DA Spring 03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuaderno De Documentacion

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA, MINISTERIO DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA DE ECONOMÍA SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ECONOMÍA INTERNACIONAL CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACION Número 43 Alvaro Espina Vocal Asesor 22 de Abril 2003 CUADERNO DE DOCUMENTACIÓN 22042003 43 Guerra de Irak: (VIII) 1.- Foreign Affairs May/June 2003, Vol 82, Number 3. Issue Highlight: “The Rise of Ethics in Foreign Policy: Reaching a Values Consensus” by Leslie H. Gelb and Justine A. Rosenthal "Why the Security Council Failed" by Michael Glennon “How to Build a Democratic Iraq” By Adeed Dawisha and Karen Dawisha “A Trusteeship for Palestine?” Martin Indyk “Is Turkey Ready for Europe?” by Michael S. Teitelbaum and Philip L. Martin ………………………………………………………………………………………Página 3 2.- Informe completo días 10, 11, 14, 16 y 17 de abril - April 17, 2003 MIDEAST ROADMAP: IRAQ WAR OPENS 'WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY' FOR PEACE .………………………………………….. Página 9 - April 16, 2003 IRAQ: THE HUNT FOR 'STUBBORNLY ELUSIVE' WMD…P. 27 - April 14, 2003 POST-IRAQ: SYRIA IS LIKELY 'NEXT VICTIM' OF U.S. 'IMPERIALISM' ……………………………………………………………Página 40 - April 10, 2003 DEATHS OF JOURNALISTS: SUSPICION U.S. ATTACKS WERE 'NO ACCIDENT' 1,? ……………………………………………...…... Página 61 - April 10, 2003 FALL OF BAGHDAD 'IMPRESSIVE' BUT 'TROUBLING' ………………………………………………………………………... Página 76 3.- Brookings Iraq Reports días 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 y 18 de abril ............................................................. ........................Página 99 1 TheNew National Security Strategy: Focus on Failed States by Susan E. Rice………………………………………………………… Página 111 4.- American Outlook Today, días 15, y 16 de abril …...................................................………… Página 117 5.- San Francisco Chronicle, The pictures of the war ……….................................................................. Página 123 “Plan for democracy in Iraq may be folly. Experts also question U.S. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

The Conflict in Iraq 23 MAY 2003

RESEARCH PAPER 03/50 The Conflict in Iraq 23 MAY 2003 Military operations to remove the Iraqi regime from power (Operation Iraqi Freedom) began officially at 0234 GMT on 20 March 2003. Coalition forces advanced rapidly into Iraq, encountering sporadic resistance from Iraqi military and paramilitary forces. By mid-April major combat operations had come to an end, with coalition forces in effective control of the whole country, including the capital Baghdad. This paper provides a summary of events in the build- up to the conflict, a general outline of the main developments during the military campaign between 20 March and mid April 2003 and an initial post-conflict assessment of the conduct of operations. Claire Taylor & Tim Youngs INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 03/35 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2003-04-11 10.04.03 03/36 Unemployment by Constituency, March 2003 17.04.03 03/37 Economic Indicators [includes article: The current WTO trade round] 01.05.03 03/38 NHS Foundation Trusts in the Health and Social Care 01.05.03 (Community Health and Standards) Bill [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/39 Social Care Aspects of the Health and Social Care (Community Health 02.05.03 and Standards Bill) [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/40 Social Indicators 06.05.03 03/41 The Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) 06.05.03 Bill: Health aspects other than NHS Foundation Trusts [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/42 The Fire Services Bill [Bill 81 of 2002-03] 07.05.03 -

ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY Regional Centres' Awards 2006/7

