Media Coverage of the 2003 Iraq War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

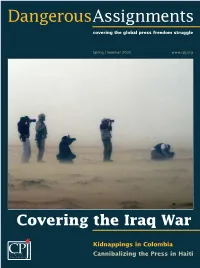

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

The Conflict in Iraq 23 MAY 2003

RESEARCH PAPER 03/50 The Conflict in Iraq 23 MAY 2003 Military operations to remove the Iraqi regime from power (Operation Iraqi Freedom) began officially at 0234 GMT on 20 March 2003. Coalition forces advanced rapidly into Iraq, encountering sporadic resistance from Iraqi military and paramilitary forces. By mid-April major combat operations had come to an end, with coalition forces in effective control of the whole country, including the capital Baghdad. This paper provides a summary of events in the build- up to the conflict, a general outline of the main developments during the military campaign between 20 March and mid April 2003 and an initial post-conflict assessment of the conduct of operations. Claire Taylor & Tim Youngs INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 03/35 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2003-04-11 10.04.03 03/36 Unemployment by Constituency, March 2003 17.04.03 03/37 Economic Indicators [includes article: The current WTO trade round] 01.05.03 03/38 NHS Foundation Trusts in the Health and Social Care 01.05.03 (Community Health and Standards) Bill [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/39 Social Care Aspects of the Health and Social Care (Community Health 02.05.03 and Standards Bill) [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/40 Social Indicators 06.05.03 03/41 The Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) 06.05.03 Bill: Health aspects other than NHS Foundation Trusts [Bill 70 of 2002-03] 03/42 The Fire Services Bill [Bill 81 of 2002-03] 07.05.03 -

ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY Regional Centres' Awards 2006/7

RTS Centre Awards 2004/5 ROYAL TELEVISION SOCIETY Regional Centres’ Awards 2006/7 West of England Craft Award for Camerawork/Lighting Camerawork Dec 2006 Chris Hutchins & Team BBC Features and Documentaries Single Item News Coverage The West Tonight: Pakistan ITV West Regional Television Personality of the Year Jed Pitman ITV West Regional TV – Reporter/Journalist of the Year John Maguire BBC Points West Regional Current Affairs Inside Out West – Crimea’s War BBC West Regional Documentary I Know What You Watched this Summer Swift Films for ITV West Regional Television News Programme The West Tonight ITV West Regional Independent Till the Boys Come Home – ‘A Brush with Death’ Wildfire Productions for ITV West Network Award - Specialist Factual Planet Earth from Pole to Pole BBC Natural History Unit Best Graphics and FX Direction Are we Changing Planet Earth?/Can we Save Planet Earth? BDH for BBC Specialist Factual, Science Network Award – Feature or Documentary Paul Merton’s Silent Clowns – Buster Keaton BBC Features & documentaries Network - Television Personality Noel Edmonds Endemol West Best Newcomer Alex Beresford ITV West Best International Co-production The Miracle of Stairway B Testimony Films for History Channel & Channel 4 - 1 - RTS Centre Awards 2004/5 Devon & Cornwall Network Documentary Nov 2006 Through Hell & High Water Twofour Broadcast for BBC TWO Non-Broadcast Headway Channel Television Network Leisure/Entertainment Cabin Fever Denham Productions for BBC TWO Network Series Hotel Inspector Series 2 Twofour Broadcast for -

US Central Command for FY2005 – FY2007

Description of document: FOIA CASE LOGS for: United States Central Command, MacDill Air Force Base, FL for FY2005 – FY2007 Released date: 23-August-2007 Posted date: 07-December-2007 Title of Document 2005, 2006, 2007 Log Redacted Date/date range of document: 03-February-2004 – 29-June-2007 Source of document: United States Central Command CCJ6-RDF (FOIA) 7115 South Boundary Boulevard MacDill Air Force Base, Florida 33621-5101 Email: [email protected] Voice 813-827-1810 Fax 813-827-1241 Notes: Poor image quality in original file; therefore OCR accuracy limited. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file UNITED STATES CENTRAL COMMAND OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF 7115 SOUTH BOUNDARY BOULEVARD MACDI LL AIR FORCE BASE, FLORIDA 33621-510 I 23 August 2007 This is a final response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for an electronic copy of the FOIA Case Logs for U.S. Central Command for FY2005, FY2006 and FY2007 to date (2 July 2007). -

