La Nueva Canción and Its Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dans La Cantata Popular Santa María De Iquique

06,2 I 2021 Archiv für Textmusikforschung Identité(s) et mémoire(s) dans la Cantata popular Santa María de Iquique Olga LOBO (Grenoble)11 Summary The Cantata popular de Santa María de Iquique is one of the most important musical compositions of Quilapayún. Composed by Luis Advis in 1969 it tells the story of the massacre of the Iquique mineworkers in 1907. This cantata popular has become not only one of the symbols of the protest songs from the Seventies but also an icon for the universal struggle against injustice. The aim of this article is to study its history and different meanings in order to show the way how poetry, lyrics and music come together to tell the identities and memories of the Chilean people until now, when we celebrate its 50th anniversary. La Cantata de Luis Advis, une composition hybride et populaire La Cantata, entre deux traditions Interprétée pour la première fois en 1970 par le groupe Quilapayún, La Cantata popular Santa María de Iquique (Cantata) est une composition de Luis Advis (Iquique, 1935 – Santiago du Chili, 2005). Musicien autodidacte, il suivra dans les années 1950, une fois arrivé à Santiago, une formation classique avec Gustavo Becerra ou Albert Spikin. Si la tradi- tion classique sera déterminante pour la suite de sa carrière, les rythmes latino-américains ne font leur apparition dans le spectre de ses intérêts musicaux qu’à partir des années soixante. Son intérêt pour cette culture populaire était cependant tout relatif. Évoquant la genèse de la Cantata (dans une lettre du 15 mars 1984, envoyée à Eduardo Carrasco) Advis affirmera qu’à cette période-là il était un musicien « muy poco conocedor de la realidad popular musical y artística de [su] país » (Advis 2007, 16). -

Periférica 2020 320-330.Pdf

/ AUTORA / CORREO-E María Paulina Soto Labbé. [email protected] / ADSCRIPCIÓN PROFESIONAL Doctora en la Universidad de las Artes de Ecuador. / TÍTULO FONDART: Balance político de un instrumento de fi nanciamiento cultural del Chile 1990-2010. / RESUMEN Analizamos tendencias internacionales de fi nanciación instrumento de fi nanciación analizado; y establecemos una sectorial; cuestionamos el carácter de política pública del relación entre el principio político-ideológico neoliberal Sub- instrumento Fondo Nacional de las Artes y la Cultura FON- sidiariedad y el crecimiento asimétrico que esta genera. El DART; evaluamos la relación crecimiento y profesionaliza- presente artículo es resultado de una investigación realizada ción sectorial respecto del aumento de exigencias sobre el en el año 2011. / PALABRAS CLAVE Financiamiento de la cultura; fondos concursables de cultura; subsidio en cultura. / Artículo recibido: 20/10/2020 / Artículo aceptado: 03/11/2020 / AUTHOR / E-MAIL María Paulina Soto Labbé. [email protected] / PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATION Doctor at the University of the Arts of Ecuador. / TITLE FONDART: Political balance of a cultural fi nancing instrument in Chile 1990-2010 . / ABSTRACT We analyze international trends in sector fi nancing; We in demands on the fi nancing instrument analyzed; and we question the character of public policy of the instrument establish a relationship between the neoliberal political- National Fund for Arts and Culture of Chile FONDART; ideological principle Subsidiarity and the asymmetric growth We evaluate the relationship between growth and that it generates. This article is the result of an investigation professionalization in the sector and its eff ects on the increase carried out in 2011. / KEYWORDS Financing of culture; competitive culture funds; subsidy in culture. -

