Elegant Shepherdess Listening to a Shepherd Playing the Recorder in an Arcadian Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black Chalk, with Traces of Red Chalk, and Framing Lines in Brown Ink

Jacob Adriaensz. BACKER (Harlingen 1608 - Amsterdam 1651) A Young Boy in a Plumed Cap Black chalk, with traces of red chalk, and framing lines in brown ink. Signed Backer. at the lower right. 168 x 182 mm. (6 5/8 x 7 1/8 in.) This charming drawing is a preparatory study for the pointing child at the extreme left of Jacob Backer’s Family Portrait with Christ Blessing the Children, a painting datable to c.1633-1634. This large canvas was unknown before its first appearance at auction in London in 1974, and is today in a private collection. The present sheet is drawn with a vivacity and a freedom in the application of the chalk that is stylistically indebted to Rembrandt’s chalk drawings of the same period, namely the early 1630s. Drawings executed in black chalk alone are rare in Backer’s oeuvre, but this drawing may be compared in particular to a signed and dated Self-Portrait in black chalk by Backer of 1638, in the Albertina in Vienna. A black chalk study of A Man in a Turban, in the Boijmans-van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, may also be likened to the present sheet. Provenance: Probably by descent to the artists’s brother, Tjerk Adriaensz. Backer, Amsterdam Iohan Quirijn van Regteren Altena, Amsterdam (his posthumous sale stamp [Lugt 4617] stamped on the backing sheet) Thence by descent. Literature: Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt School, Vol.I, New York, 1979, pp.20-21, no.3 (where dated to the mid-1630s), and also pp.46-47, under nos.16x and 17x, p.52, under no.19x and p.54, under no.20x; Werner Sumowksi, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, Landau/Pfalz, 1983, Vol.I, p.203, under no.72; Peter van den Brink, ‘Uitmuntend Schilder in het Groot: De schilder en tekenaar Jacob Adriansz. -

Betrachtungen Zur Sammlung

Valentina Vlasic Fokus Flinck Es ist fünfzig Jahre her, dass die letzte monographische Ausstellung den war, vorwegnahm – nämlich von seinem Freund, dem großen des barocken Malers Govert Flinck (1615-1660) stattgefunden hat. Wie niederländischen Nationaldichter Joost van den Vondel, mit dem „Reflecting History“ heute kam auch sie in seiner Geburtsstadt Kleve sagenumwobenen griechischen Künstler gleichgesetzt zu werden. zustande, und wurde vom Archivar und ersten Museumsleiter Fried- rich Gorissen (1912-1993) aus Anlass eines Jubiläums – damals des 350. Klever Sammlung Es ist ein großer Verdienst Friedrich Gorissens, Geburtstags von Flinck – organisiert. Sie fand im damaligen Städti- dass zahlreiche der historischen Besonderheiten Kleves für seine Fokus Flinck: Betrachtungen zur schen Museum Haus Koekkoek (heute Stiftung B.C. Koekkoek-Haus) Bürger und für die Nachwelt sichtbar sind. Mit seiner umsichti- statt, das 1957 gegründet und drei Jahre später eröffnet worden war. gen Forschungs- und Sammlungstätigkeit – u.a. den Werken nie- Sammlungsgeschichte, Die Ausstellung über Flinck war vom 4. Juli bis 26. September 1965 derrheinischer mittelalterlicher Bildschnitzer gewidmet, der Kunst zu sehen und es wurden – nicht unähnlich wie heute – 47 Gemälde des Barock am Klever Hof des Statthalters Johann Moritz von Nas- zum Werk und zur Ausstellung und 26 Zeichnungen aus aller Herren Länder präsentiert. Darunter sau-Siegen und der romantischen Klever Malerschule rund um Ba- befanden sich sowohl biblisch-mythologische Szenen wie Jakob er- rend Cornelis Koekkoek – legte er den Grundstein für das Klever hält Josephs blutigen Mantel (Kat. Nr. 22) und Salomo bittet um Weisheit Museum, das später von Guido de Werd umfassend ausgebaut wor- (Kat. Nr. 27) als auch Porträts wie Rembrandt als Hirte (Kat. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3Rd Ed

Govaert Flinck (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Govaert Flinck” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/govaert- flinck/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Govaert Flinck Page 2 of 8 Govaert Flinck was born in the German city of Kleve, not far from the Dutch city of Nijmegen, on 25 January 1615. His merchant father, Teunis Govaertsz Flinck, was clearly prosperous, because in 1625 he was appointed steward of Kleve, a position reserved for men of stature.[1] That Flinck would become a painter was not apparent in his early years; in fact, according to Arnold Houbraken, the odds were against his pursuit of that interest. Teunis considered such a career unseemly and apprenticed his son to a cloth merchant. Flinck, however, never stopped drawing, and a fortunate incident changed his fate. According to Houbraken, “Lambert Jacobsz, [a] Mennonite, or Baptist teacher of Leeuwarden in Friesland, came to preach in Kleve and visit his fellow believers in the area.”[2] Lambert Jacobsz (ca. 1598–1636) was also a famous Mennonite painter, and he persuaded Flinck’s father that the artist’s profession was a respectable one. Around 1629, Govaert accompanied Lambert to Leeuwarden to train as a painter.[3] In Lambert’s workshop Flinck met the slightly older Jacob Adriaensz Backer (1608–51), with whom he became lifelong friends. -

