In 1590, the Dutch Painter and Printmaker Hendrick Goltzius (Fig. 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638)

CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638) _____________ The Last Supper Signed with monogram and dated 1636, lower centre On panel – 14¾ x 17⅜ ins (37.4 x 44.2 cm) Provenance: Private collection, United Kingdom since the early twentieth century VP 3691 The Last Supperi which Christ took with the disciples in Jerusalem before his arrest has been a popular theme in Christian art from the time of Leonardo. Cornelis van Haarlem sets the scene in a darkened room, lit only by candlelight. Christ is seated, with outstretched arms, at the centre of a long table, surrounded by the twelve apostles. The artist depicts the moment following Christ’s prediction that one among the assembled company will betray him. The drama focuses upon the reactions of the disciples, as they turn to one another, with gestures of surprise and disbelief. John can be identified as the apostle sitting in front of Christ who, as the gospel relates, ‘leaned back close to Jesus and asked, “Lord, who is it?”ii and Andrew, an old man with a forked beard, can be seen at the right-hand end of the table. Only Judas, recognisable by the purse of money he holds in his right handiii, turns away from the table and casts a shifty glance towards the viewer. The bread rolls on the table and the wine flagon held by the apostle on the right make reference to the sacrament of the eucharist. This previously unrecorded painting, dating from 1636, is a late work by Cornelis van Haarlem and is characteristic of the moderate classicism which informed his work from around 1600 onwards. -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] THE MORGAN HOSTS MAJOR EXHIBITION OF MASTER DRAWINGS FROM MUNICH’S FAMED STAATLICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG SHOW INCLUDES WORKS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE MODERN PERIOD AND MARKS THE FIRST TIME THE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG HAS LENT SUCH AN IMPORTANT GROUP OF DRAWINGS TO AN AMERICAN MUSEUM Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich October 12, 2012–January 6, 2013 **Press Preview: Thursday, October 11, 10 a.m. until 11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, August 25, 2012—This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum will host an extraordinary exhibition of rarely- seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection. The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. -

Circle of Hendrick Goltzius, Study of a Male Lumpsucker

Circle of Hendrick Goltzius, Study of a Male Lumpsucker Carina Fryklund Curator, Old Master Drawings and Paintings Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 22 Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, © Stockholms Auktionsverk, Stockholm Graphic Design is published with generous support from (Fig. 5, p. 35) BIGG the Friends of the Nationalmuseum. © Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels (Fig. 2, p. 38) Layout Nationalmuseum collaborates with © Teylers Museum, Haarlem (Fig. 3, p. 39) Agneta Bervokk Svenska Dagbladet and Grand Hôtel Stockholm. © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Shelfmark: We would also like to thank FCB Fältman & Riserva.S.81(int.2) (Fig. 2, p. 42) Translation and Language Editing Malmén. © Galerie Tarantino, Paris (Figs. 3–4, p. 43) Gabriella Berggren, Erika Milburn and © Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain Martin Naylor Cover Illustration (Figs. 3–4, pp. 46–47) Anne Vallayer (1744–1818), Portrait of a Violinist, © National Library of Sweden, Stockholm Publishing 1773. Oil on canvas, 116 x 96 cm. Purchase: (Figs. 5–6, pp. 48–49) Janna Herder (Editor) and Ingrid Lindell The Wiros Fund. Nationalmuseum, NM 7297. © Uppsala Auktionskammare, Uppsala (Publications Manager) (Fig. 1, p. 51) Publisher © Landsarkivet, Gothenburg/Johan Pihlgren Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum is published Berndt Arell, Director General (Fig. 3, p. 55) annually and contains articles on the history and © Västergötlands museum, Skara (Fig. 4, p. 55) theory of art relating to the collections of the Editor © Svensk Form Design Archive/Centre for Nationalmuseum. Janna Herder Business History (Fig. 2, p. 58) © Svenskt Tenn Archive and Collection, Nationalmuseum Editorial Committee Stockholm (Fig. 4, p. 60) Box 16176 Janna Herder, Linda Hinners, Merit Laine, © Denise Grünstein (Fig. -

The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis Van Haarlem’S Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon

History of Art MA Dissertation, 2017 Ruptured Wisdom: The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon Cornelis van Haarlem, Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon, 1588 History of Art MA – University College London HART G099 Dissertation September 2017 Supervisor: Allison Stielau Word Count: 13,999 Candidate Number: QBNB8 1 History of Art MA Dissertation, 2017 Ruptured Wisdom: The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon Striding into the wood, he encountered a welter of corpses, above them the huge-backed monster gloating in grisly triumph, tongue bedabbled with blood as he lapped at their pitiful wounds. -Ovid, Metamorphoses, III: 55-57 Introduction The visual impact of the painting Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon (figs.1&2), is simultaneously disturbing and alluring. Languidly biting into a face, the dragon stares out of the canvas fixing the viewer in its gaze, as its unfortunate victim fails to push it away, hand resting on its neck, raised arm slackened into a gentle curve, the parody of an embrace as his fight seeps away with his life. A second victim lies on top of the first, this time fixed in place by claws dug deeply into the thigh and torso causing the skin to corrugate, subcutaneous tissue exposed as blood begins to trickle down pale flesh. Situated at right angles to each other, there is no opportunity for these bodies to be fused into a single cohesive entity despite one ending where the other begins. -

