Of All Rembrandt's Etchings. the Hundred Guilder Print (Fig. 4.1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

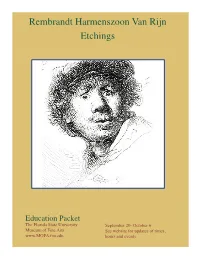

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

A Catalogue of Rembrandt's Etchings

Fk-.oVO, UU«xH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofrembrOOhind a' catalogue of rembrandt's etchings CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED AND COMPLETELY ILLUSTRATED B y ARTHUR M. HIND OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM SLADE PROFESSOR OF FINE ART IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I INTRODUCTION AND CATALOGUE WITH FRONTISPIECE IN PHOTOGRAVURE, AND TEN PLATES ILLUSTRATING STUDIES FOR THE ETCHINGS METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON First Published February igis Second Edition, revised and in part rewritten . '9^3 THE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUWG UIN/IVERSIT^ PROVO, UTAH PREFACE THE present catalogue is a revised edition of the one which appeared in 1912 in my Rembrandt's Etchings, an Essay and a Catalogue, with some Notes on the Drawings. The Introduction is also composed to a large extent of material from the same volume, but revised and re-arranged with the definite object of providing such notes as would be of most use to the student and collector of Rembrandt's etchings (e.g. in the addition of a list of values). The volume of plates, to which a few subjects have been added since 1912, will no doubt be of service for purposes of identifica- tion, and will, I hope, appeal equally to the amateur or artist who merely wishes to be reminded of this incomparable series of subjects. For drawing my attention to new states or other details of description in the Catalogue, I would express acknowledgment to Jhr. Mr. J. F. -

Remembering Rembrandt

For Immediate Release 13 February 2006 Contact: Hannah Schmidt 020.7389.2964 [email protected] Remembering Rembrandt ... CHRISTIE’S CELEBRATES REMBRANDT’S 400TH ANNIVERSARY Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints Wednesday, 29 March 2006 Christie’s London London – On July 15, 1606, one of the world’s most versatile, innovative, and influential artists Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669) was born in Leiden. Four hundred years later, Christie’s joins the celebrations of the anniversary of the master’s birth. An important group of fifty-five etchings by the artist from the collection of Dutch industrialist and patron, G.A.H. Buisman Jzn. will be offered alongside the 29 March sale of Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints in London. “This superb private collection lends a fascinating insight into the technique and mastery of the artist’s graphic oeuvre and with estimates starting at just £1,500 offers an excellent opportunity to collect an original by this famous artist in his 400th anniversary year,” said Richard Lloyd, Head of Christie’s Print Department. Rembrandt was a multi-talented artist, acquiring international fame not only as painter and draughtsman but also for his graphic works. He explored different forms, styles and subjects throughout his artistic life, with his first etching dating to circa 1626 and his last from 1665. The strength of his reputation as one of the most important graphic artists remains to this day. The collection to be sold at Christie’s reflects the broad range of subjects that Rembrandt addressed from portraits, and self-portraits, to landscapes, allegorical scenes, mythological and biblical stories as well as animal studies. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

Rembrandt's Three Crosses

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Spotlight Series: October 2008 By Paul Crenshaw, assistant curator for prints and drawings and senior lecturer in art history One of the most dynamic prints ever made, Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Three Crosses (1653) displays technical innovation and engagement with the human subjectivity of Rembrandt van Rijn The Three Crosses, 1653 Drypoint (4th state), 15 1/4 x 17 13/16" Christ’s death. A torrential downpour of lines Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 envelopes dozens of figures on the hill of Rembrandt van Rijn Golgotha, where Christ is pictured crucified The Three Crosses, 1660-61 Etching and drypoint (4th state)tate) amidst the two thieves. Even though it is an 15 1/4 x 17 13/16 " Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 inherently tragic subject commonly portrayed in Christian tradition, never before had it been staged with such sweeping emotional force. Rembrandt was inspired by the text of the Gospels (Matthew 27:45–54) proclaiming that a darkness covered the land from noon to three o’clock, when Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Elí, Elí, lemá sabachtháni?” (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). When Jesus died, the passage continues, the earth shook, rocks split, tombs opened, and the bodies of many sleeping saints arose. To achieve these supernatural effects, Rembrandt employed the kind of bold technical ingenuity that helped define him as one of the most significant printmakers of his age. The Kemper Art Museum impression is a fine example of the fourth state of the print, which gives a dramatically different tenor and narrative focus to his subject than earlier states did. -

The Light of Descartes in Rembrandts's Mature Self-Portraits

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-03-19 The Light of Descartes in Rembrandts's Mature Self-Portraits Melanie Kathleen Allred Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Allred, Melanie Kathleen, "The Light of Descartes in Rembrandts's Mature Self-Portraits" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8109. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Light of Descartes in Rembrandt’s Mature Self-Portraits Melanie Kathleen Allred A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Martha Moffitt Peacock, Chair Elliott D. Wise James Russel Swensen Department of Comparative Arts and Letters Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Melanie Kathleen Allred All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Light of Descartes in Rembrandt’s Mature Self-Portraits Melanie Kathleen Allred Department of Comparative Arts and Letters, BYU Master of Arts Rembrandt’s use of light in his self-portraits has received an abundance of scholarly attention throughout the centuries—and for good reason. His light delights the eye and captivates the mind with its textural quality and dramatic presence. At a time of scientific inquiry and religious reformation that was reshaping the way individuals understood themselves and their relationship to God, Rembrandt’s light may carry more intellectual significance than has previously been thought. -

November 2009 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 26, No. 2 www.hnanews.org November 2009 Willem van Haecht, Apelles Painting Campaspe, c. 1630. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague. On view at the Rubenshuis, Antwerp, November 28, 2009 – February 28, 2010. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents HNA News ............................................................................1 Board Members Obituary.................................................................................. 2 Personalia ............................................................................... 3 Ann Jensen Adams Exhibitions ............................................................................ 4 Dagmar Eichberger Exhibition Review .................................................................8 Wayne Franits Matt Kavaler Museum News ..................................................................... -

November 2014 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 31, No. 2 November 2014 Jacob Jordaens, Merry Company, c. 1644. Watercolor over black chalk, heightened with white gouache, 21.9 x 23.8 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Exhibited at The Getty Center, Los Angeles, October 14, 2014 – January 11, 2015. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – Dawn Odell Lewis and Clark College 0615 SW Palatine Hill Road Portland OR 97219-7899 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 HNA News ............................................................................1 Lloyd DeWitt (2012-2016) Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) Personalia ............................................................................... 4 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Boston Conference Photos ....................................................5 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Exhibitions ......................................................................... -

The Woman at Christ's Feet in Rembrandt's Hundred

BEYOND MATTHEW 19: THE WOMAN AT CHRIST’S FEET IN REMBRANDT’S HUNDRED GUILDER PRINT Paul Crenshaw This study proposes that our understanding of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print has been limited by seeing it exclusively as illustrating the narrative vignettes related in the gospel passage of Matthew 19. Rather than being inspired only by this single textual source—as undeniably rich as it is—Rembrandt drew broadly on other representations, both biblical and nonscriptural, as visual inspiration for various figures and the overall compositional devices in the print. In particular, the reclining figure reaching up to touch the hem of Christ’s cloak is identified as the woman with the issue of blood, found elsewhere in the gospel passages. As a small portion of a larger study, the identification serves to point to a wider understanding of the print as a path to salvation through faith, and a mode of art production and viewing that is associative rather than merely illustrative. DOI: 10.18277/makf.2015.04 he persistence of the nickname of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print is remarkable. In large part this is due to the “shock factor” of a high price tag, and even though in the absence of comparative prices or costs of living, the worth of a hundred guilders in Rembrandt’s time is relatively unclear to most people today, it nonetheless Tseems like a lot of money. Thus the price/title bond acts as a powerful carrier of value. Unfortunately, it is not a designation that promotes any discernment or understanding of the events depicted in the scene, as is traditionally expected of most titles of works of art. -

Catalogue of an Exhibition of Etchings by Rembrandt 1606-1669 : March

rlV I 66 o CATALOGUE OF AN EXHIBITION OF ETCHINGS BY REMBRANDT 1606-1669 MARCH-APRIL 1925 M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY 14 EAST FIFTY-SEVENTH STREET NEW YORK D. B. UPDIKE, THE MERRYMOONT PRESS, BOSTON REMBRANDT VAN RIJN (1606-1669) HE opinion amongst etchers which enthrones TRembrandt as the king of their craft is the most recent instance of perfect unanimity amongst people of all nationalities. As we all say that Phidias was the great est sculptor, Homer the greatest epic poet, and Shake speare the greatest dramatist, so we are all agreed upon the world-wide supremacy of Rembrandt. In his own lines of work there is no one in all history to be compared to Rembrandt; in artistic influence he has one equal, entirely unlike himself, and that is Ra phael. They are the two most influential graphic artists of all time. P. G. HAMERTON: "The Etchings of Rembrandt," pp. 13-14. In the whole history of art Rembrandt stands out as one of the solitary and unapproachable personalities who have struck their own style, and stamped their influence, for good or for bad, on posterity. In his etched work his unique position is realized to even greater ad vantage than in painting; for in the latter sphere Frans Hals, his senior by a few years, was not far behind in brilliance of brush and incisive delineation. But among contemporary etchers there was no one who combined the same mastery of medium with a tithe of his sig nificance of expression. In fact, no worthy rival in this field can be found before the last century, and then in whom but Whistler? But in the range of his genius Rembrandt still stands alone. -

Early Reception of Rembrandt's Hundred Guilder Print: Jan Steen's

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Early Reception of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print: Jan Steen’s Emulation Amy Golahny [email protected] Recommended Citation: Amy Golahny, “Early Reception of Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print: Jan Steen’s Emulation,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.10 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/early-reception-rembrandt-hundred-guil- der-print-jan-steen-emulation/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 EARLY RECEPTION OF REMBRANDT’S HUNDRED GUILDER PRINT: JAN STEEN’S EMULATION Amy Golahny Among the earliest visual responses to Rembrandt’s master print is Jan Steen’s Village Wedding of 1653. In it, Steen transformed somber and ill figures from the Hundred Guilder Print into raucously playful, joking, or drunk participants in the farce of a marriage ritual. In transforming the serious biblical subject into a comic village wedding, Steen departed from the general reverential regard for the print and demonstrated his respectful rivalry with Rembrandt. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.10 Fig. 1 Rembrandt, Hundred Guilder Print, ca. 1649, etching, engraving, and drypoint on European paper, second state of two, 28 x 39.3 cm (plate). New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs.