Rembrandt's Three Crosses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING in SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00

A Q U A T I N T : P R I N T I N G I N S H A D E S GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY 74 Heath Street Hampstead Village London NW3 1DN AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING IN SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00 GILDENSARTS.COM [email protected] +44 (0)20 7435 3340 G I L D E N ’ S A R T S G A L L E R Y GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES April – June 2015 Director: Ofer Gildor Text and Concept: Daniela Boi and Veronica Czeisler Gallery Assistant: Costanza Sciascia Design: Steve Hayes AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES In its ongoing goal to research and promote works on paper and the art of printmaking, Gilden’s Arts Gallery is glad to present its new exhibition Aquatint: Printing in Shades. Aquatint was first invented in 1650 by the printmaker Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) in Amsterdam. The technique was soon forgotten until the 18th century, when a French artist, Jean Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781), rediscovers a way of achieving tone on a copper plate without the hard labour involved in mezzotint. It was however not in France but in England where this technique spread and flourished. Paul Sandby (1731 - 1809) refined the technique and coined the term Aquatint to describe the medium’s capacity to create the effects of ink and colour washes. He and other British artists used Aquatint to capture the pictorial quality and tonal complexities of watercolour and painting. -

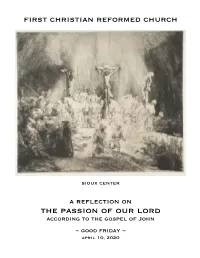

2020 Good Friday Order of Service

first christian reformed church sioux center a reflection on the passion of our lord according to the gospel of John ~ good friday ~ april 10, 2020 order of service Prelude ~ “Were you There” Linker “O Sacred Head” Burkhardt Welcome Call to Worship Today we remember Jesus was crucified. He was pierced for our transgressions. He suffered and died for our iniquities. We remember the sacrifice of our Lord with gratitude because his death gives us life and brings redemption to the world. Let us worship our Savior. Prayer of Invocation O God, who for our redemption gave your only Son to the death of the cross, and by his glorious resurrection delivered us from the power of our enemy: grant us so to die daily to sin, that we may evermore live with him in the joy of his resurrection, now and forever. Prayers of Intercession and Illumination Hymn: “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence,” verses 1-3 Hymn continued on the next page. Scripture Reading: John 18.1-14 ~ Jesus’ Arrest and Betrayal Hymn: “Meekness and Majesty” ~ Lif Up Your Hearts 157, verses 1-3 Verse 1: Verse 2: Meekness and majesty, manhood and Deity Father's pure radiance, perfect in innocence, in perfect harmony, the Man who is God. yet learns obedience to death on a cross, Lord of eternity dwells in humanity, suffering to give us life, conquering through sacrifice, kneels in humility, and washes our feet. and, as they crucify, prays, “Father forgive.” Chorus: Chorus Oh, what a mystery—meekness and majesty; bow down and worship, for this is your God. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

A Catalogue of Rembrandt's Etchings

Fk-.oVO, UU«xH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofrembrOOhind a' catalogue of rembrandt's etchings CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED AND COMPLETELY ILLUSTRATED B y ARTHUR M. HIND OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM SLADE PROFESSOR OF FINE ART IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I INTRODUCTION AND CATALOGUE WITH FRONTISPIECE IN PHOTOGRAVURE, AND TEN PLATES ILLUSTRATING STUDIES FOR THE ETCHINGS METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON First Published February igis Second Edition, revised and in part rewritten . '9^3 THE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUWG UIN/IVERSIT^ PROVO, UTAH PREFACE THE present catalogue is a revised edition of the one which appeared in 1912 in my Rembrandt's Etchings, an Essay and a Catalogue, with some Notes on the Drawings. The Introduction is also composed to a large extent of material from the same volume, but revised and re-arranged with the definite object of providing such notes as would be of most use to the student and collector of Rembrandt's etchings (e.g. in the addition of a list of values). The volume of plates, to which a few subjects have been added since 1912, will no doubt be of service for purposes of identifica- tion, and will, I hope, appeal equally to the amateur or artist who merely wishes to be reminded of this incomparable series of subjects. For drawing my attention to new states or other details of description in the Catalogue, I would express acknowledgment to Jhr. Mr. J. F. -

Private Collection of Camille Pissarro Works Featured in Swann Galleries’ Old Master-Modern Sale

