WHY NEMO MATTERS: ALTRUISM in AMERICAN ANIMATION by DAVID

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Stereotypes: Th Movies-A Special Reference to And

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ResearchResearch Larbi Ben M’h idi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Racism and Stereotypes: The Image of the Other in Disney’s Movies-A Special Reference to Aladdin , Dumbo and The Lion King A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: Abed Khaoula Board of Examiners Supervisor: Hafsa Naima Examiner: Stiti Rinad 2015-2016 Dedication To the best parents on earth Ouiza and Mourad To the most adorable sisters Shayma, Imène, Kenza and Abir To my best friend Doudou with love i Acknowledgements First of all,I would like to thank ‘A llah’ who guides and gives me the courage and Patience for conducting this research.. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my supervisor Miss Hafsa Naima who traced the path for this dissertation. This work would have never existed without her guidance and help. Special thanks to my examiner Miss Stiti Rinad who accepted to evaluate my work. In a more personal vein I would like to thank my mother thousand and one thanks for her patience and unconditional support that facilitated the completion of my graduate work. Last but not least, I acknowledge the help of my generous teacher Mr. Bouri who believed in me and lifted up my spirits. Thank you for everyone who believed in me. ii ا ا أن اوات ا اد ر ر دة اطل , د ه اوات ا . -

Disney Syllabus 12

WS 325: Disney: Gender, Race, and Empire Women Studies Oregon State University Fall 2012 Thurs., 2:00-3:20 WLKN 231 (3 credits) Dr. Patti Duncan 266 Waldo Hall Office Hours: Mon., 2:00-3:30 and by appt email: [email protected] Graduate Teaching Assistant: Chelsea Whitlow [OFFICE LOCATION] Office Hours: Mon./Wed., 9:30-11:00 email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION Introduces key themes and critical frameworks in feminist film theories and criticism, focused on recent animated Disney films. Explores constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in these representations. (H) (Bacc Core Course) PREREQUISITES: None, but a previous WS course is helpful. COURSE DESCRIPTION In this discussion-oriented course, students will explore constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in the recent animated films of Walt Disney. By examining the content of several Disney films created within particular historical and cultural contexts, we will develop and expand our understanding of the cultural productions, meanings, and 1 intersections of racism, sexism, classism, colonialism, and imperialism. We will explore these issues in relation to Disney’s representations of concepts such as love, sex, family, violence, money, individualism, and freedom. Also, students will be introduced to concepts in feminist film theory and criticism, and will develop analyses of the politics of representation. Hybrid Course This is a hybrid course, where approximately 50% of the course will take place in a traditional face-to-face classroom and 50% will be delivered via Blackboard, your online learning community, where you will interact with your classmates and with the instructor. -

The Lion King Audition Monologues

Audition Monologues Choose ONE of the monologues. This is a general call; the monologue you choose does not affect how you will be cast in the show. We are listening to the voice, character development, and delivery no matter what monologue you choose. SCAR Mufasa’s death was a terrible tragedy; but to lose Simba, who had barely begun to live... For me it is a deep personal loss. So, it is with a heavy heart that I assume the throne. Yet, out of the ashes of this tragedy, we shall rise to greet the dawning of a new era... in which lion and hyena come together, in a great and glorious future! MUFASA Look Simba. Everything the light touches is our kingdom. A king's time as ruler rises and falls like the sun. One day, Simba, the sun will set on my time here - and will rise with you as the new king. Everything exists in a delicate balance. As king, you need to understand that balance, and respect for all creatures-- Everything is connected in the great Circle of Life. YOUNG SIMBA Hey Uncle Scar, guess what! I'm going to be king of Pride Rock. My Dad just showed me the whole kingdom, and I'm going to rule it all. Heh heh. Hey, Uncle Scar? When I'm king, what will that make you? {beat} YOUNG NALA Simba, So, where is it? Better not be any place lame! The waterhole? What’s so great about the waterhole? Ohhhhh….. Uh, Mom, can I go with Simba? Pleeeez? Yay!!! So, where’re we really goin’? An elephant graveyard? Wow! So how’re we gonna ditch the dodo? ZAZU (to Simba) You can’t fire me. -

