An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Stereotypes: Th Movies-A Special Reference to And

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ResearchResearch Larbi Ben M’h idi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Racism and Stereotypes: The Image of the Other in Disney’s Movies-A Special Reference to Aladdin , Dumbo and The Lion King A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: Abed Khaoula Board of Examiners Supervisor: Hafsa Naima Examiner: Stiti Rinad 2015-2016 Dedication To the best parents on earth Ouiza and Mourad To the most adorable sisters Shayma, Imène, Kenza and Abir To my best friend Doudou with love i Acknowledgements First of all,I would like to thank ‘A llah’ who guides and gives me the courage and Patience for conducting this research.. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my supervisor Miss Hafsa Naima who traced the path for this dissertation. This work would have never existed without her guidance and help. Special thanks to my examiner Miss Stiti Rinad who accepted to evaluate my work. In a more personal vein I would like to thank my mother thousand and one thanks for her patience and unconditional support that facilitated the completion of my graduate work. Last but not least, I acknowledge the help of my generous teacher Mr. Bouri who believed in me and lifted up my spirits. Thank you for everyone who believed in me. ii ا ا أن اوات ا اد ر ر دة اطل , د ه اوات ا . -

Disney Syllabus 12

WS 325: Disney: Gender, Race, and Empire Women Studies Oregon State University Fall 2012 Thurs., 2:00-3:20 WLKN 231 (3 credits) Dr. Patti Duncan 266 Waldo Hall Office Hours: Mon., 2:00-3:30 and by appt email: [email protected] Graduate Teaching Assistant: Chelsea Whitlow [OFFICE LOCATION] Office Hours: Mon./Wed., 9:30-11:00 email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION Introduces key themes and critical frameworks in feminist film theories and criticism, focused on recent animated Disney films. Explores constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in these representations. (H) (Bacc Core Course) PREREQUISITES: None, but a previous WS course is helpful. COURSE DESCRIPTION In this discussion-oriented course, students will explore constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in the recent animated films of Walt Disney. By examining the content of several Disney films created within particular historical and cultural contexts, we will develop and expand our understanding of the cultural productions, meanings, and 1 intersections of racism, sexism, classism, colonialism, and imperialism. We will explore these issues in relation to Disney’s representations of concepts such as love, sex, family, violence, money, individualism, and freedom. Also, students will be introduced to concepts in feminist film theory and criticism, and will develop analyses of the politics of representation. Hybrid Course This is a hybrid course, where approximately 50% of the course will take place in a traditional face-to-face classroom and 50% will be delivered via Blackboard, your online learning community, where you will interact with your classmates and with the instructor. -

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017

Smith, Susan, Noel Brown, and Sam Summers. "Bibliography." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 220–232. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 20:22 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 220 B IBLIOGRAPHY A c k e r m a n , A l a n , Seeing Th ings: From Shakespeare to Pixar ( Toronto : University of Toronto Press , 2011 ). Adamson , Glen and Victoria Kelley (eds). Surface Tensions: Writings on Popular Design and Material Culture ( Manchester : Manchester University Press , 2013 ). Akers , Chelsie Lynn . ‘Th e Rise of Humour: Hollywood Increases Adult Centred Humour in Animated Children’s Films’ (unpublished Master’s thesis submitted to Brigham Young University, July 2013 ). Allison , Tanine . ‘ Blackface, Happy Feet : Th e Politics of Race in Motion Picture Animation ’, in Dan North et al. (eds), Special Eff ects: New Histories, Th eories, Contexts ( London : BFI/ Palgrave Macmillan , 2015 ), pp. 114 – 26 . A l t m a n , R i c k . Film/ Genre ( London : BFI , 1999 ). Amidi , Amid . Th e Art of Pixar: Th e Complete Colorscripts and Select Art from 25 Years of Animation ( San Francisco : Chronicle Books , 2011 ). Ansen , David . ‘ Disney’s Digital Delight ’, Newsweek , 27 November 1995 , p. 89 . Balcerzak , Scott . ‘ Andy Serkis as Actor, Body and Gorilla: Motion Capture and the Presence of Performance ’, in Jason Sperb and Scott Balcerzak (eds), Cinephilia in the Age of Digital Reproduction, Vol. -

ISSN 1820-4589 the CULTURE of POLIS, Vol. XVII (2020)

ISSN 1820-4589 THE CULTURE OF POLIS, vol. XVII (2020), special edition a journal for nurturing democratic political culture THE CULTURE OF POLIS a journal for nurturing democratic political culture Publishers: Culture – Polis Novi Sad, www.kpolisa.com; Institute of European studies Belgrade, www.ies.rs Editorial board: dr Srbobran Branković, dr Mirko Miletić, dr Aleksandar M. Petrović, dr Slaviša Orlović, dr Veljko Delibašić, dr Đorđe Stojanović, dr Milan Subotić, dr Aleksandar Gajić, dr Nebojša Petrović, dr Darko Gavrilović, dr Miloš Savin, dr Aleksandra Šuvaković, dr Milan Igrutinović. Main and accountable editor: dr Ljubiša Despotović Deputy of the main and accountable editor: dr Zoran Jevtović Assistant of the main and accountable editor: dr Željko Bjelajac Secretary of the editorial board: dr Aleksandar Matković Foreign members of the editorial board: dr Vasilis Petsinis (Grčka), dr Pol Mojzes (SAD), dr Pavel Bojko (Ruska Federacija), dr Marko Atila Hoare (Velika Britanija), dr Tatjana Tapavički - Duronjić (RS-BiH), dr Davor Pauković (Hrvatska), dr Eugen Strautiu (Rumunija) dr Daniela Blaževska (Severna Makedonija) dr Dejan Mihailović (Meksiko) Text editor: Milan Karanović Journal council: dr Živojin Đurić, predsednik; dr Vukašin Pavlović, dr Ilija Vujačić, dr Srđan Šljukić, dr Dragan Lakićević, dr Jelisaveta Todorović, dr Radoslav Gaćinović, dr Zoran Aracki, dr Nedeljko Prdić, dr Zoran Avramović, dr Srđan Milašinović, dr Joko Dragojlović, dr Marija Đorić, dr Boro Merdović, dr Aleksandar M. Filipović, dr Goran Ivančević. Printing: NS Mala knjiga + Circulation: 400. UDC 316.334.56:008 CIP – Cataloging in publication Library of Matica srpska, Novi Sad 3 КУЛТУРА полиса : часопис за неговање демократске политичке културе / главни и одговорни уредник Љубиша Деспотовић. -

Toying with Twin Peaks: Fans, Artists and Re-Playing of a Cult-Series

CULTURE / RECEPTION / CONSUMPTION TOYING WITH TWIN PEAKS: FANS, ARTISTS AND RE-PLAYING OF A CULT-SERIES KATRIINA HELJAKKA Name Katriina Heljakka and again through mimetic practices such as re-creation of Academic centre School of History, Culture and Arts Studies characters and through photoplay. Earlier studies indicate (Degree Program of) Cultural Production and Landscape that adults are showing increased interest in character toys Studies, University of Turku such as dolls, soft toys (or plush) and action figures and vari- E-mail address [email protected] ous play patterns around them (Heljakka 2013). In this essay, the focus is, on the one hand on industry-created Twin Peaks KEYWORDS merchandise, and on the other hand, fans’ creative cultivation Adult play; fandom; photoplay; re-playing; toy play; toys. and play with the series scenes and its characters. The aim is to shed light on the object practices of fans and artists and ABSTRACT how their creativity manifests in current Twin Peaks fandom. This article explores the playful dimensions of Twin Peaks The essay shows how fans of Twin Peaks have a desire not only (1990-1991) fandom by analyzing adult created toy tributes to influence how toyified versions of e.g. Dale Cooper and the to the cult series. Through a study of fans and artists “toy- Log Lady come to existence, but further, to re-play the series ing” with the characters and story worlds of Twin Peaks, I will by mimicking its narrative with toys. demonstrate how the re-playing of the series happens again 25 SERIES VOLUME I, Nº 2, WINTER 2016: 25-40 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/6589 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X PARATEXTS, FANDOMS AND THE PERSISTENCE OF TWIN PEAKS CULTURE / RECEPTION / CONSUMPTION > KATRIINA HELJAKKA TOYING WITH TWIN PEAKS: FANS, ARTISTS AND RE-PLAYING OF A CULT-SERIES FIGURE 1. -

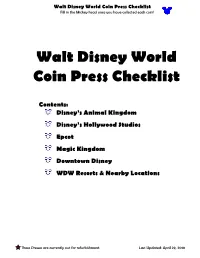

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey Head Once You Have Collected Each Coin!

