In Iranian-Indian Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Manusya Manvantara(M)

MANUSYA 482 MANVANTARA(M) MANUSYA (MAN) The Puranas. have not given a 42,200 divine days (120 x 360) which is the life-span of definite explanation regarding the origin of Man, the a Brahma, a deluge takes place. Thus in one Brahma's most important of all living beings. Many stories time 42,200 Kalpas take place. A Brahma's life span regarding the origin of Man were current among the is known as "Mahakalpa" and the close of a Brahma's ancient people. According to Hindu Puranas Man period is called "Mahapralaya". was born of Svayambhuva Manu who in turn was born 2) Human year (Manufya varfd) and Divine year (Deva of Brahma. According to Valmiki Ramayana (Sarga 14, varsa) . When two leaves are placed one over the other Aranya Kanda) all the living beings including man and they are pierced by a needle, the time required were born to Kasyapaprajapati of his eight wives, for the needle to pass from the first leaf to the second Aditi, Dili, Danu, Kalika, Tamra, Krodhavasa, Manu is called "Alpakala". Thirty such alpakalas make one and Anala. From Aditi were born the devas; from "Truti". Thirty trutis make one "Kala". Thirty Kalas Dili, the daityas; from Danu, the danavas; from Kali, make one "Kastha", which is also known as "Nimisa" the asuras Kalaka and Naraka; from Tamra, the bird- "Noti" or "Matra". Four "Nimisas" make one flock Kraunci, Bhasi, Syenl, Dhrtarastri and Suki; "Ganita". Ten Ganitas, one "Netuvlrppu". Six netu- from KrodhavaSa the animal flock, Mrgl, Mrgamanda, virppus, one "Vinazhika". Sixty vinazhikas one ' Hari, Bhadramada, MfitangI, Sardull, Sveta and Ghatika". -

Balabodha Sangraham

बालबोध सङ्ग्रहः - १ BALABODHA SANGRAHA - 1 A Non-detailed Text book for Vedic Students Compiled with blessings and under instructions and guidance of Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 69th Peethadhipathi and Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sri Sri Sankara Vijayendra Saraswathi Sri Sankaracharya Swamiji 70th Peethadhipathi of Moolamnaya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Offered with devotion and humility by Sri Atma Bodha Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Kumbakonam Swamiji) Disciple of Pujyasri Kuvalayananda Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Tambudu Swamiji) Translation from Tamil by P.R.Kannan, Navi Mumbai Page 1 of 86 Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham ॥ श्रीमहागणपतये नमः ॥ ॥ श्री गु셁भ्यो नमः ॥ INTRODUCTION जगत्कामकलाकारं नािभस्थानं भुवः परम् । पदपस्य कामाक्षयाः महापीठमुपास्महे ॥ सदाििवसमारमभां िंकराचाययमध्यमाम् । ऄस्मदाचाययपययनतां वनदे गु셁परमपराम् ॥ We worship the Mahapitha of Devi Kamakshi‟s lotus feet, the originator of „Kamakala‟ in the world, the supreme navel-spot of the earth. We worship the Guru tradition, starting from Sadasiva, having Sankaracharya in the middle and coming down upto our present Acharya. This book is being published for use of students who join Veda Pathasala for the first year of Vedic studies and specially for those students who are between 7 and 12 years of age. This book is similar to the Non-detailed text books taught in school curriculum. We wish that Veda teachers should teach this book to their Veda students on Anadhyayana days (days on which Vedic teaching is prohibited) or according to their convenience and motivate the students. -

Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Franke, Thomas. "Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375)." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/30 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Samuel Franke Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Michael A. Ryan , Chairperson Timothy C. Graham Sarah Davis-Secord Franke i MONSTERS AT THE END OF TIME: GOG AND MAGOG AND ETHNIC DIFFERENCE IN THE CATALAN ATLAS (1375) by THOMAS FRANKE BACHELOR OF ARTS, UC IRVINE 2012 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico JULY 2014 Franke ii Abstract Franke, Thomas. Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375). University of New Mexico, 2014. Although they are only mentioned briefly in Revelation, the destructive Gog and Magog formed an important component of apocalyptic thought for medieval European Christians, who associated Gog and Magog with a number of non-Christian peoples. -

Kaala Vichara

|| shrI: || kAlAntargata kAla niyAmaka kAlAtIta trikAlagnya | kAlapravartaka kAlanivartaka kAlOtpAdaka kAlamUrti || KAALA VICHARA Prepared based on the lectures of Shri Bannanje Govindacharyaru and Shri HarikathAmRutasAra grantha (Sandhi: AparOkSha tAratamya or Kalpa Sadhana) Parama sUkShma kAlAmsha is considered to be 'kshaNa'. kshaNa could further be divided into smaller portions, but since it becomes difficult for human beings to contemplate, the smallest particle is considered as kShaNa. Kaala Vichara of Manavas: S.No. Smaller Time Unit Bigger Time Unit 1. KShaNa - 2. 5 KShaNas TRuTi 3. 50 TRuTis 1 Lava 4. 2 Lava 1 NimEsha 5. 8 NimEshas 1 Matra 6. 2 Matras 1 Guru 7. 10 Gurus 1 PraNa 8. 6 PraNas 1 PaLa 9. 60 PaLas 1 GhaTika 10. 30 GhaTikas 12 hrs 11. 60 GhaTikas 24 hrs (1 Day + 1 Night) 12. 15 Days 1 PakSha 13. 2 PakShas 1 Maasa (month) 14. 2 Masas 1 Rutu 15. 3 Rutus 1 Ayana 16. 2 Ayanas 1 Varsha (Year) 17. 360 Man Days 1 Man Year ShrImad HarikathAmrutasAra quotations from aparOksha tAratamya/kalpa sAdhana sandhi: paramasUkshma kshaNavaidu tRuTi | karesuvudu aivattu tRuTi lava | eradu lavavu nimEsha nimEshagaLentu mAtra yuga | guru dasha prANavu paLavu ha | nneradu bANavu ghaLige trimshati | iruLu hagalaravattu ghatikagaLahOrAtrigaLu || 56 || I divArAtrigaLeraDu hadi | naidu pakShagaLeraDu mAsaga | LAdapavu mAsadvayave Rutu RututrayagaLayana | aiduvuvu ayanadvayAbda kRu | tAdiyugagaLu dEvamAnadi | dwAdasha sahasra varuShagaLahavadanu pELuvenu || 57 || Kaala Vichaara of Devata-s (Upper Planetary Plane): 360 Man Days or 1 Man Year = 1 DEvata Day => 360 Man years = 1 DEvata year => 129,600 Man Days = 1 dEvatha year Kaala Vichara of Chaturyuga (kRuta - trEta - dwApara – kali) DY -> dEvata Year MY -> Man/Manava Year S.No. -

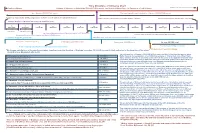

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

Life Science Journal 2012;9(1S) Http

Life Science Journal 2012;9(1s) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Iranian Zurvanism, Origin of Worshipping Evil ELIKA BAGHAIE PHD candidate at the Tajikistan Academy of science Abstract: In this article it is attempted to study the philosophy of the emergence of evil forces in the history of human life from the perspective of the East ancient texts, particularly those of ancient Iran and middle Persian language and then Zurvan, its emergence and status beyond a creator and as a neutral element and an evil force, and its logical concept is studied. “Above is not bright. Below is not dark. It’s invisible, and it can’t be called by any name. [ELIKA BAGHAIE. Iranian Zurvanism, Origin of Worshipping Evil. Life Sci J 2012;9(1s):21-26] (ISSN:1097-8135). http://www.lifesciencesite.com. 5 Keywords: creation, evil, duality, Zurvan, man, God 1. Introduction Etymology of Zruuan, which is generally In a narration by Plutarch it is stated that defined as “time” in Avestan language is indefinite in Theopompus has remarked in the first half of 4th available documents and references. On the other century B.C. that “A group of people believe in two hand , it could be said that this term is linked to gods who are like to masons, one of them is creator Avestan zauruuan- which means “ancient time , old of good and the other one is creator of evil and age” ,and zaurura- which means “ancient and worn- useless things. And a group of people call the good out” which are derived from primitive Indo-European force as God and the other one as the Evil. -

{Download PDF} Visions of a Future the Study of Christian Eschatology

VISIONS OF A FUTURE THE STUDY OF CHRISTIAN ESCHATOLOGY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Zachary Hayes | 9780814657423 | | | | | Visions of a Future The Study of Christian Eschatology 1st edition PDF Book These lines also bring into vivid focus how thoroughly and profoundly eschatological is the faith that calls Jesus of Nazareth the Christ. Their interpretation of Christian eschatology resulted in the founding of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Though it has been used differently in the past, the term is now often used by certain believers to distinguish this particular event from the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to Earth mentioned in Second Thessalonians , Gospel of Matthew , First Corinthians , and Revelation , usually viewing it as preceding the Second Coming and followed by a thousand-year millennial kingdom. Indeed, critics of dispensationalism often charge that the dispensationalist eschatology inclines its adherents not only to despair of changing the world for good, but even to take a certain grim satisfaction in the face of wars and natural disasters, events which they interpret as the fulfillment of prophecy pointing to the end of the world. Nashville: Abingdon. However, the eschatological character of the century cannot be captured by focusing only on academic theology and high-level ecclesial declarations. Wandering in darkness: narrative and the problem of suffering. This is a reference to the Caesars of Rome. The number identifying the future empire of the Anti-Christ, persecuting Christians. In this sense, his whole life was eschatological. Caragounis, C. Given the nature of such literature, it is hardly surprising that it holds such fascination. Dislocating the Eschaton? The urge to correlate these with contemporary events and world leaders is one that interpreters in many ages have found hard to resist. -

Nicholas M. Railton Gog and Magog: the History of a Symbol

EQ 75:1 (2003),23-43 Nicholas M. Railton Gog and Magog: the History of a Symbol Dr Nicholas Railton is lecturer in German at the University of Ulster. He has published books on the history of the Evangelical Alliance (The German Evangelical Alliance and the Third Reich, 1998; No North Sea. The Anglo-German Evangelical Network in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century, 2000) and articles on Christian responses to the Third Reich. Key words: Bible; Gog; Magog; symbolism. World politics, like the history of Gog and Magog, are very confused and much disputed. (Winston Churchill, 9 November 1951). Introduction Gog from the land of Magog, one of the great enemies of the people of God to appear at the end of the historical process, has vexed and bewildered exegetes for centuries. The prophet Ezekiel seems to speak of an unrepentant nation and its head and communicates God's impending judgement (Ezekiel 38:1-3, New American Stan- dard Bible) : .. And the word of the Lord came to me saying, 'Son of man, set your face toward Gog of the land of Magog, the prince of Rosh, Meshech and Tubal and prophesy against him and say, "Thus says the Lord God, 'Behold, I am against you, 0 Gog, prince of Rosh, Meshech and Tubal.'"' An examination of the historical development of this eschatologi cal idea, this Feindbild, will introduce us to the never-ending attempts to decipher these millennial foes inhabiting the areas to the far north of Palestine. This brief survey shows how the desire to interpret the signs of the times and understand the period in which one is living can, and usually has entrenched religious believers in an inflexible, nationalistic and self-righteous mind-set. -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise. -

An Examination of the Possibility of Persian Influence on the Tibetan Bon Religion

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 From a Land in the West: An Examination of the Possibility of Persian Influence on the Tibetan Bon Religion Jeremy Ronald McMahan College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation McMahan, Jeremy Ronald, "From a Land in the West: An Examination of the Possibility of Persian Influence on the Tibetan Bon Religion" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 715. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/715 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From a Land in the West: An Examination of the Possibility of Persian Influence on the Tibetan Bon Religion A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Religious Studies from The College of William and Mary by Jeremy Ronald McMahan Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Kevin Vose, Director ________________________________________ Chrystie Swiney ________________________________________ Melissa Kerin Williamsburg, VA April 27, 2010 1 Introduction Since coming to light during the 19th and 20th centuries, Bon, Tibet's “other” religion, has consistently posed a problem for Western scholarship. Claiming to be the original religion of Tibet, to the untrained eye Bon looks exactly like Tibetan Buddhism. -

Zoroastrianism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search Zoroastrianism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss Main page these issues on the talk page. Contents The neutrality of this article is disputed. (March 2012) Featured content This article may contain previously unpublished synthesis of Current events published material that conveys ideas not attributable to the Random article original sources. (March 2012) Donate to Wikipedia This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often Interaction accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (March 2012) Help Part of a series on About Wikipedia Zoroastrianism /ˌzɒroʊˈæstriənɪzəm/, also called Mazdaism Zoroastrianism Community portal and Magianism, is an ancient Iranian religion and a religious Recent changes philosophy. It was once the state religion of the Achaemenid, Contact page Parthian, and Sasanian empires. Estimates of the current number of Zoroastrians worldwide vary between 145,000 and Toolbox 2.6 million.[1] Print/export In the eastern part of ancient Persia more than a thousand The Faravahar, believed to be a depiction of a fravashi years BCE, a religious philosopher called Zoroaster simplified Languages Primary topics the pantheon of early Iranian gods[2] into two opposing forces: Afrikaans Ahura Mazda Ahura Mazda (Illuminating Wisdom) and Angra Mainyu Alemannisch Zarathustra (Destructive Spirit) which were in conflict. aša (asha) / arta Angels and demons ا open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Angels and demons ا Aragonés Zoroaster's ideas led to a formal religion bearing his name by Amesha Spentas · Yazatas about the 6th century BCE and have influenced other later Asturianu Ahuras · Daevas Azərbaycanca religions including Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity and Angra Mainyu [3] Беларуская Islam.