The Subprime Mortgage Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carl Orffs Hesperische Musik

MATTHIAS JOHANNES PERNERSTORFER / WIEN Carl Orffs hesperische Musik Carl Orffs ‚Antigonae‘ (1940–49) und ‚Oedi pus der Tyrann‘ (1951– 58) nach Sophokles in der Übersetzung von Friedrich Hölderlin sowie der aischyleische ‚Prometheus‘ (1963–67) in der Originalsprache gehören zu den bedeutendsten Beiträgen zur musikalischen Rezeption der Antike im 20. Jahrhundert. Ich folge Stefan Kunze im Gebrauch der Bezeichnung Tragödien-Bearbeitungen für die genannten Bühnenwerke, da „kein musi- kalisches Werk (Vertonung) auf der Grundlage eines Tragödientextes … das Ziel [ist] …, sondern die [interpretative, Anm. d. A.1 ] Darstellung der Tragödie mit musikalischen Mitteln“.2 Es handelt sich um eine Form des Musiktheaters ganz eigener Art – „gleich weit entfernt vom Sprechtheater herkömmlicher Prägung wie von der Oper und von der … Bühnenmusik“.3 Auch wenn der Musikhistoriker Werner Schubert vor einigen Jahren dia- gnostizierte: „Daß es [Orff] … nicht um eine Rekonstruktion antiker Aufführungspraxis ging, muß man heute nicht mehr eigens betonen“,4 so möchte ich anmerken, daß die Tragödien-Bearbeitungen Orffs von vielen Philologen wie Theaterwissenschaftlern, die die musikwissenschaftliche Diskussion nicht mitverfolgen, wohl noch immer – sei es zustimmend oder ablehnend – als Rekonstruktionsversuche rezipiert werden. Der Grund dafür liegt in der zum Teil euphorischen Reaktion von zeitgenössischen Philologen, durch die Orffs Werke den Stellenwert von authentischen Wie- dergaben der altgriechischen Tragödien erreichten. Jahrzehntelang widmete sich Carl Orff den Tragödien-Bearbeitungen, wobei nicht von einem Weg des Komponisten in die Geistes- oder Musik- welt der Antike gesprochen werden kann. DieAntike diente ihm in Form —————————— 1 Zum Interpretationscharakter dieser „Darstellung der Tragödie“ s.u. 2 Kunze 1998, 547. 3 Schubert 1998, 405. 4 Schubert 1998, 403. 122 Matthias Johannes Pernerstorfer ihrer Texte als Medium, das er im Sinne von Höl derlins Antikerezeption mit Blick auf eine abendländische Gegenwart – deshalb ‚hesperisch‘ – gestaltete. -

Surviving Antigone: Anouilh, Adaptation, and the Archive

SURVIVING ANTIGONE: ANOUILH, ADAPTATION AND THE ARCHIVE Katelyn J. Buis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Jonathan Chambers ii ABSTRACT Dr. Cynthia Baron, Advisor The myth of Antigone has been established as a preeminent one in political and philosophical debate. One incarnation of the myth is of particular interest here. Jean Anouilh’s Antigone opened in Paris, 1944. A political and then philosophical debate immediately arose in response to the show. Anouilh’s Antigone remains a well-known play, yet few people know about its controversial history or the significance of its translation into English immediately after the war. It is this history and adaptation of Anouilh’s contested Antigone that defines my inquiry. I intend to reopen interpretive discourse about this play by exploring its origins, its journey, and the archival limitations and motivations controlling its legacy and reception to this day. By creating a space in which multiple readings of this play can exist, I consider adaptation studies and archival theory and practice in the form of theatre history, with a view to dismantle some of the misconceptions this play has experienced for over sixty years. This is an investigation into the survival of Anouilh’s Antigone since its premiere in 1944. I begin with a brief overview of the original performance of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone and the significant political controversy it caused. The second chapter centers on the changing reception of Anouilh’s Antigone beginning with the liberation of Paris to its premiere on the Broadway stage the following year. -

