PERSONAL NOTE Kurt Schork, an Inspirational Reuters Journalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq Index Tracking Variables of Reconstruction & Security in Post-Saddam Iraq

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Tel: 202-797-6000 Fax: 202-797-6004 www.brooking s.edu Iraq Index Tracking Variables of Reconstruction & Security in Post-Saddam Iraq www.brookings.edu/iraqindex Updated October 31, 2005 For full source information for entries other than the current month, please see the Iraq Index archives at www.brookings.edu/fp/saban/iraq/indexarchive.htm Michael E. O’Hanlon Nina Kamp For more information please contact Nina Kamp at [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Security Indicators Page U.S. Troop Fatalities since March 2003…….……………………………………………………………....…………………………………………………4 Cause of Death for US Troops…………………………………………………………...…………………………………………………………………….5 American Military Fatalities by Category……………………………………………………………………….….……………………………….……….6 Geographic Distribution of Military Fatalities……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 U.S. Troops Wounded in Action since March 2003……………………………..…………….…………………………………….………………………..7 British Military Fatalities since March 2003………………………………….……………….…………………….............................................................7 Non-U.S. & U.K. Coalition Military Fatalities since March, 2003……………..….…………………….…………………………….…………...………..8 Non-U.S. & U.K. Coalition Military Fatalities by Country since March 2003…….…………………………………………………………...…………..8 Iraqi Military and Police Killed since January 2005…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……..9 Estimates of Iraqi Civilians Killed Since the Start of the War …………………………………………………………….…………………………….…9 -

The United States and Democracy Promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the Aftermath of the Events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War

The United States and democracy promotion in Iraq and Lebanon in the aftermath of the events of 9/11 and the 2003 Iraq War A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD. in Political Science. By Abess Taqi Ph.D. candidate, University of London Internal Supervisors Dr. James Chiriyankandath (Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) Professor Philip Murphy (Director, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London) External Co-Supervisor Dr. Maria Holt (Reader in Politics, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Westminster) © Copyright Abess Taqi April 2015. All rights reserved. 1 | P a g e DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: ………………………………………. Date: ……………………………………………. 2 | P a g e Abstract This thesis features two case studies exploring the George W. Bush Administration’s (2001 – 2009) efforts to promote democracy in the Arab world, following military occupation in Iraq, and through ‘democracy support’ or ‘democracy assistance’ in Lebanon. While reviewing well rehearsed arguments that emphasise the inappropriateness of the methods employed to promote Western liberal democracy in Middle East countries and the difficulties in the way of democracy being fostered by foreign powers, it focuses on two factors that also contributed to derailing the U.S.’s plans to introduce ‘Western style’ liberal democracy to Iraq and Lebanon. -

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

Dia a Dia Sara Masó I Carme Tejeiro

DIA A DIA SARA MASÓ I CARME TEJEIRO NOVEMBRE 2001 solidaritat amb els Estats Units amb motiu dels Admira. Els responsables del grup assenyalen 2 DE NOVEMBRE terribles atemptats que ha sofert. Tampoc que "s'estudia la possibilitat d'entrar en suposa que modifiquem la nostra condició l'accionariat de la plataforma de televisió EL CAC ESPERA UNA BONA LLEI d'enemics expressos i frontals dels terroristes, digital Quiero» L'entrada a Quiero podria ser un PER A LA CCRTV de tots els terroristes, i del règim talibà que primer pas per a una unió entre Via Digital i El de president del Consell de l'Audiovisual protegeix Bin Laden." I conclou: "però no Canal Satélite Digital. Catalunya, Francesc Codina, manifesta no sen¬ podem acceptar que la lògica actuació contra tir-se preocupat pel retard que afecta aquest adversari es faci amb bombardeigs que POLÈMICA JUDICIAL PER UNA l'aprovació de la nova Llei de la Corporació afecten una població civil no responsable de INDEMNITZACIÓ A PREYSLER Catalana de Ràdio i Televisió (CCRTV) sempre les decisions del fonamentalisme que ha Una denúncia d'Isabel Preysler contra la revista que el resultat final ofereixi "un bon projecte" i conquistat el poder en el país." Lecturas ha causat polèmica entre el Tribunal la normativa aprovada "sigui bona". La Comissió Suprem i el Constitucional. Un article de la revis¬ Parlamentària per a la reforma de l'esmentada KABUL ALLIBERA EL PERIODISTA ta havia publicat que Preysler tenia "grans a la llei no s'ha reunit des d'abans de l'estiu. DE PARIS MATCH cara". -

The War Correspondent

The War Correspondent The War Correspondent Fully updated second edition Greg McLaughlin First published 2002 Fully updated second edition first published 2016 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Greg McLaughlin 2002, 2016 The right of Greg McLaughlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3319 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3318 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1758 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1760 6 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1759 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the European Union and United States of America Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 PART I: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 2 The War Correspondent: Risk, Motivation and Tradition 9 3 Journalism, Objectivity and War 33 4 From Luckless Tribe to Wireless Tribe: The Impact of Media Technologies on War Reporting 63 PART II: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND THE MILITARY 5 Getting to Know Each Other: From Crimea to Vietnam 93 6 Learning and Forgetting: From the Falklands to the Gulf 118 7 Goodbye Vietnam Syndrome: The Embed System in Afghanistan and Iraq 141 PART III: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND IDEOLOGICAL FRAMEWORKS 8 Reporting the Cold War and the New World Order 161 9 Reporting the ‘War on Terror’ and the Return of the Evil Empire 190 10 Conclusions: ‘Telling Truth To Power’ – the Ultimate Role of the War Correspondent? 214 1 Introduction William Howard Russell is widely regarded as one of the first war cor- respondents to write for a commercial daily newspaper. -

New War Journalism Trends and Challenges

10.1515/nor-2017-0141 Nordicom Review 30 (2009) 1, pp. 95-112 New War Journalism Trends and Challenges STIG A. NOHRSTEDT Abstract How has war journalism changed since the end of the Cold War? After the fall of the Ber- lin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was talk of a new world order. The Balkan Wars of the 1990s gave rise to the concept of “new wars”. The 1990-91 Gulf War was the commercial breakthrough for the around-the-clock news chan- nel CNN, and the war in Afghanistan in 2001 for its competitor al-Jazeera. The 2003 Iraq war saw Internet’s great breakthrough in war journalism. A new world order, new wars, and new media – what impact is all this having on war journalism? This article outlines some important trends based on recent media research and discusses the new challenges as well as the consequences they entail for the conditions of war journalism, its professional reflexivity and democratic role. Keywords: new media war; propaganda and war journalism; framing of war news; visual war reporting; media reflexivity. Introduction How has war journalism changed since the end of the Cold War? After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, there was talk of a new world order holding the promise of international justice and peace. However, the Balkan Wars of the 1990s gave rise to the concept of “new wars” that in the wake of the terror attacks of 9/11 have acquired an iconicity rivalling that of fiction films. -

War and Media: Constancy and Convulsion

Volume 87 Number 860 December 2005 War and media: Constancy and convulsion Arnaud Mercier* Arnaud Mercier is professor at the university Paul Verlaine, Metz (France) and director of the Laboratory “Communication and Politics” at the French National Center for Scientifi c Research (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifi que, CNRS). Abstract To consider the relationship between war and the media is to look at the way in which the media are involved in conflict, either as targets (war on the media) or as an auxiliary (war thanks to the media). On the basis of this distinction, four major developments may be cited that today combine to make war above all a media spectacle: photography, which opened the door to manipulation through stage-management; live technologies, which raise the question of journalists’ critical distance vis-à-vis the material they broadcast and which can facilitate the process of using them; pressure on the media and media globalization, which have led to a change in the way the political and military authorities go about making propaganda; and, finally, the fact that censorship has increasingly come into disrepute, which has prompted the authorities to think of novel ways of controlling journalists. : : : : : : : The military has long integrated into its operational planning the principles of the information society and of a world wrapped into a tight network of infor- mation media. Controlling the way war is represented has acquired the same strategic importance as the ability to disrupt the enemies’ communications.1 The “rescue” of Private Jessica Lynch, which was filmed by the US Army on 1 April 2003, is a textbook example, even if the lies surrounding Private Lynch’s * This contribution is an adapted version of the article “Guerre et médias: permanences et mutations”, Raisons politiques, N° 13, février 2004, pp. -

