Women's Education Worldwide Student

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dia a Dia Sara Masó I Carme Tejeiro

DIA A DIA SARA MASÓ I CARME TEJEIRO NOVEMBRE 2001 solidaritat amb els Estats Units amb motiu dels Admira. Els responsables del grup assenyalen 2 DE NOVEMBRE terribles atemptats que ha sofert. Tampoc que "s'estudia la possibilitat d'entrar en suposa que modifiquem la nostra condició l'accionariat de la plataforma de televisió EL CAC ESPERA UNA BONA LLEI d'enemics expressos i frontals dels terroristes, digital Quiero» L'entrada a Quiero podria ser un PER A LA CCRTV de tots els terroristes, i del règim talibà que primer pas per a una unió entre Via Digital i El de president del Consell de l'Audiovisual protegeix Bin Laden." I conclou: "però no Canal Satélite Digital. Catalunya, Francesc Codina, manifesta no sen¬ podem acceptar que la lògica actuació contra tir-se preocupat pel retard que afecta aquest adversari es faci amb bombardeigs que POLÈMICA JUDICIAL PER UNA l'aprovació de la nova Llei de la Corporació afecten una població civil no responsable de INDEMNITZACIÓ A PREYSLER Catalana de Ràdio i Televisió (CCRTV) sempre les decisions del fonamentalisme que ha Una denúncia d'Isabel Preysler contra la revista que el resultat final ofereixi "un bon projecte" i conquistat el poder en el país." Lecturas ha causat polèmica entre el Tribunal la normativa aprovada "sigui bona". La Comissió Suprem i el Constitucional. Un article de la revis¬ Parlamentària per a la reforma de l'esmentada KABUL ALLIBERA EL PERIODISTA ta havia publicat que Preysler tenia "grans a la llei no s'ha reunit des d'abans de l'estiu. DE PARIS MATCH cara". -

Pera,Undiscorsocontrocasini

ARRETRATI L IRE 3.000 – EURO 1.55 SPEDIZ. IN ABBON. POST. 45\% anno 78 n.235 martedì 20 novembre 2001 lire 1.500 (euro 0.77) www.unita.it ART. 2 COMMA 20/B LEGGE 662/96 – FILIALE DI ROMA «Il silenzio è pesante e sinistro. Osama. Ma certo qualcuno Al Qaeda». Dall’ultimo articolo Non siamo neanche sicuri che è passato di qui dopo di Maria Grazia Cutuli, l’area sia libera dagli arabi di la partenza dei membri di Corriere della Sera, 19 novembre Il primo caduto italiano è una giornalista Maria Grazia Cutuli, del Corriere della Sera, uccisa in Afghanistan insieme a quattro colleghi Aveva scoperto fiale di gas nervino in una base di Al Qaeda appena abbandonata dai taleban DALL’INVIATO Gabriel Bertinetto America ITA REVE QUETTA Hanno bloccato la macchi- V B na, li hanno fatti scendere, poi li han- L’ECONOMIA no finiti a colpi di kalashnikov: quat- DI UNA REPORTER tro reporter, un interprete. Tra di lo- ro Maria Grazia Cutuli, 39 anni, in- NELLA PALUDE ORAGGIOSA viata del «Corriere della Sera». Erano C in viaggio da Jalalabad a Kabul, lun- DELLA POLITICA aria Grazia Cutuli, inviato del go una strada terra di nessuno. Insie- «Corriere della Sera» è il primo me alla nostra collega sono rimasti Robert Reich M caduto italiano nella guerra del- uccisi anche l’inviato di «El Mundo», l’Afghanistan. Ma lei non era in guerra. Julio Fuentes, un cameraman della Non aveva armi. Non faceva parte di un Reuters, un fotogrago afghano e un uasi tutti concordano sul fatto contingente e nessuno le copriva le spalle. -