'Embedded' with the Invaded Iraqi People

THE INDIGENOUS PUBLIC SPHERE DR DAVID ROBIE is an associate professor in Auckland University of Technology’s School of Communication Studies. ‘Embedded’ with the invaded Iraqi people Long Drive Through a Short War: Reporting on the Iraq War, by Peter Wilson, 2004. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books. 294 pp. ISBN 1 74066 143 5. Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib, by Seymour M. land’s handful of television reporters Hersh, 2004. London: Allen Lane (Pen- covered the war from the safety of the guin). 394 pp. ISBN 0 7139 9849 0. rear or were embedded. According to the Paris-based glo- bal media watchdog, Reporters Sans EW journalists from this part of Frontières, Coalition forces displayed Fthe world chose to report the 2003 ‘contempt’ for unilaterals. Many jour- invasion of Iraq as ‘unilaterals’ – nalists came under fire, others were those who reported from outside the detained and questioned for several cosy security of the ‘embedded’ re- hours or days and some were mis- porters were attached to the Coalition treated, beaten and humiliated by military. Only one unilateral was from Coalition forces. New Zealand: Jon Stephenson, who Of the 14 journalists who died provided at great personal risk some while the embedded system was in invaluable independent insights for full force – from the start of the war the Sunday Star-Times. New Zea- on March 20 until the fall of 220 PACIFIC JOURNALISM REVIEW 11 (1) 2005 THE INDIGENOUS PUBLIC SPHERE Saddam’s statue on April 9 – only four to him being named the 2003 Aus- of the casualties were embedded, tralian Journalist of the Year and his even though the 700 or so embeds experiences and independent view greatly outnumbered their unilateral provide plenty of depth for this book. -

Slaughter in Iraq

Slaughter in Iraq 20 March 2003 – 20 March 2006 A total of 86 journalists and media assistants have been killed and 38 have been kidnapped during three years of war - Who were they? - Which media did they work for? - In what circumstances were they killed or kidnapped? - By whom? March 2006 Reporters Without Borders 5, rue Geoffroy-Marie – 75009 Paris (France) Tel: (33) 1 4483-8484 Fax: (33) 1 4523-1151 [email protected] www.rsf.org The war in Iraq has proved to be the deadliest for journalists since World War II. A total of 86 journalists and media assistants1 have been killed in Iraq since the war began on 20 March 2003. This is more than the number killed during 20 years of war in Vietnam or the civil war in Algeria. Iraq is also one of the world’s biggest marketplaces for hostages, with 38 journalists kidnapped in three years. Five of them were executed. Three - Jill Carroll, Reem Zeid and Marwan Khazaal – are still being held by their abductors. Around 63 journalists were killed in Vietnam during the 20 years from 1955 to 19752. A total of 49 media professionals were killed in the course of their work during the war in ex- Yugoslavia, from 1991 to1995. During the civil war in Algeria from 1993 to 1996, 77 journalists and media assistants were killed. Paul Moran, an Australian cameraman working for ABC television, was the first of the long series of journalists to die in Iraq. He was killed by a car bomb right at the start of the war, on 22 March 2003. -

Lettre Famille Congrès.Indd

Dear Congressional Members, We are the families of journalists killed or missing in Iraq during the year 2003. We are writing to you jointly from Amman, Ramallah, London, Brussels, Warsaw and the Bekaa Valley (Lebanon), backed by Reporters Without Borders, to express our deep dismay and grief at the silence, lack of information and the untruth emanating from your government about the fate of our loved ones. Tarek, Mazen, Terry, Fred, Hussein and Taras were journalists. They acquired the experience and wisdom of war reporters by covering the Balkans, Afghanistan, Chechnya and the Israeli-Palestinian confl ict. Just a year ago, they were sent to Iraq to report on the confl ict and upheaval in the region. As seasoned war correspon- April 8 2004 dents, they were well prepared in advance of what they were to expect when they arrived in Iraq. This war was to be their last. On 22 March 2003, a team from the British TV network ITN led by star reporter Terry Lloyd came under US and Iraqi gunfi re near Basra, in southern Iraq. Terry was most probably killed by US Marines. French came- raman Fred Nérac and Lebanese interpreter Hussein Osman mysteriously vanished. The British military police started an investigation in June but was never allowed to question the Marines involved. Despite the promises of Secretary of State Colin Powell, the US Army has not cooperated suffi ciently with British investigators and so reduced the chances of fi nding out what really happened including recove- ring the bodies of Fred and Hussein. April 8 was a terrible day for the media in Baghdad. -

The Hollywoodization Of

1 The Hollywoodisation of war: The media handling of the Iraq war Alan Knight Is this war going to make history by being the first to end before its cause is found? Geoff Meade, SKY TV (Meade 2003) The media war over Iraq began with an ominous warning. US President, George W. Bush told journalists to leave Baghdad, because he could not guarantee their safety. 1 Events in Iraq had reached the “final days of decision”, he said. Saddam Hussein and his sons, like a gang of Hollywood rustlers, were given forty eight hours to get out of town. Three days later the invasion of Iraq began. This article considers the propaganda techniques deployed by both sides in the 2003 Iraq war as they sought to manipulate global coverage of events. It draws extensively on internet sources, in part because the fragmented reports from the field became in the end less important than the globalised whole which consisted of text, audio and television converging on the world wide web. 2 Truth? The first point of the code of conduct for International Federation of Journalists states “Respect for truth and for the right of the public to truth is the first duty of the journalist.” (IFJ Conduct of Journalists) Yet truth does not always have quick victories in modern warfare where the battle for global opinion may be as intense as the contest of military technology. Free speech comes at a cost. The Committee to Protect Journalists reported as Baghdad fell, that nine journalists had been killed during the Iraq invasion. -

