Women War Reporters' Resistance and Silence In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Face the Nation

© 2006 CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION. " CBS News FACE THE NATION Sunday, June 11, 2006 GUESTS: General GEORGE CASEY Commander, Multi-National Force, Iraq THOMAS FRIEDMAN Columnist, The New York Times LARA LOGAN CBS News Chief Foreign Correspondent ELIZABETH PALMER CBS News Correspondent MODERATOR: BOB SCHIEFFER - CBS News This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS 202-457-4481 BURRELLE'S INFORMATION SERVICES / 202-419-1859 / 800-456-2877 Face the Nation (CBS News) - Sunday, June 11, 2006 1 BOB SCHIEFFER, host: Today on FACE THE NATION, after Zarqawi. Is the death of the terrorist in Iraq a turning point? It took two 500-pound bombs, but US forces finally got him. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq. How will his death affect the war? We'll talk with Lara Logan, our chief foreign correspondent, and CBS News correspondent Elizabeth Palmer, who is in Baghdad. Then we'll talk to our top general in Iraq, General George Casey, on where we go from here. We'll get analysis and perspective on all this from New York Times columnist Tom Friedman. And I'll have a final word on congressional ethics. Is that an oxymoron? But first, the death of Zarqawi on FACE THE NATION. Announcer: FACE THE NATION, with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF JOURNALISM STORIES FROM THE FRONT LINES: FEMALE FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS IN WAR ZONES JENNIFER CONNOR SUMMER 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Journalism with honors in Journalism. Reviewed and approved* by the following: Tony Barbieri Foster Professor of Writing and Editing Thesis Supervisor Martin Halstuk Associate Professor Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to examine the experience of women who cover war and conflict zones, with a special focus on those reporting in Iraq and Afghanistan. When western female war correspondents work in male-dominated cultures and situations of war, they encounter different challenges and advantages than male war correspondents. The level of danger associated with the assignments these women take on is evaluated in this thesis. Anecdotes from female war correspondents themselves, combined with outside analysis, reveal the types of situations unique to female war correspondents. More women choose to follow the story and witness history in the making by covering today‟s war and conflict zones. This trend parallels the greater presence of women in newsrooms, today. This thesis will shed light on what it means to be a female reporting on and working in dangerous conditions. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………....1 Part 2. Dealing with Danger……………………………………………………………………...6 -

Download The

Nothing to declare: Why U.S. border agency’s vast stop and search powers undermine press freedom A special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists Nothing to declare: Why U.S. border agency’s vast stop and search powers undermine press freedom A special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists Founded in 1981, the Committee to Protect Journalists responds to attacks on the press worldwide. CPJ documents hundreds of cases every year and takes action on behalf of journalists and news organizations without regard to political ideology. To maintain its independence, CPJ accepts no government funding. CPJ is funded entirely by private contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations. CHAIR HONORARY CHAIRMAN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Kathleen Carroll Terry Anderson Joel Simon DIRECTORS Mhamed Krichen Ahmed Rashid al-jazeera Stephen J. Adler David Remnick reuters Isaac Lee the new yorker Franz Allina Lara Logan Alan Rusbridger Amanda Bennett cbs news lady margaret hall, oxford Krishna Bharat Rebecca MacKinnon David Schlesinger Susan Chira Kati Marton Karen Amanda Toulon bloomberg news the new york times Michael Massing Darren Walker Anne Garrels Geraldine Fabrikant Metz ford foundation the new york times Cheryl Gould Jacob Weisberg Victor Navasky the slate group Jonathan Klein the nation getty images Jon Williams Clarence Page rté Jane Kramer chicago tribune the new yorker SENIOR ADVISORS Steven L. Isenberg Sandra Mims Rowe Andrew Alexander David Marash Paul E. Steiger propublica Christiane Amanpour Charles L. Overby cnn international freedom forum Brian Williams msnbc Tom Brokaw Norman Pearlstine nbc news Matthew Winkler Sheila Coronel Dan Rather bloomberg news columbia university axs tv school of journalism Gene Roberts James C. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL NOTICE GIVEN NO EARLIER THAN 7:00 PM EDT ON SATURDAY 9 JULY 2016 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CATHLEEN COLVIN, individually and as Civil No. __________________ parent and next friend of minors C.A.C. and L.A.C., heirs-at-law and beneficiaries Complaint For of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, heir-at-law and 28 U.S.C. § 1605A beneficiary of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, c/o Center for Justice & Accountability, One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 406, San Francisco, CA 94102 Plaintiffs, v. SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC, c/o Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem Ministry of Foreign Affairs Kafar Soussa, Damascus, Syria Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Cathleen Colvin and Justine Araya-Colvin allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. On February 22, 2012, Marie Colvin, an American reporter hailed by many of her peers as the greatest war correspondent of her generation, was assassinated by Syrian government agents as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria—a city beseiged by Syrian military forces. Acting in concert and with premeditation, Syrian officials deliberately killed Marie Colvin by launching a targeted rocket attack against a makeshift broadcast studio in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs where Colvin and other civilian journalists were residing and reporting on the siege. 2. The rocket attack was the object of a conspiracy formed by senior members of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (the “Assad regime”) to surveil, target, and ultimately kill civilian journalists in order to silence local and international media as part of its effort to crush political opposition. -

