Jacques Callot at the Medici Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

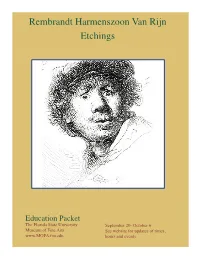

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

Mora Wade the RECEPTION of OPITZ's Ludith DURING the BAROQUE by Virtue of Its Status As the Second German Opera Libretto, Martin

Mora Wade THE RECEPTION OF OPITZ'S lUDITH DURING THE BAROQUE By virtue of its status as the second German opera libretto, Martin Opitz's ludith (1635), has received little critical attention in its own right. l ludith stands in the shadow of its predecessor, Da/ne (1627),2 also by Opitz, as weH as in that of a successor, Harsdörffer and Staden's See/ewig (1644), the first German-Ianguage opera to which the music is extant today.3 Both libretti by Opitz, Dafne and ludith, are the earliest examples of the reception of Italian opera into German-speaking lands.4 Da/ne was based on the opera ofthe 1. Martin Opitz: ludith. Breslau 1635. See also Kar! Goedeke: Grund risz zur Geschichte der deutschen Dichtung. Vol. III. Dresden 1886. p. 48. Aversion of this paper was given at the International Conference on the German Renaissance, Reformation, and Baroque held from 4-6 April 1986 at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. Support from the Newberry Library in Chicago and from the National Endowment for the Humani ties to use the Faber du Faur Collection at the Beinecke Library of Yale University enabled me to undertake and complete this project. A special thanks to Christa Sammons, curator of the German collection at the Beinecke, for providing me with a copy of ludith. 2. Martin Opitz: Dafne. Breslau 1627. 3. Georg Philipp Harsdörffer: Frauenzimmer Gesprächspiele. Vol. IV. Nürnberg 1644. Opitz's 'ludith' has only three acts and has no extant music. Löwenstern's music to Tscherning's expanded version of Opitz's 'ludith' was not published until 1646, a full two years after 'Seelewig'. -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

BIBLIOTECA DI GALILEO GALILEO's LIBRARY

Museo Galileo Istituto e Museo di storia della scienza Piazza Giudici 1, Firenze, ITALIA BIBLIOTECA www.museogalileo.it/biblioteca.html BIBLIOTECA DI GALILEO La ricostruzione dell’inventario della biblioteca di Galileo rappresenta uno strumento essenziale per comprendere appieno i riferimenti culturali del grande scienziato toscano. Già alla fine dell’Ottocento, Antonio Favaro, curatore dell’Edizione Nazionale delle Opere galileiane, individuò più di 500 opere appartenute a Galileo (cfr. A. Favaro, La libreria di Galileo Galilei, in «Bullettino di bibliografia e di storia delle scienze matematiche e fisiche», XIX, 1886, p. 219-293 e successive appendici del 1887 e 1896). Il catalogo di Favaro si è arricchito di ulteriori segnalazioni bibliografiche, frutto di recenti ricerche sul tema compiute da Michele Camerota (La biblioteca di Galileo: alcune integrazioni e aggiunte desunte dal carteggio, in Biblioteche filosofiche private in età moderna e contemporanea. Firenze : Le Lettere, 2010, p. 81-95) e Crystal Hall (Galileo's library reconsidered. « Galilaeana», a. 12 (2015), p. 29-82). Si è giunti così all’identificazione di un totale di 600 volumi che furono certamente nella disponibilità di Galileo. Alcune delle edizioni qui registrate sono possedute anche dalla Biblioteca del Museo Galileo, altre sono accessibili in versione digitale nella Banca dati cumulativa del Museo Galileo alla url: www.museogalileo.it/bancadaticumulativa.html GALILEO’s LIBRARY The reconstruction of the inventory of Galileo' s library represents an essential tool to fully understand the cultural references of the great Tuscan scientist. By the end of the nineteenth century, Antonio Favaro, curator of the National Edition of the Opere by Galileo, found more than 500 works belonging to the private library of the scientist (cfr. -

