The Artful Context of Rembrandt's Etching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638)

CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638) _____________ The Last Supper Signed with monogram and dated 1636, lower centre On panel – 14¾ x 17⅜ ins (37.4 x 44.2 cm) Provenance: Private collection, United Kingdom since the early twentieth century VP 3691 The Last Supperi which Christ took with the disciples in Jerusalem before his arrest has been a popular theme in Christian art from the time of Leonardo. Cornelis van Haarlem sets the scene in a darkened room, lit only by candlelight. Christ is seated, with outstretched arms, at the centre of a long table, surrounded by the twelve apostles. The artist depicts the moment following Christ’s prediction that one among the assembled company will betray him. The drama focuses upon the reactions of the disciples, as they turn to one another, with gestures of surprise and disbelief. John can be identified as the apostle sitting in front of Christ who, as the gospel relates, ‘leaned back close to Jesus and asked, “Lord, who is it?”ii and Andrew, an old man with a forked beard, can be seen at the right-hand end of the table. Only Judas, recognisable by the purse of money he holds in his right handiii, turns away from the table and casts a shifty glance towards the viewer. The bread rolls on the table and the wine flagon held by the apostle on the right make reference to the sacrament of the eucharist. This previously unrecorded painting, dating from 1636, is a late work by Cornelis van Haarlem and is characteristic of the moderate classicism which informed his work from around 1600 onwards. -

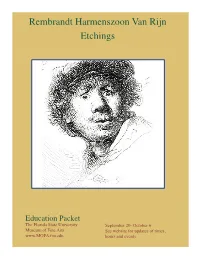

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

MAGIS Brugge

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 7 Article 3 Issue 2 Cartographic Styles and Discourse 2018 MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th- century Map through its 21st-century Digitization Elien Vernackt Musea Brugge and Kenniscentrum vzw, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Vernackt, Elien. "MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th-century Map through its 21st-century Digitization." Artl@s Bulletin 7, no. 2 (2018): Article 3. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Cartographic Styles and Discourse MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th-century Map through its 21st-century Digitization Elien Vernackt * MAGIS Brugge Project Abstract Marcus Gerards delivered his town plan of Bruges in 1562 and managed to capture the imagination of viewers ever since. The 21st-century digitization project MAGIS Brugge, supported by the Flemish government, has helped to treat this map as a primary source worthy of examination itself, rather than as a decorative illustration for local history. A historical database was built on top of it, with the analytic method called ‘Digital Thematic Deconstruction.’ This enabled scholars to study formally overlooked details, like how it was that Gerards was able to balance the requirements of his patrons against his own needs as an artist and humanist Abstract Marcus Gerards slaagde erin om tot de verbeelding te blijven spreken sinds hij zijn plan van Brugge afwerkte in 1562. -

SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER: HUDSON VALLEY a Field Guide to Mindful Travel Through Drawing & Writing

SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER: HUDSON VALLEY A Field Guide to Mindful Travel through Drawing & Writing MATERIALS & EQUIPMENT Anything that makes a mark, and any surface that takes a mark will be perfectly suitable. If you prefer to go to the field accoutered in style, below is a list of optional supplies. SKETCHBOOKS FIELD ARTIST. Watercolor sketchbooks. Various sizes. MOLESKINE. Watercolor sketchbooks. Various sizes. HAND BOOK. Watercolor sketchbook. Various sizes. Recommended: Moleskine Watercolor Sketchbook BRUSHES DAVINCI Travel brushes. https://www.amazon.com/Vinci-CosmoTop-Watercolor-Synthetic- Protective/dp/B00409FCLE/ref=sr_1_4?crid=159I8HND5YMOY&dchild=1&keywords=da+vinci+t ravel+watercolor+brushes&qid=1604518669&s=arts-crafts&sprefix=da+vinci+travel+%2Carts- crafts%2C159&sr=1-4 ESCODA Travel brushes. https://www.amazon.com/Escoda-1468-Travel-Brush- Set/dp/B00CVB62U8 RICHESON Plein air watercolor brush set. https://products.richesonart.com/products/gm- travel-sets WATERCOLORS: Tube and Half-Pans WATERCOLORS L. CORNELISSEN & SON. (London) Full selection of pans, tubes, and related materials. Retail walk-in and online sales. https://www.cornelissen.com MAIMERI. Watercolors. Italy. http://www.maimeri.it GOLDEN PAINTS. QoR Watercolors (recommended) The gold standard in acrylic colors for artists, Golden has developed a new line of watercolors marketed as QoR. It has terrific pigment density and uses a water-soluble synthetic binder in place of Gum Arabic https://www.qorcolors.com KREMER PIGMENTE. (Germany & NYC) Selection of travel sets and related materials. Online and walk-in retail sales. https://shop.kremerpigments.com/en/ SAVOIR-FAIRE is the official representative of Sennelier products in the USA. Also carries a full selection of brushes, papers and miscellaneous equipment. -

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] THE MORGAN HOSTS MAJOR EXHIBITION OF MASTER DRAWINGS FROM MUNICH’S FAMED STAATLICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG SHOW INCLUDES WORKS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE MODERN PERIOD AND MARKS THE FIRST TIME THE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG HAS LENT SUCH AN IMPORTANT GROUP OF DRAWINGS TO AN AMERICAN MUSEUM Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich October 12, 2012–January 6, 2013 **Press Preview: Thursday, October 11, 10 a.m. until 11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, August 25, 2012—This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum will host an extraordinary exhibition of rarely- seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection. The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

