72. Dutch Baroque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 • Fourth Sunday After Pentecost

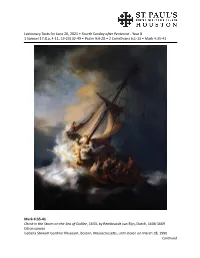

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 •Fourth Sunday after Pentecost- Year B 1 Samuel 17:(1a, 4-11, 19-23) 32-49 • Psalm 9:9-20 • 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 • Mark 4:35-41 Mark 4:35-41 Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633, by Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669 Oil on canvas Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, until stolen on March 18, 1990 Continued Lectionary Texts for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost• June 20, 2021 • Page 2 In his only painted seascape, Rembrandt dramatically portrays the continuing battle of nature against human frailty, both physical and spiritual. The frightened and overwhelmed disciples struggle to retain control of their fishing boat as huge waves crash over the bow. One disciple is hanging over the side of the boat vomiting. A sail is torn, rope lines are flying loose, disaster is imminent as rocks appear in the left foreground. The dark clouds, the wind, the waves combine to create the terror of the painting and the terror of the disciples. Nature’s upheaval is the cause of, as well as a metaphor for, the fear that grips the disciples. The emotional turbulence is magni- fied by the dramatic impact of the painting, approximately 4’ wide by 5’ high. Jesus, whose face is lightened in the group on the right, remains calm. He woke up and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Peace! Be still!” Then the wind ceased, and there was a dead calm, and he asked the disciples, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” The face of a 13th disciple looks directly out at the viewer in the horizontal center of the painting. -

The Novel As Dutch Painting

one The Novel as Dutch Painting In a memorable review of Jane Austen’s Emma (1816), Walter Scott cele brated the novelist for her faithful representation of the familiar and the commonplace. Austen had, according to Scott, helped to perfect what was fundamentally a new kind of fiction: “the art of copying from nature as she really exists in the common walks of life.” Rather than “the splendid scenes of an imaginary world,” her novels presented the reader with “a correct and striking representation of that which [was] daily taking place around him.” Scott’s warm welcome of Emma has long been known to literary historians and fans of Austen alike. But what is less often remarked is the analogy to visual art with which he drove home the argument. In vividly conjuring up the “common incidents” of daily life, Austen’s novels also recalled for him “something of the merits of the Flemish school of painting. The subjects are not often elegant and certainly never grand; but they are finished up to nature, and with a precision which delights the reader.”1 Just what Flemish paintings did Scott have in mind? If it is hard to see much resemblance between an Austen novel and a van Eyck altarpiece or a mythological image by Rubens, it is not much easier to recognize the world of Emma in the tavern scenes and village festivals that constitute the typical subjects of an artist like David Teniers the Younger (figs. 1-1 and 1-2). Scott’s repeated insistence on the “ordinary” and the “common” in Austen’s art—as when he welcomes her scrupulous adherence to “common inci dents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks of life,” or de scribes her narratives as “composed of such common occurrences as may have fallen under the observation of most folks”—strongly suggests that it is seventeenth-century genre painting of which he was thinking; and Teniers was by far the best known Flemish painter of such images.2 (He had in fact figured prominently in the first Old Master exhibit of Dutch and 1 2 chapter one Figure 1-1. -

REPRODUCTION in the Summer of 1695, Johann Wilhelm, Elector

CHAPTER EIGHT REPRODUCTION In the summer of 1695, Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine, visited Frederik Ruysch’s museum, where he undoubtedly saw paintings by Ruysch’s daughters, particularly those done by Rachel. At this time Rachel had just given birth to her first child, but motherhood had not prevented her from continuing her career as a painter. Her sister Anna had given up painting when she married, but Rachel had carried on, and could meanwhile demand high prices for her flower still lifes. In 1699 her success was formally recognized when she became the first woman elected to membership in Pictura, the painters’ confraternity in The Hague. In 1656 the Hague painters had withdrawn from the Guild of St Luke, having been prompted to do so by ‘arrogance’, according to their former guild-brothers, who included the house-painters and decora- tors. The new society was limited to ‘artist-painters’, sculptors, engrav- ers and a few art lovers. According to the new confraternity’s rules and regulations, the guildhall was to be decorated with the members’ own paintings. On 4 June 1701, the painter Jurriaan Pool presented the confraternity with a flower piece by his wife, Rachel Ruysch. Painters often gave a work on loan, but this painting was donated to Pictura, and a subsequent inventory of its possessions listed ‘an especially fine flower painting by Miss Rachel Ruysch’.1 Rachel Many of Rachel Ruysch’s clients were wealthy. The high prices she charged them enabled her to concentrate on only a few pieces a year, each of which took several months to complete. -

* Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to Enlightenment

Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to enlightenment: European art and culture 1665-1765 Jan van Huysum: the rise and strange demise of the baroque flower piece Richard Beresford 21 / 22 March 2012 Introduction: At his death in 1749 Jan van Huysum was celebrated as the greatest of all flower painters. His biographer Jan van Gool stated that Van Huysum had ‘soared beyond all his predecessors and out of sight’. The pastellist Jean-Etienne Liotard regarded him as having perfected the oil painter’s art. Such was contemporary appreciation of his works that it is thought he was the best paid of any painter in Europe in the 18th century. Van Huysum’s reputation, however, was soon to decline. The Van Eyckian perfection of his technique would be dismissed by a generation learning to appreciate the aesthetic of impressionism. His artistic standing was then blighted by the onset of modernist taste. The 1920s and 30s saw his works removed from public display in public galleries, including both the Rijksmuseum and the Mauritshuis. The critic Just Havelaar was not the only one who wanted to ‘sweep all that flowery rubbish into the garbage’. Echoes of the same sentiment survive even today. It was not until 2006 that the artist received his first serious re-evaluation in the form of a major retrospective exhibition. If we wish to appreciate Van Huysum it is no good looking at his work through the filter an early 20th-century aesthetic prejudice. The purpose of this lecture is to place the artist’s achievement in its true cultural and artistic context. -

DUTCH and ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850

DUTCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850 The art and ship models in this station are devoted to the early Dutch and English seascape painters. The historical emphasis here explains the importance of the sea to these nations. Historical Overview: The Dutch: During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as one of the great maritime oriented empires. The Dutch Republic was born in 1579 with the signing of the Union of Utrecht by the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Two years later the United Provinces of the Netherlands declared their independence from the Spain. They formed a loose confederation as a representative body that met in The Hague where they decided on issues of taxation and defense. During their heyday, the Dutch enjoyed a worldwide empire, dominated international trade and built the strongest economy in Europe on the foundation of a powerful merchant class and a republican form of government. The Dutch economy was based on a mutually supportive industry of agriculture, fishing and international cargo trading. At their command was a huge navy and merchant fleet of fluyts, cargo ships specially designed to sail through the world, which controlled a large percentage of the international trade. In 1595 the first Dutch ships sailed for the East Indies. The Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC as it was known) was established in 1602 and competed directly with Spain and Portugal for the spices of the Far East and the Indian subcontinent. The success of the VOC encouraged the Dutch to expand to the Americas where they established colonies in Brazil, Curacao and the Virgin Islands. -

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam)

Gabriel Metsu (Leiden 1629 – 1667 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Gabriel Metsu” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/gabriel- metsu/ (accessed September 28, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Gabriel Metsu Page 2 of 5 Gabriel Metsu was born sometime in late 1629. His parents were the painter Jacques Metsu (ca. 1588–1629) and the midwife Jacquemijn Garniers (ca. 1590–1651).[1] Before settling in Leiden around 1615, Metsu’s father spent some time in Gouda, earning his living as a painter of patterns for tapestry manufacturers. No work by Jacques is known, nor do paintings attributed to him appear in Leiden inventories.[2] Both of Metsu’s parents came from Southwest Flanders, but when they were still children their families moved to the Dutch Republic. When the couple wed in Leiden in 1625, neither was young and both had previously been married. Jacquemijn’s second husband, Guilliam Fermout (d. ca. 1624) from Dordrecht, had also been a painter. Jacques Metsu never knew his son, for he died eight months before Metsu was born.[3] In 1636 his widow took a fourth husband, Cornelis Bontecraey (d. 1649), an inland water skipper with sufficient means to provide well for Metsu, as well as for his half-brother and two half-sisters—all three from Jacquemijn’s first marriage. -

Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2-24-2014 Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672 David Beeler University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Beeler, David, "Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4983 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672 by David Beeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Cornelis “Kees” Boterbloem, Ph.D. Brendan Cook, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 24, 2014 Keywords: colonialism, foreign, otherness, maidservant, Burgher, mercenary Copyright © 2014, David Beeler Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................................ii -

Willem Van Aelst 1627-1683 Rare Pair of Flower Baskets

anticSwiss 30/09/2021 18:52:26 http://www.anticswiss.com Willem van Aelst 1627-1683 Rare Pair of Flower Baskets SOLD ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 17° secolo -1600 ARTE TRES GALLERY * SAS EP Style: NEVIAN Luigi XIV Reggenza +33 950 597 650 Height:59.5cm 33777727626 Width:78.5cm Price:2650€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: Beautiful Pair of Oils on canvas, Antwerp School 17th, attributed to Willem van Aelst 1627-1683, Or to his Atelier Compositions Florales in a basket and an entablature. Beautiful dimensions: 78.5 cm x 59.5 cm (View 67 cm x 50 cm) In their juice, untouched, traces folds, 19th frame, beautiful golden framed vintage. Very neat shipping accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity and an Invoice. Participation in shipping costs for France: 60 €, for other countries, please ask for a quotation ... Willem van Aelst (Utrecht (?), 1625 or 1626 - Amsterdam, around 1683) is a painter of still life of flowers and Dutch hunting (United Provinces) of the Golden Century. His work is remarkable for the skill of his compositions - he introduced asymmetry in the still life - and the skilful harmony of his colors. Willem van Aelst was born of a father notary. He studied painting in Delft, with his uncle, the painter of still life Evert van Aelst. On November 9, 1643, van Aelst was admitted to the guild of Saint-Luc. From 1645 to 1649, he lives in France, which will be important for the development of his art. He then undertook a trip to Italy, where he remained from 1649 to 1656. In Rome, van Aelst was a member of the Bentvueghels, among which he would have been called "Vogelverschrikker" ("Scarecrow"); nothing, however, bears witness to the presence of the artist in this city. -

The Five Senses in Genre Paintings of the Dutch Golden Age

The Five Senses in Genre Paintings of the Dutch Golden Age Kitsirin Kitisakon+ (Thailand) Abstract This article aims to study one of the most popular themes in 17th-Century Dutch genre paintings - the five senses - in its forms and religious interpretations. Firstly, while two means of representation were used to clearly illustrate the subject, some genre scenes could also be read on a subtle level; this effectively means that such five senses images can be interpreted somewhere between clarity and am- biguity. Secondly, three distinct religious meanings were identified in these genre paintings. Vanity was associated with the theme because the pursuit of pleasure is futile, while sin was believed to be committed via sensory organs. As for the Parable of the Prodigal Son, party scenes alluding to the five senses can be read as relating to the episode of the son having spent all his fortune. Keywords: Five Senses, Genre Painting, Dutch Golden Age, Prodigal Son + Dr. Kitsirin Kitisakon, Lecturer, Visual Arts Dept., Faculty of Fine and Applied Art, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. The Five Senses… | 125 Introduction In the 16th and 17th Centuries, the five senses had never been more popular as subject matter for graphic art, especially in the Low Countries. Since Nordenfalk (1985), this theme has been occasionally discussed in monographs, catalogues of specific artists, or Dutch genre painting studies. Yet, an analysis of the modes of representation of the five senses seems to have been ignored, and there is a certain lack of fresh interest in their religious interpretations. From this observa- tion, this article aims to firstly examine how the five senses were represented in the Dutch genre paintings of the Golden Age, inspect how artists narrated them; secondly, reinvestigate how they can be religiously interpreted and propose deeper meanings which go beyond realistic appearance. -