I Had to Fight with the Painters, Master Carpenters

‘I had to fight with the painters, master carpenters, actors, musicians and the dancers’: Rehearsals, performance problems and audience reaction in Renaissance spectacles Jennifer Nevile Early Dance Circle Annual Lecture, 21 February 2021 In 1513 Castiglione wrote about the difficulties he was having during the rehearsals for a production at Urbino. [the intermedio] about the battles was unfortunately true - to our disgrace. … [The intermedi] were made very much in a hurry, and I had to fight with the painters, the master carpenters, the actors, musicians and the dancers.1 Unfortunately, we do not know exactly what caused the arguments between Castiglione and all the personnel involved in this production, and neither do we know how these difficulties were resolved. But Castiglione’s letter reminds us that then, as now, not everything went as smoothly as those in charge would have hoped for. In spite of the many glowing reports as to the success of theatrical spectacles in early modern Europe, the wonder and amazement of the audience, the brilliance of the glittering costumes, the quantity of jewels and precious stones worn by the performers and the virtuosity of the dancing, problems were encountered during production and the performance. It is this aspect of Renaissance spectacles that is the focus of today’s lecture. I will begin with a discussion of the desire for a successful outcome, and what efforts went into achieving this aim, before moving to an examination of what disasters did occur, from audience over-crowding and noise, stage-fright of the performers, properties being too big to fit through the door into the hall in which the performance was taking place, to more serious catastrophes such as a fire during a performance. -

Die Mythologischen Musikdramen Des Frühen 17. Jahrhunderts: Eine Gattungshistorische Untersuchung

Die mythologischen Musikdramen des frühen 17. Jahrhunderts: eine gattungshistorische Untersuchung Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doctor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freie Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Alessandra Origgi Berlin 2018 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Huss (Freie Universität Berlin) Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Franz Penzenstadler (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen) Tag der Disputation: 18.07.2018 Danksagung Mein Dank gilt vor allem meinen beiden Betreuern, Herrn Prof. Dr. Bernhard Huss (Freie Universität Berlin), der mich stets mit seinen Anregungen unterstützt und mir die Möglichkeit gegeben hat, in einem menschlich und intellektuell anregenden Arbeitsbereich zu arbeiten, und Herrn Prof. Dr. Franz Penzenstadler (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen), der das Promotionsprojekt in meinen Tübinger Jahren angeregt und auch nach meinem Wechsel nach Berlin fachkundig und engagiert begleitet hat. Für mannigfaltige administrative und menschliche Hilfe in all den Berliner Jahren bin ich Kerstin Gesche zu besonderem Dank verpflichtet. Für die fachliche Hilfe und die freundschaftlichen Gespräche danke ich meinen Kolleginnen und Kollegen sowie den Teilnehmenden des von Professor Huss geleiteten Forschungskolloquiums an der Freien Universität Berlin: insbesondere meinen früheren Kolleginnen Maraike Di Domenica und Alice Spinelli, weiterhin Siria De Francesco, Dr. Federico Di Santo, Dr. Maddalena Graziano, Dr. Tatiana Korneeva, Thea Santangelo und Dr. Selene Vatteroni. -

Annual Report 1975

mm ; mm .... : ' ^: NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 1975 Property of the National Gallery of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D C. 20565. Copyright © 1976, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art Inside cover photograph by Robert C. Lautman; photograph on page 91 by Helen Marcus; all other photographs by the photographic staff of the National Gallery of Art. Frontispiece: Bronze Galloping Horse, Han Dynasty, courtesy the People's Republic of China CONTENTS 6 ORGANIZATION 9 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 20 DONORS AND ACQUISITIONS 47 LENDERS 50 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 50 Extension Program Development and Services 51 Art and Man 51 Loans of Works of Art 61 EDUCATIONAL SERVICES 61 Lectures, Tours, Texts, Films 64 Art Information Service 65 DEPARTMENTAL REPORTS 65 Curatorial Departments 66 Graphic Arts 67 Library 68 Photographic Archives 69 Conservation Treatment and Research 72 Editor's Office 72 Exhibitions and Loans 74 Registrar's Office 74 Installation and Design 75 Photographic Laboratory Services 76 STAFF ACTIVITIES 82 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH, AND SCHOLARLY PUBLICATIONS 86 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 89 PUBLICATIONS SERVICE 90 BUILDING MAINTENANCE, SECURITY AND ATTENDANCE 92 APPROPRIATIONS 93 EAST BUILDING 94 ROSTER OF EMPLOYEES ORGANIZATION The 38th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects another year of continuing growth and change. Although formally established by Congress as a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery is an autonomous and separately administered organization and is gov- erned by its own Board of Trustees. -