RTS Centre Awards 2004/5 ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY Regional Centres’ Awards 2006/7 West of England Craft Award for Camerawork/Lighting Camerawork Dec 2006 Chris Hutchins & Team BBC Features and Documentaries Single Item News Coverage The West Tonight: Pakistan ITV West Regional Television Personality of the Year Jed Pitman ITV West Regional TV – Reporter/Journalist of the Year John Maguire BBC Points West Regional Current Affairs Inside Out West – Crimea’s War BBC West Regional Documentary I Know What You Watched this Summer Swift Films for ITV West Regional Television News Programme The West Tonight ITV West Regional Independent Till the Boys Come Home – ‘A Brush with Death’ Wildfire Productions for ITV West Network Award - Specialist Factual Planet Earth from Pole to Pole BBC Natural History Unit Best Graphics and FX Direction Are we Changing Planet Earth?/Can we Save Planet Earth? BDH for BBC Specialist Factual, Science Network Award – Feature or Documentary Paul Merton’s Silent Clowns – Buster Keaton BBC Features & documentaries Network - Television Personality Noel Edmonds Endemol West Best Newcomer Alex Beresford ITV West Best International Co-production The Miracle of Stairway B Testimony Films for History Channel & Channel 4 - 1 - RTS Centre Awards 2004/5 Devon & Cornwall Network Documentary Nov 2006 Through Hell & High Water Twofour Broadcast for BBC TWO Non-Broadcast Headway Channel Television Network Leisure/Entertainment Cabin Fever Denham Productions for BBC TWO Network Series Hotel Inspector Series 2 Twofour Broadcast for -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

US Central Command for FY2005 – FY2007

Description of document: FOIA CASE LOGS for: United States Central Command, MacDill Air Force Base, FL for FY2005 – FY2007 Released date: 23-August-2007 Posted date: 07-December-2007 Title of Document 2005, 2006, 2007 Log Redacted Date/date range of document: 03-February-2004 – 29-June-2007 Source of document: United States Central Command CCJ6-RDF (FOIA) 7115 South Boundary Boulevard MacDill Air Force Base, Florida 33621-5101 Email: [email protected] Voice 813-827-1810 Fax 813-827-1241 Notes: Poor image quality in original file; therefore OCR accuracy limited. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file UNITED STATES CENTRAL COMMAND OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF 7115 SOUTH BOUNDARY BOULEVARD MACDI LL AIR FORCE BASE, FLORIDA 33621-510 I 23 August 2007 This is a final response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for an electronic copy of the FOIA Case Logs for U.S. Central Command for FY2005, FY2006 and FY2007 to date (2 July 2007). -

The War Correspondent

The War Correspondent The War Correspondent Fully updated second edition Greg McLaughlin First published 2002 Fully updated second edition first published 2016 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Greg McLaughlin 2002, 2016 The right of Greg McLaughlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3319 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3318 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1758 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1760 6 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1759 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the European Union and United States of America Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 PART I: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 2 The War Correspondent: Risk, Motivation and Tradition 9 3 Journalism, Objectivity and War 33 4 From Luckless Tribe to Wireless Tribe: The Impact of Media Technologies on War Reporting 63 PART II: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND THE MILITARY 5 Getting to Know Each Other: From Crimea to Vietnam 93 6 Learning and Forgetting: From the Falklands to the Gulf 118 7 Goodbye Vietnam Syndrome: The Embed System in Afghanistan and Iraq 141 PART III: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND IDEOLOGICAL FRAMEWORKS 8 Reporting the Cold War and the New World Order 161 9 Reporting the ‘War on Terror’ and the Return of the Evil Empire 190 10 Conclusions: ‘Telling Truth To Power’ – the Ultimate Role of the War Correspondent? 214 1 Introduction William Howard Russell is widely regarded as one of the first war cor- respondents to write for a commercial daily newspaper. -

AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017

Pulitzer Center Pulitzer Center Gender Lens Conference Gender Lens Conference June 3 – 4, 2017 AGENDA June 3 – 4, 2017 Saturday, June 3, 2017 2:00-2:30 Registration 2:30-3:45 Concurrent panels 1) Women in Conflict Zones Welcome: Tom Hundley, Pulitzer Center Senior Editor • Susan Glasser, Politico chief international affairs columnist and host of The Global Politico (moderator) • Paula Bronstein, freelance photojournalist (G) • Sarah Holewinski, senior fellow, Center for a New American Security, board member, Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) • Sarah Topol, freelance journalist (G) • Cassandra Vinograd, freelance journalist (G) 2) Property Rights Welcome: Steve Sapienza, Pulitzer Center Senior Producer • LaShawn Jefferson, deputy director, Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania (moderator) • Amy Toensing, freelance photojournalist (G) • Paola Totaro, editor, Thomson Reuters Foundation’s Place • Nana Ama Yirrah, founder, COLENDEF 3) Global Health • Rebecca Kaplan, Mellon/ACLS Public Fellow at the Pulitzer Center (moderator) • Jennifer Beard, Clinical Associate Professor, Boston University School of Public Health (Pulitzer Center Campus Consortium partner) • Caroline Kouassiaman, senior program officer, Sexual Health and Rights, American Jewish World Service (AJWS) • Allison Shelley, freelance photojournalist (G) • Rob Tinworth, filmmaker (G) 4:00-4:30 Coffee break 4:30-5:45 Concurrent panels 1) Diversifying the Story • Yochi Dreazen, foreign editor of Vox.com (moderator) (G) • Kwame Dawes, poet, writer, actor, musician, professor -

'Embedded' with the Invaded Iraqi People

THE INDIGENOUS PUBLIC SPHERE DR DAVID ROBIE is an associate professor in Auckland University of Technology’s School of Communication Studies. ‘Embedded’ with the invaded Iraqi people Long Drive Through a Short War: Reporting on the Iraq War, by Peter Wilson, 2004. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books. 294 pp. ISBN 1 74066 143 5. Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib, by Seymour M. land’s handful of television reporters Hersh, 2004. London: Allen Lane (Pen- covered the war from the safety of the guin). 394 pp. ISBN 0 7139 9849 0. rear or were embedded. According to the Paris-based glo- bal media watchdog, Reporters Sans EW journalists from this part of Frontières, Coalition forces displayed Fthe world chose to report the 2003 ‘contempt’ for unilaterals. Many jour- invasion of Iraq as ‘unilaterals’ – nalists came under fire, others were those who reported from outside the detained and questioned for several cosy security of the ‘embedded’ re- hours or days and some were mis- porters were attached to the Coalition treated, beaten and humiliated by military. Only one unilateral was from Coalition forces. New Zealand: Jon Stephenson, who Of the 14 journalists who died provided at great personal risk some while the embedded system was in invaluable independent insights for full force – from the start of the war the Sunday Star-Times. New Zea- on March 20 until the fall of 220 PACIFIC JOURNALISM REVIEW 11 (1) 2005 THE INDIGENOUS PUBLIC SPHERE Saddam’s statue on April 9 – only four to him being named the 2003 Aus- of the casualties were embedded, tralian Journalist of the Year and his even though the 700 or so embeds experiences and independent view greatly outnumbered their unilateral provide plenty of depth for this book. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1998 - June 30,1999 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-•1789 TTele . (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail communications@cfr. org Officers and Directors, 1999–2000 Officers Directors Term Expiring 2004 Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 2000 John Deutch Chairman of the Board Jessica P.Einhorn Carla A. Hills Maurice R. Greenberg Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Robert D. Hormats* Vice Chairman Maurice R. Greenberg William J. McDonough* Leslie H. Gelb Theodore C. Sorensen President George J. Mitchell George Soros* Michael P.Peters Warren B. Rudman Senior Vice President, Chief Operating Term Expiring 2001 Leslie H. Gelb Officer, and National Director ex officio Lee Cullum Paula J. Dobriansky Vice President, Washington Program Mario L. Baeza Honorary Officers David Kellogg Thomas R. Donahue and Directors Emeriti Vice President, Corporate Affairs, Richard C. Holbrooke Douglas Dillon and Publisher Peter G. Peterson† Caryl P.Haskins Lawrence J. Korb Robert B. Zoellick Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Vice President, Studies David Rockefeller Term Expiring 2002 Elise Carlson Lewis Honorary Chairman Vice President, Membership Paul A. Allaire and Fellowship Affairs Robert A. Scalapino Roone Arledge Abraham F. Lowenthal Cyrus R.Vance John E. Bryson Vice President Glenn E. Watts Kenneth W. Dam Anne R. Luzzatto Vice President, Meetings Frank Savage Janice L. Murray Laura D’Andrea Tyson Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2003 Judith Gustafson Secretary Peggy Dulany Martin S. -