Visiting Iraq

Visiting Iraq How to apply for a business visa Applications for business visas should be made at the Iraqi Consulate prior to departure. Consular officials at the Iraqi Embassy have indicated that visa approval can take two to six weeks from the date of submission. Visas are issued to business people, provided that they have official invitations from Iraqi authorities or are introduced as such by their respective Ministries of Foreign Affairs and are supplied with letters from the Chamber of Commerce. Applicants should also submit a letter of request from their own company stating the reason for their travel. How to travel to Iraq There are a growing number of commercial airline flights from Europe and the U.S. to Iraq's main cities. Baghdad Airline Destinations Bahrain Air Bahrain Cham Wings Airlines Damascus Flying Carpet Beirut Gulf Air Bahrain Gryphon Airlines Kuwait Iraqi Airways Amman, Bahrain, Basrah, Beirut, Cairo, Damascus, Doha, Dubai, Düsseldorf, Erbil, Frankfurt, Istanbul-Atatürk, Jeddah, Karachi, Malmö, Mosul, Najaf, Stockholm-Arlanda, Sulaymaniyah, Tehran-Imam Khomeini Jupiter Airlines Dubai Mahan Air Tehran-Imam Khomeini Middle East Airlines Beirut Royal Jordanian Amman Turkish Airlines Istanbul-Atatürk Erbil Airlines Destinations Atlasjet Istanbul-Atatürk Austrian Airlines Vienna Gulf Air Bahrain Iraqi Airways Baghdad, Basrah, Beirut, Oman, Stockholm-Arlanda, Sulaymaniyah, Tehran Imam Khomeini Jupiter Airlines Dubai Vision Air International Dubai Royal Jordanian Amman Viking Airlines Stokholm-Arlanda, Birmingham Basrah Airlines Destinations AVE.com Sharjah Jupiter Airlines Dubai Iraqi Airways Amman, Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, Dubai, Erbil, Oman, Sulaymaniyah MCA Airlines Stockholm Royal Jordanian Amman Turkish Airlines Istanbul Mosul Airlines Destinations Iraqi Airways Baghdad, Dubai Jupiter Airlines Dubai, Istanbul Royal Jordanian Airlines Amman Frequency or availability of flights are subject to change. -

Pera,Undiscorsocontrocasini

ARRETRATI L IRE 3.000 – EURO 1.55 SPEDIZ. IN ABBON. POST. 45\% anno 78 n.235 martedì 20 novembre 2001 lire 1.500 (euro 0.77) www.unita.it ART. 2 COMMA 20/B LEGGE 662/96 – FILIALE DI ROMA «Il silenzio è pesante e sinistro. Osama. Ma certo qualcuno Al Qaeda». Dall’ultimo articolo Non siamo neanche sicuri che è passato di qui dopo di Maria Grazia Cutuli, l’area sia libera dagli arabi di la partenza dei membri di Corriere della Sera, 19 novembre Il primo caduto italiano è una giornalista Maria Grazia Cutuli, del Corriere della Sera, uccisa in Afghanistan insieme a quattro colleghi Aveva scoperto fiale di gas nervino in una base di Al Qaeda appena abbandonata dai taleban DALL’INVIATO Gabriel Bertinetto America ITA REVE QUETTA Hanno bloccato la macchi- V B na, li hanno fatti scendere, poi li han- L’ECONOMIA no finiti a colpi di kalashnikov: quat- DI UNA REPORTER tro reporter, un interprete. Tra di lo- ro Maria Grazia Cutuli, 39 anni, in- NELLA PALUDE ORAGGIOSA viata del «Corriere della Sera». Erano C in viaggio da Jalalabad a Kabul, lun- DELLA POLITICA aria Grazia Cutuli, inviato del go una strada terra di nessuno. Insie- «Corriere della Sera» è il primo me alla nostra collega sono rimasti Robert Reich M caduto italiano nella guerra del- uccisi anche l’inviato di «El Mundo», l’Afghanistan. Ma lei non era in guerra. Julio Fuentes, un cameraman della Non aveva armi. Non faceva parte di un Reuters, un fotogrago afghano e un uasi tutti concordano sul fatto contingente e nessuno le copriva le spalle. -