It's What I Do Lynsey Addario

Datasheet of the exhibition It’s What I Do Lynsey Addario Associazione Culturale ONTHEMOVE DATASHEET OF EXHIBITION | Lynsey Addario - It’s What I Do 1 It’s What I Do Curater by Lynsey Addario Arianna Rinaldo Produced by Prints Associazione Culturale ONTHEMOVE Bottega Antonio Manta on the occasion of Cortona On The Move SP Systema International Photography Festival 2016 Frames Studio Rufus Associazione Culturale ONTHEMOVE | Località Vallone, 39/A/4 - Cortona, 52044 (AR) DATASHEET OF EXHIBITION | Lynsey Addario - It’s What I Do 2 It’s What I Do When I began contemplating the idea of showing Lynsey’s work in Cortona, I had never met her personally. Nonetheless she felt like someone close. Someone I could very easily be friends with and have a glass of wine talking about the last movie we saw. I had seen a few videos and interviews online featuring her relentless spirit, her uplifting attitude and restless photojournalistic mission. When I read her book, “It’s What I Do”, I felt even more interested in her work and her persona. She was a champion of focus, commitment and bravery paired with positive attitude and a very human heart. We also had some things in common. She is a freelance working mom, like me, more or less my age. We share friends on Facebook, and often read and “like” the same articles on photography and news. However, Lynsey, for me, is a heroine. She travels the world non-stop to be a witness to social injustice, war and humanitarian tragedies and many other neglected issues, giving voice to people and light to places, that are left in the shadow when the media frenzy fades. -