PF Vol19 No01.Pdf (12.01Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 19, No.1 Spring 1994 CONTENTS ARTICLES Wintering, the Outsider Adult Male and the Ethnogenesis of the Western Plains Metis John E. Foster 1 The Origins of Winnipeg's Packinghouse Industry: Transitions from Trade to Manufacture Jim Silver 15 Adapting to the Frontier Environment: Mixed and Dryland Farming near PincherCreek, 1895-1914 Warren M. Elofson 31 "We Are Sitting at the Edge of a Volcano": Winnipeg During the On-to-ottawa Trek S.R. Hewitt 51 Decision Making in the Blakeney Years Paul Barker 65 The Western Canadian Quaternary Place System R. Keith Semple 81 REVIEW ESSAY Some Research on the Canadian Ranching Frontier Simon M. Evans 101 REVIEWS DAVIS, Linda W., Weed Seeds oftheGreat Plains: A Handbook forIdentification by Brenda Frick 111 YOUNG, Kay, Wild Seasons: Gathering andCooking Wild Plants oftheGreat Plains by Barbara Cox-Lloyd 113 BARENDREGT, R.W., WILSON,M.C. and JANKUNIS, F.]., eds., Palliser Triangle: A Region in Space andTime by Dave Sauchyn 115 GLASSFORD, Larry A., Reaction andReform: ThePolitics oftheConservative PartyUnder R.B.Bennett, 1927-1938 by Lorne Brown 117 INDEX 123 CONTRIBUTORS 127 PRAIRIEFORUM:Journal of the Canadian Plains Research Center Chief Editor: Alvin Finkel, History, Athabasca Editorial Board: I. Adam, English, Calgary J.W. Brennan, History, Regina P. Chorayshi, Sociology, Winnipeg S.Jackel, Canadian Studies, Alberta M. Kinnear, History, Manitoba W. Last, Earth Sciences, Winnipeg P. McCormack, Provincial Museum, Edmonton J.N. McCrorie, CPRC, Regina A. Mills, Political Science, Winnipeg F. Pannekoek, Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism, Edmonton D. Payment, Parks Canada, Winnipeg T. Robinson, Religious Studies, Lethbridge L. Vandervort, Law, Saskatchewan J. -

Violeta Parra, Después De Vivir Un Siglo

En el documental Violeta más viva que nunca, el poeta Gonzalo Rojas llama a Violeta la estrella mayor de Chile, lo más grande, la síntesis perfecta. Esta elocuente descripción habla del sitial privilegiado que en la actualidad, por fin, ocupa Violeta Parra en nuestro país, después de muchos años injustos en los que su obra fue reconocida en el extranjero y prácticamente ignorada en Chile. Hoy, reconocemos a Violeta como la creadora que hizo de lo popular una expre- sión vanguardista, llena de potencia e identidad, pero también como un talento universal, singular y, quizás, irrepetible. Violeta fue una mujer que logró articular en su arte corrientes divergentes, obligándonos a tomar conciencia sobre la diversidad territorial y cultural del país que, además de valorar sus saberes originarios, emplea sus recursos para pavimentar un camino hacia la comprensión y valoración de lo otro. Para ello, tendió un puente entre lo campesino y lo urbano, asumiendo las antiguas tradi- ciones instaladas en el mundo campesino, pero también, haciendo fluir y trans- formando un patrimonio cultural en diálogo con una conciencia crítica. Además, construyó un puente con el futuro, con las generaciones posteriores a ella, y también las actuales, que reconocen en Violeta Parra el canto valiente e irreve- rente que los conecta con su palabra, sus composiciones y su música. Pero Violeta no se limitó a narrar costumbres y comunicar una filosofía, sino que también se preocupó de exponer, reflexionar y debatir sobre la situación política y social de la época que le tocó vivir, desarrollando una conciencia crítica, fruto de su profundo compromiso social. -

Las Cuecas Como Representaciones Estético-Políticas De Chilenidad En

Las cuecas como representaciones estético-políticas de chilenidad… / Revista Musical Chilena Las cuecas como representaciones estético-políticas de chilenidad en Santiago entre 1979 y 1989 The Cuecas as Aesthetic and Political Representation of Chilenidad in Santiago Between 1979 and 1989 por Araucaria Rojas Sotoconil Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile [email protected] El siguiente texto pretende dar cuenta de los lugares por los que se desplazaron las cuecas como repre- sentaciones estético-políticas de chilenidad durante el período de la dictadura militar, más específicamente en Santiago entre 1979 y 1989. Es desde allí donde se establece un derrotero autori- tario que, a través de múltiples mecanismos, dispone una fusión forzosa entre determinado “tipo” de hacer-cueca y las prolongaciones “cultural”-identitarias de las que el régimen se apropia. La cueca, en tanto dispositivo político de determinada oficialidad y las cuecas como formas particulares que se exce- den de sus ordenamientos son las que pretenden ser aquí visitadas: cueca sola, cuecas de barrios populares (también nombradas brava y chora), adicionada a cuecas decididamente militantes de la resistencia, se disponen como actos y realidades que pugnan y plurifican el acto de cuequear. Palabras clave: cueca, chilenidad, dictadura, clandestinidad. The following article has the purpose of analysing the various meanings of the cuecas as aesthetic and political representations of chilenidad during the period of the military dictatorship, more specifically in Santiago between 1979 and 1989. It was then that an authoritarian procedure was created which by means of multiple mechanisms imposed the mingling between a certain type of cueca making and the cultural identity of the cueca assumed by the military government as part of its communication policies. -