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Contents: Disney’s Animal Kingdom Disney’s Hollywood Studios Epcot Magic Kingdom Downtown Disney WDW Resorts & Nearby Locations These Presses are currently out for refurbishment. Last Updated: April 29, 2010 Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Out of the Wild #1 Lion King 5 of 7, Rafiki Celebrate Culture South Africa Tarzan 7 of 8, Jane & Tarzan The Outpost Shop #1 Penny Presses Jungle Book 6 of 6, Share Khan Beastly Bazaar Safari Minnie Mouse Tarzan 4 of 8, Tantor Safari Pluto Lion King 3 of 7, Hula Timon Safari Goofy The Outpost Shop #2 Stink Bug Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #1 Tarzan 8 of 8, Jane Iguanodon Lion King 1 of 7, Simba Camtaurus Alioramus Rainforest Café #1 Hot Air Balloon, Orlando, FL Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #2 Mockingbird, Florida State Bird Tarzan 3 of 8, Terk Crab w/ Sunglasses, Orlando, FL Mickey with Fossil Alligator, Orlando, FL Lion King 6 of 7, Scar Restaurantosaurus #1 Dawa Bar Styracosaurus Lion Saltasaurus Hippopotamus Ankylosaurus Rhino Restaurantosaurus #2 Duka La Filimu #1 Tarzan 1 of 8, Tarzan & Jane Safari Mickey Duckosaurus Donald Safari Donald Dinosaur Skeleton Safari Goofy Wildlife Express Train Station #1 Duka La Filimu #2 Tarzan 2 of 8, Swinging Tarzan Safari Minnie Tarzan 5 of 8, Professor Safari Pooh Lion King 4 of 7, Pumba Safari Tigger Island Mercantile #1 Festival of The Lion -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

60 Years of Collecting Barbie®! by Christopher Varaste

60 Years of Collecting Barbie®! by Christopher Varaste Muse. Pioneer. Icon. That’s Barbie® doll, a fashion model whose stride down an endless runway inspired an entire line of quality collectibles for an astounding 60 years! An elevation of design and fashion, Barbie doll appeals to anyone interested in contemporary fashion trends. With her online presence, Barbie also serves as a major influencer. Barbie always encapsulates that intangible quality known as “style.” Under Mattel owner Ruth Handler’s influence and designer Charlotte Johnson’s tutelage, the world was first taken by surprise when Barbie was introduced at the New York Toy Fair on March 9th, 1959, along with her pink fashion booklet. Sales took off after Barbie appeared in a commercial aired during The Mickey Mouse Club™. All it took was one look and everyone wanted a Barbie doll! From the beginning, astute collectors recognized the ingenuity and detail that had gone into the doll and her wardrobe, which began to grow along with Barbie doll’s popularity. Today, those early tailored fashions are a veritable freeze frame of the era, reminiscent of Balenciaga, Schiaparelli, Givenchy and Dior. Many clever girls handled their precious Barbie dolls with care, and that eventually marked the beginning of the very first Barbie™ Fan Club in 1961, which set the stage for more clubs where Barbie™ fans could gather and make new friends. There was so much to collect! Nothing stopped Barbie from constantly evolving with hairstyles like Ponytails, Bubble Cuts, Mod hairstyles and an eclectic wardrobe that showcased the latest looks from smart suits, career outfits and go-go boots! Mattel advertisement from 1967 introducing Mod Twist ‘N Turn Barbie®. -

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure

The Use of Pleasure Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality Michel Foucault Translated from the French by Robert Hurley Vintage Books . A Division of Random House, Inc. New York The Use of Pleasure Books by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History oflnsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language) The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. ... A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes I, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 VINTAGE BOOKS EDlTlON, MARCH 1990 Translation copyright © 1985 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as L' Usage des piaisirs by Editions Gallimard. Copyright © 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in October 1985. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality. Translation of Histoire de la sexualite. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. I. An introduction-v. 2. The use of pleasure. I. Sex customs-History-Collected works. -

Pearson English Kids Readers

Teacher’s Notes Pearson EnglishTeacher’s Kids Readers Notes Pearson English Kids Readers Level 3 Suitable for: young learners who have completed up to 150 hours of study in English Type of English: American Headwords: 600 Key words: 11 (see pages 2 and 5 of these Teacher’s Notes) Key grammar: possessive ’s, Have to for obligation, quantifiers (more), simple adverbs, comparative adjectives, two clauses joined by because Summary of the story Background information The ants on Ant Island work all the time to find A Bug’s Life is a Disney-Pixar animated movie. It food for the grasshoppers who bully them. The was released in 1998 and was Pixar’s second full- ants are tired of this situation. Flik, a young ant, length movie production (the first was Toy Story). wants to help, but he is always making mistakes. It was directed by John Lasseter and written by When Flik loses all the food that the ants have Andrew Stanton. collected, he decides to go to the city to find some bigger bugs. The bigger bugs can fight the The story was inspired by Aesop’s fable, The grasshoppers and the ants can live in peace. Ant and the Grasshopper. In the fable, a starving grasshopper who spends all his time singing begs In the city, Flik meets a group of big circus bugs. some ants for food. The ants refuse as they have They agree to go back to Ant Island with him. used their time wisely to store food for winter. The circus bugs don’t understand that Flik wants The creators of A Bug’s Life thought it would be them to fight the grasshoppers – they think that he interesting to turn this idea round so that the wants them to perform for them! When the circus grasshoppers demand food from the ants. -

Evidence-Based Practices for Children Exposed to Violence: a Selection from Federal Databases

Evidence-Based Practices for Children Exposed to Violence: A Selection from Federal Databases U.S. Department of Justice U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Table of Contents • Federal Participant List • Introduction • Matrix • Service Characteristics Document • Glossary of Terms • Implementation Document Workgroup Participants Children Exposed to Violence—Evidence-based Practices Clare Anderson Deputy Commissioner Kristen Kracke, MSW Administration on Children, Youth and Families Program Specialist U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency 1250 Maryland Avenue, SW, Eighth Floor Prevention Washington, DC 20024 U.S. Department of Justice (202) 205-8347 810 7th Street, NW [email protected] Washington, DC 20531 (202) 616-3649 Brecht Donoghue [email protected] Policy Advisor Office of the Assistant Attorney General Valerie Maholmes, Ph.D., CAS U.S. Department of Justice Director 810 7th Street, NW Social and Affective Development/Child Washington, DC 20531 Maltreatment & Violence Program (202) 305-1270 Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute [email protected] of Child Health and Human Development 6100 Executive Blvd. Shania Kapoor Room 4B05A Children Exposed to Violence (CEV) Fellow Bethesda, MD 20892 Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency (301) 496-1514 Prevention [email protected] U.S. Department of Justice 810 7th St., NW Karol Mason Washington DC 20531 Deputy Associate Attorney General (202) 514-5231 Office of the Associate Attorney General [email protected] U.S. Department of Justice 810 7th Street, NW Marylouise Kelley, Ph.D. Washington, DC 20531 Director [email protected] Family Violence Prevention and Services Program Family and Youth Services Bureau Amanda Nugent Administration on Children, Youth and Families Intern U.S. -

Thrift, Sacrifice, and the World War II Bond Campaigns

Saving for Democracy University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online Thrift and Thriving in America: Capitalism and Moral Order from the Puritans to the Present Joshua Yates and James Davison Hunter Print publication date: 2011 Print ISBN-13: 9780199769063 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769063.001.0001 Saving for Democracy Thrift, Sacrifice, and the World War II Bond Campaigns Kiku Adatto DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769063.003.0016 Abstract and Keywords This chapter recounts the war bond campaign of the Second World War, illustrating a notion of thrift fully embedded in a social attempt to serve the greater good. Saving money was equated directly with service to the nation and was pitched as a duty of sacrifice to support the war effort. One of the central characteristics of this campaign was that it enabled everyone down to newspaper boys to participate in a society-wide thrift movement. As such, the World War II war bond effort put thrift in the service of democracy, both in the sense that it directly supported the war being fought for democratic ideals and in the sense that it allowed the participation of all sectors in the American war effort. This national ethic of collective thrift for the greater good largely died in the prosperity that followed World War II, and it has not been restored even during subsequent wars in the latter part of the 20th century. Keywords: Second World War, war bonds, thrift, democracy, war effort Page 1 of 56 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com).