Afb. I, Cornelis Van Haarlem Zelfportret, Museum Te

AFB. I, CORNELIS VAN HAARLEM ZELFPORTRET, MUSEUM TE BRUSSEL CORNELIS VAN HAARLEM EN DE HOLLANDSCHE LAAT-MANIËRISTISCHE SCHILDERKUNST DOOR WOLFGANG STECHOW N de laatste jaren heeft de kunstgeschiedenis zich met bijzondere voor- liefde bezig gehouden met het probleem van het Maniërisme en wel om tweeërlei redenen. In de eerste plaats trachtte zij een definitie I te geven van het Maniërisme als stijl, daarnaast wilde zij zijn ont- wikkelingsgang in Europa vastleggen. Aan deze onderzoekingen ligt de op- vatting ten grondslag, dat men bij het Maniërisme niet te doen heeft met aesthetisch te verklaren bijzonderheden van enkele verschijningsvormen, afgeleid van een bepaalde stijlperiode, Renaissance of Barok, maar met een stijl op zich zelf, die zich tusschen Renaissance en Barok inschuift. Deze opvatting, aanvankelijk tegengesproken, wordt tegenwoordig vrijwel algemeen aanvaard, hoe onaangenaam de betiteling van dezen stijl ook moge klinken, maar.... ook Gothiek en Barok waren eens scheldnamen! Bij de bestudeering van de ontwikkeling van het Maniërisme in de ver- schillende landen kwamen de uiteenloopende nationale eigenaardigheden reeds in groote trekken vast te staan. Deze nieuwe stijl ontkiemt in Italië reeds tijdens de korte periode, die wij gewoonlijk Hoog-renaissance noemen. Hij put nog vitale krachten uit de gotische bestanddeelen van het Quattro- cento ; men kan zelfs zeggen dat middeleeuwsch gekleurde elementen mede het wezen van het Maniërisme schijnen te moeten bepalen. Van de verschil- lende duidelijk van elkaar te onderscheiden phasen, die deze stijl doorloopt, is de laatste periode aesthetisch het zwakst. Hieruit is mede te verklaren dat de volgende nieuwe stijl, de Barok, zich in scherpe oppositie tegen dit nu „gemaniëreerd" geworden Maniërisme begon te ontwikkelen; de namen van hen, die tegelijkertijd twee, onderling geheel verschillende, maar door hun afkeer van het Maniërisme toch verbonden stroomingen in den barok- stijl beheerschen, zijn Caravaggio en Carracci. -

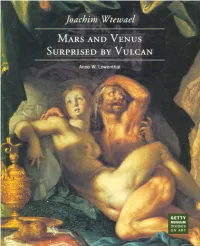

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan

Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Joachim Wtewael MARS AND VENUS SURPRISED BY VULCAN Anne W. Lowenthal GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Malibu, California Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Joachim Wtewael (Dutch, 1566-1638). Cynthia Newman Bohn, Editor Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, Amy Armstrong, Production Coordinator circa 1606-1610 [detail]. Oil on copper, Jeffrey Cohen, Designer 20.25 x 15.5 cm (8 x 6/8 in.). Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum (83.PC.274). © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Frontispiece: Malibu, California 90265-5799 Joachim Wtewael. Self-Portrait, 1601. Oil on panel, 98 x 74 cm (38^ x 29 in.). Utrecht, Mailing address: Centraal Museum (2264). P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 All works of art are reproduced (and photographs provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Library of Congress indicated. Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lowenthal, Anne W. Typography by G & S Typesetting, Inc., Joachim Wtewael : Mars and Venus Austin, Texas surprised by Vulcan / Anne W. Lowenthal. Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., p. cm. Hong Kong (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89236-304-5 i. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638. Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan. 2. Wtewael, Joachim, 1566-1638 — Criticism and inter- pretation. 3. Mars (Roman deity)—Art. 4. Venus (Roman deity)—Art. 5. Vulcan (Roman deity)—Art. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Title. III. Series. ND653. W77A72 1995 759-9492-DC20 94-17632 CIP CONTENTS Telling the Tale i The Historical Niche 26 Variations 47 Vicissitudes 66 Notes 74 Selected Bibliography 81 Acknowledgments 88 TELLING THE TALE The Sun's loves we will relate. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities ~ .~ I1{, ~ -1~, dr \ --"-x r-i>- : ........ :i ' i 1 ~,1": "~ .-~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1984---May 1985 Washington, 1985 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without thc written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1985 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Gavarni, "Les Artistes," no. 2 (printed by Aubert et Cie.), published in Le Charivari, 24 May 1838. "Vois-tu camarade. Voil~ comme tu trouveras toujours les vrais Artistes... se partageant tout." CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1984-1985 (June 1984-May 1985) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 16 Meetings 21 Members' Research Reports Reports 32 i !~t IJ ii~ . ~ ~ ~ i.~,~ ~ - ~'~,i'~,~ ii~ ~,i~i!~-i~ ~'~'S~.~~. ,~," ~'~ i , \ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