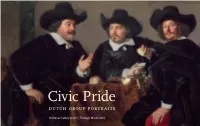

NGA | Civic Pride Group Portraits from Amsterdam

fig. 4 Arent Coster the early stages of the Dutch revolt against (silversmith), Drinking Horn of the Harquebus- Spanish rule (1568 – 1648), the guardsmen iers’ Guild, 1547, buffalo could even be deployed at the front lines, horn mounted on silver pedestal, Rijksmuseum, leading one contemporary observer to Amsterdam, on loan from call them “the muscles and nerves” of the the City of Amsterdam. Dutch Republic. Paintings of governors of civic insti- tutions, such as those by Flinck and Van der Helst, contain fewer figures than do militia group portraits, but they are no less visually compelling or historically signifi- cant. It was only through the efforts of such citizens and organizations that the young Dutch Republic achieved its economic, political, and artistic golden age in the sev- enteenth century. The numerous portraits Harquebusiers’ ceremonial drinking horn room with a platter of fresh oysters is likely of these remarkable people, painted by to the governors. The vessel, a buffalo horn to be Geertruyd Nachtglas, the adminis- important artists, allow us to look back at supported by a rich silver mount in the trator of the Kloveniersdoelen, who had that world and envision the character and form of a stylized tree with a rampant lion assumed that position in 1654 following the appearance of those who were instrumen- and dragon (fig. 4), had been fashioned in death of her father Jacob (seen holding the tal in creating such a dynamic and success- 1547 and was displayed at important events. drinking horn in Flinck’s work). Because ful society. The Harquebusiers’ emblem, a griffin’s the Great Hall was already fully decorated, claw, appears on a gilded shield on the Van der Helst’s painting was installed over This exhibition was organized by the National wall. -

Govert Flinck – Reflecting History’ with an Artistic Intervention by Ori Gersht, Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Cleves / Germany (04/10/2015 – 17/01/2016)

Exhibition ‘Govert Flinck – Reflecting History’ with an artistic intervention by Ori Gersht, Museum Kurhaus Kleve, Cleves / Germany (04/10/2015 – 17/01/2016) The exhibition Govert Flinck – Reflecting History will be shown at the Museum Kurhaus Kleve – Ewald Mataré-Collection from the 4th of October 2015 until the 17th of January 2016. His four hundredth birthday in 2015 provides the occasion for the Museum Kurhaus Kleve to show a comprehensive solo exhibition that will represent the first retrospective in more than fifty years. Govert Flinck (1615-1660), was one of the most prominent portraitists during the Golden Age of Dutch painting and became one of the most celebrated painters of his time in Amsterdam. Even today he is regarded as one of Rembrandt’s most gifted pupils. Already during his lifetime, his fame had by far exceeded that of his teacher. For the Cleves exhibition, precious works on loan from all over the world are expected. 30 paintings and an equal amount of drawings and prints are to illuminate the career of Govert Flinck, his proximity to and dependence on Rembrandt, as well as his development into an artistically independent, successful painter. Both the rich diversity in his oeuvre as well as the high quality of his portraits and historical paintings are made visible. Prints based on his paintings and poetry written about his works give insight into the contemporary reception of his art. Govert Flinck was born on the 25th of January of the year 1615 in Cleves, as son to a well-respected textile trader. In his early youth he moved to Leeuwarden and shortly after to Amsterdam for an education in the art of painting. -

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague, Netherlands HNA CONFERENCE 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague 2-4 June 2022 Program committee: Stijn Bussels, Leiden University (chair) Edwin Buijsen, Mauritshuis Suzanne Laemers, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History Judith Noorman, University of Amsterdam Gabri van Tussenbroek, University of Amsterdam | City of Amsterdam Abbie Vandivere, Mauritshuis and University of Amsterdam KEYNOTE LECTURES ClauDia Swan, Washington University A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic 1 The global baroque world was a world of goods. Transoceanic trade routes compounded travel over land for commercial gain, and the distribution of wares took on global dimensions. Precious metals, spices, textiles, and, later, slaves were among the myriad commodities transported from west to east and in some cases back again. Taste followed trade—or so the story tends to be told. This lecture addresses the traffic in global goods in the Dutch world from a different perspective—piracy. “A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic” will present and explore exemplary narratives of piracy and their impact and, more broadly, the contingencies of consumption and taste- making as the result of politically charged violence. Inspired by recent scholarship on ships, shipping, maritime pictures, and piracy this lecture offers a new lens onto the culture of piracy as well as the material goods obtained by piracy, and how their capture informed new patterns of consumption in the Dutch Republic. Jan Blanc, University of Geneva Dutch Seventeenth Century or Dutch Golden Age? Words, concepts and ideology Historians of seventeenth-century Dutch art have long been accustomed to studying not only works of art and artists, but also archives and textual sources. -

