Genevath 40 World Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

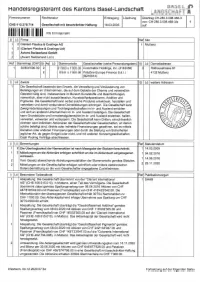

Handelsregisteramt Des Kantons Basel-Landschaft Lllllililililiil Ilril Il

Handelsregisteramt des Kantons Basel-Landschaft BASEL lp LANDSCHAFT t Firmennummer Rechtsnatur Eintragung Löschung Ubertrag CH-280.3.008.468-3 von: CH-280.3.008.468-3/a 1 cHE-112.279.714 Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haft ung 18.03.2005 auf: lllllililililIil ilril il Alle Eintragungen Ei Lö Firma Rel Sitz 1 2 elarian*ebsties feoatings-AG 1 Muttenz 1 2 @ 2 Avient Switzerland GmbH 2 (Avient Switzerland LLC) Ref Stammkap.(CHF) Ei Ae Lö Stammanteile Gesellschafter (siehe Personalangaben) Ei Lö Domiziladresse 1 30'804'000.00 2 21'563 x 1'000.00 Colormatrix Holdings, lnc. (41 42456) 1 Rothausstrasse 61 2 9'241x 1'000.00 PolyOne Europe Finance S.ä.r.1. 4't 32 Muttenz (P'210614) Ei Lö Zweck Ei Lö weitere Adressen 1 Die Gesellschaft bezweckt den Erutrerb, die Verwaltung und Veräusserung von Beteiligungen an Unternehmen, die auf dem Gebiete der Chemie und venruandten Gebieten tätig sind, insbesondere im Bereich Kunststoffe und Beschichtungen, namentlich, aber nicht ausschliesslich, Kunststoffpräparationen, Additive und Pigmente. Die Gesellschaft kann selbst solche Produkte entwickeln, herstellen und vertreiben und damit verbundene Dienstleistungen erbringen. Die Gesellschaft kann Zweigniederlassungen und Tochtergesellschaften im ln- und Ausland errichten und sich an anderen Unternehmen im ln- und Ausland beteiligen. Die Gesellschaft kann Grundstücke und lmmaterialgüterrechte im ln- und Ausland eniverben, halten, verwalten, verwerten und veräussern. Die Gesellschaft kann Dritten, einschliesslich direkten oder indirekten Aktionären der Gesellschaft oder Gesellschaften, an denen solche betdiligt sind, direkte oder indirekte Finanzierungen gewähren, sei es mittels Darlehen oder anderen Finanzierungen oder durch die Stellung von Sicherheiten jeglicher Art, ob gegen Entgelt oder nicht, und mit anderen Konzerngesellschaften Cash Pooling Verträge abschliessen. -

Canton of Basel-Stadt

Canton of Basel-Stadt Welcome. VARIED CITY OF THE ARTS Basel’s innumerable historical buildings form a picturesque setting for its vibrant cultural scene, which is surprisingly rich for THRIVING BUSINESS LOCATION CENTRE OF EUROPE, TRINATIONAL such a small canton: around 40 museums, AND COSMOPOLITAN some of them world-renowned, such as the Basel is Switzerland’s most dynamic busi- Fondation Beyeler and the Kunstmuseum ness centre. The city built its success on There is a point in Basel, in the Swiss Rhine Basel, the Theater Basel, where opera, the global achievements of its pharmaceut- Ports, where the borders of Switzerland, drama and ballet are performed, as well as ical and chemical companies. Roche, No- France and Germany meet. Basel works 25 smaller theatres, a musical stage, and vartis, Syngenta, Lonza Group, Clariant and closely together with its neighbours Ger- countless galleries and cinemas. The city others have raised Basel’s profile around many and France in the fields of educa- ranks with the European elite in the field of the world. Thanks to the extensive logis- tion, culture, transport and the environment. fine arts, and hosts the world’s leading con- tics know-how that has been established Residents of Basel enjoy the superb recre- temporary art fair, Art Basel. In addition to over the centuries, a number of leading in- ational opportunities in French Alsace as its prominent classical orchestras and over ternational logistics service providers are well as in Germany’s Black Forest. And the 1000 concerts per year, numerous high- also based here. Basel is a successful ex- trinational EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse- profile events make Basel a veritable city hibition and congress city, profiting from an Freiburg is a key transport hub, linking the of the arts. -

