amsterdam. Ook bij de Rijksdienst voor Cultureel Erfgoed (RCE) in Amersfoort worden vroege tekeningen van Adriaan Dortsman bewaard, die helaas niet in de beeldbank van de dienst zijn opgenomen. -

Keyser, Thomas De Dutch, 1596 - 1667

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Keyser, Thomas de Dutch, 1596 - 1667 BIOGRAPHY Thomas de Keyser was the second son of Hendrick de Keyser (1565–1621), the famed Dutch architect, sculptor, and municipal stonemason of the city of Amsterdam, and his wife Beyken (Barbara) van Wildere, who hailed from Antwerp.[1] The family lived in a house that was part of the municipal stone yard along the Amstel River, between the Kloveniersburgwal and the Groenburgwal.[2] Thomas and his brothers Pieter and Willem were trained by their father in architecture, and each also became a highly regarded master stonemason and stone merchant in his own right. On January 10, 1616, the approximately 19-year-old Thomas became one of his father’s apprentices. As he must already have become proficient at the trade while growing up at the Amsterdam stone yard, the formal two-year apprenticeship that followed would have fulfilled the stonemasons’ guild requirements.[3] Thomas, however, achieved his greatest prominence as a painter and became the preeminent portraitist of Amsterdam’s burgeoning merchant class, at least until the arrival of Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606 - 1669) in 1632. Nothing is known about his artistic training as a painter, which likely occurred in his younger years. Four Amsterdam portraitists have been considered his possible teacher. Ann Jensen Adams, in her catalogue raisonné of Thomas de Keyser, posits (based on circumstantial evidence) that Cornelis van der Voort (c. 1576–1624) -

Jaarverslag 2008 (Pdf)

Jaarverslag 2008 inhoud 2 VAN PAULINE NAAR PAUL 8 PRESENTATIE 8 Tijdelijke tentoonstelling 14 Permanente tentoonstelling 20 EDUCATIE 34 COLLECTIE 52 ARCHEOLOGIE 54 MUSEUM WILLET -HOLTHUYSEN 58 INTERNATIONALE SAMENWERKING 62 Stichting Genootschap Amsterdams Historisch Museum 62 Het Genootschap Amsterdams Historisch Museum 65 Raad van Toezicht Stichting Amsterdams Historisch Museum 66 ANNUAL REPORT SUMMARY 68 DAG LIEVE PAULINE 74 BIJLAGEN 74 Bezoekersaantallen Van Pauline naar Paul Interview met scheidende directeur Per 1 januari 2009 is Paul Spies directeur van het Amsterdams Historisch Pauline Kruseman en komende Museum. De opvolger van Pauline Kruseman was hiervoor mededirecteur directeur Paul Spies door Teio van het Kunsthistorisch Advies- en Organisatiebureau d’arts, dat hij zelf Meedendorp. meer dan 20 jaar geleden met twee kompanen oprichtte. Aan het eind van 2008 keken Pauline en Paul gezamenlijk naar hun respectievelijk verleden en toekomende tijd in het Amsterdams Historisch Museum. Voordat Pauline ongeveer 18 jaar geleden het voormalige Burgerweeshuis binnentrok, werkte zij als zakelijk leider voor het kit/Tropenmuseum (20 jaar). Pauline: ‘Terugkijkend moet ik zeggen dat ik heb gewerkt voor de twee mooiste cultuurhistorische musea in Amsterdam. Ik heb heel bewust voor het werken in een cultuurhistorisch museum gekozen en voor het openbaar kunstbezit, daar heeft altijd mijn belangstelling gelegen. Ik vond het fantastisch om hier voor een mooie, eeuwenoude collectie te mogen zorgen en die in te zetten voor allerlei presentaties, om verhalen te vertellen over Amsterdam en de Amsterdammers. Mijn hart – en dat weet iedereen – ligt heel erg bij educatie. Het klinkt misschien heel ouderwets, maar ik ben erg voor l’éducation permanente. Of het Favoriete tentoonstellingen of aankopen tijdens haar directoraat wil ze nu voor kinderen of voor volwassenen is, hier kun je prachtige verhalen liever niet noemen, alle projecten zijn haar om diverse redenen even lief. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

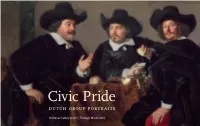

NGA | Civic Pride Group Portraits from Amsterdam

fig. 4 Arent Coster the early stages of the Dutch revolt against (silversmith), Drinking Horn of the Harquebus- Spanish rule (1568 – 1648), the guardsmen iers’ Guild, 1547, buffalo could even be deployed at the front lines, horn mounted on silver pedestal, Rijksmuseum, leading one contemporary observer to Amsterdam, on loan from call them “the muscles and nerves” of the the City of Amsterdam. Dutch Republic. Paintings of governors of civic insti- tutions, such as those by Flinck and Van der Helst, contain fewer figures than do militia group portraits, but they are no less visually compelling or historically signifi- cant. It was only through the efforts of such citizens and organizations that the young Dutch Republic achieved its economic, political, and artistic golden age in the sev- enteenth century. The numerous portraits Harquebusiers’ ceremonial drinking horn room with a platter of fresh oysters is likely of these remarkable people, painted by to the governors. The vessel, a buffalo horn to be Geertruyd Nachtglas, the adminis- important artists, allow us to look back at supported by a rich silver mount in the trator of the Kloveniersdoelen, who had that world and envision the character and form of a stylized tree with a rampant lion assumed that position in 1654 following the appearance of those who were instrumen- and dragon (fig. 4), had been fashioned in death of her father Jacob (seen holding the tal in creating such a dynamic and success- 1547 and was displayed at important events. drinking horn in Flinck’s work). Because ful society. The Harquebusiers’ emblem, a griffin’s the Great Hall was already fully decorated, claw, appears on a gilded shield on the Van der Helst’s painting was installed over This exhibition was organized by the National wall.