ARTIST Is in Caps and Min of 6 Spaces from the Top to Fit in Before

PAUL BRIL (Antwerp c. 1554 – 1626 Rome) A Landscape with a Hunting Party and Roman Ruins On canvas, 27¾ x 38 ¾ ins. (70.5 x 98.4 cm) Provenance: The Duke of Sutherland, Dunrobin Castle, by 1921 By whom sold, Christie’s, London, 29 November 1957, lot 31 Where purchased by Thos. Agnew & Sons, London Denys Sutton (1917-1991), London Thence by descent to the previous owner Exhibited: Thos. Agnew & Sons Ltd., London, 1958 Ideal & Classical Landscape, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, 6 February – 3 April 1960, cat. no. 18 L’Ideale classico del Seicento in Italia e la pittura di paesaggio, Bologna, 8 September – 11 November, 1962, cat. no. 124 Literature: The Duke of Sutherland, Dunrobin Castle Catalogue, 1921, no. 253 Art News, April 1958, vol. 57, no. 2, p. 4 (reproduced) F. Cappelletti, Paul Bril, et la pittura di paesaggio a Roma 1580- 1630, Rome, 2005, p. 304, cat. no. 166 (reproduced) Note: We are grateful to Drs. Luuk Pijl for confirming the attribution to Bril, based on photographs. Drs. Pijl dates the work to between 1617-1620 and will include it in his forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Paul Bril’s paintings. VP4601 Paul Bril trained in Antwerp before making his way to Italy sometime before 1582. In Rome, he joined his older brother Matthijs (c. 1550-83), who was already established in the employment of Pope Gregory XIII, producing fresco decorations for the Vatican. Initially, Paul assisted his brother, but after Matthijs’s premature death in 1583, he assumed responsibility for the papal commissions both in the Vatican and in various churches and villas in and around Rome. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THAT TEACHES YOU HOW to DRAW! Always Wanted to Learn How to Draw? Now’S Your Chance

Final spine = 0.75 in. Book trims with rounded corners THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THAT TEACHES YOU HOW TO HOW YOU TEACHES THAT THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THAT TEACHES YOU HOW TO DRAW! Always wanted to learn how to draw? Now’s your chance. Kean University Teacher of the Year Robin Landa has cleverly disguised an entire college-level course on drawing in this fun, hands-on, begging-to-be-drawn-in sketchbook. Even if you’re one of the four people on this planet who have never picked up a pencil before, you will learn how to transform your doodles into realistic drawings that actually resemble what you’re picturing in your head. In this book, you will learn how to use all of the formal elements of drawing—line, shape, value, color, pattern, and texture—to create well-composed still lifes, landscapes, human figures, and faces. Keep your pencils handy while you’re reading because you’re going to get plenty of drawing breaks— and you can do most of them right in the book while the techniques are fresh in your mind. To keep you inspired, Landa breaks up the step-by-step instruction with drawing suggestions and examples from a host of creative contributors including designers Stefan G. Bucher and Jennifer Sterling, artist Greg Leshé, illustrator Mary Ann Smith, animator Hsinping Pan, and more. Robin Landa, Distinguished Professor in the Robert Busch School of Design at Kean University, draws, designs, and has written 21 books about art, design, creativity, advertising, and branding. Robin’s books include the bestseller Graphic Design Solutions (now in its 5th edition); Build Your Own Brand: Strategies, Prompts and Exercises for Marketing Yourself; and Take A Line For A Walk: A Creativity Journal. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

Rembrandt Remembers – 80 Years of Small Town Life

Rembrandt School Song Purple and white, we’re fighting for you, We’ll fight for all things that you can do, Basketball, baseball, any old game, We’ll stand beside you just the same, And when our colors go by We’ll shout for you, Rembrandt High And we'll stand and cheer and shout We’re loyal to Rembrandt High, Rah! Rah! Rah! School colors: Purple and White Nickname: Raiders and Raiderettes Rembrandt Remembers: 80 Years of Small-Town Life Compiled and Edited by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins Des Moines, Iowa and Harrisonburg, Virginia Copyright © 2002 by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins All rights reserved. iii Table of Contents I. Introduction . v Notes on Editing . vi Acknowledgements . vi II. Graduates 1920s: Clifford Green (p. 1), Hilda Hegna Odor (p. 2), Catherine Grigsby Kestel (p. 4), Genevieve Rystad Boese (p. 5), Waldo Pingel (p. 6) 1930s: Orva Kaasa Goodman (p. 8), Alvin Mosbo (p. 9), Marjorie Whitaker Pritchard (p. 11), Nancy Bork Lind (p. 12), Rosella Kidman Avansino (p. 13), Clayton Olson (p. 14), Agnes Rystad Enderson (p. 16), Alice Haroldson Halverson (p. 16), Evelyn Junkermeier Benna (p. 18), Edith Grodahl Bates (p. 24), Agnes Lerud Peteler (p. 26), Arlene Burwell Cannoy (p. 28 ), Catherine Pingel Sokol (p. 29), Loren Green (p. 30), Phyllis Johnson Gring (p. 34), Ken Hadenfeldt (p. 35), Lloyd Pressel (p. 38), Harry Edwall (p. 40), Lois Ann Johnson Mathison (p. 42), Marv Erichsen (p. 43), Ruth Hill Shankel (p. 45), Wes Wallace (p. 46) 1940s: Clement Kevane (p. 48), Delores Lady Risvold (p.