CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAGIS Brugge

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 7 Article 3 Issue 2 Cartographic Styles and Discourse 2018 MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th- century Map through its 21st-century Digitization Elien Vernackt Musea Brugge and Kenniscentrum vzw, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Vernackt, Elien. "MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th-century Map through its 21st-century Digitization." Artl@s Bulletin 7, no. 2 (2018): Article 3. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Cartographic Styles and Discourse MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th-century Map through its 21st-century Digitization Elien Vernackt * MAGIS Brugge Project Abstract Marcus Gerards delivered his town plan of Bruges in 1562 and managed to capture the imagination of viewers ever since. The 21st-century digitization project MAGIS Brugge, supported by the Flemish government, has helped to treat this map as a primary source worthy of examination itself, rather than as a decorative illustration for local history. A historical database was built on top of it, with the analytic method called ‘Digital Thematic Deconstruction.’ This enabled scholars to study formally overlooked details, like how it was that Gerards was able to balance the requirements of his patrons against his own needs as an artist and humanist Abstract Marcus Gerards slaagde erin om tot de verbeelding te blijven spreken sinds hij zijn plan van Brugge afwerkte in 1562. -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis Van Haarlem’S Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon

History of Art MA Dissertation, 2017 Ruptured Wisdom: The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon Cornelis van Haarlem, Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon, 1588 History of Art MA – University College London HART G099 Dissertation September 2017 Supervisor: Allison Stielau Word Count: 13,999 Candidate Number: QBNB8 1 History of Art MA Dissertation, 2017 Ruptured Wisdom: The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon Striding into the wood, he encountered a welter of corpses, above them the huge-backed monster gloating in grisly triumph, tongue bedabbled with blood as he lapped at their pitiful wounds. -Ovid, Metamorphoses, III: 55-57 Introduction The visual impact of the painting Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon (figs.1&2), is simultaneously disturbing and alluring. Languidly biting into a face, the dragon stares out of the canvas fixing the viewer in its gaze, as its unfortunate victim fails to push it away, hand resting on its neck, raised arm slackened into a gentle curve, the parody of an embrace as his fight seeps away with his life. A second victim lies on top of the first, this time fixed in place by claws dug deeply into the thigh and torso causing the skin to corrugate, subcutaneous tissue exposed as blood begins to trickle down pale flesh. Situated at right angles to each other, there is no opportunity for these bodies to be fused into a single cohesive entity despite one ending where the other begins. -

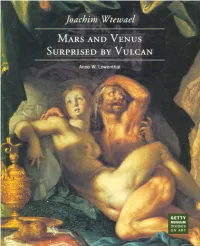

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities ~ .~ I1{, ~ -1~, dr \ --"-x r-i>- : ........ :i ' i 1 ~,1": "~ .-~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1984---May 1985 Washington, 1985 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without thc written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1985 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Gavarni, "Les Artistes," no. 2 (printed by Aubert et Cie.), published in Le Charivari, 24 May 1838. "Vois-tu camarade. Voil~ comme tu trouveras toujours les vrais Artistes... se partageant tout." CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1984-1985 (June 1984-May 1985) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 16 Meetings 21 Members' Research Reports Reports 32 i !~t IJ ii~ . ~ ~ ~ i.~,~ ~ - ~'~,i'~,~ ii~ ~,i~i!~-i~ ~'~'S~.~~. ,~," ~'~ i , \ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

Cornelis Cornelisz, Who Himself Added 'Van Haarlem' to His Name, Was One of the Leading Figures of Dutch Mannerism, Together

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (Haarlem 1562 – 1638) Venus, Cupid and Ceres Oil on canvas 38 x 43 in. (96.7 x 109.2 cm.) Signed with monogram and dated upper right: ‘CH. 1604’ Provenance Private collection, New York Cornelis Cornelisz, who himself added ‘van Haarlem’ to his name, was one of the leading figures of Dutch Mannerism, together with his townsman Hendrick Goltzius and Abraham Bloemaert from Utrecht. He was born in 1562 in a well-to-do Catholic family in Haarlem, where he first studied with Pieter Pietersz. At the age of seventeen he went to France, but at Rouen he had to turn back to avoid an outbreak of the plague and went instead to Antwerp, where he remained for a year with Gilles Coignet. The artist returned to Haarlem in 1581, and two years later, in 1583, he received his first important commission for a group portrait of a Haarlem militia company (now in the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem). From roughly 1586 to 1591 Cornelis, together with Goltzius and Flemish émigré Karel van Mander formed a sort of “studio brotherhood” which became known as the ‘Haarlem Academy’. In the 1590’s he continued to receive many important commissions from the Municipality and other institutions. Before 1603, he married the daughter of a Haarlem burgomaster. In 1605, he inherited a third of his wealthy father-in-law’s estate; his wife died the following year. From an illicit union with Margriet Pouwelsdr, Cornelis had a daughter Maria in 1611. -

