Early Reception of Rembrandt's Hundred Guilder Print: Jan Steen's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

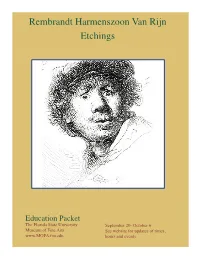

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

A Catalogue of Rembrandt's Etchings

Fk-.oVO, UU«xH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofrembrOOhind a' catalogue of rembrandt's etchings CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED AND COMPLETELY ILLUSTRATED B y ARTHUR M. HIND OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM SLADE PROFESSOR OF FINE ART IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I INTRODUCTION AND CATALOGUE WITH FRONTISPIECE IN PHOTOGRAVURE, AND TEN PLATES ILLUSTRATING STUDIES FOR THE ETCHINGS METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON First Published February igis Second Edition, revised and in part rewritten . '9^3 THE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUWG UIN/IVERSIT^ PROVO, UTAH PREFACE THE present catalogue is a revised edition of the one which appeared in 1912 in my Rembrandt's Etchings, an Essay and a Catalogue, with some Notes on the Drawings. The Introduction is also composed to a large extent of material from the same volume, but revised and re-arranged with the definite object of providing such notes as would be of most use to the student and collector of Rembrandt's etchings (e.g. in the addition of a list of values). The volume of plates, to which a few subjects have been added since 1912, will no doubt be of service for purposes of identifica- tion, and will, I hope, appeal equally to the amateur or artist who merely wishes to be reminded of this incomparable series of subjects. For drawing my attention to new states or other details of description in the Catalogue, I would express acknowledgment to Jhr. Mr. J. F. -

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam)

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Gabriel Metsu” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/gabriel- metsu/ (accessed September 28, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Gabriel Metsu Page 2 of 5 Gabriel Metsu was born sometime in late 1629. His parents were the painter Jacques Metsu (ca. 1588–1629) and the midwife Jacquemijn Garniers (ca. 1590–1651).[1] Before settling in Leiden around 1615, Metsu’s father spent some time in Gouda, earning his living as a painter of patterns for tapestry manufacturers. No work by Jacques is known, nor do paintings attributed to him appear in Leiden inventories.[2] Both of Metsu’s parents came from Southwest Flanders, but when they were still children their families moved to the Dutch Republic. When the couple wed in Leiden in 1625, neither was young and both had previously been married. Jacquemijn’s second husband, Guilliam Fermout (d. ca. 1624) from Dordrecht, had also been a painter. Jacques Metsu never knew his son, for he died eight months before Metsu was born.[3] In 1636 his widow took a fourth husband, Cornelis Bontecraey (d. 1649), an inland water skipper with sufficient means to provide well for Metsu, as well as for his half-brother and two half-sisters—all three from Jacquemijn’s first marriage. -

Remembering Rembrandt

For Immediate Release 13 February 2006 Contact: Hannah Schmidt 020.7389.2964 [email protected] Remembering Rembrandt ... CHRISTIE’S CELEBRATES REMBRANDT’S 400TH ANNIVERSARY Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints Wednesday, 29 March 2006 Christie’s London London – On July 15, 1606, one of the world’s most versatile, innovative, and influential artists Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669) was born in Leiden. Four hundred years later, Christie’s joins the celebrations of the anniversary of the master’s birth. An important group of fifty-five etchings by the artist from the collection of Dutch industrialist and patron, G.A.H. Buisman Jzn. will be offered alongside the 29 March sale of Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints in London. “This superb private collection lends a fascinating insight into the technique and mastery of the artist’s graphic oeuvre and with estimates starting at just £1,500 offers an excellent opportunity to collect an original by this famous artist in his 400th anniversary year,” said Richard Lloyd, Head of Christie’s Print Department. Rembrandt was a multi-talented artist, acquiring international fame not only as painter and draughtsman but also for his graphic works. He explored different forms, styles and subjects throughout his artistic life, with his first etching dating to circa 1626 and his last from 1665. The strength of his reputation as one of the most important graphic artists remains to this day. The collection to be sold at Christie’s reflects the broad range of subjects that Rembrandt addressed from portraits, and self-portraits, to landscapes, allegorical scenes, mythological and biblical stories as well as animal studies. -