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Alexandra Nelson October 14, 2016 Communications Director 212-254-4710 ext. 19 [email protected] Private Collection of Camille Pissarro Works Featured in Swann Galleries’ Old Master-Modern Sale New York— On Thursday, November 3, Swann Galleries will hold an auction of Old Master Through Modern Prints, featuring section of the sale devoted to a collection works by Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Icon. The beginning of the auction offers works by renowned Old Masters, with impressive runs by Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt van Rijn. Scarce engravings by Dürer include his 1514 Melencholia I, a well-inked impression estimated at $70,000 to $100,000, and Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513 ($60,000 to $90,000), as well as a very scarce chiaroscuro woodcut of Ulrich Varnbüler, 1522 ($40,000 to $60,000). Rembrandt’s etching, engraving and drypoint Christ before Pilate: Large Plate, 1635-36, is estimated at $60,000 to $90,000, while one of earliest known impressions of Cottages Beside a Canal: A View of Diemen, circa 1645, is expected to sell for $50,000 to $80,000. The highlight of the sale is a private collection of prints and drawings by Impressionist master Camille Pissarro. This standalone catalogue surveys Impressionism’s most prolific printmaker, and comprises 67 lots of prints and drawings, including many lifetime impressions that have rarely been seen at auction. One of these is Femme vidant une brouette, 1880, a scarce etching and drypoint of which fewer than thirty exist. Only three other lifetime impressions have appeared at auction; this one is expected to sell for $30,000 to $50,000. -

Remembering Rembrandt

For Immediate Release 13 February 2006 Contact: Hannah Schmidt 020.7389.2964 [email protected] Remembering Rembrandt ... CHRISTIE’S CELEBRATES REMBRANDT’S 400TH ANNIVERSARY Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints Wednesday, 29 March 2006 Christie’s London London – On July 15, 1606, one of the world’s most versatile, innovative, and influential artists Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669) was born in Leiden. Four hundred years later, Christie’s joins the celebrations of the anniversary of the master’s birth. An important group of fifty-five etchings by the artist from the collection of Dutch industrialist and patron, G.A.H. Buisman Jzn. will be offered alongside the 29 March sale of Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints in London. “This superb private collection lends a fascinating insight into the technique and mastery of the artist’s graphic oeuvre and with estimates starting at just £1,500 offers an excellent opportunity to collect an original by this famous artist in his 400th anniversary year,” said Richard Lloyd, Head of Christie’s Print Department. Rembrandt was a multi-talented artist, acquiring international fame not only as painter and draughtsman but also for his graphic works. He explored different forms, styles and subjects throughout his artistic life, with his first etching dating to circa 1626 and his last from 1665. The strength of his reputation as one of the most important graphic artists remains to this day. The collection to be sold at Christie’s reflects the broad range of subjects that Rembrandt addressed from portraits, and self-portraits, to landscapes, allegorical scenes, mythological and biblical stories as well as animal studies. -

Printmaking Through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012

Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Printmaking as Art 6 Glossary of Printing Terms 7 A Brief History of Printmaking Written by Jennifer Jensen 10 Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap , Rembrandt Written by Hailey Leek 11 Lesson Plan for Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap Written by Virginia Catherall 14 Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo, Hokusai Written by Jennifer Jensen 16 Lesson Plan for Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo Written by Jennifer Jensen 20 Lambing , Leighton Written by Kathryn Dennett 21 Lesson Plan for Lambing Written by Kathryn Dennett 32 Madame Louison, Rouault Written by Tiya Karaus 35 Lesson Plan for Madame Louison Written by Tiya Karaus 41 Prodigal Son , Benton Written by Joanna Walden 42 Lesson Plan for Prodigal Son Written by Joanna Walden 47 Flotsam, Gottlieb Written by Joanna Walden 48 Lesson Plan for Flotsam Written by Joanna Walden 55 Fourth of July Still Life, Flack Written by Susan Price 57 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 59 Reverberations, Katz Written by Jennie LaFortune 60 Lesson Plan for Reverberations Written by Jennie LaFortune Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership and the Professional Outreach Programs in the Schools (POPS) through the Utah State Office of Education 1 Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Image List 1. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669), Dutch Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap with Plume , 1638 Etching Gift of Merrilee and Howard Douglas Clark 1996.47.1 2. -

DRYPOINT-WOODCUT Always Loved Those Images, and I Wanted to a Certain Amount of Unpredictability Learn from Cassatt’S Process,” Heck Says

