A Critical and Performance Edition of Agustin Barrios's Cueca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music of Latin America (In English)

Music of Latin America (in English) Class Code MUSIC – UA 9155 Instructor Juan Raffo Details Email: [email protected] Cell/WhatsApp: +54 911 6292 0728 Office Hours: Faculty Room, Wed 5-6 PM Class Details Mon/Wed 3:30-5:00 PM Location: Room Astor Piazzolla Prerequisites None Class A journey through the different styles of Latin American Popular Music (LAPM), Description particularly those coming from Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. Their roots, influences and characteristics. Their social and historical context. Their uniqueness and similarities. Emphasis in the rhythmic aspect of folk music as a foundation for dance and as a resource of cultural identity. Even though there is no musical prerequisite, the course is recommended for students with any kind and/or level of musical experience. The course explores both the traditional and the contemporary forms of LAPM. Extensive listening/analysis of recorded music and in-class performing of practical music examples will be primary features of the course. Throughout the semester, several guest musicians will be performing and/or giving clinic presentations to the class. A short reaction paper will be required after each clinic. These clinics might be scheduled in a different time slot or even day than the regular class meeting, provided that there is no time conflict with other courses for any of the students. Desired Outcomes ● Get in contact with the vast music culture of Latin America ● Have a hands-on approach to learn and understand music ● Be able to aurally recognize and identify Latin American music genres and styles Assessment 1. Attendance, class preparation and participation, reaction papers (online): Components 20 % 2. -

Historical Background

Historical Background Lesson 3 The Historical Influences… How They Arrived in Argentina and Where the Dances’ Popularity is Concentrated Today The Chacarera History: WHAT INFLUENCES MADE THE CHACARERA WHAT IT IS TODAY? HOW DID THESE INFLUENCES MAKE THEIR WAY INTO ARGENTINA? The Chacarera was influenced by the pantomime dances (the Gallarda, the Canario, and the Zarabanda) that were performed in the theaters of Europe (Spain and France) in the 1500s and 1600s. Later, through the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Chacarera spread from Peru into Argentina during the 1800s (19th century). As a result, the Chacarera was also influenced by the local Indian culture (indigenous people) of the area. Today, it is enjoyed by all social classes, in both rural and urban areas. It has spread throughout the entire country except in the region of Patagonia. Popularity is concentrated in which provinces? It is especially popular in Santiago del Estero, Tucuman, Salta, Jujuy, Catamarca, La Rioja and Cordoba. These provinces are located in the Northwest, Cuyo, and Pampas regions of Argentina. There are many variations of the dance that are influenced by each of the provinces (examples: The Santiaguena, The Tucumana, The Cordobesa) *variations do not change the essence of the dance The Gato History: WHAT INFLUENCES MADE THE GATO WHAT IT IS TODAY? HOW DID THESE INFLUENCES MAKE THEIR WAY INTO ARGENTINA? The Gato was danced in many Central and South American countries including Mexico, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay, however, it gained tremendous popularity in Argentina. The Gato has a very similar historical background as the other playfully mischievous dances (very similar to the Chacarera). -

La Asombrosa Excursión De Zamba: La Parodia Como Estrategia Educativa

La asombrosa excursión de Zamba: la parodia como estrategia educativa Germán Martínez Alonso ([email protected]) Estudiante avanzado de la licenciatura en Ciencias de la Comunicación (orientación en Comunicación y Procesos Educativos), Facultad de Ciencias Sociales (UBA). Participa del Proyecto UBACyT Regímenes de representación mediática: absorciones y transformaciones discursivas, dirigido por la profesora María Rosa del Coto. Pensar las relaciones entre comunicación y educación siempre implica enfrentarse a desafíos. Lejos de restringirse a la escolaridad, los fenómenos educativos contemporáneos están atravesados por procesos y sentidos complejos, propios de un auténtico ecosistema comunicativo (Martín-Barbero, 2002) que funciona como el escenario para el despliegue de nuestras vidas, y que conforma una parte significativa de nuestras dimensiones simbólicas. Partiendo de una visión amplia sobre la educación, que se opone a perspectivas restringidas1, entendemos que las reflexiones sobre las procesos educativos precisan ser formuladas en el marco de una sociedad que, en tanto constructora de sentidos comunes para los niños, se encuentra en permanente tensión con un entorno de hiperestimulación. Esto se debe a la frecuentación de y/o a la interacción con productos de los medios de comunicación, los videojuegos, las redes sociales online, etc., que contribuyen a moldear subjetividades e imaginarios. El reto, cuando se trata de investigar en educación, recae en los cambios de las temporalidades y las experiencias subjetivas, es decir, en la manera en que las diferentes generaciones se representan lo real-social. Partimos de una suposición inicial: creemos que las tópicas del imaginario social que conciernen a la creación y la producción mediática de la actualidad pueden ser detectadas a partir de la descripción de los mecanismos típicos de las prácticas discursivas. -