Womenonthefrontlines

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2018 Annual Edition DATELINE #womenonthefrontlines DATELINE 2018 1 A person throws colored powder during a Holi festival party organized by Jai Jai Hooray and hosted by the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Brooklyn, New York, U.S., March 3, 2018. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly A person throws colored powder during a Holi festival party organized by Jai Jai Hooray and hosted by the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Brooklyn, New York, U.S., March 3, 2018. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly A person throws colored powder during a Holi festival party organized by Jai Jai Hooray and hosted by the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Brooklyn, New York, U.S., March 3, 2018. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly Reuters congratulates Reutersthe winners congratulates of the 2017 Overseas Press Club Awards. the winners of the 2017 Overseas Press Club Awards. OverseasWe are proud to Press support theClub Overseas Awards. Press Club and its commitment to excellence in international journalism. We are proud to support the Overseas Press Club and its commitmentWe are proud toto excellencesupport the in Overseas international Press journalism. Club and its commitment to excellence in international journalism. 2 DATELINE 2018 President’s Letter / DEIDRE DEPKE n the reuters memorial speech delivered at Oxford last February – which I urge Iyou all to read if you haven’t – Washington Post Editor Marty Baron wondered how we arrived at the point where the public shrugs off demonstrably false statements by public figures, where instant in touch with people’s lives. That address her injuries continues websites suffer no consequences is why ensuring the accuracy of to report from the frontlines in for spreading lies and conspiracy sources and protecting communi- Afghanistan. -

Stampa Nel Mirino

The Bronx Journal/December 2001 B 2 I TA L I A N STAMPA NEL MIRINO MARA PALERMO Bronx Journal Staff Reporter rima vittima italiana in Afghanistan, e non è un soldato. Si tratta di Maria probabilmente dovute secondo gli esperti, con cui aveva pure Grazia Cutuli, 39 anni, giornalista alla caduta del corpo per terra. Questo è collaborato. Da qui del Corriere della Sera, inviata italiana che quanto emerge dall'esame del cadavere ese- il trasferimento a ha perso la vita il 19 novembre. guito dai medici legali dell'Università La Milano per la Maria Grazia Cutuli si trovava in un con- Sapienza incaricati di stabilire le cause scuola di giornalis- voglio con altri giornalisti su una strada che della morte della giornalista. mo. Nel capoluogo collega Jalalabad a Kabul. Secondo “Potrebbe essere stata un’esecuzione sim- lombardo aveva Edoardo San Juan, giornalista della televi- bolica contro l'Occidente o una rapina…” continuato la sione catalana Tv3, la Cutuli avrebbe deciso dice Mario Cutuli, fratello Maria Grazia. gavetta nel gior- all'ultimo momento di lasciare Jalalabad L’uomo rivela infatti dei particolari inqui- nale Centocose. alla volta della capitale afghana. San Juan, etanti che potrebbero avvalorare le sue Da lì il salto di si trovava nello stesso convoglio ma su ipotesi. Per esempio, al giornalista spagno- qualità ad Epoca un’altra vettura. L’inviata italiana era nella lo Julio Fuentes sembra sia stata amputata ed infine al macchina che guidava la colonna mentre una mano, mentre a Maria Grazia, una parte Corriere della Edoardo San Juan si trovava in fondo al del lobo dell'orecchio destro. -