that use the symbol of the heart to explore ideas of love and emotion. A somewhat similar approach is taken in the recent Printmaking series “Fascinators,” in which Heck adorns A passion for printmaking unites these four accomplished artists, who her young subjects with headpieces shaped like Möbius strips. each work with a different process. Heck’s work combines two traditional printmaking processes: drypoint, an intaglio process, and woodcut, a relief process. In BY AUSTIN R. WILLIAMS intaglio processes—such as engraving, etch- ing and drypoint—marks are carved into a Printmaking is drawing’s first cousin. In both metal plate using one of several methods. disciplines artists work directly with their hands Those indentations are filled with ink, and to create lines and tones, ultimately resulting in a when the plate is pressed to paper, the ink is finished work on paper. But printmaking involves transferred to the paper. In relief processes, an additional array of tools and techniques that have such as woodcut and linocut, the opposite occurs. In these methods the artist carves fascinated artists for centuries. Every printmaking process offers its own sort of beauty while also away the negative parts of the image and ink imposing certain constraints on the artist. Here we TODAY is applied to the remaining, raised portions explore the work of four printmakers, who share their of the plate, which is then pressed to paper. thoughts on their chosen printmaking processes. Heck was inspired to combine intaglio and relief processes by Mary Cassatt (1844– 1926), who in the late 1800s produced color ELLEN HECK: etchings inspired by Japanese woodcuts that had recently been exhibited in Paris. -

Rembrandt. the New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings

BR.OCT.pg.proof.corrs_Layout 1 16/09/2014 11:55 Page 675 massive undertaking and the broadest and brief sketch to a finished piece but more often Books most detailed survey of the artist’s prints to merely adjusted the shading or removed date, comprising seven volumes (two text, excess background lines. It is clear that some three of plates, and two with plates of copies). of the reworkings of his early plates were The authors of the New Hollstein took full carried out by others in the studio, among advantage of the array of technological them the Leiden printmaker Jan van Vliet, advances available to present-day scholars – known for having reproduced some of the relative facility of travel and the ability to Rembrandt’s paintings in print. Several produce high-quality digital images of prints anonymous printmakers appear to have also and X-radiographs of watermarks. They had a hand in reworking light sketches Rembrandt. The New Hollstein looked at works together and apart, sharing produced by the master around 1630 and Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings large digital images that revealed changes dif- 1631. The authors were able to perceive these and Woodcuts 1450–1700. By Erik ficult if not impossible to identify with the underlying sketches thanks to enlarged digital Hinterding and Jaco Rutgers. 7 vols. 2,210 naked eye or a magnifying glass. details; such prints, extensively re-etched pp. incl. numerous col. + b. & w. ills. Their methods and findings are described in by another hand, are identified by a ‘w’ for (Sound and Vision Publishers, Ouderkerk the introduction to the first volume. -

Catalogue of the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of Engravings, Etchings, Woodcuts of the Xv and Xvi Centuries

CATALOGUE OF THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL EXHIBITION OF ENGRAVINGS, ETCHINGS, WOODCUTS OF THE XV AND XVI CENTURIES MARCH 3RD TO MARCH 2IST, 1936 M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY, INC. 14 EAST FIFTY-SEVENTH STREET NEW YORK ILLUSTRATED BOOKS AND NEWSPAPERS Discourse was deemed Man's noblest attribute, And written words the glory of his hand; Then followed Printing with enlarged command For thought — dominion vast and absolute For spreading truth, and making love expand. Now prose and verse sun\ into disrepute Must lacquey a dumb Art that best can suit The taste of this once-intellectual hand. A backward movement surely have we here, From manhood — bac\ to childhood; for the age — Bac\ towards caverned life's first rude career. U Avaunt this vile abuse of pictured page. Must eyes be all in all, the tongue and ear Nothing? Heaven keep us from a lower stage. WILLIAM WORDSWORTH ARTISTS REPRESENTED IN THIS EXHIBITION GERMANY ANONYMOUS (1425-1450) DOTTED PRINT 5 MASTER E. S 6 MARTIN SCHONGAUER 7 ANONYMOUS NORTH GERMAN (About 1480) 9 MASTER B. G 10 SCHOOL OF MARTIN SCHONGAUER 10 ISRAHEL VAN MECKENEM 10 MASTER M Z 13 AUGUSTIN HIRSCHVOGEL 14 HANS SEBALD LAUTENSACK 14 HANS BURGKMAIR 15 JOHANN ULRICH WECHTLIN (Pilgrim) 15 LUCAS CRANACH r6 NETHERLANDS MASTER F VB (F. van Brugge?) j$ LUCAS VAN LEYDEN Xo DIRICK JACOBSZOON VELLERT 21 ITALY NIELLO PRINT (Attributed to Francesco Francia) ....... 22 ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE: THE SIBYLS 22 CRISTOFANO ROBETTA 2, ANONYMOUS NORTH ITALIAN: "THE TAROCCHI CARDS" 24 DOMENICO BECCAFUMI (Master H-E) 2K ANONYMOUS XVI CENTURY: ROMAN SCHOOL 25 ANDREA MANTEGNA . _- -*5 SCHOOL OF ANDREA MANTEGNA 26 BARTOLOMEO DA BRESCIA 27 NICOLETTO ROSEX DA MODENA 28 JACOPO DE' BARBARI ...