Info-Plan 190822.Pdf

ZENTRUM Gemeinde 16a 6 9 Birsfelden 8a 7 35b 6a 1 Bürklinstrasse 7a 5 10 10a 5b 7 41a 4 5 8 49d 9a 5 5 Gemeindeverwaltung 6 ÜBERGANG / MUTTENZERSTRASSE VERKEHRSKONZEPT 1 5 Post Schulstrasse 3 6a HAUPTSTRASSE/RHEINFELDERSTRASSE 5 21 Ab dem neuen Kreisel Schulstrasse bis zur Halte- RHEINFELDERSTRASSE (I) MUTTENZERSTRASSE 9c 1 2 BIRSFELDEN stelle Hard nutzen der Tram- und der Autoverkehr 3a Für eine stabile Abwicklung des Trambetriebs soll für Zur Optimierung des Verkehrsflusses wird die Birseck- Rheinstrasse 3 2 41 55a in Richtung Hard ein gemeinsames Mischtrassee, 1 2 55 das Tram Richtung Basel ein eigenes Trassee bis strasse direkt als T-Knoten mit LSA (Lichtsteuerungs- Die Haupt- bzw. Rheinfelderstrasse in Birsfelden ist eine 9b 15 Richtung Basel wird das Tram über ein Eigentrassee zum Knoten Schulstrasse realisiert werden. Dies anlage) in die Rheinfelderstrasse münden. ) erlaubt im Zusammenspiel mit der Lichtsteuerungs- kantonale Hauptverkehrsstrasse, die von bis zu 11’000 13 geführt. Somit ist das Tram nicht vom individuellen 1 anlage (LSA) Birseckstrasse/Muttenzerstrasse und der 1 Autoverkehr und Rückstau zwischen Knoten Fahrzeugen pro Tag befahren wird, zusätzlich wird die 11 ÖV-Priorisierung am Kreisel Schulstrasse, den Verkehr (Optiker) Gewerbelokal (Elektronik (Schuhmacher) Ladenlokal 45a Ladenlokal KITA 9 Birseckstrasse und Hard betroffen. 73c 73b im Zentrum flüssig zu halten. Damit wird ein zuver- Tramlinie Nr. 3 auf dieser Achse geführt. Die Strasse dient Bürogebäude (Kantonalbank) 1 3 lässiger Trambetrieb trotz Mischtrassee -

IWB Legionellen-Analyse

IWB WASSERLABOR Legionellen-Analyse gemäss Trink-, Bade- und Duschwasserverordnung. Aus eigener Energie. Mit Wasseranalysen in die Gesundheit Ihrer Kunden investieren Das IWB Wasserlabor untersucht Ihr Duschwasser hinsichtlich der gesetzlich geforderten Parameter gemäss Trink-, Bade- und Duschwasserverordnung TBDV und berät Sie, wie Sie die Qualität des Wassers langfristig hoch halten können. Ihre Vorteile • Einfach: Sie müssen sich um nichts kümmern. Wir beraten Sie vor Ort und organisieren die Logistik der Proben. Alles aus einer Hand. • Akkreditiert: Profitieren Sie von der langjährigen Erfahrung des akkredi- tierten IWB Wasserlabors in Wasser- analysen und Beratung. • Lokal: Wir holen die Proben ab. Die Messergebnisse Ihrer Proben sind durch die kurzen Transport- wege sehr zuverlässig. • Neutral: IWB ist keine Vollzugsbe- hörde und kann Sie deshalb neutral beraten. Daten werden nicht an Dritte weitergegeben. Wasser-Check Die Verantwortung für die Einhaltung der gesetzlich vorgeschriebenen Werte liegt beim Betreiber der Hausinstallation. Mit dem Wasser-Check bieten wir Ihnen ein umfangreiches Paket, um die Hygienesituation in Ihrem Gebäude zu analysieren. Der Wasser-Check beinhaltet • Terminvereinbarung mit Ansprechpartner vor Ort • Standortgespräch und Erstberatung • Factsheet mit wichtigen Tipps • Fachgerechte Erhebung repräsentativer Proben • Messung relevanter Parameter vor Ort (Temperatur etc.) • Frist- und fachgerechte Probenlogistik • Quantitative Analyse nach Vorgaben TBDV, Analyse Legionella spp. nach ISO 11731 • Unverzügliche -