Photojournalism

ASSOCIATION VISA POUR L’IMAGE - PERPIGNAN Couvent des Minimes, 24, rue Rabelais - 66000 Perpignan tel: +33 (0)4 68 62 38 00 e-mail: [email protected] - www.visapourlimage.com FB Visa pour l’Image - Perpignan @visapourlimage PRESIDENT RENAUD DONNEDIEU DE VABRES rd VICE-PRESIDENT/TREASURER PIERRE BRANLE AUGUST 28 TO SEPTEMBER 26, 2021 COORDINATION ARNAUD FELICI & JÉRÉMY TABARDIN ASSISTANTS (COORDINATION) CHRISTOPHER NOU & NATHAN NOELL PRESS/PUBLIC RELATIONS 2e BUREAU 18, rue Portefoin - 75003 Paris INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF tel: +33 (0)1 42 33 93 18 e-mail: [email protected] 33 www.2e-bureau.com Instagram & Twitter@2ebureau DIRECTOR GENERAL, COORDINATION SYLVIE GRUMBACH MANAGEMENT/ACCREDITATIONS VALÉRIE BOURGOIS PRESS RELATIONS MARTIAL HOBENICHE, DANIELA JACQUET ANNA ROUFFIA PHOTOJOURNALISM FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT Program subject to change due to Covid-19 health restrictions IMAGES EVIDENCE 4, rue Chapon - Bâtiment B - 75003 Paris tel: +33 (0)1 44 78 66 80 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FB Jean Francois Leroy Twitter @jf_leroy Instagram @visapourlimage DIRECTOR GENERAL JEAN-FRANÇOIS LEROY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DELPHINE LELU COORDINATION CHRISTINE TERNEAU ASSISTANTJEANNE RIVAL SENIOR ADVISOR JEAN LELIÈVRE SENIOR ADVISOR – USA ELIANE LAFFONT SUPERINTENDENCE ALAIN TOURNAILLE TEXTS FOR SCREENINGS, PRESENTATIONS & RECORDED VOICE - FRENCH PAULINE CAZAUBON “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR CAROLINE LAURENT-SIMON BLOG & “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” CO-MODERATOR VINCENT JOLLY PROOFREADING OF FRENCH TEXTS & -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

A Film by BORIS LOJKINE NINA MEURISSE

UNITÉ DE PRODUCTION PRESENTS Piazza Grande NINA MEURISSE a film by BORIS LOJKINE with FIACRE BINDALA BRUNO TODESCHINI GRÉGOIRE COLIN Unité de Production presents NINA MEURISSE a film by BORIS LOJKINE with VENTES INTERNATIONALES FIACRE BINDALA BRUNO TODESCHINI GRÉGOIRE COLIN Pyramide International (+33) 1 42 96 02 20 [email protected] / [email protected] DISTRIBUTION FRANCE Pyramide Distribution Running time : 90 MN 01 42 96 01 01 32 rue de l’Echiquier, 75010 Paris RELATIONS PRESSE FRANCE Hassan Guerrar / Julie Braun 01 40 34 22 95 [email protected] Photos and Press Kit downloadable on www.pyramidefilms.com SYNOPSIS Camille, a young idealistic photojournalist, goes to the Central African Republic to cover the civil war that is brewing up. What she sees there will change her destiny forever. Jeune photojournaliste éprise d'idéal, Camille part en Centrafrique couvrir la guerre civile qui se prépare. Ce qu’elle voit là-bas changera son destin. the following days… but they could not stop the spiral international community was focusing on other of violence. Because while the French disarmed and conflicts, Camille searched a way to dig deeper. She confined the Séléka to their barracks, the Christian notably tried to establish contacts with the Anti- community, hungry for revenge, turned against the balaka, in the hope of telling their story from within. by Boris Lojkine ABOUT THE FEATURE Muslim community. In May, as she was travelling in the western part of the country, she met a young Anti-balaka chief, Rocka Camille Lepage photographed it all. Mokom, who agreed to let her come along while he The burst of violence, the tragedy, the madness, the patrolled the CAR border with Cameroon, in an area A PROPOS DU FILM killing frenzy, death. -

![By Miriam Aronin [Intentionally Left Blank] JANUARY 12, 2010](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5664/by-miriam-aronin-intentionally-left-blank-january-12-2010-625664.webp)