Freedom of Expression & Impunity Campaign

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION & IMPUNITY CAMPAIGN CHALLENGING IMPUNITY: A PEN REPORT ON UNPUNISHED CRIMES AGAINST WRITERS AND JOURNALISTS PEN Club de México PROLOGUE The year-long Campaign on Freedom of Expression and Impunity, focusing on unsolved and unpunished crimes aimed at silencing writers and journalists, was launched on November 25, 2002, in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, during a conference of the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) of International PEN. Direct actions have been taken throughout the year and culminated with the release of this PEN report on the problem of impunity and a roundtable during International PEN’s 69th World Congress of Writers in Mexico in November 2003. Please visit http://www.pencanada.ca/impunity/index.html. The campaign was led by PEN Canada and found partners in the Writers in Prison Committee of International PEN, PEN American Center and PEN Mexico. Thanks to all who took part. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Country profiles: Colombia 5 Iran 6 Mexico 7 Philippines 8 Russia 9 Writers & journalists killed since 1992 10 PEN recommendations and advocacy 14 Resources on impunity 18 Impunity Watch 20 1 “Through my experience as co-plaintiff in the on-going trial to resolve the murder of my sister, Myrna Mack, I have seen impunity up close, along every step of this tortuous path in search of justice. I have felt it when essential information has been denied that would determine individual criminal responsibility; when judges and witnesses have been threatened; when the lawyers for the accused military officials use the same constitutional guarantees of due process in order to obstruct judicial procedures; and when my family, my lawyers, my colleagues and I have been threatened or been victims of campaigns to discredit us. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17673 – 7,90 F - 1,20 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE -- MERCREDI 21 NOVEMBRE 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI M. Jospin en difficulté Le nouveau désordre afghan b a La popularité Seigneurs de la guerre et factions rivales plongent certaines régions de l’Afghanistan dans du premier ministre l’insécurité et le chaos b Notre reportage dans la région de Jalalabad où quatre autres journalistes en forte baisse ont été tués b Britanniques et Français se heurtent à l’Alliance du Nord pour déployer leurs soldats dans les sondages SOMMAIRE b Le conflit et ses répercussions : L’ Europe lie son soutien financier b La guerre contre Al-Qaida : Qua- à la mise en place d’un régime a tre journalistes ont été tués, selon « légitime et multiethnique ». Les Les intentions leur chauffeur, lundi 19 novembre, Quinze veulent combler les lacunes sur la route reliant Jalalabad à de la défense européenne. Six pays de vote restent Kaboul. Le désordre règne dans européens travaillent en commun cette région livrée aux querelles sur un nouveau système d’armes. favorables entre seigneurs de la guerre. Des Nouvelle révolte de musulmans AFP à Jacques Chirac poches de résistance parsèment le dans le sud des Philippines. Selon ENQUÊTE pays. Le reportage de notre les prévisions de l’OCDE, le chôma- envoyé spécial à Jalalabad, Patrice ge continuera d’augmenter en Claude. Les talibans tiennent enco- 2002, la demande intérieure chute- L’arme a Insécurité, chômage, re Kunduz, dans le nord-est de ra et la croissance faiblira. p. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #128

#128 28 Nov 2001 USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Air University Air War College Maxwell AFB, Alabama Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. This information includes articles, papers and other documents addressing issues pertinent to US military response options for dealing with nuclear, biological and chemical threats and attacks. It’s our hope this information resource will help enhance your counterproliferation issue awareness. Established here at the Air War College in 1998, the USAF/CPC provides education and research to present and future leaders of the Air Force, as well as to members of other branches of the armed services and Department of Defense. Our purpose is to help those agencies better prepare to counter the threat from weapons of mass destruction. Please feel free to visit our web site at www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm for in-depth information and specific points of contact. Please direct any questions or comments on CPC Outreach Journal to Lt Col Michael W. Ritz, ANG Special Assistant to Director of CPC or Jo Ann Eddy, CPC Outreach Editor, at (334) 953-7538 or DSN 493-7538. To subscribe, change e-mail address, or unsubscribe to this journal or to request inclusion on the mailing list for CPC publications, please contact Mrs. Eddy. The following articles, papers or documents do not necessarily reflect official endorsement of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or other US government agencies. -

Journalism, Civil Liberties and the War on Terrorism

International Federation of Journalists Journalism, Civil Liberties And The War on Terrorism Final Report on The Aftermath of September 11 And the Implications for Journalism and Civil Liberties By Aidan White, General Secretary Introduction In the days immediately following the September 11th 2001 attacks on the United States, the IFJ carried out a brief survey of its member organisations seeking information about the immediate impact of the terrorist attacks. The report, to which journalists’ groups in 20 countries responded, was published on October 23rd 2001 and revealed fears of a fast- developing crisis for journalism and civil liberties. Some eight months later, these fears have been confirmed. The declaration of a “war on terrorism” by the United States and its international coalition has created a dangerous situation in which journalists have become victims as well as key actors in reporting events. This is war of a very different kind. There is no set piece military confrontation. There is no clearly defined enemy, no hard-and-fast objective, and no obvious point of conclusion. Inevitably, it has created a pervasive atmosphere of paranoia in which the spirit of press freedom and pluralism is fragile and vulnerable. It has also led to casualties among journalists and media staff. The brutal killing of Daniel Pearl in Pakistan at the start of the year, chillingly filmed by his media-wise murderers, has come to symbolise the appalling consequences of September 11 for journalism and for freedom of expression. That murder, together with the earlier killing of Marc Brunereau, Johanne Sutton, Pierre Billaud, Volker Handloik, Azizullah Haidari, Harry Burton, Julio Fuentes, Maria Grazia Cutuli and 1 Ulf Strömberg in Afghanistan, is a grim indicator of the dangers facing journalists. -