Deborah Moggach, Zbigniew Herbert and Dutch Painting of the Seventeenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Studia Litteraria Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 10 (2015), z. 2, s. 131–151 doi: 10.4467/20843933ST.15.012.4103 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Litteraria MAREK KUCHARSKI Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie e-mail: [email protected] Intertextual and Intermedial Relationships: Deborah Moggach, Zbigniew Herbert and Dutch Painting of the Seventeenth Century Abstract The aim of the article is to analyse the intertextual and intermedial relationships between Tulip Fever, a novel by Deborah Moggach, The Bitter Smell of Tulips, an essay by Zbigniew Herbert from the collection Still Life with a Bridle, with some selected examples of Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century. As Moggach does not confi ne herself only to the aforementioned essay by Herbert, I will also refer to other essays from the volume as well as to the essay Mistrz z Delft which comes from the collection of the same title. Keywords: Deborah Moggach, Zbigniew Herbert, novel, essay, Dutch paintings, intertextuality, intermediality. Zbigniew Herbert’s essay The Bitter Smell of Tulips comes from the collection Still Life with a Bridle which is a part of the trilogy that, apart from the afore- mentioned collection of essays, consists of two other volumes: Labyrinth on the Sea and Barbarian in the Garden. In each of the volumes, in the form of a very personal account of his travels, Herbert spins a yarn of European culture and civi- lization. Labyrinth on the Sea focuses on the history and culture of ancient Greece and Rome whereas in Barbarian in the Garden Herbert draws on the whole spec- trum of subjects ranging from the prehistoric paintings on the walls of the cave in Lascaux, through the Gothic cathedrals and Renaissance masterpieces, to the stories about the Albigensians and the persecution of the Knights of the Templar Order. -

The Art Market in the Dutch Golden

The Art Market in the Dutch Art 1600–1700 Dutch Golden Age The first great free market economy for art This painting is occurred in the Dutch Republic of the 1600s. an example of the This republic was the most wealthy and “history painting” urbanized nation at the time. Its wealth was category. based on local industries such as textiles and breweries and the domination of the global trade market by the Dutch East India Company. This economic power translated into a sizeable urban middle class with disposable income to purchase art. As a result of the Protestant Reformation, and the absence of liturgical painting in the Protestant Church, religious patronage was no longer a major source of income for artists. Rather than working on commission, artists sold their paintings on an open market in bookstores, fairs, and through dealers. (c o n t i n u e d o n b a c k ) Jan Steen (Dutch, 1626–1679). Esther, Ahasuerus, and Haman, about 1668. Oil on canvas; 38 x 47 1/16 in. John L. Severance Fund 1964.153 Dutch Art 1600–1700 Still-life paintings like this one were often less expen- sive than history paintings. (c o n t i n u e d f r o m f r o n t ) This open market led to the rise in five major categories of painting: history painting, portraiture, scenes of everyday life, landscapes, and still-life paintings. The most prized, most expensive, and often largest in scale were history or narrative paintings, often with biblical or allegorical themes. -

Painting in the Dutch Golden

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART | DIVISION OF EDUCATION Age Golden Dutch the in Painting DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION PUBLICATIONS Painting in the Dutch Golden Age Classroom Guide Classroom Guide NATIO N AL GALLERY OF OF GALLERY AL A RT, WASHI RT, NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART NG WASHINGTON TO N Painting in the Dutch Golden Age Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON Contents How to Use This Booklet 1 1 Profile of the Dutch Republic 3 BACKSTORY Topography 4 A Unique Land 5 The Challenges of Water Today 7 BACKSTORY Cities 8 Location, Location, Location 9 BACKSTORY Government 13 A New Republican Government 15 Parallels between Dutch and U.S. Independence 16 Terms, Supplemental Materials, and Other Resources 18 2 A Golden Age for the Arts 21 BACKSTORY 22 What Do You Know and What Can You See? 23 Why Do We Like It? 25 Forged! 27 Where We Look at Art 29 Stories behind the Art 29 Terms, Supplemental Materials, and Other Resources 30 3 Life in the City and Countryside 31 7 Portraiture 59 BACKSTORY 32 BACKSTORY 60 One Skater, Two Skaters... 35 Fashion, Attitude, and Setting — Then and Now 61 Seventeenth-Century Winters 36 What Might Each Picture Tell You about Terms and Other Resources 38 Its Subject? 63 Supplemental Materials and Other Resources 64 4 Landscape Painting 39 BACKSTORY 40 8 History Painting 65 Approaches to Landscape Painting 41 BACKSTORY 66 Narrative and Non-narrative Painting 43 Rembrandt and Biblical Stories 68 Terms and Supplemental Materials 44 Contrasting Narrative Strategies in History Painting 69 5 Genre Painting 45 Picturing the