Center 21 National Gallery of Art Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Center 21 Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogo Leonardo

LEONARDO DA VINCI OIL PAINTING REPRODUCTION ARTI FIORENTINE FIRENZE ITALY There is no artist more legendary than Leonardo. In the whole History of Art, no other name has created more discussions, debates and studies than the genius born in Vinci in 1452. Self-Portrait, 1515 Red Chalk on paper 33.3 x 21.6 cm. Biblioteca Reale Torino As far as we know, this extraordinary dra- wing is the only surviving self-portrait by the master. The Annunciation, 1474 tempera on panel 98 X 217 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi THE BATTLE OF ANGHIARI The Battle of Anghiari is a lost painting by Leonardo da Vinci. This is the finest known copy of Leonardo’s lost Battle of Anghiari fresco. It was made in the mid-16th century and then extended at the edges in the early 17th century by Rubens. The Benois Madonna, 1478 Oil on canvas 49.5x33 cm Hermitage Museum Originally painted on wood, It was transferred to canvas when It entered the Hermitage, during which time it was severely demaged GOLD LEAF FRAME DETAIL Woman Head, 1470-76 La Scapigliata, 1508 Paper 28 x 20 cm Oil on canvas 24.7 x 21 cm Galleria degli Uffizi Firenze Parma Galleria Nazionale Lady with an ermine, 1489-90 Oil on wood panel 54 x 39 cm Czartoryski Museum The subject of the portrait is identified as Cecilia Gallerani and was probably painted at a time when she was the mi- stress of Lodovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, and Leonardo was in the service of the Duke. Carved gold frame Ritratto di una sforza, 1495 Uomo vitruviano, 1490 Gesso e inchistro su pergamena Matita e inchiostro su carta 34x24 cm. -

3 LEONARDO Di Strinati Tancredi ING.Key

THE WORKS OF ART IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL REPRODUCTION THE THEORETICAL BACKGROUND The Impossible Exhibitions project derives from an instance of cultural democracy that has its precursors in Paul Valéry, Walter Benjamin and André Malraux. The project is also born of the awareness that in the age of the digital reproducibility of the work of art, the concepts of safeguarding and (cultural and economic) evaluation of the artistic patrimony inevitably enter not only the work as itself, but also its reproduction: “For a hundred years here, as soon as the history of art has escaped specialists, it has been the history of what can be photographed” (André Malraux). When one artist's work is spread over various museums, churches and private collections in different continents, it becomes almost impossible to mount monograph exhibitions that give a significant overall vision of the great past artist's work. It is even harder to create great exhibitions due to the museum directors’ growing – and understandable – unwillingness to loan the works, as well as the exorbitant costs of insurance and special security measures, which are inevitable for works of incalculable value. Impossible Exhibitions start from these premises. Chicago, Loyola University Museum of Art, 2005 Naples, San Domenico Maggiore, 2013/2014 THE WORKS OF ART IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL REPRODUCTION THE PROJECT In a single exhibition space, Impossible Exhibitions present a painter's entire oeuvre in the form of very high definition reproductions, making use of digital technology permitting reproductions that fully correspond to the original works. Utmost detail resolution, the rigorously 1:1 format (Leonardo's Last Supper reproduction occupies around 45 square meters!), the correct print tone – certified by a renowned art scholar – make these reproductions extraordinarily close to the originals. -

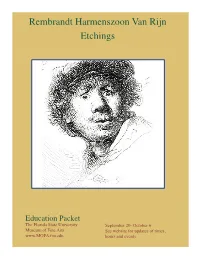

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

Francia – Forschungen Zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte Bd

Francia – Forschungen zur westeuropäischen Geschichte Bd. 35 2008 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online- Publikationsplattform der Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland (DGIA), zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Frederik Buylaert THE »VAN BOSCHUYSEN AFFAIR« IN LEYDEN Conflicts between Elite Networks in Late Medieval Holland1 Introduction The 1480s were a turbulent age in the city of Leyden in the county of Holland. In 1481 the city, which was controlled by the so-called Cod faction (Kabeljauwen), was briefly taken over by its opponents, the so-called Hooks (Hoeken). The city was again put in the hands of the Cods soon enough, but in 1486 the urban elite was again startled by another crisis. This disturbance was caused by the prominent Leyden nobleman Willem van Boschuysen, nicknamed »the Younger«. He was appointed sheriff (schout) of Leyden by the sovereign after the death of his predecessor, sheriff Adriaan van Zwieten, in August 1486. The sheriff of Leyden was an important figure. As local representative of sovereign authority, he also held a permanent place in the municipal authority of Leyden. The sheriff was not only involved in day-to-day government and ordinary city council jurisdiction, but also wielded high judicial power in the city. -

The Great Divergence the Princeton Economic History

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD Joel Mokyr, Editor Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815, by Philip T. Hoffman The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration, and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850–1914, by Timothy W. Guinnane Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory, by Cormac k Gráda The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, by Kenneth Pomeranz THE GREAT DIVERGENCE CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY Kenneth Pomeranz PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2000 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA POMERANZ, KENNETH THE GREAT DIVERGENCE : CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY / KENNETH POMERANZ. P. CM. — (THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD) INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00543-5 (CL : ALK. PAPER) 1. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—18TH CENTURY. 2. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—19TH CENTURY. 3. CHINA— ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—1644–1912. 4. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT—HISTORY. 5. COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS. I. TITLE. II. SERIES. HC240.P5965 2000 337—DC21 99-27681 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN TIMES ROMAN THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (PERMANENCE OF PAPER) WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3579108642 Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Cinema/Origini