Lawrence W. Nichols: the Paintings of Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). a Monograph and Catalogue Raisonné (= Aetas Aurea, Vol. XX

Lawrence W. Nichols: The Paintings of Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). A Monograph and Catalogue Raisonné (= Aetas Aurea, vol. XXII), Doornspijk: Davaco Publishers 2013 ISBN-13: 978-90-70288-28-0, 466 pages, 207 plates, € 275 Reviewed by: Christian Tico Seifert, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh This book has been long awaited and, to say it straightaway, the wait has been worthwhile. Hot on the heels of Marjolein Leesberg’s superb New Hollstein volumes on Hendrick Goltzius’s prints, Lawrence Nichols has finally published his magisterial monograph on the painter Goltzius.[1] It is a hefty, clothbound volume, beautifully designed and printed. The book opens with a chapter on the tantalising but crucial question why Goltzius in 1600, aged forty-two and famous across Europe as the most skilful engraver of his age, lay down the burin for- ever to take up brushes and oil paint. Nichols, rightly in my view, dismisses poor health and failing eyesight as the main reasons for Goltzius decision. However, it should be remembered that the one-year-old Goltzius had been severely burnt in an accident that left his right hand crippled for life. Decades of printmaking could have exhausted the strength of his hand. Certainly, holding pen and brush is physically easier than controlling the burin on a copper plate. Nichols carefully examines Goltzius’s prints and drawings and detects a ‘lifelong predilection for tonal gradation, if not actual color’ (21). His portrait drawings in red and black chalks, heightened with white and subtly washed, show him as a sensitive colourist, and his chiaroscuro woodcuts demonstrate his interest as a printmaker in colour. -

Cornelis Cornelisz, Who Himself Added 'Van Haarlem' to His Name, Was One of the Leading Figures of Dutch Mannerism, Together

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (Haarlem 1562 – 1638) Venus, Cupid and Ceres Oil on canvas 38 x 43 in. (96.7 x 109.2 cm.) Signed with monogram and dated upper right: ‘CH. 1604’ Provenance Private collection, New York Cornelis Cornelisz, who himself added ‘van Haarlem’ to his name, was one of the leading figures of Dutch Mannerism, together with his townsman Hendrick Goltzius and Abraham Bloemaert from Utrecht. He was born in 1562 in a well-to-do Catholic family in Haarlem, where he first studied with Pieter Pietersz. At the age of seventeen he went to France, but at Rouen he had to turn back to avoid an outbreak of the plague and went instead to Antwerp, where he remained for a year with Gilles Coignet. The artist returned to Haarlem in 1581, and two years later, in 1583, he received his first important commission for a group portrait of a Haarlem militia company (now in the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem). From roughly 1586 to 1591 Cornelis, together with Goltzius and Flemish émigré Karel van Mander formed a sort of “studio brotherhood” which became known as the ‘Haarlem Academy’. In the 1590’s he continued to receive many important commissions from the Municipality and other institutions. Before 1603, he married the daughter of a Haarlem burgomaster. In 1605, he inherited a third of his wealthy father-in-law’s estate; his wife died the following year. From an illicit union with Margriet Pouwelsdr, Cornelis had a daughter Maria in 1611. -

Following the Early Modern Engraver, 1480-1650 September 18, 2009-January 3, 2010

The Brilliant Line: Following the Early Modern Engraver, 1480-1650 September 18, 2009-January 3, 2010 When the first engravings appeared in southern Germany around 1430, the incision of metal was still the domain of goldsmiths and other metalworkers who used burins and punches to incise armor, liturgical objects, and jewelry with designs. As paper became widely available in Europe, some of these craftsmen recorded their designs by printing them with ink onto paper. Thus the art of engraving was born. An engraver drives a burin, a metal tool with a lozenge-shaped tip, into a prepared copperplate, creating recessed grooves that will capture ink. After the plate is inked and its flat surfaces wiped clean, the copperplate is forced through a press against dampened paper. The ink, pulled from inside the lines, transfers onto the paper, printing the incised image in reverse. Engraving has a wholly linear visual language. Its lines are distinguished by their precision, clarity, and completeness, qualities which, when printed, result in vigorous and distinctly brilliant patterns of marks. Because lines once incised are very difficult to remove, engraving promotes both a systematic approach to the copperplate and the repetition of proven formulas for creating tone, volume, texture, and light. The history of the medium is therefore defined by the rapid development of a shared technical knowledge passed among artists dispersed across Renaissance and Baroque (Early Modern) Europe—from the Rhine region of Germany to Florence, Nuremberg, Venice, Rome, Antwerp, and Paris. While engravers relied on systems of line passed down through generations, their craft was not mechanical.