Program Notes

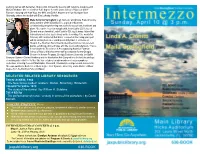

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO -

New York University in Buenos Aires the Music of Latin America (In English) V71.9155.002

New York University in Buenos Aires The Music of Latin America (in English) V71.9155.002 Professor: Juan Raffo Aug-Dec 2011 Office Hours: Mon & Thr 7-8 PM, by appointment Mon & Thr 3:30-5:00 PM [email protected] Room: Astor Piazzolla 1. Course Description: A journey through the different styles of Latin American Popular Music (LAPM), particularly those coming from Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. Their roots, influences and characteristics. Their social and historical context. Their uniqueness and similarities. Emphasis in the rhythmic aspect of folk music as a foundation for dance and as a resource of cultural identity. Even though there is no musical prerequisite, the course is recommended for students with any kind and/or level of musical experience. The course explores both the traditional and the comtemporary forms of LAPM Extensive listening/analysis of recorded music and in-class performing of practical music examples will be primary features of the course. Throughout the semester, several guest musicians will be performing and/or giving clinic presentations to the class. A short reaction paper will be required after each clinic. These clinics might be scheduled in a different time slot or even day than the regular class meeting, provided that is no time conflict with other courses for any of the students. Once a semester, the whole class will attend a public concert along with the professor. This field trip will replace a class session. Attendance is mandatory. In addition to that, students will be guided—and strongly encouraged—to go to public concerts and dance venues on their own. -

The Path of Beliefs. Some Determinants of Religious Mobility in Latin America

VOL. 31, ART. 3, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.1978 The Path of Beliefs. Some Determinants of Religious Mobility in Latin America El andar de las creencias. Algunos determinantes de la movilidad religiosa en América Latina Abbdel Camargo Martínez1 ABSTRACT The aim of this article is to highlight some of the causes that led to the increase of new religious expressions in Latin America, which may be different or complementary to the historically dominant religion, Roman Catholicism. The research uses a procedural analysis to show how a process of religious conversion and mobility occurred in the region. This has implications for the social structure of countries, as well as community identity, the definition of national history and religious faith, which adapts to the present-day needs of the population. Keywords: 1. religion, 2. change, 3. causes, 4. Mexico, 5. Latin America RESUMEN El objetivo de este trabajo es mostrar algunas causas del incremento de nuevas expresiones religiosas en Latinoamérica, mismas que pueden ser ajenas o complementarias al catolicismo romano, religión histórica y dominante en la región. A través de un análisis procesual, se observa cómo se ha establecido un proceso de conversión y movilidad religiosa en la región con implicaciones en la estructura social de los países, su identidad comunitaria, la definición de su historia y el campo confesional que se adecua a las necesidades actuales de los habitantes de los países de la región. Palabras clave: 1. religión, 2. cambio, 3. causas, 4. México, 5. América Latina. Date received: September 26th, 2017 Date accepted: January 25th, 2018 1 National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt), El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Ecosur), Mexico, [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8038-8089 Frontera Norte es una revista digital anual editada por El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. -

De La Capilla De Músicos Al Buena Vista Social Club. Música, Etnia Y Sociedad En América Latina