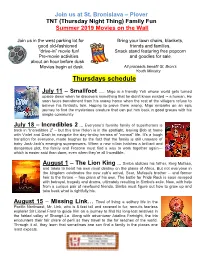

Thursdays Schedule

Join us at St. Bronislava – Plover TNT (Thursday Night Thing) Family Fun Summer 2019 Movies on the Wall Join us in the west parking lot for Bring your lawn chairs, blankets, good old-fashioned friends and families. “drive-in” movie fun! Snack stand featuring free popcorn Pre-movie activities and goodies for sale. about an hour before dusk. Movies begin at dusk. All proceeds benefit St. Bron’s Youth Ministry Thursdays schedule July 11 – Smallfoot … Migo is a friendly Yeti whose world gets turned upside down when he discovers something that he didn't know existed -- a human. He soon faces banishment from his snowy home when the rest of the villagers refuse to believe his fantastic tale. Hoping to prove them wrong, Migo embarks on an epic journey to find the mysterious creature that can put him back in good graces with his simple community July 18 – Incredibles 2 … Everyone’s favorite family of superheroes is back in “Incredibles 2” – but this time Helen is in the spotlight, leaving Bob at home with Violet and Dash to navigate the day-to-day heroics of “normal” life. It’s a tough transition for everyone, made tougher by the fact that the family is still unaware of baby Jack-Jack’s emerging superpowers. When a new villain hatches a brilliant and dangerous plot, the family and Frozone must find a way to work together again— which is easier said than done, even when they’re all Incredible. August 1 – The Lion King … Simba idolizes his father, King Mufasa, and takes to heart his own royal destiny on the plains of Africa. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Disney•Pixar's “Finding Dory”

Educator’s Guide GRADES 2-6 Created in partnership with the Educational Team isney•Pixar’s “Finding Dory” welcomes back to the big convinced his biological sonar skills are on the fritz; and Dscreen everyone’s favorite forgetful blue tang Dory Destiny (voice of Kaitlin Olson), a nearsighted whale shark. (voice of Ellen DeGeneres), who’s living happily in the reef Deftly navigating the complex inner workings of the MLI, with Marlin (voice of Albert Brooks) and Nemo (voice Dory and her friends discover the magic within their flaws, of Hayden Rolence). When Dory suddenly remembers friendships and family. that she has a family out there who may be looking for Directed by Andrew Stanton (“Finding Nemo,” “WALL•E”), her, the trio takes off on a life-changing adventure across co-directed by Angus MacLane (“Toy Story OF TERROR!”), the ocean to California’s prestigious Marine Life Institute and produced by Lindsey Collins (co-producer “WALL•E”), (MLI), a rehabilitation center and aquarium. In an effort to Disney•Pixar’s “Finding Dory” swims home on Digital find her mom (voice of Diane Keaton) and dad (voice of HD October 25 and on Blu-ray™ November 15. For Eugene Levy), Dory enlists the help of three of the MLI’s more information, like us on Facebook, https://www. most intriguing residents: Hank (voice of Ed O’Neill), a facebook.com/PixarFindingDory, and follow us on Twitter, cantankerous octopus who frequently gives employees https://twitter.com/findingdory and Instagram, https:// the slip; Bailey (voice of Ty Burrell), a beluga whale who is instagram.com/DisneyPixar. -

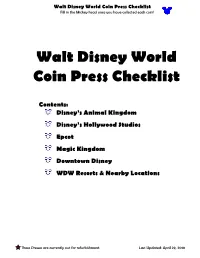

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey Head Once You Have Collected Each Coin!

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Contents: Disney’s Animal Kingdom Disney’s Hollywood Studios Epcot Magic Kingdom Downtown Disney WDW Resorts & Nearby Locations These Presses are currently out for refurbishment. Last Updated: April 29, 2010 Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Out of the Wild #1 Lion King 5 of 7, Rafiki Celebrate Culture South Africa Tarzan 7 of 8, Jane & Tarzan The Outpost Shop #1 Penny Presses Jungle Book 6 of 6, Share Khan Beastly Bazaar Safari Minnie Mouse Tarzan 4 of 8, Tantor Safari Pluto Lion King 3 of 7, Hula Timon Safari Goofy The Outpost Shop #2 Stink Bug Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #1 Tarzan 8 of 8, Jane Iguanodon Lion King 1 of 7, Simba Camtaurus Alioramus Rainforest Café #1 Hot Air Balloon, Orlando, FL Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #2 Mockingbird, Florida State Bird Tarzan 3 of 8, Terk Crab w/ Sunglasses, Orlando, FL Mickey with Fossil Alligator, Orlando, FL Lion King 6 of 7, Scar Restaurantosaurus #1 Dawa Bar Styracosaurus Lion Saltasaurus Hippopotamus Ankylosaurus Rhino Restaurantosaurus #2 Duka La Filimu #1 Tarzan 1 of 8, Tarzan & Jane Safari Mickey Duckosaurus Donald Safari Donald Dinosaur Skeleton Safari Goofy Wildlife Express Train Station #1 Duka La Filimu #2 Tarzan 2 of 8, Swinging Tarzan Safari Minnie Tarzan 5 of 8, Professor Safari Pooh Lion King 4 of 7, Pumba Safari Tigger Island Mercantile #1 Festival of The Lion -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