By Miriam Aronin [Intentionally Left Blank] JANUARY 12, 2010

JANUARY 12, 2010 by Miriam Aronin [Intentionally Left Blank] JANUARY 12, 2010 by Miriam Aronin Consultant: Robert Maguire Associate Professor of International Affairs and Director of the Haiti Program Trinity Washington University, Washington, D.C. Credits Cover and Title Page, © Mark Pearson/Alamy; TOC, © Winnipeg Free Press, Thursday, January 14, 2010/ Newspaper Archive; 4, © AP Images/Ramon Espinosa; 5, © Damon Winter/The New York Times/Redux; 6, © James Breeden/Pacific Coast News/Newscom; 7, © Rick Loomis/Los Angeles Times/MCT/Newscom; 8, © Patrick Farrell/Miami Herald/MCT/Newscom; 9, © AP Images/Rodrigo Abd; 10, © Jean-Paul Pelissier/ Reuters/Landov; 11, © Marco Dormino/UN/Minustah/Reuters/Landov; 12, © Lynsey Addario/New York Times/VII Photo Agency LLC; 13T, © U.S. Navy/Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Justin Stumberg; 13B, © U.S. Navy/Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Daniel Barker; 14, © AP Images/ Bebeto Matthews; 15, © Matthew Bigg/Reuters/Landov; 16L, © Pedro Portal/El Nuevo Herald/MCT/ Newscom; 16R, © Olivier Laban-Mattei/AFP/Newscom; 17, © AP Images/Ramon Espinosa; 18, © Talia Frenkel/American Red Cross; 19, © AP Images/Mark Davis/Hope for Haiti Now; 20, © AP Images/J. Pat Carter; 21, © AP Images/Ariana Cubillos; 22T, © Lui Kit Wong/The News Tribune; 22B, Courtesy of Pamela Bridge; 23T, Courtesy of the British Red Cross; 23B, Special thanks to Ashley Johnson, The Empowerment Academy #262, Baltimore Maryland; 24, © U.S. Navy/Logistics Specialist 1st Class Kelly Chastain; 25, © Pasqual Gorriz/United Nations Photos/AFP/Newscom; 26T, © Hans Deryk/Reuters/Landov; 26BL, © Hazel Trice Edney/NPPA; 26BR, © Lexey Swall/Naples Daily News; 27, © Michael Laughlin/Sun Sentinel/MCT/ Newscom; 28T, © AP Images/Ramon Espinosa; 28B, © AP Images/J. -

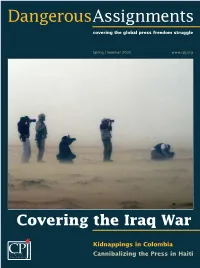

DA Spring 03

DangerousAssignments covering the global press freedom struggle Spring | Summer 2003 www.cpj.org Covering the Iraq War Kidnappings in Colombia Committee to·Protect Cannibalizing the Press in Haiti Journalists CONTENTS Dangerous Assignments Spring|Summer 2003 Committee to Protect Journalists FROM THE EDITOR By Susan Ellingwood Executive Director: Ann Cooper History in the making. 2 Deputy Director: Joel Simon IN FOCUS By Amanda Watson-Boles Dangerous Assignments Cameraman Nazih Darwazeh was busy filming in the West Bank. Editor: Susan Ellingwood Minutes later, he was dead. What happened? . 3 Deputy Editor: Amanda Watson-Boles Designer: Virginia Anstett AS IT HAPPENED By Amanda Watson-Boles Printer: Photo Arts Limited A prescient Chinese free-lancer disappears • Bolivian journalists are Committee to Protect Journalists attacked during riots • CPJ appeals to Rumsfeld • Serbia hamstrings Board of Directors the media after a national tragedy. 4 Honorary Co-Chairmen: CPJ REMEMBERS Walter Cronkite Our fallen colleagues in Iraq. 6 Terry Anderson Chairman: David Laventhol COVERING THE IRAQ WAR 8 Franz Allina, Peter Arnett, Tom Why I’m Still Alive By Rob Collier Brokaw, Geraldine Fabrikant, Josh A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recounts his days and nights Friedman, Anne Garrels, James C. covering the war in Baghdad. Goodale, Cheryl Gould, Karen Elliott House, Charlayne Hunter- Was I Manipulated? By Alex Quade Gault, Alberto Ibargüen, Gwen Ifill, Walter Isaacson, Steven L. Isenberg, An embedded CNN reporter reveals who pulled the strings behind Jane Kramer, Anthony Lewis, her camera. David Marash, Kati Marton, Michael Massing, Victor Navasky, Frank del Why I Wasn’t Embedded By Mike Kirsch Olmo, Burl Osborne, Charles A CBS correspondent explains why he chose to go it alone. -

The Looming Crisis: Displacement and Security in Iraq

Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS POLICY PAPER Number 5, August 2008 The Looming Crisis: Displacement and Security in Iraq Elizabeth G. Ferris The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20036 brookings.edu Foreign Policy at BROOKINGS POLICY PAPER Number 5, August 2008 The Looming Crisis: Displacement and Security in Iraq Elizabeth G. Ferris -APOF)RAQ Map: ICG, “Iraq’s Civil War, the Sadrists, and the Surge.” Middle East Report No. 72, 7 February 2008. &OREIGN0OLICYAT"ROOKINGSIII ,ISTOF!CRONYMS AQI Al Qaeda in Iraq CAP Consolidated Appeals Process CPA Coalition Provisional Authority CRRPD Commission for the Resolution of Real Property Disputes EIA Energy Information Administration (U.S.) GOI Government of Iraq ICG International Crisis Group ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IDPs Internally Displaced Persons IOM International Organization for Migration IRIN Integrated Regional Information Service ITG Iraqi Transitional Government KRG Kurdistan Regional Government MNF-I Multi-National Force Iraq MoDM/MoM Ministry of Displacement and Migration (recently renamed Ministry of Migration) NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization NCCI NGO Coordination Committee in Iraq OCHA Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs PDS Public Distribution System PKK Kurdistan Workers’ Party PLO Palestinian Liberation Organization PRTs Provincial Reconstruction Teams RSG Representative of the Secretary-General TAL Transitional Administrative Law UIA United Iraqi Alliance UNAMI United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq UNDP United Nations Development Program UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund USAID U.S. Agency for International Development USG United States Government &OREIGN0OLICYAT"ROOKINGSV !WORDONTERMINOLOGY The term “displaced” is used here to refer to both refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) which have clear meanings in international law. -

L'exode Des « Plumes Indomptées »

Trimestriel Hiver 2014 2 € www.rsf.org LA REVUE DE REPORTERS SANS FRONTIÈRES POUR LA LIBERTÉ DE L’informaTION - N°09 PRIX REPORTERS SANS FRONTIÈRES SANJUANA MARTINEZ : « RSF M’A SAUVÉ LA VIE PLUS d’UNE FOIS » ÉTHIOPIE L’ExODE DES « PLUMES INDOMPTÉES » EN VUES 1. BAYEUX OU L’HOMMAGE AUX JOURNALISTES DISPARUS Le secrétaire général Christophe Deloire a dévoilé le 9 octobre 2014 à Bayeux la stèle des 113 noms de journalistes tués entre avril 2013 et août 2014. Un hommage particulier a été rendu à six d’entre eux : James Foley, décapité le 19 août par le groupe État islamique ; Camille Lepage, victime d’une fusillade en mai en Centrafrique ; Anja Niedringhaus, photographe allemande tuée en avril en Afghanistan ; Sardar Ahmad, abattu en Afghanistan en mars avec sa femme et deux de ses enfants par un commando taliban ; Ghislaine Dupont et Claude Verlon, journalistes à RFI assassinés au Mali en novembre 2013. © AFP PHOTO / CHARLY TRIBALLEAU / CHARLY © AFP PHOTO 2. #FIGHTIMPUNITY À l’occasion du 2 novembre 2014, première édition de la « Journée internationale de la fin de l’impunité pour les crimes commis contre les journalistes », Reporters sans frontières a lancé une campagne internationale intitulée #FightImpunity afin de faire pression sur les autorités pour traduire en justice les responsables de crimes contre les journalistes. La campagne se décline à travers dix cas d’impunité – torture, disparitions, assassinats -, et pointe du doigt les manquements des systèmes judiciaires et policiers. Les internautes ont pu agir à titre personnel en s’adressant directement par message électronique ou tweet aux chefs d’État ou de gouvernement des pays concernés.