Rev7-04 1/8/02 14:21 Página 187 Rainer Huhle De la Capilla de Músicos al Buena Vista Social Club. Música, etnia y sociedad en América Latina 1. El encuentro colonial El interés por la música “culta” durante los casi tres siglos de la época colonial en Amé- rica Latina, si bien es de fechas recientes, experimenta en la actualidad un auge casi vertigi- noso. Un repertorio hace pocos años casi desconocido ha encontrado el interés de los músi- cos y las empresas discográficas de tal manera que, para dar un ejemplo, una pequeña joya del repertorio virreinal peruano, el himno quechua Hanac Pachap que se encuentra en el Ritual Formulario e Institución de Curas (Lima 1631) del padre Juan Pérez Bocanegra, está disponible ahora en por lo menos una docena de diferentes grabaciones en CD. Esta popula- ridad de un repertorio no muy grande hace que no sólo los musicólogos sino también los intérpretes –que en el campo de la música antigua muchas veces también son investigado- res– estén buscando incansablemente nuevas piezas y nuevos elementos para demostrar la especificidad del repertorio americano. La producción de fuentes escritas sobre la música colonial y sus características queda un poco detrás de ese auge, aunque también se pueden notar grandes avances en la investigación que permiten un mejor entendimiento del contexto social e ideológico que dieron origen a esas obras. Año tras año se descubren nuevas obras, sabemos más de las biografías de los compositores –europeos y nativos– que trabajaban en las Américas. Y poco a poco se llega a dimensionar el aporte y el rol que las poblaciones indígenas (y negras) jugaron en ese contexto de la producción musical durante la colonia. -

Andean Music, the Left and Pan-Americanism: the Early History

Andean Music, the Left, and Pan-Latin Americanism: The Early History1 Fernando Rios (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) In late 1967, future Nueva Canción (“New Song”) superstars Quilapayún debuted in Paris amid news of Che Guevara’s capture in Bolivia. The ensemble arrived in France with little fanfare. Quilapayún was not well-known at this time in Europe or even back home in Chile, but nonetheless the ensemble enjoyed a favorable reception in the French capital. Remembering their Paris debut, Quilapayún member Carrasco Pirard noted that “Latin American folklore was already well-known among French [university] students” by 1967 and that “our synthesis of kena and revolution had much success among our French friends who shared our political aspirations, wore beards, admired the Cuban Revolution and plotted against international capitalism” (Carrasco Pirard 1988: 124-125, my emphases). Six years later, General Augusto Pinochet’s bloody military coup marked the beginning of Quilapayún’s fifteen-year European exile along with that of fellow Nueva Canción exponents Inti-Illimani. With a pan-Latin Americanist repertory that prominently featured Andean genres and instruments, Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani were ever-present headliners at Leftist and anti-imperialist solidarity events worldwide throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Consequently both Chilean ensembles played an important role in the transnational diffusion of Andean folkloric music and contributed to its widespread association with Leftist politics. But, as Carrasco Pirard’s comment suggests, Andean folkloric music was popular in Europe before Pinochet’s coup exiled Quilapayún and Inti-Illimani in 1973, and by this time Andean music was already associated with the Left in the Old World. -

International Communication Research Journal

International Communication Research Journal NON-PROFIT ORG. https://icrj.pub/ U.S. POSTAGE PAID [email protected] FORT WORTH, TX Department of Journalism PERMIT 2143 Texas Christian University 2805 S. University Drive TCU Box 298060, Fort Worth Texas, 76129 USA Indexed and e-distributed by: EBSCOhost, Communication Source Database GALE - Cengage Learning International Communication Research Journal Vol. 54, No. 2 . Fall 2019 Research Journal Research Communication International ISSN 2153-9707 ISSN Vol. 54, No. 2 54,No. Vol. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication inJournalismandMass Education for Association A publication of the International Communication Divisionofthe Communication of theInternational A publication . Fall 2019 Fall International Communication Research Journal A publication of the International Communication Division, Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC) Editor Uche Onyebadi Texas Christian University Associate Editors Editorial Consultant Ngozi Akinro Yong Volz Wayne Wanta Website Design & Maintenance Editorial University of Florida Texas Wesleyan University Missouri School of Journalism Editorial Assistant Book Review Editor Jennifer O’Keefe Zhaoxi (Josie) Liu Texas Christian University Editorial Advisory Board Jatin Srivastava, Lindita Camaj, Mohammed Al-Azdee, Ammina Kothari, Jeannine Relly, Emily Metzgar, Celeste Gonzalez de Bustamante, Yusuf Kalyango Jr., Zeny Sarabia-Panol, Margaretha Geertsema-Sligh, Elanie Steyn Editorial Review Board Adaobi Duru Gulilat Menbere Tekleab Mark Walters University of Louisiana, USA Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia Aoyama Gakuin University, Japan Ammina Kothari Herman Howard Mohamed A. Satti Rochester Institute of Technology, USA Angelo State University, USA American University of Kuwait, Kuwait Amy Schmitz Weiss Ihediwa Samuel Chibundu Nazmul Rony San Diego State University USA Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Slippery Rock University, USA Anantha S. -