Le Fou Et La Magicienne Réécritures De L'arioste À L

AIX MARSEILLE UNIVERSITÉ ÉCOLE DOCTORALE 355 ESPACES, CULTURES ET SOCIÉTÉS CENTRE AIXOIS D’ÉTUDES ROMANES – EA 854 DOCTORAT EN ÉTUDES ITALIENNES Fanny EOUZAN LE FOU ET LA MAGICIENNE RÉÉCRITURES DE L’ARIOSTE À L’OPÉRA (1625-1796) Thèse dirigée par Mme Perle ABBRUGIATI Soutenue le 17 juin 2013 Jury : Mme Perle ABBRUGIATI, Professeur, Aix Marseille Université Mme Brigitte URBANI, Professeur, Aix Marseille Université M. Jean-François LATTARICO, Professeur, Université Lyon 3 – Jean Moulin M. Camillo FAVERZANI, Maître de conférences HDR, Université Paris 8 – Saint Denis M. Sergio ZATTI, Professore, Università di Pisa Je remercie chaleureusement L’École doctorale 355 Espaces, Cultures et Sociétés de l’Aix Marseille Université de m’avoir permis d’achever cette thèse. La Fondazione Cini de Venise de m’avoir accueillie pour un séjour de recherches. Le personnel de la Bibliothèque nationale de Turin de m’avoir aidée dans mes recherches sur les partitions de Vivaldi. Les membres du jury d’avoir accepté de lire mon travail. Ma directrice de recherches, Mme Perle Abbrugiati, pour son soutien indéfectible et ses précieux conseils. Mon compagnon, mes enfants, mes parents et mes beaux-parents, mes amis et mes collègues, pour leurs encouragements et leur compréhension pendant cette longue et difficile période. SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION 1 I. Origine des réécritures : l’Arioste 2 1. Les personnages 4 2. L’Arioste et les arts 9 3. De l’Arioste au Tasse : le genre chevaleresque, ses réécritures littéraires et sa réception 16 II. L’Arioste à l’opéra 25 Avertissement : choix de traductions et citations 35 Description du corpus : le sort des personnages après l’Arioste 37 PREMIÈRE PARTIE : REPÉRAGES, LA PÉRÉGRINATION DES PERSONNAGES, REFLET DE LA FORTUNE DE L’ARIOSTE ET MARQUEUR DE L’HISTOIRE DE L’OPÉRA 45 I. -

Challenging Male Authored Poetry: Margherita Costa's Marinist Lyrics

Challenging Male Authored Poetry: Margherita Costa’s Marinist Lyrics (1638–1639) Julie Louise Robarts ORCID iD 0000-0002-1055-3974 Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2019 School of Languages and Linguistics The University of Melbourne Abstract: Margherita Costa (c.1600–c.1664) authored fourteen books of prose, poetry and theatre that were published between 1630 and 1654. This is the largest printed corpus of texts authored by any woman in early modern Europe. Costa was also a virtuosa singer, performing opera and chamber music in courts and theatres first in Rome, where she was born, and in Florence, Paris, Savoy, Venice, and possibly Brunswick. Her dedicatees and literary patrons were the elite of these courts. This thesis is the first detailed study of Costa as a lyric poet, and of her early works — an enormous production of over 1046 quarto pages of poetry, and 325 pages of love letters, published in four books between 1638 and 1639: La chitarra, Il violino, Lo stipo and Lettere amorose. While archival evidence of Costa’s writing and life is scarce due to her itinerant lifestyle, her published books, and the poetic production of the male literary networks who supported her, provide a rich resource for textual, paratextual and intertextual analysis on which the findings of this study are based. This thesis reveals the role played by Costa in mid-century Marinist poetry and culture. This study identifies the strategies through which Costa opened a space for herself as an author of sensual, comic and grotesque poetry and prose in Marinist and libertine circles in Rome, Florence and Venice. -

The Fowler Collection of Early Architectural Books from Johns Hopkins University Reel Listing