Llt 121 Classical Mythology Lecture 32 Good Morning

LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY LECTURE 32 GOOD MORNING AND WELCOME TO LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY IN WHICH WE RESUME OUR ADVENTURES IN THE CITY OF THEBES. THE CITY THAT THE GODS SEEM TO LOVE TO HATE. THE ORIGINAL FOUNDER TURNS INTO A SNAKE. WE'VE GOT THAT AT THEBES. A YOUNG MAN IS TURNED INTO A STAG FOR SEEING ARTEMIS BATHING IN THE NUDE. YES, WE HAVE THAT AT THEBES. THE SON KILLS THE FATHER. WE HAVE GOT THAT. WE DO THAT AT THEBES. THE SON MARRIES MOTHER. WE DO THAT TOO. BROTHER KILLS BROTHER, YEP. IF IT'S BAD AND IT HAPPENED IN ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY YOU CAN BET IT HAPPENED AT ANCIENT THEBES. I'VE ALREADY TOLD YOU WHY THAT IS. IT HAPPENS TO BE RIGHT NEXT DOOR TO ATHENS. WHERE I WANT TO START TODAY IS WITH ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS CHARACTERS IN ALL WESTERN CIVILIZATION, ONE OF THE MOST COMPLEX PEOPLE YOU'LL EVER WANT TO MEET. THIS GUY IS BY THE NAME OF OEDIPUS. OEDIPUS STARTS OFF AS A LITTLE BABY. HE IS A CUTE LITTLE BABY. HE USED TO BE A LITTLE BOY. THEN HE WINDS UP AS THIS SAD, MULING, PUKING, UNHAPPY MAN WHO HAS POKED HIS OWN EYES OUT WITH A BROOCH. THIS IS THE GORE DRIPPING OUT OF HIS EYES AND ALL OF THAT BECAUSE HE SUFFERS FROM CLASSICAL GREEK MYTHOLOGY'S WORST DOCUMENTED CASE OF ARTIMONTHONO. NOW I GET IT. I PAUSE FOR YOUR QUESTIONS UP TO THIS POINT. WHEN LAST WE LEFT OFF LAIUS HAD BECOME KING AFTER A LONG WAIT WITH SOME INTERESTING MATHEMATICS BEHIND IT IF YOU'LL RECALL. -

A Psychoanalytic Study of Sophocles' Antigone Authors: Almansi, Renato, J

EBSCOhost http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/delivery?sid=6f63c990-0c3e-4396-979b... Record: 1 Title: A Psychoanalytic Study of Sophocles' Antigone Authors: Almansi, Renato, J. Source: Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 1991; v. 60, p69, 17p ISSN: 00332828 Document Type: Article Language: English Abstract: This paper examines, in a detailed and comprehensive fashion, the unconscious motivations of the main protagonists of Sophocles' Antigone and the play's general structure as a psychoanalytically coherent whole. This examination helps to foster an understanding of the conceptual place of Antigone within the Oedipus Trilogy, its relationship to Oedipus Rex, and the complementary character of these two tragedies. Accession Number: PAQ.060.0069A Database: PEP Archive A Psychoanalytic Study of Sophocles' Antigone Renato J. Almansi, M.D.; 200 East 89th St., Apt. 41B New York, NY 10128 ABSTRACT This paper examines, in a detailed and comprehensive fashion, the unconscious motivations of the main protagonists of Sophocles' Antigone and the play's general structure as a psychoanalytically coherent whole. This examination helps to foster an understanding of the conceptual place of Antigone within the Oedipus Trilogy, its relationship to Oedipus Rex, and the complementary character of these two tragedies. Antigone was first produced in the year 442 B.C., the first of the three plays of the Oedipus Trilogy. Oedipus Rex was produced between 430 and 425 B.C., and Oedipus at Colonus posthumously in 401 B.C. As we shall see, this sequence may be psychologically significant. Since the very beginning, Antigone has been the object of great interest: it immediately made Sophocles famous, and throughout the ages it has caused an outpouring of comments and hypotheses stimulated by the multiplicity of political, social, and philosophical issues the play seems to raise and by its enigmatic quality. -