CINEMA/ORIGINI N. 2 Collana diretta da Elena Dagrada (Università degli Studi di Milano) COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Elena Dagrada (Università degli Studi di Milano) Frank Kessler (Universiteit Utrecht) Michèle Lagny (Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris III) S A CABIRIA (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914) Lo spettacolo della Storia MIMESIS Cinema/origini © 2014 – M E (Milano – Udine) Isbn: 9788857521572 Collana: Cinema/origini, n. 2 www.mimesisedizioni.it Via Risorgimento, 33 – 20099 Sesto San Giovanni (MI) Telefono +39 02 24861657 / 02 24416383 Fax: +39 02 89403935 E-mail: [email protected] Immagine di copertina: Manifesto per un’edizione di Cabi- ria distribuita negli Stati Uniti dalla Latin Films Company nel 1921. Per Alberto Friedemann, amico e maestro INDICE I 11 C C 15 S 17 I 21 1. Gli anni d’oro del cinema italiano e il ruolo di Torino 21 2. Lo spettacolo della Storia 25 3. Un ragioniere alla conquista del mondo 29 I 37 1. Un making avventuroso 37 2. Il ruolo di D’Annunzio e la “parola-immagine” 43 3. Nazionalismo a bassa intensità 46 4. Un sistema di attrazioni 50 5. La conquista dello spazio e la rivoluzione scenografi ca 53 6. Il quadro mobile 60 7. La religione del fuoco 68 8. La scena onirica 75 9. Il gioco dei destini incrociati: l’offi cina del racconto dal soggetto al fi lm 79 10. Il fi lm che visse due volte 87 B 111 A 113 P C 115 CABIRIA (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914) Lo spettacolo della Storia 11 INTRODUZIONE Realizzato a Torino tra il 1913 e il 1914 da Gio- vanni Pastrone, Cabiria è senza dubbio il più celebre fi lm del cinema muto italiano e uno dei grandi miti culturali del Novecento. -

Zur Geschichte Des Italienischen Stummfilms

PD. Dr. Sabine Schrader Geschichte(n) des italienischen Stummfilms Sor Capanna 1919, S. 71 1896 Erste Vorführungen der Brüder Lumières in Rom 1905 Spielfilm La presa di Roma 1910-1915 Goldenes Zeitalter des italienischen Stummfilms 1920er US-amerikanische Übermacht 1926 Erste cinegiornali 1930 Erster italienischer Tonfilm XXXVII Mostra internazionale del Cinema Libero IL CINEMA RITROVATO Bologna 28.6.-5.7.2008 • http://www.cinetecadibologna.it/programmi /05cinema/programmi05.htm Istituto Luce a Roma • http://www.archivioluce.com/archivio/ Museo Nazionale del Cinema a Torino (Fondazione Maria Prolo) • http://www.museonazionaledelcinema.it/ • Alovisio, Silvio: Voci del silenzio. La sceneggiatura nel cinema muto italiano. Mailand / Turin 2005. • Redi, Riccardo: Cinema scritto. Il catalogo delle riviste italiane di cinema. Rom 1992. Vita Cinematografica 1912-7-15 Inferno (1911) R.: Francesco Bertolini / Adolfo Padovan / Giuseppe De Liguoro Mit der Musik von Tangerine Dream (2002) Kino der Attraktionen 1. „Kino der Attraktionen“ bis ca. 1906 2. Narratives Kino (etabliert sich zwischen 1906 und 1911) Gunning, Tom: „The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde”, in: Thomas Elsaesser (Hg.): Early Cinema: Space Frame Narrative. London 1990, S. 56-62 Vita Cinematografica 1913, passim Quo vadis? (1912/1913) R.: Enrico Guazzoni Mit der Musik von Umberto Petrin/ Nicola Arata La presa di roma (1905) Bernardini 1981 (2), 47. Cabiria (1914) R.: Giovanni Pastrone; Zwischentitel: u.a. D„Annunzio Kamera: u.a. Segundo de Chomòn -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

Hans Hartung (1904-1989) Abstraction: a Human Language

de Sarthe Gallery is pleased to announce Hans Hartung (1904-1989) Abstraction: A Human Language Opening: 4:30pm - 6:30pm, 25 November 2017 Duration: 25 November 2017 - 13 January 2018 Address: 20/F Global Trade Square, 21 Wong Chuk Hang Road, Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong de Sarthe Gallery is pleased to announce its second exhibition for Hans Hartung titled Abstraction: A Human Language. The show opens on November 25th, and will continue through January 13th, 2018. The exhibition will survey a selection of works from the 40s to the very end of his life in 80s. As early as 1945 Hans Hartung was regarded as one of the most important abstract expressionists. He was invited to the first Documenta at Kassel, in 1955 and was awarded the International Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1960 and had a major exhibition of his paintings in 1975 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Hartung’s works are in the collections of major museums worldwide including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Tate Gallery, London, Centre national d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, Paris and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. His prominent solo exhibitions include: Hartung in China, Palace of Fine Arts, Beijing, China; National Museum, Nanjing, China (2005); Hans Hartung: Spontaneous Calculus, Pictures, Photographs, Film 1922-1989, Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig, Germany; Kunsthalle Kiel, Kiel, Germany (2007-08); Hans Hartung: Essential, Circula de Bellas Artes, Madrid, Spain (2008); -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement.