“I've Got to Succeed, So She Can Succeed, So We Can Succeed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey Head Once You Have Collected Each Coin!

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Contents: Disney’s Animal Kingdom Disney’s Hollywood Studios Epcot Magic Kingdom Downtown Disney WDW Resorts & Nearby Locations These Presses are currently out for refurbishment. Last Updated: April 29, 2010 Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Out of the Wild #1 Lion King 5 of 7, Rafiki Celebrate Culture South Africa Tarzan 7 of 8, Jane & Tarzan The Outpost Shop #1 Penny Presses Jungle Book 6 of 6, Share Khan Beastly Bazaar Safari Minnie Mouse Tarzan 4 of 8, Tantor Safari Pluto Lion King 3 of 7, Hula Timon Safari Goofy The Outpost Shop #2 Stink Bug Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #1 Tarzan 8 of 8, Jane Iguanodon Lion King 1 of 7, Simba Camtaurus Alioramus Rainforest Café #1 Hot Air Balloon, Orlando, FL Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #2 Mockingbird, Florida State Bird Tarzan 3 of 8, Terk Crab w/ Sunglasses, Orlando, FL Mickey with Fossil Alligator, Orlando, FL Lion King 6 of 7, Scar Restaurantosaurus #1 Dawa Bar Styracosaurus Lion Saltasaurus Hippopotamus Ankylosaurus Rhino Restaurantosaurus #2 Duka La Filimu #1 Tarzan 1 of 8, Tarzan & Jane Safari Mickey Duckosaurus Donald Safari Donald Dinosaur Skeleton Safari Goofy Wildlife Express Train Station #1 Duka La Filimu #2 Tarzan 2 of 8, Swinging Tarzan Safari Minnie Tarzan 5 of 8, Professor Safari Pooh Lion King 4 of 7, Pumba Safari Tigger Island Mercantile #1 Festival of The Lion -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

Masculinity in Children's Film

Masculinity in Children’s Film The Academy Award Winners Author: Natalie Kauklija Supervisor: Mariah Larsson Examiner: Tommy Gustafsson Spring 2018 Film Studies Bachelor Thesis Course Code 2FV30E Abstract This study analyzes the evolution of how the male gender is portrayed in five Academy Award winning animated films, starting in the year 2002 when the category was created. Because there have been seventeen award winning films in the animated film category, and there is a limitation regarding the scope for this paper, the winner from every fourth year have been analyzed; resulting in five films. These films are: Shrek (2001), Wallace and Gromit (2005), Up (2009), Frozen (2013) and Coco (2017). The films selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the Animated Feature film category tend to be both critically and financially successful, and watched by children, young adults, and adults worldwide. How male heroes are portrayed are generally believed to affect not only young boys who are forming their identities (especially ages 6-14), but also views on gender behavioral expectations in girls. Key words Children’s Film, Masculinity Portrayals, Hegemonic Masculinity, Masculinity, Film Analysis, Gender, Men, Boys, Animated Film, Kids Film, Kids Movies, Cinema, Movies, Films, Oscars, Ceremony, Film Award, Awards. Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 Problem Statements ____________________________________________________ 2 Method and Material ____________________________________________________ -

An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kramer, Heidi Tilney, "Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films by Heidi Tilney Kramer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Payne, Ph. D. Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 26, 2013 Keywords: children, animation, violence, nationalism, militarism Copyright © 2013, Heidi Tilney Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................ii Chapter One: Monsters Under -

White Savior, Savagery, & Criminality in Zootopia

White Savior, Savagery, & Criminality in Zootopia Nagata 1 A White Savior, Savagery, and Criminality in the City of “Multitudinous Opportunity” in Zootopia Matthew Nagata California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo White Savior, Savagery, & Criminality in Zootopia Nagata 2 Everyone comes to Zootopia thinking they can be anything they want, well you can’t. You can only be what you are. (Nick Wilde, 2016, Zootopia) The Disney company is distinguished for being the frontrunner in profit and popularity for animated movies worldwide. In 2016, Walt Disney Animation Studios released a film called Zootopia (Spencer, 2016). Not only did Zootopia win an Academy Award for best animated feature film, but the film also received a high score of 98% from the popular online movie review website RottenTomatoes, and made more than three hundred million dollars at the box- office (RottenTomatoes, 2016). The animated film is such a success that the Shanghai Disneyland theme park is getting its own Zootopia-land, which will be a replica of the city from the film that people will be able to walk-through and experience (Frater 2019). The Case of the Missing Animals Zootopia follows a small bunny named Judy Hopps who becomes the first bunny cop in Zootopia. Zootopia is a city in which animals of prey and those who are predators are able to put aside their hunting differences, and live together in harmony, until various predators start to go missing and become in touch with their more savage, “primal,” and violent instincts. Judy Hopps, along with a shady fox named Nick Wilde, take on the case of the missing animals. -