Language Contact at the Romance-Germanic Language Border

Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Other Books of Interest from Multilingual Matters Beyond Bilingualism: Multilingualism and Multilingual Education Jasone Cenoz and Fred Genesee (eds) Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (eds) Bilingualism: Beyond Basic Principles Jean-Marc Dewaele, Alex Housen and Li wei (eds) Can Threatened Languages be Saved? Joshua Fishman (ed.) Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France Timothy Pooley Community and Communication Sue Wright A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism Philip Herdina and Ulrike Jessner Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Colin Baker and Sylvia Prys Jones Identity, Insecurity and Image: France and Language Dennis Ager Language, Culture and Communication in Contemporary Europe Charlotte Hoffman (ed.) Language and Society in a Changing Italy Arturo Tosi Language Planning in Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippines Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Planning in Nepal, Taiwan and Sweden Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. and Robert B. Kaplan (eds) Language Planning: From Practice to Theory Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Reclamation Hubisi Nwenmely Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Christina Bratt Paulston and Donald Peckham (eds) Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy Dennis Ager Multilingualism in Spain M. Teresa Turell (ed.) The Other Languages of Europe Guus Extra and Durk Gorter (eds) A Reader in French Sociolinguistics Malcolm Offord (ed.) Please contact us for the latest book information: Multilingual Matters, Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon, BS21 7HH, England http://www.multilingual-matters.com Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Language Contact at Romance-Germanic Language Border/Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns. -

Bericht Über Das Hochwasser

KANTONALER KRISENSTAB KKS BASEL-LANDSCHAFT BERICHT VOM 22.1.2009 ÜBER DAS HOCHWASSER VOM 8./9. AUGUST 2007 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Zusammenfassung......................................................................................................... 5 2. Ereignis, Auswirkungen und Schadenlage ..................................................................... 6 2.1. Niederschläge ........................................................................................................6 2.2. Abflüsse .................................................................................................................7 2.2.1. Birs................................................................................................................. 7 2.2.2. Birsig.............................................................................................................10 2.2.3. Ergolz / Frenke..............................................................................................10 2.3. Grundwasserpegel ...............................................................................................13 2.4. Schadenübersicht.................................................................................................14 3. Schadenlage .................................................................................................................16 3.1. Siedlungsgebiet....................................................................................................16 3.2. Landwirtschaftsgebiet...........................................................................................24 -

Die Pfarrbücher Des Kantons Solothurn

Die Pfarrbücher des Kantons Solothurn Autor(en): Herzog, Walter Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Der Schweizer Familienforscher = Le généalogiste suisse Band (Jahr): 30 (1963) Heft 3-4 PDF erstellt am: 24.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-697671 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch damals in kürzester Zeit fast ein Dutzend Ahnentafeln zusammen- zutragen, von denen sich aber knapp die Hälfte auswerten und im Vortrag benutzen ließen. Und ich schätze mich überaus glücklich, durch eine nette Geste eines weithinaus mit mir Verwandten vor Jahren in den Besitz einer Abschrift der Geschlechtsfolge Glutz von P. -

DORFBLATT 2021 Nr. 1 Februar

Wichtige Telefonnummern Gemeindeverwaltung Kirchen Rotbergstrasse 1, 4116 Metzerlen 061 731 15 12 Röm. kath. Kirche 061 731 15 20 Metzerlen-Mariastein [email protected] Di + Do 09.00 – 14.00 www.metzerlen.ch Susanne Wetzel: www.mariastein.ch P 061 731 20 58 www.metzerlen-mariastein.ch 061 731 38 86 Ev. Ref. Kirche, Flüh 061 735 11 11 Kloster Mariastein Schalteröffnungen Schule Metzerlen-Mariastein Montag 09.30 - 11.30 / 16.00 – 18.00 061 731 33 52 Kindergarten, Blauenweg 2 Dienstag 13.00 – 15.00 Freitag 09.30 – 11.30 061 731 21 50 Primarschule, Gemeindezentrum Termine auch nach telefonischer Vereinbarung Werkhof der Gemeinde 061 731 02 58 Primarschule, Rotbergstrasse 079 211 94 19 Linus Probst 061 731 21 84 Allmendhalle 079 612 40 97 Dominic Wetzel 061 735 95 51 Oberstufenzentrum Bättwil Notrufnummern Kindertagesstätte 112 Notrufnummer 061 731 33 75 Vogelnest, Rotbergstr. 8 117 Polizei Lebensmittel 061 704 71 40 Polizeiposten Mariastein 061 731 18 19 Dorflädeli Metzerlen 118 Feuerwehr Mi + Sa-Nachmittag geschl. 144 Sanität 061 735 11 90 Klosterladen Mariastein 1414 Rega Montag geschlossen 061 261 15 15 Ärztlicher Notfalldienst Früsch vom Buurehof 061 263 75 75 Notfall-Apotheke 061 731 27 76 Hofladen Brunnenhof 061 265 25 25 Unispital Basel Mo - Mi geschlossen 061 436 36 36 Bruderholzspital 061 731 23 36 Kulinarische Werkstatt 061 704 44 44 Spital Dornach 061 733 89 55 Klosterhof, Mariastein 061 415 41 41 Primeo Energie Hotline 079 282 31 32 Wildhüter (Christian Erb) Postagentur Forstbetrieb Am Blauen 061 731 18 19 im Dorflädeli „Fritz“ 061 731 11 16 Werkhof, Ettingen Tankstelle 079 426 11 23 Chr. -

International School Rheinfelden

INSIDE: YOUTH CHOIR FEST • STREET FOOD FEST • TEDX • SINFONIEORCHESTER BASEL • CITY SKATE • 3LÄNDERLAUF Volume 4 Issue 8 CHF 5 5 A Monthly Guide to Living in Basel May 2016 Circus is in the Air At academia we •Educate the whole individual: academically,socially, physically and emotionally •Nurturestudents to reach their full potential and pursue A cAsuAl excellence in everything they do ApproAch •Foster alove of learning and creativity to luxury •Develop compassionate global ambassadors •Emphasize team work and problem solving Preschool / Primary / Pre-College (K-8) •Bilingual Education (German/English) •Integrated Cambridge International Curriculum and Basel Stadt Curriculum College (9-12) AsK For A pErsoNAl AppoINtMENt. •High Quality Exam Preparation phoNE +41 79 352 42 12 · FrEIE strAssE 34, •Entry into Swiss and International Universities 4001 BAsEl · www. jANEtBArgEzI.coM Phone+41 61 260 20 80 www.academia-international.ch 2 Basel Life Magazine / www.basellife.com LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Readers, The Basel Life team would like to thank you for taking the time to share your fabulous feedback over the years. It has always been a welcome confir May 2016 Volume 4 Issue 8 mation that we have succeeded in our goal of sharing our passion and knowledge of Basel with you. From its humble beginnings almost four TABLE OF CONTENTS years ago, Basel Life Magazine has always endeavored to provide its read ers with timely information on events and activities in and around Basel, cultural and historical background information on important Swiss/Basel Events in Basel: May 2016 4–7 traditions and customs, practical tips for everyday life, as well as a wealth of other information, all at the cost of the printed material. -

150 Jahre Stift Olsberg

150 Jahre Stift Olsberg 150 Jahre Stift Olsberg Impressum Herausgeber: Kanton Aargau, Dep. BKS Satz und Druck: Herzog Medien AG, Rheinfelden Umschlag: Aufnahme Adi Tresch, 25.07.2006, Gasballonpilot Silvan Romer Fotos: Wenn nicht anders vermerkt: Stift Olsberg Auflage: 1200 Exemplare ©2010 bei den Autoren Inhalt Vorwort Alex Hürzeler . 7 Vorwort Urs Jakob . 8 Die Zisterzienserinnen vom Gottesgarten Jürg Andrea Bossardt . 13 Pädagogik und Bau im Wandel Joseph Echle-Berger Einleitung . 21 Die geographische Lage . 22 Die Liegenschaftspolitik des Kantons nach der Klosteraufhebung . 23 Das Klostergebäude in der Zwischennutzung . 26 Der Übergang von der privat geführten «Pestalozzistiftung der deutschen Schweiz» an das Erziehungsdepartement des Kantons Aargau . 37 Die Erziehungsanstalt Pestalozzistiftung und ihre Leiter von 1860–1942 . 42 Die Erziehungsanstalt wird zur «Staatlichen Pestalozzistiftung Olsberg» 1946 . 54 Die Staatliche Pestalozzistiftung Olsberg und ihre Leiter von 1955–1999 . 57 Die Staatliche Pestalozzistiftung Olsberg wird zum Stift Olsberg 2006 . 67 Heutiger Betrieb Urs Jakob . 75 Leitbild . 75 Schule / Sozialpädagogik . 77 Dienste – Spezialangebot / Ärztliche Beratung & Beratende Dienste . 78 Aufnahmekriterien / Aufnahmeverfahren . 78 Förderplanung . 80 Austritt/nach dem Austritt . 81 Führung / Mitarbeitende / Raumvermietungen und Führungen / Landwirtschaft / Ausblick . 82 Schlussbemerkung . 83 Die Sicht der Kulturhistorischen Schule auf Fragen der Erziehung Margarethe Liebrand . 87 5 6 Vorwort des Regierungsrates Liebe Leserin, -