Bases Xxxiii Festival Nacional De La Cueca Y La Tonada

BASES XXXIII FESTIVAL NACIONAL DE LA CUECA Y LA TON ADA INEDITA CONTEXTO La Ilustre Municipalidad de Valparaíso, junto a la Asociación Regional de Clubes de Cueca Quinta Región, han sido los gestores del “Festival Nacional de la Cueca y la Tonada Inédita”. Desde el año 1985 a la fecha, ya han transcurrido 32 años, realizando este magno evento en nuestro escenario natural, Caleta Portales, lugar típico de nuestro querido Puerto que es ciudad patrimonio de la Humanidad y capital cultural de Chile. El Festival tiene como fin convocar a distintos compositores, interpretes nacionales del folclor Chileno, para mostrar sus distintas creaciones q ue están llenas de creatividad, buscando la preservación de nuestras raíces folclóricas, enriqueciendo así, el patrimonio folclórico nacional mediante estas nuevas composiciones musicales y que podrán exponer en este tradicional Festival. DESCRIPCIÓN DE LA INSTITUCIÓN NOMBRE: ASOCIACION REGIONAL DE CLUBES DE CUECA V REGIÓN DIRECCIÓN: AVENIDA WASHINGTON Nº 16, VALPARAÍSO TELEFONO: 9 - 42594587 La Asociación Regional de Clubes de Cueca Quinta Región, fue fundada el día 21 de diciembre del año 1981, su personalidad jurídica Nº 1446 del 15 /12/1989. Actualmente cuenta con 13 Clubes Asociados con sus respectivas Personalidades Jurídicas, con ello se cumple el objetivo único y principal que es educar y mantener activas las tradiciones nacionales en los niños, jóvenes, adultos y adultos mayores. DIRECTIVA PRESIDENTE: Pedro Adolfo Guerrero Rivera. RUT 15.581.244 - 3 SECRETARIO: Nelson Delgado Almonacid. RUT 6.334.422 - 2 TESORERO: Freddy Méndez Madariaga RUT 9.735.118 - K CONVOCATORIA: Se invita a participar a los autores y compositores a nivel Nacional. -

Poder Y Estudios De Las Danzas En El Perú

!"! " !# $ ! " # $ %&&'( A Carmen y Lucho 2 CONTENIDO Resumen……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Introducción…………………………………………………………………………… 5 1. Inicio de los estudios de las danzas y el problema nacional (1900-1941).......................................................................................... 9 2. Avances en los estudios de las danzas, influencia de la antropología culturalista y continuación del debate sobre lo nacional (1942-1967)........................................................ 18 3. Estudios de las danzas y nacionalismo popular (1968-1980)…………………………………………………………....................... 37 4. Institucionalización de los estudios de las danzas (1981-2005)...................................................................................................... 48 Conclusiones: Hacia un balance preliminar de los estudios de las danzas en el Perú.................................................................... 62 Referencias bibliográficas................................................................................. 68 3 Resumen Esta investigación trata sobre las relaciones que se establecen entre el poder y los estudios de las danzas en el Perú, que se inician en las primeras décadas del siglo XX y continúan hasta la actualidad, a través del análisis de dos elementos centrales: El análisis del contexto social, político y cultural en que dichos estudios se realizaron; y el análisis del contenido de dichos estudios. El análisis evidencia y visibiliza las relaciones de poder no manifiestan