Prints by 1639, Etching, 200 X 164 Mm, Lucas Van Leyden (1494–1533) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Among British Museum, London, Malcolm Collection, Inv

© 2021 The Leiden Collection Self-Portrait Page 2 of 12 Self-Portrait 1643 oil on panel Govaert Flinck 73.1 x 53.5 cm (Kleve 1615 – 1660 Amsterdam) signed and dated in brown paint along left side of narrow horizontally oriented lower plank: “G.flinck.f.1643” GF-103 How to cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. “Self-Portrait” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/self- portrait-2/ (accessed September 24, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Self-Portrait Page 3 of 12 With a posture and expression that exude status and youthful self- Comparative Figures confidence, Govaert Flinck painted himself in 1643, at age twenty-eight, facing slightly to the right with his right arm leaning on a brown ledge and his eyes directed straight at the viewer. He wears a gold-trimmed velvet mantle over a low-cut jerkin, and a white, high-collared vest whose frilled edges are visible below his neck and at his wrist. His shoulder-length, ginger-colored hair flows out from under his velvet beret. Around his neck, partially Fig 1. Detail of Govaert concealed by his mantle, hangs a chain. Flinck, GF-103, showing the brocade and collar Flinck’s assuredness of execution is comparable to that of his appearance. -

A Fugitive's Success Story Jacob Van Loo in Paris

BRILL_NKJ63_BW_NKJ_63 08-07-14 10:15 Pagina 302 BRILL_NKJ63_BW_NKJ_63 08-07-14 10:15 Pagina 303 303 A fugitive’s success story Jacob van Loo in Paris (1661-1670) Judith Noorman A conviction for homicide forced the Amsterdam painter Jacob van Loo (1614-1670) to flee the Dutch Republic. In 1661, he permanently moved to Paris, where he lived until his death in 1670. Despite his criminal past, Van Loo continued to be socially and professionally successful in Paris, adjusting his production to suit a Parisian market predominantly focused on portraiture. At the same time, he continued to work for the Dutch elite while expanding his clientele to include wealthy and important French patrons. In 1663, he became a member of the Académie Royale, an institution that appears to have been particularly hostile towards foreign artists; Van Loo’s admission took a lengthy thirteen months due to extra requirements, but his official acceptance into the profession enhanced his social status and his studio consequently became something of a social meeting place. Perhaps the ultimate testament to Van Loo’s successful integration into Parisian society, however, was the so-called Van Loo painters’ dynasty; Van Loo’s descendants came to dominate eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French painting.1 Van Loo was not a typical immigrant artist. A wealth of documentation and the unquestionable permanency of Van Loo’s immigration set him apart from others. Because of the manslaughter conviction, he knew he could never return to his home country. While other immigrant artists who were abroad for shorter periods of time could afford failure, Van Loo’s success was paramount not just for his own survival, but also for the future of his children, who followed their father into exile. -

4 O C T Ob E R 2 015 to 17 Ja N U Ar Y 2

»GOVERT FLINCK 4 October 2015 to 17 January 2016 REFLECTING Museum Kurhaus Kleve – Ewald Mataré-Collection, HISTORY« Kleve / Germany ork Y ew N ollection, C eiden L he T 1643, , Self-portrait , GOVERT FLINCK of Kloveniers’ civic guards in Amsterdam. Today’s most well- most Today’s Amsterdam. in guards civic Kloveniers’ of have survived. have into present-day modes of perception. of modes present-day into A portraits for the Great Hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the seat seat the Kloveniersdoelen, the of Hall Great the for portraits the fi rst works by Flinck with his signature signature his with Flinck by works rst fi the 1636 in Starting fascinating still-lifes of Juan Sanchez Cotàn, translating them them translating Cotàn, Sanchez Juan of still-lifes fascinating mong other works, Govert Flinck painted two of seven group group seven of two painted Flinck Govert works, other mong missions is not known. not is missions structure of historical painting in previous projects, such as the the as such projects, previous in painting historical of structure Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Rijksmuseum teacher, or whether his teacher voluntarily let him have com- have him let voluntarily teacher his whether or teacher, years, has already critically engaged with the aesthetics and and aesthetics the with engaged critically already has years, Rembrandt as shepherd as Rembrandt 1636 , , FLINCK GOVERT painting. Whether Flinck took business away from his former former his from away business took Flinck Whether painting. The artist Ori Gersht, who has been living in London for many many for London in living been has who Gersht, Ori artist The MAIN WORKS WORKS MAIN Rembrandt’s competitors, especially in the area of portrait portrait of area the in especially competitors, Rembrandt’s the essence of artistic freedom, juxtaposing his own position to it. -