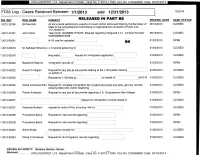

Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 RELEASED IN

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2013-17945 Doc No. C05494608 Date: 04/16/2014 FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 1/2/2014 tEQ REF REQ_NAME SUBJECT RELEASED IN PART B6 RECEIVE DATE CASE STATUS 2012-26796 Bill Marczak All documents pertaining to exports of crowd control items submitted by the Secretary of 08/14/2013 CLOSED State to the Congressional Committees on Appropriations pursuant to Public Law 112-74042512 2012-31657 John Calvit Task Order: SAQMMA11F0233. Request regarding Vanguard 2.2.1. Contract Number: 08/14/2013 CLOSED GS00Q09BGF0048 L-2013-00001 H-1B visa for requester B6 01/02/2013 OPEN 2013-00078 M. Kathleen Minervino J-1 records pertaining to 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00218 Requestor request for immigration application 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00220 Bashist M Sharma immigration records of 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00222 Robert D Ahlgren Request for any and all documents relating to the 1-130 petition filed by 01/02/2013 CLOSED on behalf of F-2013-00223 Request for 1-130 filed 1.)- on behalf of NVC # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00224 Gloria Contreras Edin Request for complete immigration file including all entries and exits, and any records 01/02/2013 CLOSED showing false USC claims regarding F-2013-00226 Parker Anderson Request for any and all documents regarding U.S. Congressman Sam Steiger. 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00227 request for immigration records receipt # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00237 Kayleyne Brottem request for entire A-File, including 1-94 for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00238 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00239 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00242 Sonia Alcala Immigration records for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00243 Gloria C Cardenas Request for all immigration records regarding 01/02/2013 CLOSED REVIEW AUTHORITY: Barbara Nielsen, Senior Reviewer UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

Media Coverage of the 2003 Iraq War

Lewis, J., Brookes, R., Mosdell, N. and Threadgold, T. (2006) Shoot First and Ask Questions Later: Media Coverage of the 2003 Iraq War. Peter Lang, New York (p.94–100) Many of our open‐ended questions directed at editors and journalists were intended to elicit their views about the policy of embedded reporting as a central component of U.S./UK military news management strategy. Much of the criticism levelled at embedding has been aimed at the dependence of correspondents‐on their units for food and water, transport and safety, suggesting that this close and dependent relationship compromises the ability of correspondents to be critical of military personnel. All of our respondents expressed an awareness of this issue. Many of the correspondents said that they could not help developing friendships with military personnel as a result of their common situation. Indeed, developing friendly relations with the troops was important for correspondents in helping them to do their job. Phil Wardman recalled how Jeremy Thompson made himself popular with the troops by down‐linking Sky Sports for them. According to Wardman, Sky deliberately assigned reporters to units who would be likely to get along with the troops. At the same time, correspondents who discussed the issue denied ythat an friendships formed with the soldiers influenced how they reported the war. A number of examples illustrate the potential for the position of the embedded journalist to be compromised. A number of journalists reported occasions where they were uncomfortably close to the soldiers they accompanied. Ben Brown recalled how a soldier had saved his life by shooting an Iraqi sniper: There was an Iraqi who had been playing dead the other side of a wall very close to us, and he had been pretending to be dead.