Womenonthefrontlines

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2018 Annual Edition DATELINE #womenonthefrontlines DATELINE 2018 1 A person throws colored powder during a Holi festival party organized by Jai Jai Hooray and hosted by the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Brooklyn, New York, U.S., March 3, 2018. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly A person throws colored powder during a Holi festival party organized by Jai Jai Hooray and hosted by the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Brooklyn, New York, U.S., March 3, 2018. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly A person throws colored powder during a Holi festival party organized by Jai Jai Hooray and hosted by the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Brooklyn, New York, U.S., March 3, 2018. REUTERS/Andrew Kelly Reuters congratulates Reutersthe winners congratulates of the 2017 Overseas Press Club Awards. the winners of the 2017 Overseas Press Club Awards. OverseasWe are proud to Press support theClub Overseas Awards. Press Club and its commitment to excellence in international journalism. We are proud to support the Overseas Press Club and its commitmentWe are proud toto excellencesupport the in Overseas international Press journalism. Club and its commitment to excellence in international journalism. 2 DATELINE 2018 President’s Letter / DEIDRE DEPKE n the reuters memorial speech delivered at Oxford last February – which I urge Iyou all to read if you haven’t – Washington Post Editor Marty Baron wondered how we arrived at the point where the public shrugs off demonstrably false statements by public figures, where instant in touch with people’s lives. That address her injuries continues websites suffer no consequences is why ensuring the accuracy of to report from the frontlines in for spreading lies and conspiracy sources and protecting communi- Afghanistan. -

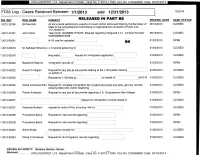

Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 RELEASED IN

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2013-17945 Doc No. C05494608 Date: 04/16/2014 FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 1/2/2014 tEQ REF REQ_NAME SUBJECT RELEASED IN PART B6 RECEIVE DATE CASE STATUS 2012-26796 Bill Marczak All documents pertaining to exports of crowd control items submitted by the Secretary of 08/14/2013 CLOSED State to the Congressional Committees on Appropriations pursuant to Public Law 112-74042512 2012-31657 John Calvit Task Order: SAQMMA11F0233. Request regarding Vanguard 2.2.1. Contract Number: 08/14/2013 CLOSED GS00Q09BGF0048 L-2013-00001 H-1B visa for requester B6 01/02/2013 OPEN 2013-00078 M. Kathleen Minervino J-1 records pertaining to 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00218 Requestor request for immigration application 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00220 Bashist M Sharma immigration records of 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00222 Robert D Ahlgren Request for any and all documents relating to the 1-130 petition filed by 01/02/2013 CLOSED on behalf of F-2013-00223 Request for 1-130 filed 1.)- on behalf of NVC # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00224 Gloria Contreras Edin Request for complete immigration file including all entries and exits, and any records 01/02/2013 CLOSED showing false USC claims regarding F-2013-00226 Parker Anderson Request for any and all documents regarding U.S. Congressman Sam Steiger. 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00227 request for immigration records receipt # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00237 Kayleyne Brottem request for entire A-File, including 1-94 for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00238 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00239 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00242 Sonia Alcala Immigration records for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00243 Gloria C Cardenas Request for all immigration records regarding 01/02/2013 CLOSED REVIEW AUTHORITY: Barbara Nielsen, Senior Reviewer UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

Dangerous Occupation

Dangerous Occupation The Vulnerabilities of Journalists Covering a Changing World By Joel Simon wenty years ago, most people got their international news from relatively well- established foreign correspondents working for agencies, broadcast outlets, and Tnewspapers. Today, of course, the process of both gathering and disseminat- ing news is more diffuse. This new system has some widely recognized advantages. It democratizes the information-gathering process, allowing participation by more people from different backgrounds and perspectives. It opens the media not only to “citizen journalists” but also to advocacy and civil society organizations including human rights groups that increasingly provide firsthand reporting in war-ravaged societies. New infor- mation technologies allow those involved in collecting news to communicate directly with those accessing the information. The sheer volume of people participating in this process challenges authoritarian models of censorship based on hierarchies of control. But there are also considerable weaknesses. Freelancers, bloggers, and citizen jour- nalists who work with few resources and little or no institutional support are more vulnerable to government repression. Emerging technologies cut both ways, and auto- cratic governments are developing new systems to monitor and control online speech that are both effective and hard to detect. The direct links created between content producers and consumers make it possible for violent groups to bypass the traditional media and reach the public via chat rooms and websites. Journalists have become less essential and therefore more vulnerable as a result. Many predicted that the quantity, quality, and fluid- w American journalist ity of information would inherently increase as time went James Foley covering the on and technology improved, but this has not necessarily Syrian civil war, Aleppo, been the case.