WHY NEMO MATTERS: ALTRUISM in AMERICAN ANIMATION by DAVID

WHY NEMO MATTERS: ALTRUISM IN AMERICAN ANIMATION by DAVID W. WESTFALL B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2007 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2009 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. L. Susan Williams Copyright DAVID W. WESTFALL 2009 Abstract This study builds on a small but growing field of scholarship, arguing that certain non- normative behavior is also non-negative, a concept referred to as positive deviance. This thesis examines positive behaviors, in the form of altruism, in the top 10 box-office animated movies of all time. Historically, studies focusing on negative, violent, and criminal behaviors garner much attention. Media violence is targeted as a cause for increasing violence, aggression, and antisocial behavior in youth; thousands of studies demonstrate that media violence especially influences children, a vulnerable group. Virtually no studies address the use of positive deviance in children’s movies. Using quantitative and ethnographic analysis, this paper yields three important findings. 1. Positive behaviors, in the form of altruism, are liberally displayed in children’s animated movies. 2. Altruism does not align perfectly with group loyalty. 3. Risk of life is used as a tool to portray altruism and is portrayed at critical, climactic, and memorable moments, specifically as movies draw to conclusion. Previous studies demonstrate that children are especially susceptible to both negativity and optimistic biases, underscoring the importance of messages portrayed in children’s movies. This study recommends that scholars and moviemakers consciously address the appearance and timing of positive deviance. -

Armed Forces

The Meat & Potatoes of Life Auto Matters and More! What’s Going On This Weekend Lisa Smith Molinari provides a look into Ludicrous acceleration and g-forces of the Senior games, arts & culture xperience, the life of her military family and offers her Incredicoaster will make you scream. pride art & music fest, brewfest, Rosh wisdom and wit. See page 8 See page 14 Hashanah, dog surfing. See page 18 Navy Marine Corps Coast Guard Army Air Force ARMED FORCES DISPATCHSan Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch www.armedforcesdispatch.com 619.280.2985 FIFTY EIGHTH YEAR NO. 14 Serving active duty and retired military personnel, veterans and civil service employees THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2018 September Monthly Obervances Nat’l Coupon Nat’l DNA, Geonomics & Stem Cell Education Nat’l Food Safety Education Nat’l Fruit and Veggies Nat’l Head Lice Prevention Nat’l Home Furnishings Nat’l Honey Nat’l Infant Mortality Aware- ness File photo of recovery efforts in Key West Fla. follow- Nat’l Mushroom ing Hurricane Irma in Sept. 2017. Navy photo Nat’l Organic Harvest Nat’l Osteopathic Medicine CNIC’s Ready Navy Program: Nat’l Ovarian Cancer Awareness ‘Get Ready, Get Set, Prepare!’ Nat’l Passport Awareness ASHINGTON - September is National Emergency Prepared- Nat’l Pet Memorial Wness Month. Commander, Navy Installations Command’s Nat’l Preparedness (CNIC) Ready Navy Program educates Sailors and their families on Nat’l Prostate Cancer how to be prepared when an emergency occurs. This year’s overall Awareness theme is “Disasters Happen. Prepare Now. Learn How.” Nat’l Prime Beef Each week in September will have a focused theme: Make and Nat’l Prosper Where You Are Practice Your Plan; Learn Life Saving Skills; Check Your Insurance Planted Coverage; and Save For an Emergency. -

“The Incredibles” Movie Scene Guide Howstuffworks.Com 1 “The

“The Incredibles” Movie Scene Guide “The Incredibles” Movie Scene Guide One thing that makes “The Incredibles” DVD so enjoyable is the ability for fans to repeatedly watch their favorite scenes. Here is a comprehensive guide to the scenes of “The Incredibles” Scene 1: Golden Age. Title sequence including vintage documentary interviews of Mr. Incredible, Elastigirl and Frozone. Scene 2: Weddings & Lawsuits. On his way to his wedding, Bob Parr turns into Mr. Incredible and takes several detours to heroically make rescues and foil crimes. His number one fan, Buddy, appears and asks to assist him as his sidekick Incrediboy, but Mr. Incredible dismisses him as he hurries away to foil another crime with flirty Elastigirl’s help. Buddy, however, gets in the way, causing a blast that requires Mr. Incredible to miraculously stop a train from crashing. Mission accomplished, he makes it to the church in time to say “I do” to Elastigirl at their wedding, but then learns that the rescued passengers are suing the city for damages, forcing the superheroes out of business and into seclusion. Scene 3: 15 Years & 50 Pounds Later. Forced to live secretly and anonymously as average suburbanites, Bob has a boring job in an insurance claims department, while Helen (formerly Elastigirl) is a housewife taking care of their baby Jack Jack while their son Dash and daughter Violet are at school. Scene 4: After School. Helen is called to the principal’s office after Dash is suspected of pulling a prank on his teacher. Violet hides coyly from her high school crush. Dad arrives home in his tiny car after a frustrating day at work. -