Sophocles' Antigone Reworked in the Twentieth

NEW VOICES IN CLASSICAL RECEPTION STUDIES Issue 12 (2018) SOPHOCLES’ ANTIGONE REWORKED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE CASE OF HASENCLEVER’S ANTIGONE (1917) © Rossana Zetti (University of Edinburgh) INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXTUALIZATION This article examines a little-known example of Antigone’s reception in the twentieth century: the adaptation by the German expressionist writer Walter Hasenclever. This version is the first and arguably most innovative of several European adaptations of Sophocles’ play to appear in the first half of the twentieth century. Although successful at the time of its production, Hasenclever’s Antigone is scarcely read in contemporary scholarship and is discussed mainly in German-language scholarship.1 Whereas Flashar’s wide-ranging study, in German, refers to Hasenclever’s drama (Flashar 2009: 127– 29), in Fischer-Lichte’s 2017 book Tragedy’s Endurance, in English, Hasenclever appears only in one endnote (Fischer-Lichte 2017: 143). The only English translation of the play available (Ritchie and Stowell 1969: 113–60) is rather out of date and inaccessible. Hasenclever’s Antigone is briefly mentioned in Steiner’s essential reference book Antigones (Steiner 1984: 142; 146; 170; 218), in the chapter on Antigone in the recent Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Sophocles (Silva 2017: 406–7) and in Cairns’ 2016 book on Sophocles’ Antigone (Cairns 2016: 133). However, it is absent in some of the most recent contributions dedicated to the play’s modern reception, including Wilmer’s and Žukauskaitė’s edited collection on Antigone in postmodern thought (2010), Mee’s and Foley’s essays (2011) discussing adaptations of Antigone staged around the world, and Morais’, Hardwick’s and Silva’s recent volume (2017).2 The absence of Hasenclever from contemporary scholarship can be explained by the fact that his Antigone lacks the complexity of later adaptations, such as Anouilh’s and Brecht’s. -

Brecht's Antigone in Performance

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY RHYTHM AND STRUCTURE: BRECHT’S ANTIGONE IN PERFORMANCE BRUNO C. DUARTE FCSH UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA Brecht’s adaptation of Sophocles’ Antigone in 1948 was openly a political gesture that aspired to the complete rationalization of Greek Tragedy. From the beginning, Brecht made it his task to wrench ancient tragic poetry out of its ‘ideological haze’, and proceeded to dismantle and eliminate what he named the ‘element of fate’, the crucial substance of tragic myth itself. However, his encounter with Hölderlin's unorthodox translation of Antigone, the main source for his appropriation and rewriting of the play, led him to engage in a radical experiment in theatrical practice. From the isolated first performance of Antigone, a model was created—the Antigonemodell —that demanded a direct confrontation with the many obstacles brought about by the foreign structure of Greek tragedy as a whole. In turn, such difficulties brought to light the problem of rhythm in its relation to Brecht’s own ideas of how to perform ancient poetry in a modern setting, as exemplified by the originally alienating figure of the tragic chorus. More importantly, such obstacles put into question his ideas of performance in general, as well as the way they can still resonate in our own understanding of what performance is or might be in a broader sense. 1947–1948: Swabian inflections It is known that upon returning from his American exile, at the end of 1947, Bertolt Brecht began to work on Antigone, the tragic poem by Sophocles. Brecht’s own Antigone premiered in the Swiss city of Chur on February 1948. -

Kodály and Orff: a Comparison of Two Approaches in Early Music Education

ZKÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Cilt 8, Sayı 15, 2012 ZKU Journal of Social Sciences, Volume 8, Number 15, 2012 KODÁLY AND ORFF: A COMPARISON OF TWO APPROACHES IN EARLY MUSIC EDUCATION Yrd.Doç.Dr. Dilek GÖKTÜRK CARY Karabük Üniversitesi Safranbolu Fethi Toker Güzel Sanatlar ve Tasarım Fakültesi Müzik Bölümü [email protected] ABSTRACT The Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) and the German composer Carl Orff (1895-1982) are considered two of the most influential personalities in the arena of music education during the twentieth-century due to two distinct teaching methods that they developed under their own names. Kodály developed a hand-sign method (movable Do) for children to sing and sight-read while Orff’s goal was to help creativity of children through the use of percussive instruments. Although both composers focused on young children’s musical training the main difference between them is that Kodály focused on vocal/choral training with the use of hand signs while Orff’s main approach was mainly on movement, speech and making music through playing (particularly percussive) instruments. Finally, musical creativity via improvisation is the main goal in the Orff Method; yet, Kodály’s focal point was to dictate written music. Key Words: Zoltán Kodály, Carl Orff, The Kodály Method, The Orff Method. KODÁLY VE ORFF: ERKEN MÜZİK EĞİTİMİNDE KULLANILAN İKİ METODUN BİR KARŞILAŞTIRMASI ÖZET Macar besteci ve etnomüzikolog Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) ve Alman besteci Carl Orff (1895-1982) geliştirmiş oldukları farklı 2 öğretim metodundan dolayı 20. yüzyılda müzik eğitimi alanında en etkili 2 kişi olarak anılmaktadırlar. Kodály çocukların şarkı söyleyebilmeleri ve deşifre yapabilmeleri için el işaretleri metodu (gezici Do) geliştirmiş, Orff ise vurmalı çalgıların kullanımı ile çocukların yaratıcılıklarını geliştirmeyi hedef edinmiştir. -

Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft

Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft Eine Einführung in Schwierigkeiten, Herrschaft zu begreifen Herausgegeben von Uta v. Winterfeld V VS Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft Wolf-Dieter Narr, Politikwissenschaftler, war von 1971 bis 2002 Professor am Otto-Suhr-Institut der Freien Universität Berlin, Mitgründer und Mitsprecher des Komitees für Grundrechte und Demokratie. Uta von Winterfeld, Politikwissenschaftlerin, ist Projektleiterin am Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie und Privatdozentin am Otto-Suhr-Institut der Freien Universität Berlin. Wolf-Dieter Narr Niemands-Herrschaft Eine Einführung in Schwierigkeiten, Herrschaft zu begreifen Herausgegeben von Uta v. Winterfeld VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de Die Drucklegung wird finanziell gefördert von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. © VSA: Verlag 2015, St. Georgs Kirchhof 6, 20099 Hamburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten Umschlaggestaltung unter Verwendung eines Bildes von Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751-1829) mit dem Motiv »Odysseus flieht mit seinen Gefährten im Schiff vor Polyphem« Druck- und Buchbindearbeiten: CPI Books GmbH, Leck ISBN 978-3-89965-600-8 Inhalt Prolog ........................................................................................................................ 9 Kapitel I Jeder und Jedem ihre oder seine »Theorie« ? ................................................. 13 Theorie und Wirklichkeit ...................................................................................... 13 Theorie und Praxis ................................................................................................ -

Thebaid 2: Oedipus Descendants of Cadmus

Thebaid 2: Oedipus Descendants of Cadmus Cadmus = Harmonia Aristaeus = Autonoe Ino Semele Agave = Echion Pentheus Actaeon Polydorus (?) Autonoe = Aristaeus Actaeon Polydorus (?) • Aristaeus • Son of Apollo and Cyrene • Actaeon • While hunting he saw Artemis bathing • Artemis set his own hounds on him • Polydorus • Either brother or son of Autonoe • King of Cadmeia after Pentheus • Jean-Baptiste-Camile Corot ca. 1850 Giuseppe Cesari, ca. 1600 House of Cadmus Hyrieus Cadmus = Harmonia Dirce = Lycus Nycteus Autonoe = Aristaeus Zeus = Antiope Nycteis = Polydorus Zethus Amphion Labdacus Laius Tragedy of Antiope • Polydorus: • king of Thebes after Pentheus • m. Nycteis, sister of Antiope • Polydorus died before Labdacus was of age. • Labdacus • Child king after Polydorus • Regency of Nycteus, Lycus Thebes • Laius • Child king as well… second regency of Lycus • Zethus and Amphion • Sons of Antiope by Zeus • Jealousy of Dirce • Antiope imprisoned • Zethus and Amphion raised by shepherds Zethus and Amphion • Returned to Thebes: • Killed Lycus • Tied Dirce to a wild bull • Fortified the city • Renamed it Thebes • Zethus and his family died of illness Death of Dirce • The Farnese Bull • 2nd cent. BC • Asinius Pollio, owner • 1546: • Baths of Caracalla • Cardinal Farnese • Pope Paul III Farnese Bull Amphion • Taught the lyre by Hermes • First to establish an altar to Hermes • Married Niobe, daughter of Tantalus • They had six sons and six daughters • Boasted she was better than Leto • Apollo and Artemis slew every child • Amphion died of a broken heart Niobe Jacques Louis David, 1775 Cadmus = Harmonia Aristeus =Autonoe Ino Semele Agave = Echion Nycteis = Polydorus Pentheus Labdacus Menoecius Laius = Iocaste Creon Oedipus Laius • Laius and Iocaste • Childless, asked Delphi for advice: • “Lord of Thebes famous for horses, do not sow a furrow of children against the will of the gods; for if you beget a son, that child will kill you, [20] and all your house shall wade through blood.” (Euripides Phoenissae) • Accidentally, they had a son anyway. -