"MAN with a BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED to FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION and SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian

Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies Fogg Art Museum Harvard University 1'1 Ii I "MAN WITH A BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED TO FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION AND SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian July 1984 ___~.~J INDEX Abst act 3 In oduction 4 ans Hals, his school and circle 6 Writings of Carel van Mander Technical examination: A. visual examination 11 B ultra-violet 14 C infra-red 15 D IR-reflectography 15 E painting materials 16 F interpretatio of the X-radiograph 25 G remarks 28 Painting technique in the 17th c 29 Painting technique of the "Man with a Beer Keg" 30 General Observations 34 Comparison to other paintings by Hals 36 Cone usions 39 Appendix 40 Acknowl ement 41 Notes and References 42 Bibliog aphy 51 ---~ I ABSTRACT The "Man with a Beer Keg" attributed to Frans Hals came to the Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies for technical examination, pigment analysis and restoration. A series of samples was taken and cross-sections were prepared. The pigments and the binding medium were identified and compared to the materials readily available in 17th century Holland. Black and white, infra-red and ultra-violet photographs as well as X-radiographs were taken and are discussed. The results of this study were compared to 17th c. materials and techniques and to the literature. 3 INTRODUCTION The "Man with a Beer Keg" (oil on canvas 83cm x 66cm), painted around 1630 - 1633) appears in the literature in 1932. [1] It was discovered in London in 1930. It had been in private hands and was, at the time, celebrated as an example of an unsuspected and startling find of an old master. -

In 1590, the Dutch Painter and Printmaker Hendrick Goltzius (Fig. 1)

THE BEER OF BACCHUS VISUAL STRATEGIES AND MORAL VALUES IN HENDRICK GOLTzius’ REPRESENTATIONS OF SINE CERERE ET LIBERO FRIGET VENUS Ricardo De Mambro Santos n 1590, the Dutch painter and printmaker Hendrick Goltzius (Fig. 1) created a sim- Iple yet refined composition representing a motif directly borrowed from Terence’s Eunuchus, namely the sentence Sine Cerere et Libero friget Venus (« Without Ceres and 1 Bacchus, Venus would freeze »). Sixteen years later, around 1606, after having depicted several times the same subject in very different compositions, the master elaborated his last representation of this theme in a most monumental pen werck (‘pen work’), in which he included a self-portrait staring at the viewer and holding in both hands the 2 tools of his metamorphic art : the burins. Many scholarly publications have correctly identified the textual source of these works and, therefore, analysed Goltzius’ visual constructions in strict relation to Terence’s play, stressing that the sentence was used 3 « to describe wine and food as precondition for love ». In spite of such a systematic attention, however, no research has been undertaken in the attempt to historically interpret Goltzius’ works within their original context of production, in connection with the social, artistic and economic boundaries of their first ambient of reception, the towns of Haarlem and Amsterdam at the turn of the centuries. As I shall demonstrate in this paper, the creation of such a coherent corpus of prints, drawings and paintings is directly associated -

Jaarverslag 2013

JaarverslagJaarverslag 2012 2013 Frans Hals Museum | De Hallen Haarlem Jaarverslag 2013 Frans Hals Museum Inhoud Sinds het Frans Hals Museum in 1913 zijn poorten aan het Groot Heiligland opende, heeft het zich in een toenemende faam en belangstelling mogen verheugen. De col- Bericht van de Raad van Toezicht p. 4 lectie van Haarlemse meesters uit de Gouden Eeuw, waaronder de grootste verzame- Voorwoord p. 6 ling schilderijen van Frans Hals ter wereld, is uniek. Aan het begin van de zeventien- de eeuw onderging de schilderkunst een radicale verandering, waarvoor in Haarlem Tentoonstellingen p. 15 de basis werd gelegd. Deze omslag bepaalde uiteindelijk de allure en de grandeur Frans Hals Museum van de Gouden Eeuw, waardoor Haarlem met recht kan worden aangemerkt als De Hallen Haarlem de bakermat van de Gouden Eeuw. De collectie van het Frans Hals Museum, Publicaties waarin het hele spectrum van de zestiende- en zeventiende-eeuwse schilderkunst op bijzonder hoog niveau is samengevat, weerspiegelt die revolutionaire omwenteling. Collectie p. 29 Aankopen De Hallen Haarlem Schenkingen Zoals Haarlem in de zeventiende eeuw een vrijhaven vormde voor de vernieuwings- Bruiklenen drang die zich in de kunst voordeed, zo wil De Hallen Haarlem ook nu een podium Registratie en inventarisatie bieden voor de ontwikkelingen die zich binnen de hedendaagse kunst aandienen. Restauraties Ze wil eenzelfde open, proactieve houding aan de dag leggen. Vernieuwingen roe- Activiteiten restauratoren pen, zeker als ze bestaande grenzen overschrijden en geldende normen openbreken, altijd weerstand op. De Hallen Haarlem wil die confrontatie evenwel niet uit de weg Publiekszaken p. 37 gaan en doelbewust dat spanningsgebied opzoeken. -

Courant 7/December 2003

codart Courant 7/December 2003 codartCourant contents Published by Stichting codart P.O. Box 76709 2 A word from the director 12 The influence and uses of Flemish painting nl-1070 ka Amsterdam 3 News and notes from around the world in colonial Peru The Netherlands 3 Australia, Melbourne, National Gallery 14 Preview of upcoming exhibitions [email protected] of Victoria 15 codartpublications: A window on www.codart.nl 3 Around Canada Dutch cultural organizations for Russian 4 France, Paris, Institut Néerlandais, art historians Managing editor: Rachel Esner Fondation Custodia 15 codartactivities in fall 2003 e [email protected] 4 Germany, Dresden, Staatliche Kunst- 15 Study trip to New England, sammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie 29 October-3 November 2003 Editors: Wietske Donkersloot, Alte Meister 23 codartactivities in 2004 Gary Schwartz 5 Germany, Munich, Staatliche 23 codart zevencongress: Dutch t +31 (0)20 305 4515 Graphische Sammlung and Flemish art in Poland, Utrecht, f +31 (0)20 305 4500 6 Italy, Bert W. Meijer’s influential role in 7-9 March 2004 e [email protected] study and research projects on Dutch 23 Study trip to Gdan´sk, Warsaw and and Flemish art in Italy Kraków, 18-25 April 2004 codart board 8 Around Japan 32 Appointments Henk van der Walle, chairman 8 Romania, Sibiu, Brukenthal Museum 32 codartmembership news Wim Jacobs, controller of the Instituut 9 Around the United Kingdom and 33 Membership directory Collectie Nederland, secretary- Ireland 44 codartdates treasurer 10 A typical codartstory Rudi Ekkart, director of the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie Jan Houwert, director of the Wegener Publishing Company Paul Huvenne, director of the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp Jeltje van Nieuwenhoven, member of the Dutch Labor Party faction codartis an international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. -

Self-Portraiture 1400-1700

9 Self-Portraiture 1400–1700 H. Perry Chapman In his biography of Albrecht Dürer, published in Het schilder-boeck (The Painter Book, 1604), Karel van Mander describes holding in his hands Dürer’s Self- Portrait of 1500 (fig. 9.1).1 Van Mander, the Dutch painter-biographer who wrote the lives of the Netherlandish and German painters (see chapter 24), was on his way home from Italy in 1577. He had stopped in Nuremberg, where he saw Dürer’s Self-Portrait in the town hall. Van Mander’s account conveys Dürer’s fame, as both the greatest German artist of the Renaissance and a maker of self- portraits. It tells us that self-portraits were collected and displayed, in this case by the city of Nuremberg. Above all, Van Mander’s remarks demonstrate that, by 1600, self-portrait was a concept. Though there was as yet no term for self- portrait (autoritratto dates to the eighteenth century, Selbstbildniss and “self-portrait” to the nineteenth), a portrait of an artist made by that artist was regarded as a distinctive pictorial type. The self-portrait had acquired a mystique, because the artist had come to be regarded as a special person with a special gift. The topos “every painter paints himself” conveyed the idea that a painter invariably put something of him/herself into his/her art. More than any other kind of artistic creation, the self-portrait was regarded as a manifestation of the artist’s ineffable presence in the work. Today we tend to think of self-portrayal as a private process and of the self- portrait as the product of introspection.