Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wartburgmobil – Vorstellung Fahrplanerverbesserungen Zum 01.05.2020

Wartburgmobil – Vorstellung Fahrplanerverbesserungen zum 01.05.2020 Im Rahmen der Verwaltungsratssitzung unseres Unternehmens im Herbst 2019 wurde festgestellt, dass sich z.B. die Verbindung Eisenach – Bad Liebenstein über Glasbach nicht bewährt hat. Zudem war dadurch keine direkte Verbindung Eisenach – Inselsberg mehr möglich. Ebenso kam vermehrt der Wunsch, auch nach 17:00Uhr noch eine Verbindung nach Bad Liebenstein von Eisenach aus anzubieten. Weiterhin kamen Wünsche aus Barchfeld direkt nach Eisenach fahren zu können und aus dem Raum südliches Werratal/Rhön fehlende Umsteigebeziehungen Richtung Bad Liebenstein. Aus Bad Liebenstein und Barchfeld hat sich zudem der Wunsch ergeben Verbindungen in den Landkreis Schmalkalden-Meiningen herzustellen. Alle diese Wünsche, Anregungen und Bitten haben wir in den letzten Monaten gesammelt und ausgewertet. Zusätzlich wurden Gespräche mit Touristikern und Bürgermeistern geführt. Daraus ist nun folgendes Konzept entstanden, das wir zum 1.5.2020 umsetzen: 1) Ordnung der Liniennummern Nördlich des Rennsteigs: es bleibt bei 14x-Liniennummern o 140 Eisenach – Ruhla – Bad Liebenstein o 142 Eisenach – Bad Tabarz o 143 Eisenach – Mosbach o 144 Kittelsthal – Ruhla Südlich des Rennsteigs: die Liniennummer ändern sich auf 19x o 190 Eisenach – Hohe Sonne – Moorgrund – Bad Liebenstein – Barchfeld – Bad Salzungen neue Linie o 191 Bad Salzungen – Möhra Liniennummer unverändert o 192 Bad Liebenstein – Möhra Umbenennung: alt 141 o 195 Eisenach – Hohe Sonne – Moorgrund – Bad Liebenstein Umbenennung: alt 145 o 196 -

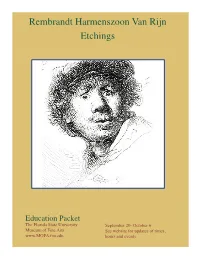

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

Programmation De France Médias Monde Format

Mardi 14 mars 2017 RFI ET FRANCE 24 MOBILISEES A L’OCCASION DE LA JOURNEE DE LA LANGUE FRANCAISE DANS LES MEDIAS Lundi 20 mars 2017 Le 20 mars, RFI et France 24 s’associent à la troisième édition de la « Journée de la langue française dans les médias », initiée par le CSA, dans le cadre de la « Semaine de la langue française et de la Francophonie ». A cette occasion, RFI délocalise son antenne à l’Académie française et propose une programmation spéciale avec notamment l’annonce dans l’émission « La danse des mots » des résultats de son jeu « Speakons français » qui invitait, cette année, les auditeurs et internautes à trouver des équivalents français à des anglicismes courants utilisés dans le monde du sport. France 24 consacre reportages et entretiens à l’enjeu de la qualité de la langue française employée dans les médias qui, plus qu’un simple outil de communication, est une manière de comprendre le monde en le nommant. Les rédactions en langues étrangères de RFI sont également mobilisées, notamment à travers leurs émissions bilingues, qui invitent les auditeurs à se familiariser à la langue française. Celles-ci viennent appuyer le travail du service RFI Langue française, qui à travers le site RFI SAVOIRS met à disposition du grand public et des professionnels de l’éducation des ressources et outils pour apprendre le français et comprendre le monde en français. Enfin, France 24 diffusera, du 20 au 26 mars, les spots de sensibilisation « Dites-le en français » , réalisés par les équipes de France Médias Monde avec France Télévisions et TV5MONDE. -

