And the Chilean Cueca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PF Vol19 No01.Pdf (12.01Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 19, No.1 Spring 1994 CONTENTS ARTICLES Wintering, the Outsider Adult Male and the Ethnogenesis of the Western Plains Metis John E. Foster 1 The Origins of Winnipeg's Packinghouse Industry: Transitions from Trade to Manufacture Jim Silver 15 Adapting to the Frontier Environment: Mixed and Dryland Farming near PincherCreek, 1895-1914 Warren M. Elofson 31 "We Are Sitting at the Edge of a Volcano": Winnipeg During the On-to-ottawa Trek S.R. Hewitt 51 Decision Making in the Blakeney Years Paul Barker 65 The Western Canadian Quaternary Place System R. Keith Semple 81 REVIEW ESSAY Some Research on the Canadian Ranching Frontier Simon M. Evans 101 REVIEWS DAVIS, Linda W., Weed Seeds oftheGreat Plains: A Handbook forIdentification by Brenda Frick 111 YOUNG, Kay, Wild Seasons: Gathering andCooking Wild Plants oftheGreat Plains by Barbara Cox-Lloyd 113 BARENDREGT, R.W., WILSON,M.C. and JANKUNIS, F.]., eds., Palliser Triangle: A Region in Space andTime by Dave Sauchyn 115 GLASSFORD, Larry A., Reaction andReform: ThePolitics oftheConservative PartyUnder R.B.Bennett, 1927-1938 by Lorne Brown 117 INDEX 123 CONTRIBUTORS 127 PRAIRIEFORUM:Journal of the Canadian Plains Research Center Chief Editor: Alvin Finkel, History, Athabasca Editorial Board: I. Adam, English, Calgary J.W. Brennan, History, Regina P. Chorayshi, Sociology, Winnipeg S.Jackel, Canadian Studies, Alberta M. Kinnear, History, Manitoba W. Last, Earth Sciences, Winnipeg P. McCormack, Provincial Museum, Edmonton J.N. McCrorie, CPRC, Regina A. Mills, Political Science, Winnipeg F. Pannekoek, Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism, Edmonton D. Payment, Parks Canada, Winnipeg T. Robinson, Religious Studies, Lethbridge L. Vandervort, Law, Saskatchewan J. -

Bronx Princess

POV Community Engagement & Education Discussion GuiDe Sweetgrass A Film by Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor www.pbs.org/pov POV BFIALcMKMgARKOEuRNSd’ S ITNAFTOERMMEANTTISON Boston , 2011 Recordist’s Statement We began work on this film in the spring of 2001. We were living in colorado at the time, and we heard about a family of nor - wegian-American sheepherders in Montana who were among the last to trail their band of sheep long distances — about 150 miles each year, all of it on hoof — up to the mountains for summer pasture. i visited the Allestads that April during lambing, and i was so taken with the magnitude of their life — both its allure and its arduousness — that we ended up following them, their friends and their irish-American hired hands intensely over the following years. to the point that they felt like family. Sweetgrass is one of nine films to have emerged from the footage we have shot over the last decade, the only one intended principally for theatrical exhibition. As the films have been shaped through editing, they seem to have become as much about the sheep as about their herders. the humans and animals that populate the footage commingle and crisscross in ways that have taken us by surprise. Sweetgrass depicts the twilight of a defining chapter in the history of the American West, the dying world of Western herders — descendants of scandinavian and northern european homesteaders — as they struggle to make a living in an era increasingly inimical to their interests. set in Big sky country, in a landscape of remarkable scale and beauty, the film portrays a lifeworld colored by an intense propinquity between nature and culture — one that has been integral to the fabric of human existence throughout history, but which is almost unimaginable for the urban masses of today. -

The Chilean Miracle

Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 1 The Chilean miracle PATRIMONIALISM IN A MODERN FREE-MARKET DEMOCRACY Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 2 The Chilean miracle Promotor: PATRIMONIALISM IN A MODERN Prof. dr. P. Richards FREE-MARKET DEMOCRACY Hoogleraar Technologie en Agrarische Ontwikkeling Wageningen Universiteit Copromotor: Dr. C. Kay Associate Professor in Development Studies Institute of Social Studies, Den Haag LUCIAN PETER CHRISTOPH PEPPELENBOS Promotiecommissie: Prof. G. Mars Brunel University of London Proefschrift Prof. dr. S.W.F. Omta ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor Wageningen Universiteit op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. dr. ir. J.D. van der Ploeg prof. dr. M. J. Kropff, Wageningen Universiteit in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 10 oktober 2005 Prof. dr. P. Silva des namiddags te vier uur in de Aula. Universiteit Leiden Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool CERES Proefschrift DEF stramien 14-09-2005 09:35 Pagina 4 Preface The work that follows is an attempt to blend together cultural anthropology with managerial sciences in a study of Chilean agribusiness and political economy. It also blends together theory and practice, in a new account of Chilean institutional culture validated through real-life consultancy experiences. This venture required significant cooperation from various angles. I thank all persons in Chile who contributed to the fieldwork for this study. Special Peppelenbos, Lucian thanks go to local managers and technicians of “Tomatio” - a pseudonym for the firm The Chilean miracle. Patrimonialism that cooperated extensively and became key subject of this study. -

Program Notes

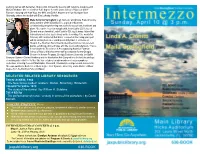

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO -

Permanent War on Peru's Periphery: Frontier Identity

id2653500 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ’S PERIPHERY: FRONT PERMANENT WAR ON PERU IER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH CENTURY CHILE. By Eugene Clark Berger Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Date: Jane Landers August, 2006 Marshall Eakin August, 2006 Daniel Usner August, 2006 íos Eddie Wright-R August, 2006 áuregui Carlos J August, 2006 id2725625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY ’ PERMANENT WAR ON PERU S PERIPHERY: FRONTIER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH-CENTURY CHILE EUGENE CLARK BERGER Dissertation under the direction of Professor Jane Landers This dissertation argues that rather than making a concerted effort to stabilize the Spanish-indigenous frontier in the south of the colony, colonists and indigenous residents of 17th century Chile purposefully perpetuated the conflict to benefit personally from the spoils of war and use to their advantage the resources sent by viceregal authorities to fight it. Using original documents I gathered in research trips to Chile and Spain, I am able to reconstruct the debates that went on both sides of the Atlantic over funds, protection from ’ th pirates, and indigenous slavery that so defined Chile s formative 17 century. While my conclusions are unique, frontier residents from Paraguay to northern New Spain were also dealing with volatile indigenous alliances, threats from European enemies, and questions about how their tiny settlements could get and keep the attention of the crown. -

Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez International Student Handbook

INTERNATIONAL STUDENT UNIVERSIDAD ADOLFO IBÁÑEZ / SANTIAGO · VIÑA DEL MAR / CHILE [ 1 WELCOME Over the last ten years, we have been working with our partner universities in both regular exchange programs as well as featured programs, offering courses of diverse topics and organizing cultural and athletic activities for our international students. Our goal is to support their advance, increase their skills of the Spanish language and foster friendship with Chilean students. All of these are the fundamental buildings blocks to have an unforgettable experience living in Chile. The key to achieving successful results has been a close and permanent relationship with our students and colleagues abroad, based on commitment and strong support. This is made possible due to the hard work of a dedicated faculty who invests an incredible amount of energy to share their passion for international education with students, as well as offering academically well-matched immersive study abroad programs that focus on quality, safety, diversity and accessibility. I believe that our international students will benefit from the high-level education and vigorous tradition of the Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez. Meanwhile, I suggest that students make the university their home, establishing open communication and learning with faculty and fellow students. I wish you great success studying at UAI. Sincerely, Gerardo Vidal G. Director Relaciones Internacionales Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez [ 2 WELCOME [ 3 CHILE CHILE is one of the most interesting countries of Latin America in terms of professional activities and tourism. A solid economy and spectacular landscapes make the country an exceptional place for living and traveling. Placed in South America, our country occupies a long, narrow strip of land between the Andes Mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. -

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago De Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space