Leitfaden Für Todesfälle Ra Tgeber Für Hinterbliebene

Leitfaden für Todesfälle Ra tgeber für Hinterbliebene Gemeindeverwaltung Bottmingen Inhalt Feststellung des Todes . 2 Anzeigepflicht . 2 Anordnungen für die Bestattung . 3 Bestattung . 3 Erdbestattung oder Kremation . 4 Aufbahrung . 4 Art der Grabstätten . 5 Trauerfeier / Abdankung . 6 Trauermahl . 6 Amtliche Publikation / Todesanzeige . 7 Wahl von Sarg oder Urne . 7 Gebühren / Kosten . 8 Grabmäler . 9 Grabpflege . 9 Erbrechtliches . 10 Folgende Stellen und Institutionen sind über den Tod zu informieren . 11 Kirchgemeinden . 12 Bestattungsinstitute . 12 Kontaktadressen . 13 Anfahrtsplan Friedhof Schönenberg . 14 Persönliche Notizen . 16 Umschlag innen/hinten . 1 Feststellung des Todes Anordnungen für die Bestattung Bei einem Todesfall ist unverzüglich der Die Art der Bestattung richtet sich nach den Anordnungen der verstorbenen behandelnde Arzt/die behandelnde Ärztin Person. Liegen keine Anord nungen vor, entscheiden die nächsten Hinter - oder ein Notfallarzt/eine Notfallärztin zu bliebenen, wie die Bestattung erfolgen soll. Ohne schriftliche Anordnung rufen. Er oder sie stellt die Todes be schei - und bestimmende Hinterbliebene findet eine Kremation mit Bestattung im nigung zuhanden des Zivil stands amtes aus. Gemeinschaftsgrab statt ( Aschebestattung) . Stirbt jemand im Spital, erhalten die Ange - hörigen eine Kopie der Todes bescheinigung für das Bestattungs büro der Gemeinde - verwaltung (Original geht an das zuständi - Bestattung ge Zivilstandsamt). Im Rahmen des Gesetzes kann jede Person frei bestimmen, wie sie bestattet werden möchte. Anzeigepflicht Wer sich für die Art seiner Bestattung ent - schieden hat, sollte dies in Form eines Stirbt eine Person an ihrem Wohnort , ist der Tod beim örtlichen Bestattungswunsches schriftlich festhalten Bestattungsbüro mit der ärztlichen Todes bescheinigung und einem Ausweis und die Angehörigen informieren. Der Be stat - (Pas s/ ID) unverzüglich zur Anzeige zu bringen. -

FEBRUAR 2020 Sand Hollow State Park, Utah, U.S.A

FEBRUAR 2020 Sand Hollow State Park, Utah, U.S.A. EDITORIAL Abo. Treffend ist, dass exakt in der Zeit Bei -10 ° C bilden sich von der Feuchtigkeit, die der See abgibt, an Liebe Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner der Feiertage Statistiken über die häu- den Pflanzen skurrile Eisgebilde. figste Todesursache in der Schweiz ver- In 11 Monaten ist Weihnachten. öffentlicht werden. Im Jahr 2017 starben Foto © Denise & Adrian Barth Aber vorher wollen wir uns über das neu immerhin 66‘971 Personen an Herz- begonnene 2020 freuen, ein gerades Kreislauf-Erkrankungen, was sich – wer Jahr, auch wenn der Februar wegen des hätte das gedacht – auf ungesunde Er- Schaltjahrs ungerade 29 Tage haben nährung und zu wenig Bewegung zu- wird. 2020 ist auch der Aufbruch in ein rückführen lässt. Natürlich nicht in allen neues Jahrzehnt, was uns beflügeln Fällen, jedoch ist es sicherlich nicht kann und uns zu neuen Ufern aufbre- falsch, die eigenen Gewohnheiten immer chen lässt. Glaubt man überdies der mal wieder zu überdenken. Unter Numerologie, dann ist es ein 4-er Jahr – www.witterswil.ch findet man unter Ge- denn 2+0+2+0=4. Und 4 ist eine stabile meinde – Vereine/Organisationen tolle Zahl, veranschaulicht durch einen Tisch Bewegungsangebote oder Ideen für ein mit 4 Beinen, die 4 Jahreszeiten oder ein neues Hobby. Wenn Sie nichts Passen- Die Sozialregion stellt sich vor Quadrat. des finden, gibt es aber keinen Grund zu verzagen: Die Lebenserwartung in der Nach der Schlemmerzeit der Festtage ist Schweiz hat zwischen 2007 und 2017 Mittwoch, 18. März um 19.30 Uhr der magere Januar nun schon Geschich- trotz allem um etwa 2 Jahre zugenom- Foyer des Oberstufenzentrums (OZL) in Bättwil te.