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] THE MORGAN HOSTS MAJOR EXHIBITION OF MASTER DRAWINGS FROM MUNICH’S FAMED STAATLICHE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG SHOW INCLUDES WORKS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE MODERN PERIOD AND MARKS THE FIRST TIME THE GRAPHISCHE SAMMLUNG HAS LENT SUCH AN IMPORTANT GROUP OF DRAWINGS TO AN AMERICAN MUSEUM Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich October 12, 2012–January 6, 2013 **Press Preview: Thursday, October 11, 10 a.m. until 11:30 a.m.** RSVP: (212) 590-0393, [email protected] New York, NY, August 25, 2012—This fall, The Morgan Library & Museum will host an extraordinary exhibition of rarely- seen master drawings from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich, one of Europe’s most distinguished drawings collections. On view October 12, 2012– January 6, 2013, Dürer to de Kooning: 100 Master Drawings from Munich marks the first time such a comprehensive and prestigious selection of works has been lent to a single exhibition. Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789–1869) Italia and Germania, 1815–28 Dürer to de Kooning was conceived in Inv. 2001:12 Z © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München exchange for a show of one hundred drawings that the Morgan sent to Munich in celebration of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung’s 250th anniversary in 2008. The Morgan’s organizing curators were granted unprecedented access to the Graphische Sammlung’s vast holdings, ultimately choosing one hundred masterworks that represent the breadth, depth, and vitality of the collection. The exhibition includes drawings by Italian, German, French, Dutch, and Flemish artists of the Renaissance and baroque periods; German draftsmen of the nineteenth century; and an international contingent of modern and contemporary draftsmen. -

How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia

— Early draft. Please do not quote, cite, or redistribute without written permission of the authors. — How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia After 1815∗ Thilo R. Huningy and Nikolaus Wolfz Abstract We analyze the formation oft he German Zollverein as an example how geography can shape institutional change. We show how the redrawing of the European map at the Congress of Vienna—notably Prussia’s control over the Rhineland and Westphalia—affected the incentives for policymakers to cooperate. The new borders were not endogenous. They were at odds with the strategy of Prussia, but followed from Britain’s intervention at Vienna regarding the Polish-Saxon question. For many small German states, the resulting borders changed the trade-off between the benefits from cooperation with Prussia and the costs of losing political control. Based on GIS data on Central Europe for 1818–1854 we estimate a simple model of the incentives to join an existing customs union. The model can explain the sequence of states joining the Prussian Zollverein extremely well. Moreover we run a counterfactual exercise: if Prussia would have succeeded with her strategy to gain the entire Kingdom of Saxony instead of the western provinces, the Zollverein would not have formed. We conclude that geography can shape institutional change. To put it different, as collateral damage to her intervention at Vienna,”’Britain unified Germany”’. JEL Codes: C31, F13, N73 ∗We would like to thank Robert C. Allen, Nicholas Crafts, Theresa Gutberlet, Theocharis N. Grigoriadis, Ulas Karakoc, Daniel Kreßner, Stelios Michalopoulos, Klaus Desmet, Florian Ploeckl, Kevin H. -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