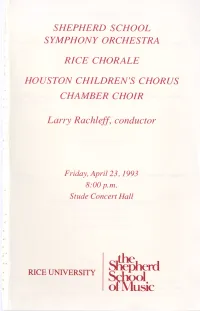

Of Music PROGRAM

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICE CHORALE HOUSTON CHILDREN'S CHORUS CHAMBER CHOIR Larry Rachleff, conductor Friday, April23, 1993 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall "-' sfkteherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol Of Music PROGRAM Fanfare for a Great City Arthur Gottschalk (b. 1952) Variations on a Theme of Joseph Haydn, Op. 56a Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) INTERMISSION Carmina Burana Carl Orff ( 1895-1982) Rice Chorale Houston Children's Chorus Chamber Choir Kelley Cooksey, soprano Francisco Almanza, tenor Robert Ames, baritone In consideration of the performers and members of the audience, please check audible paging devices with the ushers and silence audible timepieces. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are prohibited. SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Violin I Viola (cont.) Oboe Trumpet (cont.) Julie Savignon, Erwin Foubert Margaret Butler Troy Rowley concertmaster Patrick Horn Kyle Bruckmann David Workman Claudia Harrison Stephanie Griffin Jeffrey Champion Trombone Barbara Wittenberg Bin Sun Dione Chandler Wade Demmert Jeanine Tiemeyer Andrew Weaver Karen Friedman David Ford Kristin Lacey Sharon Neufeld ~ Brent Phillips Mihaela Oancea English Horn Cello Kyle Bruckmann Inga Ingver Tuba Katherine de Bethune, Yenn Chwen Er Clarinet Jeffrey Tomberg principal Yoong-han Chan Benjamin Brady Danny Urban ~ Jeanne Jaubert Magdalena Villegas Joanne Court Scott Brady Timpani and Tanya Schreiber Kelly Cramm Mary Ellen Morris Percussion Rebecca Ansel Martin van Maanen Robin Creighton Douglas Cardwell Eitan Ornoy X in-Yang Zhou Amy -

Sophocle's ANTIGONE Adapted by Lewis Galantiere from the Play By

Sophocle’s ANTIGONE Adapted by Lewis Galantiere From the play by Jean Anouilh Re-imagined for 5 Actors by Christopher Scott Dramatis Personae: Chorus/ Nurse Antigone Ismene/ Messenger Haemon/ The Guard Creon The Royal Palace in Thebes Chorus Well, here we are. These people that you see here are about to act out for you the story of Antigone. (He looks at Antigone,) That dark-haired girl sitting by herself, staring straight ahead, seeing nothing, is Antigone. She is thinking. She is thinking that the instant I finish telling you who's who and what's what in this play, she will burst forth as the dark, tense, serious girl, who is about to rise up and face the whole world alone—alone against the world and against Creon, her uncle, the King. Another thing that she is thinking is this: she is going to die. Antigone is young. She would much rather live than die. But there is no help for it. When you are on the side of the gods against the tyrant, of Man against the State, of purity against corruption—when, in short, your name is Antigone, there is only one part you can play; (Chorus turns and looks at her) and she will have to play hers through to the end. Mind you, Antigone doesn't know all these things about herself. I know them because it is my business to know them. That's what a Greek Chorus is for. All that she knows is that Creon won't allow her dead brother to be buried; and that despite Creon, she must bury him. -

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release 056030 V/A Soulshine's Soulful...2 1 Cd € 20 Nld Cstar 2st 8/01/2003 029148 Adler, Larry Great Larry Adler 1 Cd € 19 Eu Flapp A/R 26/02/1996 076013 Aurelie Desde Que Naci 1 Cd € 16 Eu Swim A/R 21/12/2004 076478 Catching Flies Just a Phase 1 Cd € 19 Eu Arts A/R 31/12/1999 070884 City City City Dawn and the Blue Light D 1 Cd € 25 Imp Senpr A/R 29/03/2004 010387 For.Mat Media Circus 1 Cd € 18 Usa Setan A/R 30/06/1990 045097 Half Hour To Go Items For the Full Outfit 1 Cd € 21 Usa Grass A/R 18/06/1996 028140 Hurlements D'leo Ouest Terne 1 Cd € 25 Nld Wagra A/R 12/09/2008 053085 La Crus Dentro Me 1 Cd € 21 Eu Warne A/R 10/02/2000 064901 La Crus Dentro Me 1 Cd € 22 Eu Wealo A/R 10/02/2000 064921 La Crus Dietro La Curva Del Cuore 1 Cd € 22 Eu Warne A/R 9/02/1999 056224 Lawn Backspace 1 Cd € 20 Nld My Fi A/R 23/10/2003 036508 Maple It's My Last Night 1 Cd € 20 Usa Slab A/R 26/02/1996 015227 Modest Mouse This is a Long Drive 1 Cd € 20 Usa Up Re A/R 26/03/1996 040539 More Dogs Never Let Them Catch 1 Cd € 20 Usa Monit A/R 3/05/2005 051289 Nein Wrath of Circuits 1 Cd € 19 Usa So.Un A/R 17/05/2005 075942 Pee Now More Charm and More.