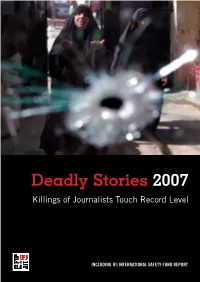

Deadly Stories 2007: Killings of Journalists Touch Record Level

Deadly Stories 2007 Killings of Journalists Touch Record Level INCLUDING IFJ INTERNATIONAL SAFETY FUND REPORT No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. The contents of this book are copyrighted and the rights to use of contributions rests with the authors themselves. Cover image: RNPS PICTURES OF THE YEAR. One of the last pictures taken by Reuters Iraqi photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen before he was killed on July 12, 2007 shows two old women dressed in black walking towards a window pierced by a bullet in the al-Amin al- Thaniyah neighbourhood of Baghdad. U.S. soldiers took Noor-Eldeen’s two digital cameras from the scene after he was killed. REUTERS/Namir Noor-Eldeen (IRAQ) Publisher: Aidan White, IFJ General Secretary Managing Editor: Rachel Cohen, IFJ Communications Officer Design: Mary Schrider, [email protected] Printed by Druk. Hoeilaart, Belgium The IFJ would like to thank Reuters, Anadolu Ajansi, the Oakland Tribune, and its member unions for contributing photos to this publication. Published in Belgium by the International Federation of Journalists © 2008 International Federation of Journalists International Press Centre Residence Palace, Block C 155 rue de la Loi B - 1040 Brussels Belgium Contents Deadly Stories 2007 ...........................................................................................................2 Journalists and media staff killed in 2007 ........................................................................4 The Year in Focus: IFJ Africa -

PERSONAL NOTE Kurt Schork, an Inspirational Reuters Journalist

PERSONAL NOTE Kurt Schork, an inspirational Reuters journalist who I worked with in East Timor, was shot dead in an ambush in Sierra Leone in May 2000 along with Miguel Gil Moreno de Mora of Associated Press Television; two other Reuters colleagues survived the ambush after a harrowing escape. I learned a huge amount during the few weeks I worked with Kurt as part of the Reuters team in Dili, based in a flooded and partially burned ground-floor room of the Hotel Turismo. He always behaved with disarming humility and respect, as a colleague and an equal, when in fact he was a legend and I was a clueless rookie. I found out he was dead when I sat down at my desk in Reuters Jakarta and saw that one of his most famous stories from Sarajevo had been reissued that day on Reuters screens; wondering why, I clicked on the headline to read the story, and then I knew. Harry Burton, an Australian journalist and cameraman who was a much loved member of the Jakarta bureau and also worked with us in East Timor, and Azizullah Haidari, a brave and witty Afghan colleague who I worked with in Pakistan, were killed on a stretch of highway between Jalalabad and Kabul in November 2001. A gang of armed bandits tried to halt a convoy of media vehicles heading for the Afghan capital, and managed to force one car to stop. Harry and Aziz were in that car, along with Maria Grazia Cutuli of Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, and Julio Fuentes of Spain's El Mundo. -