Works of the Master Architects: The Fowler Collection of Early Architectural Books from Johns Hopkins University Reel Listing Accolti, Pietro (1455-1572). Alberti, Leon Battista (1404-1472). Lo Inganno De Gl'Occhi, Prospettiva Pratica Di [leaf 2 recto] Leonis Baptiste Alberti De Re Pietro Accolti…[2 lines]. Aedificatoria Incipit Lege Feliciter. In Firenze, Appresso Pietro Cecconcelli. 1625 Florentiæ accuratissime impressum opera Magistri Trattato In Acconcio Della Pittvra. [Engraved Nicolai Laurentii Alamani: Anno salutis Millesimo vignette]; Folio. 84 leaves. [i-xii], 1-152 [153-156] p. octuagesimo quinto:quarto Kalendas Ianuarias. 1485 including woodcut diagrams in text. Woodcut head- [Colophon] Lavs Deo Honor Et Gloria. Leonis and tailpieces. 30.3 cm. 11 9/16 in.; Contents: p. [i]: Baptistae Alberti Florentini Viri Clarissimi de re title page; p. [ii]: blank; p. [iii]: dedication to Aedificatoria opus elegãtissi mu et qnãmaxime utile; Cardinal Carlo de Medici; p. [iv]: blank; p. [v-vii]: Folio. 204 leaves. [1-204] leaves. 34 lines to a page. dedicatory verses to Giovambatista Strozzi, 27 cm. 10 5/8 in.; Contents: leaf [1] recto: blank; leaf Alessandro Adimari and Andrea Salvadori; p. [viii- [1] verso: Politian's dedication to Lorenzo de Medici; xii]: table of contents; p. 1-2: preface; p. 3-152: text, leaf [2] recto-leaf [203] verso: Alberti's preface and Part I-III, including woodcut diagrams; p. [153-154]: text of Book I-X, ending with colophon; leaf [204] full-page woodcut illustrations; p. [155]: woodcut recto: Baptista siculus in auctoris psona Ad printer's device above register; p. [156]: blank; Notes: lectorem...; leaf [204] verso: register; Notes: First First edition. -

Books & Prints from the Collection of Arthur

BOOKS & PRINTS FROM THE COLLECTION OF ARTHUR & CHARLOTTE VERSHBOW RIVERRUN BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS CATALOGUE TWO no. 20 2 BOOKS & PRINTS FROM THE COLLECTION OF ARTHUR & CHARLOTTE VERSHBOW The Middle Ages & The Renaissance (nos. 1-33) The Baroque & The Rococo Periods (nos. 34-93) The Neoclassical, Romantic & Modern Movements (nos. 94-123) RIVERRUN BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS CATALOGUE TWO The Middle Ages & The Renaissance Purchased, completed, and illuminated by Denis Faucher 1 BOOK OF HOURS, use of Rome, in Latin and French. ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT ON VELLUM. [West-central France, late-15th century and southern France circa 1550]. This remarkable manuscript was purchased, completed and illuminated by Denis Faucher (1487-1562), and is made up of two distinct components: the frst part, pages 1-318, is a Book of Hours written in the 15th century, while pages 320-386 were added around the middle of the 16th century. With, possibly, a few minor exceptions the entire manuscript was illuminated at the later date. The presence of Sts. Leodegar and Radegund in the Litany may indicate that the 15th-century unilluminated manuscript was intended for Poitiers (Vienne). Illumination: The historian Vincentius Barrali drew attention to Faucher’s artistic skill and wrote, “among the foremost works of art of the aforementioned Denis is a book of hours written and delicately adorned with wondrous paintings by Denis’ own hand.” He goes on to quote the note dated 9 April 1554 of the present manuscript. It is quite evident that the principal portion of the manuscript was written in the 15th-century and acquired by Faucher in an unillustrated and undecorated state. -

Jacques Callot and the Baroque Print, June 17, 2011-November 6, 2011

Jacques Callot and the Baroque Print, June 17, 2011-November 6, 2011 One of the most prolific and versatile graphic artists in Western art history, the French printmaker Jacques Callot created over 1,400 prints by the time he died in 1635 at the age of forty-three. With subjects ranging from the frivolous festivals of princes to the grim consequences of war, Callot’s mixture of reality and fanciful imagination inspired artists from Rembrandt van Rijn in his own era to Francisco de Goya two hundred years later. In these galleries, Callot’s works are shown next to those of his contemporaries to gain a deeper understanding of his influence. Born into a noble family in 1592 in Nancy in the Duchy of Lorraine (now France), Callot traveled to Rome at the age of sixteen to learn printmaking. By 1614, he was in Florence working for Cosimo II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. After the death of the Grand Duke in 1621, Callot returned to Nancy, where he entered the service of the dukes of Lorraine and made prints for other European monarchs and the Parisian publisher Israël Henriet. Callot perfected the stepped etching technique, which consisted of exposing copperplates to multiple acid baths while shielding certain areas from the chemical with a hard, waxy ground (see the book illustration in the adjoining gallery). This process contributed to different depths of etched lines and thus striking light and spatial qualities when the plate was inked and printed. Callot may have invented the échoppe, a tool with a curved tip that he used to sweep through the hard ground to create curved and swelled lines in imitation of engraving.