The Five Senses in Genre Paintings of the Dutch Golden Age

The Five Senses in Genre Paintings of the Dutch Golden Age Kitsirin Kitisakon+ (Thailand) Abstract This article aims to study one of the most popular themes in 17th-Century Dutch genre paintings - the five senses - in its forms and religious interpretations. Firstly, while two means of representation were used to clearly illustrate the subject, some genre scenes could also be read on a subtle level; this effectively means that such five senses images can be interpreted somewhere between clarity and am- biguity. Secondly, three distinct religious meanings were identified in these genre paintings. Vanity was associated with the theme because the pursuit of pleasure is futile, while sin was believed to be committed via sensory organs. As for the Parable of the Prodigal Son, party scenes alluding to the five senses can be read as relating to the episode of the son having spent all his fortune. Keywords: Five Senses, Genre Painting, Dutch Golden Age, Prodigal Son + Dr. Kitsirin Kitisakon, Lecturer, Visual Arts Dept., Faculty of Fine and Applied Art, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. The Five Senses… | 125 Introduction In the 16th and 17th Centuries, the five senses had never been more popular as subject matter for graphic art, especially in the Low Countries. Since Nordenfalk (1985), this theme has been occasionally discussed in monographs, catalogues of specific artists, or Dutch genre painting studies. Yet, an analysis of the modes of representation of the five senses seems to have been ignored, and there is a certain lack of fresh interest in their religious interpretations. From this observa- tion, this article aims to firstly examine how the five senses were represented in the Dutch genre paintings of the Golden Age, inspect how artists narrated them; secondly, reinvestigate how they can be religiously interpreted and propose deeper meanings which go beyond realistic appearance. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

Dutch Art, 17Th Century

Dutch Art, 17th century The Dutch Golden Age was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the 17th century, in which Dutch trade, science, military, and art were among the most acclaimed in the world. The first section is characterized by the Thirty Years' War, which ended in 1648. The Golden Age continued in peacetime during the Dutch Republic until the end of the century. The transition by the Netherlands to the foremost maritime and economic power in the world has been called the "Dutch Miracle" by historian K. W. Swart. Adriaen van Ostade (1610 – 1685) was a Dutch Golden Age painter of genre works. He and his brother were pupils of Frans Hals and like him, spent most of their lives in Haarlem. A01 The Painter in his Workshop 1633 A02 Resting Travelers 1671 David Teniers the Younger (1610 – 1690) was a Flemish painter, printmaker, draughtsman, miniaturist painter, staffage painter, copyist and art curator. He was an extremely versatile artist known for his prolific output. He was an innovator in a wide range of genres such as history, genre, landscape, portrait and still life. He is now best remembered as the leading Flemish genre painter of his day. Teniers is particularly known for developing the peasant genre, the tavern scene, pictures of collections and scenes with alchemists and physicians. A03 Peasant Wedding 1650 A04 Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his gallery in Brussels Gerrit Dou (1613 – 1675), also known as Gerard and Douw or Dow, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, whose small, highly polished paintings are typical of the Leiden fijnschilders. -

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry Wednesday, November 8, 2017 the Exhibition Is Organized by the 4:30 – 7:30 P.M

vermeer and the masters of genre painting national gallery of art october 22, 2017 – january 21, 2018 AMONG THE MOST ENDURING IM AGES of the Dutch Golden Age are genre paintings, or scenes of daily life, from the third quarter of the seventeenth century. Made during a time of unparalleled inno- vation and prosperity, these exquisite portrayals of refined Dutch society — elegant men and women writing letters, playing music, and tending to their daily rituals — present a genteel world that is extraordinarily appealing. Today, Johannes Vermeer is the most cel- ebrated of these painters thanks to the beauty and tranquility of his images. Yet other masters, among them Gerard ter Borch, Gerrit Dou, Frans van Mieris, and Gabriel Metsu, also created works that are remarkably similar in style, subject matter, and technique. The visual connections between these artists’ paintings suggest a robust atmosphere of innovation and exchange — but to what extent did they inspire each other’s work, and to what extent did they follow their own artistic evolution? This exhibition brings together almost seventy paintings made between about 1655 and 1680 to explore these questions and celebrate the inspiration, rivalry, and artistic evolution of Vermeer and other masters of genre painting. Cover Johannes Vermeer Lady Writing (detail), c. 1665 oil on canvas National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Harry Waldron Havemeyer and Horace Havemeyer, Jr., in memory of their father, Horace Havemeyer (cat. 2.3) (opposite) detail fig. 7 Gabriel Metsu Man Writing a Letter Fig. 1 (left) Gerard ter Borch Woman Writing a Letter, c. 1655 – 1656 oil on panel Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague (cat. -

Prints by Such Artists As Cornelis Cort After Frans Floris (1561) and Jan Saenredam After Hendrick Goltzius (Ca