Eisenach 2 Lage in Mitteldeutschland 3 Übersicht 4 Antragstellung 5

PR O D U K TIO N SZEN TR U M EISEN A CH IN H A LT Produktionszentrum Eisenach 2 Lage in Mitteldeutschland 3 Übersicht 4 Antragstellung 5 Adressen Locations und Dienstleister 6 Immobilien, Hallen und Produktionsbüros 6 Unterkünfte und Hotels 6 Gastroverzeichnis 6 Notdienste und Gesundheitsversorgung 6 Energie, Wasser, Abwasser und Abfall 7 Verkehrsinformationen 7 Kinos und Theater 7 Regionale Pressekontakte 8 Referenzprojekte 10 Kontakt & Impressum 11 Seite 1 von 11 PR O D U K TIO N SZEN TR U M EISEN A CH OBERBÜRGERMEISTERIN Katja Wolf (Die Linke) Weltweite Bekanntheit verdankt die Stadt Eisenach ihrem Wahrzeichen, GEOGRAFISCHE LAGE 10° 19` östliche Länge der Wartburg. Der Reformator Martin Luther übersetzte hier das Neue 50° 59` nördliche Breite Testament erstmals in die deutsche Sprache. Im 19. Jahrhundert traffen FLÄCHE DES STADTGEBIETES 104 km2 sich Studenten und Professoren an dem historischen Ort um für einen EINWOHNER 43 000 deutschen Nationalstaat einzutreten und einer der beliebtesten Pkw in der ENTFERNUNGEN Leipzig 190 km (2:00 h) DDR trug den Namen des geschichtsträchtigen Ortes. Die Frankfurt/M. 200 km (2:00 h) Fahrzeugproduktion ist bis heute ein wichtiger Erwerbszweig am Standort Berlin 360 km (3:30h) Eisenach. V E R K E H R S A N B I N D U N G Das Stadtbild wird von Bauten des 15. bis 20. Jahrhunderts geprägt,ältere AUTOBAHN A4 Bausubstanz ist oftmals überformt oder umgebaut. Von herausragender BAHN ICE, IC, RB architektonischer Bedeutung sind vor allem die Villen, die seit dem 19. ÖPNV KVG Eisenach mbH, Jahrhundert unterhalb der Wartburg entstanden. In spätklassizistischen www.kvg-eisenach.de Formen bis hin zum Bauhausstil bilden sie heute eines der größten noch Verkehrsgesellschaft erhaltenen Villengebiete in Deutschland mit rund 450 Häusern. -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Renaissance and Baroque Europe Author(S): Keith Christiansen, Nadine M

Renaissance and Baroque Europe Author(s): Keith Christiansen, Nadine M. Orenstein, William M. Griswold, Suzanne Boorsch, Clare Vincent, Donald J. LaRocca, Helen B. Mules, Walter Liedrke, Alice Zrebiec, Stuart W. Phyrr and Olga Raggio Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 52, No. 2, Recent Acquisitions: A Selection 1993-1994 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 20-35 Published by: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3258872 . Accessed: 02/06/2014 14:36 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.140.1.131 on Mon, 2 Jun 2014 14:36:29 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE Agostino Carracci Among the most innovativeworks of the late seem to support an attribution to his brother Italian (Bologna),1557-1602 sixteenth century are a small group of infor- Agostino, and, indeed, a composition of this or Annibale Carracci mal easel paintings treatingeveryday themes subject attributed to Agostino is listed in a Italian (Bologna),I560o-609 produced in the academy of the Carracci I680 inventory of the Farnesecollections in Two Children Teasinga Cat family in Bologna. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

Annual Report 1975

mm ; mm .... : ' ^: NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 1975 Property of the National Gallery of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D C. 20565. Copyright © 1976, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art Inside cover photograph by Robert C. Lautman; photograph on page 91 by Helen Marcus; all other photographs by the photographic staff of the National Gallery of Art. Frontispiece: Bronze Galloping Horse, Han Dynasty, courtesy the People's Republic of China CONTENTS 6 ORGANIZATION 9 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 20 DONORS AND ACQUISITIONS 47 LENDERS 50 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 50 Extension Program Development and Services 51 Art and Man 51 Loans of Works of Art 61 EDUCATIONAL SERVICES 61 Lectures, Tours, Texts, Films 64 Art Information Service 65 DEPARTMENTAL REPORTS 65 Curatorial Departments 66 Graphic Arts 67 Library 68 Photographic Archives 69 Conservation Treatment and Research 72 Editor's Office 72 Exhibitions and Loans 74 Registrar's Office 74 Installation and Design 75 Photographic Laboratory Services 76 STAFF ACTIVITIES 82 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH, AND SCHOLARLY PUBLICATIONS 86 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 89 PUBLICATIONS SERVICE 90 BUILDING MAINTENANCE, SECURITY AND ATTENDANCE 92 APPROPRIATIONS 93 EAST BUILDING 94 ROSTER OF EMPLOYEES ORGANIZATION The 38th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects another year of continuing growth and change. Although formally established by Congress as a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery is an autonomous and separately administered organization and is gov- erned by its own Board of Trustees.