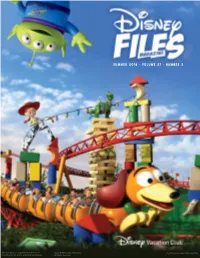

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2 Slinky® Dog is a registered trademark of Jenga® Pokonobe Associates. Toy Story characters ©Disney/Pixar Poof-Slinky, Inc. and is used with permission. All rights reserved. WeLcOmE HoMe Leaving a Disney Store stock room with a Buzz Lightyear doll in 1995 was like jumping into a shark tank with a wounded seal.* The underestimated success of a computer-animated film from an upstart studio had turned plastic space rangers into the hottest commodities since kids were born in a cabbage patch, and Disney Store Cast Members found themselves on the front line of a conflict between scarce supply and overwhelming demand. One moment, you think you’re about to make a kid’s Christmas dream come true. The next, gift givers become credit card-wielding wildebeest…and you’re the cliffhanging Mufasa. I was one of those battle-scarred, cardigan-clad Cast Members that holiday season, doing my time at a suburban-Atlanta mall where I developed a nervous tick that still flares up when I smell a food court, see an astronaut or hear the voice of Tim Allen. While the supply of Buzz Lightyear toys has changed considerably over these past 20-plus years, the demand for all things Toy Story remains as strong as a procrastinator’s grip on Christmas Eve. Today, with Toy Story now a trilogy and a fourth film in production, Andy’s toys continue to find new homes at Disney Parks around the world, including new Toy Story-themed lands at Disney’s Hollywood Studios (pages 3-4) and Shanghai Disneyland (page 22). -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

Pixar and Digital Culture Eric Duwayne Herhuth University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2015 Animating Aesthetics: Pixar and Digital Culture Eric DuWayne Herhuth University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Herhuth, Eric DuWayne, "Animating Aesthetics: Pixar and Digital Culture" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1000. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1000 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANIMATING AESTHETICS: PIXAR AND DIGITAL CULTURE by Eric Herhuth A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee August 2015 ABSTRACT ANIMATING AESTHETICS: PIXAR AND DIGITAL CULTURE by Eric Herhuth The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Patrice Petro In the pre-digital age of cinema, animated and live-action film shared a technological basis in photography and they continue to share a basis in digital technology. This fact limits the capacity for technological inquiries to explain the persistent distinction between animated and live-action film, especially when many scholars in film and media studies agree that all moving image media are instances of animation. Understanding the distinction in aesthetic terms, however, illuminates how animation reflexively addresses aesthetic experience and its function within contexts of technological, environmental, and socio-cultural change. “Animating Aesthetics: Pixar and Digital Culture” argues that the aesthetics that perpetuate the idea of animation as a distinct mode in a digital media environment are particularly evident in the films produced by Pixar Animation Studios. -

Elastigirl, and They Syndrome Is Killed in the Process

Teacher’s Notes Pearson EnglishTeacher’s Kids Readers Notes Pearson English Kids Readers Level 4 Suitable for: young learners who have completed up to 200 hours of study in English Type of English: American Headwords: 800 Key words: 15 (see pages 2 and 5 of these Teacher’s Notes) Key grammar: past simple including common irregular verbs, could for past ability and possibility, going to for prediction and intention, superlative adjectives, relative pronouns Summary of the story The Incredibles work together to defeat Syndrome and save the city. And finally, when Syndrome Mr. Incredible is the world’s best superhero. He tries to kidnap Jack-Jack, they save their baby and marries another superhero, Elastigirl, and they Syndrome is killed in the process. have a very exciting life. One day this all changes – no one wants the Background information superheroes anymore. Mr. Incredible (Bob Parr) and The Incredibles is a Disney-Pixar animated movie. Elastigirl (Helen Parr) become normal people and It was released in 2004 and was Pixar’s sixth full- have three children: Violet, Dash, and Jack-Jack. length movie production. Bob finds a normal job. It is boring and one day The movie was written and directed by Brad Bird. he pushes the boss and loses his job. The same It was inspired by the spy movies, comic books, evening, however, he receives an invitation from and TV shows of Brad Bird’s childhood. The movie a woman named Mirage to find and destroy a also explored personal frustrations about family, dangerous robot – the Omnidroid – on the island work, and our expectations of life.