This Book Is Available from the British Library

The War Correspondent The War Correspondent Fully updated second edition Greg McLaughlin First published 2002 Fully updated second edition first published 2016 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Greg McLaughlin 2002, 2016 The right of Greg McLaughlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3319 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3318 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1758 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1760 6 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1759 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the European Union and United States of America To Sue with love Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations x 1 Introduction 1 PART I: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 2 The War Correspondent: Risk, Motivation and Tradition 9 3 Journalism, Objectivity and War 33 4 From Luckless Tribe to Wireless Tribe: The Impact of Media Technologies on War Reporting 63 PART II: THE WAR CORRESPONDENT AND THE MILITARY 5 Getting to Know Each Other: From Crimea to Vietnam 93 6 Learning and Forgetting: From the Falklands to the -

The Iran-Iraq War: an Interview with Mohamad Ali Torabi

Barnard-1 The Iran-Iraq War: An interview with Mohamad Ali Torabi Interviewer: Amelia Barnard Instructor: Amanda Freeman February 12, 2018 Barnard-2 Table of Contents Interviewer release form …. Pg 3 Interviewee release form ….. Pg 4 Statement of purpose …. Pg 5 Biography …. Pg 6 Historical Contextualization Paper …. Pg 7 Interview Transcription …. Pg 15 Interview Analysis …. Pg 45 Biography …. Pg 46 Barnard-3 Release form Barnard-4 Release form Barnard-5 Statement of purpose The purpose of this oral history with Mamali Torabi is to collect and preserve a primary source account of The Iran-Iraq war. By reading the contents of this project that converges evidence from multiple sources, one will gain background information about The Iran Iraq War as well as the perspective of someone who was directly impacted by the war. Barnard-6 Biography Mamali Torabi grew up in Tehran, Iran in a large family with six younger siblings, two of which did not make pass the age of 2. He graduated from Dr. Hashtroody High School of Mathematics in Tehran in 1979 as the first graduating class under the new Regime of The Islamic Republic of Iran. After passing his Exit exam, he moved to Stockholm, Sweden as a foreign student. In 1981 he finally got his Visa to the United States after the hostage crisis was cleared up and he started in George Washington University to study English. In January of 1982 he enrolled in Sacramento City College because his uncle who lived there got sick. In the Winter of 1982 he came back to the Washington area and started a career in Sales and Management in Home Furnishing for 17 years. -

Journalists Under Fire 00-Tumber-Prelims.Qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page Ii 00-Tumber-Prelims.Qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page Iii

00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page i Journalists Under Fire 00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page ii 00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page iii Journalists Under Fire Information War and Journalistic Practices Howard Tumber and Frank Webster SAGE Publications London ●●Thousand Oaks New Delhi 00-Tumber-Prelims.qxd 3/14/2006 2:59 PM Page iv © Howard Tumber and Frank Webster 2006 First published 2006 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP SAGE Publications Inc. 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B-42, Panchsheel Enclave Post Box 4109 New Delhi 110 017 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN-10 1-4129-2406-5 ISBN-13 978-1-4129-2406-1 ISBN-10 1-4129-2407-3 (pbk) ISBN-13 978-1-4129-2407-8 Library of Congress Control Number available Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed in Great Britain by Athenaeum Press, Gateshead Printed on -

The Derby Guardian

1 THE DERBY GUARDIAN An independent community paper, by email, for the people of Derby Volume 1 No. 12 January 22, 2004 News of entertainments and the arts in the city includes an anniversary to be observed worldwide. Holocaust Memorial Day is on Tuesday, January 27, and among the events during the week in Derby will be the Metro Cinema screening on Monday evening of All Quiet on the Western Front, the classic anti-war film. The film was based on the book by Eric Maria Remarque, a native of Osnabruck – now Derby’s twin city in Germany. At the Assembly Rooms on Wednesday, February 4, the famous former steeplejack and now travelling raconteur, Fred Dibnah, is expected to attract a full house. Box office D.255800. Our entertainments lists appear in the Derby Flyer each week. And see below: An honorary degree from Derby University is to be presented to the family of Terry Lloyd, the Derby-born journalist who was killed during the war in Iraq. The father of the city council, former Mayor Ray Baxter, is in the DRI after a collision with a car while walking with his wife, Jose, near their home in Mackworth. © Brennan Publications weekly on subscription [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Budding film-makers can challenge the world Metro raises profile of local talent A creative teacher in a certain college in the region has started a series of freewheeling but challenging course discussions with the title Creative Connections (writes our film editor). As a simple introduction he asked them to make connections between the ideas and the processes which led many years ago to the production in Derby of the world- renowned Rolls-Royce cars, and a small local company now, which has secured an American contract for a new software programme.