© 2021 The Leiden Collection Self-Portrait with a Lute: Sense of Hearing Page 2 of 9 Self-Portrait with a Lute: Sense of ca. 1664 Hearing oil on canvas 23.8 x 19.3 cm Jan Steen signed in dark paint, lower right (Leiden 1626 – 1679 Leiden) corner: “JSteen” (“JS” in ligature) JS-115 How to cite Kloek, Wouter. “Self-Portrait with a Lute: Sense of Hearing” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/self-portrait-with-a-lute-sense-of-hearing/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Self-Portrait with a Lute: Sense of Hearing Page 3 of 9 In this painting Jan Steen has portrayed himself dressed informally, laughing, Comparative Figures and playing the lute. He wears a large gray coat, with ample room for his shirt sleeves, and red leggings. A songbook, to which he pays no attention, lies on a table at the left, which is the only piece of furniture to be seen. Although this small self-portrait is difficult to date, it is probable that Steen executed it in Haarlem around 1664. The definition of the face is comparable to that of the fool in The Rhetoricians in Brussels, which dates from the same period.[1] A comparison between the Leiden Collection painting and Self-Portrait Playing the Lute in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid (fig 1), painted around 1666–68, reveals two striking differences.[2] First, in the Fig 1. -

Rembrandt's Three Crosses

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Spotlight Series: October 2008 By Paul Crenshaw, assistant curator for prints and drawings and senior lecturer in art history One of the most dynamic prints ever made, Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Three Crosses (1653) displays technical innovation and engagement with the human subjectivity of Rembrandt van Rijn The Three Crosses, 1653 Drypoint (4th state), 15 1/4 x 17 13/16" Christ’s death. A torrential downpour of lines Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 envelopes dozens of figures on the hill of Rembrandt van Rijn Golgotha, where Christ is pictured crucified The Three Crosses, 1660-61 Etching and drypoint (4th state)tate) amidst the two thieves. Even though it is an 15 1/4 x 17 13/16 " Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 inherently tragic subject commonly portrayed in Christian tradition, never before had it been staged with such sweeping emotional force. Rembrandt was inspired by the text of the Gospels (Matthew 27:45–54) proclaiming that a darkness covered the land from noon to three o’clock, when Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Elí, Elí, lemá sabachtháni?” (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). When Jesus died, the passage continues, the earth shook, rocks split, tombs opened, and the bodies of many sleeping saints arose. To achieve these supernatural effects, Rembrandt employed the kind of bold technical ingenuity that helped define him as one of the most significant printmakers of his age. The Kemper Art Museum impression is a fine example of the fourth state of the print, which gives a dramatically different tenor and narrative focus to his subject than earlier states did. -

Jan Steen: the Drawing Lesson

Jan Steen THE DRAWING LESSON Jan Steen THE DRAWING LESSON John Walsh GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES For my teacher Julius S. Held in gratitude Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Jan Steen (Dutch, 1626-1679). The Drawing Lesson, circa 1665 (detail). Oil on panel, Mollie Holtman, Editor 49.3 x 41 cm. (i93/s x i6î/4 in.). Los Angeles, Stacy Miyagawa, Production Coordinator J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PB.388). Jeffrey Cohen, Designer Lou Meluso, Photographer Frontispiece: Jan Steen. Self-Portrait, circa 1665. © 1996 The J. Paul Getty Museum Oil on canvas, 73 x 62 cm (283/4 x 243/ in.). 17985 Pacific Coast Highway 8 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (sK-A-383). Malibu, California 90265-5799 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs Mailing address: provided) courtesy of the owners unless other- P.O. BOX 2112 wise indicated. Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Library of Congress Austin, Texas Cataloging-in-Publication Data Printed by Typecraft, Inc., Pasadena, California Walsh, John, 1937- Bound by Roswell Bookbinding, Phoenix, Jan Steen : the Drawing lesson / John Walsh, Arizona p. cm.—(Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographic references. ISBN 0-89326-392-4 1. Steen, Jan, 1626-1679 Drawing lesson. 2. Steen, Jan, 1626-1679—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series. ND653.S8A64 1996 759.9492—dc20 96-3913 CIP CONTENTS Introduction i A Familiar Face 5 Picturing the Workshop 27 The Training of a Painter 43 Another Look Around 61 Notes on the Literature 78 Acknowledgments 88 Final page folds out, providing a reference color plate of The Drawing Lesson INTRODUCTION In a spacious vaulted room a painter leans over to correct a drawing by one of his two pupils, a young boy and a beautifully dressed girl, who look on [FIGURE i and FOLDOUT].