The Amsterdam Civic Guard Portraits Within and Outside the New Rijksmuseum, Pt

Volume 5, Issue 1 (Winter 2013) The Amsterdam Civic Guard Portraits within and outside the New Rijksmuseum, Pt. I D.C. Meijer Jr. (Tom van der Molen, translator) Recommended Citation: D. C. Meijer Jr., “The Amsterdam Civic Guard Portraits within and outside the New Rijksmuseum Pt. I,” trans. Tom van der Molen, JHNA 5:1 (Winter 2013) DOI:10.5092/jhna.2013.5.1.5 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/amsterdam-civic-guard-portraits-within-outside-new-ri- jksmuseum-part-i/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 5:1 (Winter 2013) 1 THE AMSTERDAM CIVIC GUARD PORTRAITS WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE NEW RIJKSMUSEUM, PT. I D.C. Meijer Jr. (Tom van der Molen, translator) 1 lmost one-and-a-half years ago, we stood at the grave of A. D. de Vries Az.,1 the tireless fighter for truth and beauty, the scholarly friend of the arts, for whom a lie was a horror, in whichever form or for whatever goal. His incorruptible diligence, alongside his excep- Ational memory and his sharp analytic skills, made him an art historian of the first rank. When- ever these extraordinary gifts were employed together with his restless diligence and enduring patience, made this son of one of Amsterdam’s most influential art-loving families easily triumph over all kinds of small difficulties. -

Revealing a Painter's Secrets Govert Flinck's Isaac Blessing

A world first: revealing a painter’s secrets Govert Flinck’s Isaac blessing Jacob unravelled Research on the painting Isaac blessing Jacob by Govert Flinck (1615-1660), which was carried out as part of the project ‘The use of materials and painting techniques of Rembrandt’s pupils’, was recently completed. For once, the findings are not being published in a scholarly article but are being presented to the public in a different, unique way. Never before could the working method of a celebrated painter from the Dutch Golden Age be followed so closely. Flinck, a pupil of Rembrandt’s, has the world’s first. Special software has been developed to add underlying layers of paint and technical information to the painting itself. You can explore Flinck’s techniques yourself, and become a virtual partner in his creative process, which dates from hundreds of years ago. These AR application is made by the Augmented Reality Lab (AR Lab) of the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague commissioned by the National Service for Cultural Heritage (RCE) and is a product of the research Agenda 2009-2012 of the RCE. The AR application originated from a cooperation between the RCE and Museum Catharijneconvent. The research of Isaac blesses Jacob took place in the context of the project ‘The use of materials and painting techniques of Rembrandt’s pupils’: a collaborative project under the guidance of Margriet van Eikema Hommes between the RCE, the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and the University of Amsterdam. Museum Catharijneconvent invites you to the opening of the iPad presentation ‘Govert Flinck’s Isaac blessing Jacob unravelled’ on Thursday 16 May in Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht. -

Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck Datasheet

Image not found or type unknown TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +1 212 645 1111 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/us Published 6th Nov 2017 Image not found or type unknown Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck New Research Edited by Stephanie S. Dickey ISBN 9789462582224 Publisher WBooks Binding Paperback / softback Territory USA & Canada Size 9.06 in x 11.02 in Pages 272 Pages Illustrations 100 color, 100 b&w Price $47.50 New Research concerning Rembrandt's rivals: Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck Sixteen essays exploring the work of two of 17th-century Amsterdam's most ambitious painters, Govert Flinck and Ferdinand Bol Accompanies the first ever exhibition on Flinck and Bol, to be held at The Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam from October 2017 to February 2018 This book presents sixteen essays exploring the work of two of 17th-century Amsterdam's most ambitious painters, Govert Flinckand Ferdinand Bol. Museum curators, academic art historians, and conservation scientists from six different countries come together to investigate form, content, and context from a variety of perspectives. Eric Jan Slujter examines how changing patterns of patronage contributed to both artists' stylistic evolution. Hilbert Lootsma traces the rise and fall of their critical fortunes from their own time until today. Ann Jensen Adams situates their work in the shifting market for portraiture. Jasper Hillegers explores the origins of Flinck's career in the Leeuwarden studio of Lambert Jacobsz. Other authors present contextual and technical analyzes of individual paintings. Portrait identities are revealed, painterly tricks uncovered, and both artists are shown to be influential teachers and members of an intellectual community in which art and theater were closely linked.