Urban Ethnicity in Santiago de Chile Mapuche Migration and Urban Space vorgelegt von Walter Alejandro Imilan Ojeda Von der Fakultät VI - Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften Dr.-Ing. genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. -Ing. Johannes Cramer Berichter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Peter Herrle Berichter: Prof. Dr. phil. Jürgen Golte Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 18.12.2008 Berlin 2009 D 83 Acknowledgements This work is the result of a long process that I could not have gone through without the support of many people and institutions. Friends and colleagues in Santiago, Europe and Berlin encouraged me in the beginning and throughout the entire process. A complete account would be endless, but I must specifically thank the Programme Alßan, which provided me with financial means through a scholarship (Alßan Scholarship Nº E04D045096CL). I owe special gratitude to Prof. Dr. Peter Herrle at the Habitat-Unit of Technische Universität Berlin, who believed in my research project and supported me in the last five years. I am really thankful also to my second adviser, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Golte at the Lateinamerika-Institut (LAI) of the Freie Universität Berlin, who enthusiastically accepted to support me and to evaluate my work. I also owe thanks to the protagonists of this work, the people who shared their stories with me. I want especially to thank to Ana Millaleo, Paul Paillafil, Manuel Lincovil, Jano Weichafe, Jeannette Cuiquiño, Angelina Huainopan, María Nahuelhuel, Omar Carrera, Marcela Lincovil, Andrés Millaleo, Soledad Tinao, Eugenio Paillalef, Eusebio Huechuñir, Julio Llancavil, Juan Huenuvil, Rosario Huenuvil, Ambrosio Ranimán, Mauricio Ñanco, the members of Wechekeche ñi Trawün, Lelfünche and CONAPAN. -

De La Capilla De Músicos Al Buena Vista Social Club. Música, Etnia Y Sociedad En América Latina

Rev7-04 1/8/02 14:21 Página 187 Rainer Huhle De la Capilla de Músicos al Buena Vista Social Club. Música, etnia y sociedad en América Latina 1. El encuentro colonial El interés por la música “culta” durante los casi tres siglos de la época colonial en Amé- rica Latina, si bien es de fechas recientes, experimenta en la actualidad un auge casi vertigi- noso. Un repertorio hace pocos años casi desconocido ha encontrado el interés de los músi- cos y las empresas discográficas de tal manera que, para dar un ejemplo, una pequeña joya del repertorio virreinal peruano, el himno quechua Hanac Pachap que se encuentra en el Ritual Formulario e Institución de Curas (Lima 1631) del padre Juan Pérez Bocanegra, está disponible ahora en por lo menos una docena de diferentes grabaciones en CD. Esta popula- ridad de un repertorio no muy grande hace que no sólo los musicólogos sino también los intérpretes –que en el campo de la música antigua muchas veces también son investigado- res– estén buscando incansablemente nuevas piezas y nuevos elementos para demostrar la especificidad del repertorio americano. La producción de fuentes escritas sobre la música colonial y sus características queda un poco detrás de ese auge, aunque también se pueden notar grandes avances en la investigación que permiten un mejor entendimiento del contexto social e ideológico que dieron origen a esas obras. Año tras año se descubren nuevas obras, sabemos más de las biografías de los compositores –europeos y nativos– que trabajaban en las Américas. Y poco a poco se llega a dimensionar el aporte y el rol que las poblaciones indígenas (y negras) jugaron en ese contexto de la producción musical durante la colonia. -

International Communication Research Journal

International Communication Research Journal NON-PROFIT ORG. https://icrj.pub/ U.S. POSTAGE PAID [email protected] FORT WORTH, TX Department of Journalism PERMIT 2143 Texas Christian University 2805 S. University Drive TCU Box 298060, Fort Worth Texas, 76129 USA Indexed and e-distributed by: EBSCOhost, Communication Source Database GALE - Cengage Learning International Communication Research Journal Vol. 54, No. 2 . Fall 2019 Research Journal Research Communication International ISSN 2153-9707 ISSN Vol. 54, No. 2 54,No. Vol. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication inJournalismandMass Education for Association A publication of the International Communication Divisionofthe Communication of theInternational A publication . Fall 2019 Fall International Communication Research Journal A publication of the International Communication Division, Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC) Editor Uche Onyebadi Texas Christian University Associate Editors Editorial Consultant Ngozi Akinro Yong Volz Wayne Wanta Website Design & Maintenance Editorial University of Florida Texas Wesleyan University Missouri School of Journalism Editorial Assistant Book Review Editor Jennifer O’Keefe Zhaoxi (Josie) Liu Texas Christian University Editorial Advisory Board Jatin Srivastava, Lindita Camaj, Mohammed Al-Azdee, Ammina Kothari, Jeannine Relly, Emily Metzgar, Celeste Gonzalez de Bustamante, Yusuf Kalyango Jr., Zeny Sarabia-Panol, Margaretha Geertsema-Sligh, Elanie Steyn Editorial Review Board Adaobi Duru Gulilat Menbere Tekleab Mark Walters University of Louisiana, USA Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia Aoyama Gakuin University, Japan Ammina Kothari Herman Howard Mohamed A. Satti Rochester Institute of Technology, USA Angelo State University, USA American University of Kuwait, Kuwait Amy Schmitz Weiss Ihediwa Samuel Chibundu Nazmul Rony San Diego State University USA Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Slippery Rock University, USA Anantha S. -

Protocolo Para La Descripción Del Apero Del Huaso 2016

Protocolo para la descripción del apero del huaso 2016 Lorena Cordero Valdés BREVE HISTORIA DEL HUASO CHILENO os conquistadores españoles influyeron fuertemente en las costumbres y tradiciones presentes en la zona central de nuestro país, lo que condujo al mestizaje cultural, ya que el español debió integrarse a las costumbres de los indígenas para poder hacer posible la convivencia. Surge así la encomienda, que era la asignación de una cantidad de tierra e indios sobre los cuales el soldado español tenía dominio. De esta convivencia nace una raza mestiza entre conquistadores y conquistados. Si nos atenemos a su origen histórico y a elementos raciales que dieron origen al mestizo y que son los elementos ancestrales del huaso tales como padre español, pero no cualquiera de los españoles que llegaron durante la Conquista, sino andaluces con madre y abuela indias, sumado al medio ambiente en el que se desenvuelve su vida y la actividad agrícola a la que se dedica, se podría definir al huaso como un mestizo ascendente enriquecido y de vida rural. El mestizo ascendente tomó las costumbres y la idiosincrasia del padre español, más que de la madre india. Vivió con el padre o amparado por él, apegado a un pedazo de tierra, o junto a la madre que desempeñaba funciones domésticas en casa del español. Se crió en un ambiente español, oyendo y hablando su lengua, conociendo y practicando su religión, es decir, adquiriendo sus hábitos; con los años llegó a convertirse en un individuo nacido en Chile asimilado al español, que poco o nada tenía que ver con el indio, compenetrado del linaje paterno. -

Bases Xxxiii Festival Nacional De La Cueca Y La Tonada

BASES XXXIII FESTIVAL NACIONAL DE LA CUECA Y LA TON ADA INEDITA CONTEXTO La Ilustre Municipalidad de Valparaíso, junto a la Asociación Regional de Clubes de Cueca Quinta Región, han sido los gestores del “Festival Nacional de la Cueca y la Tonada Inédita”. Desde el año 1985 a la fecha, ya han transcurrido 32 años, realizando este magno evento en nuestro escenario natural, Caleta Portales, lugar típico de nuestro querido Puerto que es ciudad patrimonio de la Humanidad y capital cultural de Chile. El Festival tiene como fin convocar a distintos compositores, interpretes nacionales del folclor Chileno, para mostrar sus distintas creaciones q ue están llenas de creatividad, buscando la preservación de nuestras raíces folclóricas, enriqueciendo así, el patrimonio folclórico nacional mediante estas nuevas composiciones musicales y que podrán exponer en este tradicional Festival. DESCRIPCIÓN DE LA INSTITUCIÓN NOMBRE: ASOCIACION REGIONAL DE CLUBES DE CUECA V REGIÓN DIRECCIÓN: AVENIDA WASHINGTON Nº 16, VALPARAÍSO TELEFONO: 9 - 42594587 La Asociación Regional de Clubes de Cueca Quinta Región, fue fundada el día 21 de diciembre del año 1981, su personalidad jurídica Nº 1446 del 15 /12/1989. Actualmente cuenta con 13 Clubes Asociados con sus respectivas Personalidades Jurídicas, con ello se cumple el objetivo único y principal que es educar y mantener activas las tradiciones nacionales en los niños, jóvenes, adultos y adultos mayores. DIRECTIVA PRESIDENTE: Pedro Adolfo Guerrero Rivera. RUT 15.581.244 - 3 SECRETARIO: Nelson Delgado Almonacid. RUT 6.334.422 - 2 TESORERO: Freddy Méndez Madariaga RUT 9.735.118 - K CONVOCATORIA: Se invita a participar a los autores y compositores a nivel Nacional.