Disneyland® Park

There’s magic to be found everywhere at The Happiest Place on Earth! Featuring two amazing Theme Parks—Disneyland® Park and Disney California Adventure® Park—plus three Disneyland® Resort Hotels and the Downtown Disney® District, the world-famous Disneyland® Resort is where Guests of all ages can discover wonder, joy and excitement around every turn. Plan enough days to experience attractions and entertainment in 1 both Parks. 5 INTERSTATE 4 5 2 3 6 Go back and forth between both Theme Parks with a Disneyland® Resort Park Hopper® 1 Disneyland® Hotel 4 Downtown Disney® District Ticket. Plus, when you buy a 3+ day ticket before you arrive, you get one Magic Morning* 2 Disney’s Paradise Pier® Hotel Disneyland® Park early admission to select experiences 5 at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the general public on select days. 3 Disney’s Grand Californian Hotel® & Spa 6 Disney California Adventure® Park *Magic Morning allows one early admission (during the duration of the Theme Park ticket or Southern California CityPASS®) to select attractions, stores, entertainment and dining locations at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the public on Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday. Each member of your travel party must have 3-day or longer Disneyland® Resort tickets. To enhance the Magic Morning experience, it is strongly recommended that Guests arrive at least one hour and 15 minutes prior to regular Park opening. Magic Morning admission is based on availability and does not operate daily. Applicable days and times of operation and all other elements including, but not limited to, operation of attractions, entertainment, stores and restaurants and appearances of Characters may vary and are subject to change without notice. -

Masculinity in Children's Film

Masculinity in Children’s Film The Academy Award Winners Author: Natalie Kauklija Supervisor: Mariah Larsson Examiner: Tommy Gustafsson Spring 2018 Film Studies Bachelor Thesis Course Code 2FV30E Abstract This study analyzes the evolution of how the male gender is portrayed in five Academy Award winning animated films, starting in the year 2002 when the category was created. Because there have been seventeen award winning films in the animated film category, and there is a limitation regarding the scope for this paper, the winner from every fourth year have been analyzed; resulting in five films. These films are: Shrek (2001), Wallace and Gromit (2005), Up (2009), Frozen (2013) and Coco (2017). The films selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the Animated Feature film category tend to be both critically and financially successful, and watched by children, young adults, and adults worldwide. How male heroes are portrayed are generally believed to affect not only young boys who are forming their identities (especially ages 6-14), but also views on gender behavioral expectations in girls. Key words Children’s Film, Masculinity Portrayals, Hegemonic Masculinity, Masculinity, Film Analysis, Gender, Men, Boys, Animated Film, Kids Film, Kids Movies, Cinema, Movies, Films, Oscars, Ceremony, Film Award, Awards. Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 Problem Statements ____________________________________________________ 2 Method and Material ____________________________________________________ -

An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kramer, Heidi Tilney, "Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films by Heidi Tilney Kramer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Payne, Ph. D. Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 26, 2013 Keywords: children, animation, violence, nationalism, militarism Copyright © 2013, Heidi Tilney Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................ii Chapter One: Monsters Under -

White Savior, Savagery, & Criminality in Zootopia

White Savior, Savagery, & Criminality in Zootopia Nagata 1 A White Savior, Savagery, and Criminality in the City of “Multitudinous Opportunity” in Zootopia Matthew Nagata California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo White Savior, Savagery, & Criminality in Zootopia Nagata 2 Everyone comes to Zootopia thinking they can be anything they want, well you can’t. You can only be what you are. (Nick Wilde, 2016, Zootopia) The Disney company is distinguished for being the frontrunner in profit and popularity for animated movies worldwide. In 2016, Walt Disney Animation Studios released a film called Zootopia (Spencer, 2016). Not only did Zootopia win an Academy Award for best animated feature film, but the film also received a high score of 98% from the popular online movie review website RottenTomatoes, and made more than three hundred million dollars at the box- office (RottenTomatoes, 2016). The animated film is such a success that the Shanghai Disneyland theme park is getting its own Zootopia-land, which will be a replica of the city from the film that people will be able to walk-through and experience (Frater 2019). The Case of the Missing Animals Zootopia follows a small bunny named Judy Hopps who becomes the first bunny cop in Zootopia. Zootopia is a city in which animals of prey and those who are predators are able to put aside their hunting differences, and live together in harmony, until various predators start to go missing and become in touch with their more savage, “primal,” and violent instincts. Judy Hopps, along with a shady fox named Nick Wilde, take on the case of the missing animals.