Authorization Document Maria Grazia Cutuli Primary School

Wienerberger Brick Award 2014 Bitte senden Sie alle Unterlagen bis spätestens 20. mai 2013, bevorzugt digital an [email protected]. Bilder und Pläne via Download-Link, ftp etc. Bitte kontaktieren Sie uns, wenn Sie die Unterlagen über unsere Mediendatenbank hochladen möchten. Please send all material until May 20 2013 at the latest, preferably by email to [email protected]. Pictures and plans via download-link, ftp etc. Please contact us if you want to use our Mediadatabase for uploading files. Postalische Unterlagen an: Material per post to: Wienerberger AG Marion Göth Wienerbergstraße 11, Wienerberg City 1100 Wien Austria Ihre wichtigsten Daten / Your Basic Information Architekturbüro / Firmenbezeichnung 2A+P/A (Gianfranco Bombaci, Matteo Costanzo), IaN+ (Carmelo Baglivo, Architect / Company name Luca Galofaro, Stefania Manna), ma0/emmeazero (Ketti Di Tardo, Alberto Jacovoni, Luca La Torre) and Mario Cutuli Kurzform des Architekturbüros zur Veröffentlichung im Buch brick‘14 2A+P/A, IaN+, ma0 and Mario Cutuli Short Version Architect for publishing in book brick‘14 Straße Via Tarvisio, 2 Street PLZ / Ort 00198 / Rome Post Code / City Land Italy Country Webseite www.2ap.it; www.ianplus.it; www.ma0.it Website Ansprechpartner Stefania Manna Contact Person Telefonnummer mit Durchwahl +39.329.2293183 Phone number and extension E-Mail [email protected] E-mail Wienerberger AG, A-1100 Wien, Wienerberg City, Wienerbergstraße 11 T +43 (1) 60 192-0, F +43(1) 60 192-10425 | www.brick14.com | www.wienerberger.com Wienerberger Brick Award 2014 Baudaten / Building Information Projektbezeichnung Maria Grazia Cutuli Primary School Project name Standort Kush Rot Village, Injil District, Herat, Afghanistan Location Fertigstellungsjahr April 2011 Completion Date Bauzeit June 2010 – April 2011 Building Time Nutzung Primary school as 'sign of peace', named after Maria Grazia Cutuli, a prominent Italian journalist who Building’s Purpose was murdered in Afghanistan in 2001, to commemorate 10 years from her death. -

Algerije Weer Eerbetoon Yannick Hiwat

Speciale uitgave 20 jaar BKB / Vrijdag 6 september 2019 / Amsterdam UITDAGERS VAN DE MACHT! De Chinese conceptueel kunstenaar, politiek activist en filosoof; Ai Weiwei. Foto: Ai Weiwei Studio CC DOOR MAARTEN VAN HEEMS, BKB In 2008 organiseerde BKB met be- de deur tonen, ze moeten er zelf door- genoeg om zelf actie te voeren, je moet te kijken. Trouwens ook naar de navel vriende activisten een groot festival heen gaan. ook andere mensen aanzetten tot ac- van de buurman en wat daar dan niet voor de Tibetaanse zaak op de NDSM- tie. In de vragen die BKB krijgt wordt aan deugt. werf in Amsterdam. Met 10.000 man Niet iedereen stond te applaudisseren. dit olievlekwerking genoemd. Dit soort grepen we de Olympische Spelen in Ik herinner me een telefoontje naar olievlekken zijn wel populair. Deze krant is een pamflet. Met één Beijing aan om aandacht te vragen kantoor waarom we geen festival orga- Niet veel later werden Twitter en Fa- boodschap: haal je neus uit die navel en voor de boodschap van de Dalai Lama niseerden om aandacht te vragen voor cebook geboren en nam het Do It Your- verander de wereld. (Her)ontdek jezelf van geweldloos verzet tegen onder- Myanmar. Daar was het allemaal nog self principe, uit de punkbeweging, een als activist. Er is nog genoeg te doen. drukking. Een jaar later werd hij uit- veel erger. Wij vroegen: waarom doe jij grote vlucht. Er ontstonden eindeloos genodigd in de Tweede Kamer. Die er het zelf niet? Daarop bleef het stil. Aan veel eenmanslegers voor evenzoveel daarna weinig mee deed, maar dat de andere kant van de lijn, maar ook doelen.