Bronx Princess

POV Community Engagement & Education Discussion GuiDe Sweetgrass A Film by Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor www.pbs.org/pov POV BFIALcMKMgARKOEuRNSd’ S ITNAFTOERMMEANTTISON Boston , 2011 Recordist’s Statement We began work on this film in the spring of 2001. We were living in colorado at the time, and we heard about a family of nor - wegian-American sheepherders in Montana who were among the last to trail their band of sheep long distances — about 150 miles each year, all of it on hoof — up to the mountains for summer pasture. i visited the Allestads that April during lambing, and i was so taken with the magnitude of their life — both its allure and its arduousness — that we ended up following them, their friends and their irish-American hired hands intensely over the following years. to the point that they felt like family. Sweetgrass is one of nine films to have emerged from the footage we have shot over the last decade, the only one intended principally for theatrical exhibition. As the films have been shaped through editing, they seem to have become as much about the sheep as about their herders. the humans and animals that populate the footage commingle and crisscross in ways that have taken us by surprise. Sweetgrass depicts the twilight of a defining chapter in the history of the American West, the dying world of Western herders — descendants of scandinavian and northern european homesteaders — as they struggle to make a living in an era increasingly inimical to their interests. set in Big sky country, in a landscape of remarkable scale and beauty, the film portrays a lifeworld colored by an intense propinquity between nature and culture — one that has been integral to the fabric of human existence throughout history, but which is almost unimaginable for the urban masses of today. -

Como Aprendí a Ser Chileno

www.ssoar.info Como aprendí a ser chileno - Wie ich lernte, Chilene zu sein Eichin, Pavel Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: Verlag Barbara Budrich Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Eichin, P. (2016). Como aprendí a ser chileno - Wie ich lernte, Chilene zu sein. PERIPHERIE - Politik, Ökonomie, Kultur, 36(3), 504-521. https://doi.org/10.3224/peripherie.v36i144.25719 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-SA Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-SA Licence Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. (Attribution-ShareAlike). For more Information see: Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-58841-1 Essay Pavel Eichin Como aprendí a ser chileno – Wie ich lernte, Chilene zu sein Zum 40. Jahrestag des Putsches vom 11. September 1973 gegen die Regie- rung Salvador Allendes und das linke Wahlbündnis Unidad Popular fand in Frankfurt am Main der Thementag „Chile im Wandel“1 statt. In diesem Kon- text wurde ich gebeten, einen Workshop zu leiten, in dem es um die Thematik des chilenischen Exils aus der Perspektive der „zweiten Generation“ ging. Dabei sollte ich meine subjektiven Erfahrungen und Beobachtungen als Teil dieser Generation einbringen und aus „soziologischer Distanz“ refl ektieren. Der Diskussion im Workshop verdanke ich weitere Überlegungen, die auch in diesen Text eingegangen sind. -

Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brad T. Eidahl December 2017 © 2017 Brad T. Eidahl. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile by BRAD T. EIDAHL has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. Barr-Melej Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EIDAHL, BRAD T., Ph.D., December 2017, History Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. Barr-Melej This dissertation examines the struggle between Chile’s opposition press and the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). It argues that due to Chile’s tradition of a pluralistic press and other factors, and in bids to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy, Pinochet and his top officials periodically demonstrated considerable flexibility in terms of the opposition media’s ability to publish and distribute its products. However, the regime, when sensing that its grip on power was slipping, reverted to repressive measures in its dealings with opposition-media outlets. Meanwhile, opposition journalists challenged the very legitimacy Pinochet sought and further widened the scope of acceptable opposition under difficult circumstances. Ultimately, such resistance contributed to Pinochet’s defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, initiating the return of democracy. -

Profesor Marcelo Galaz Vera Guía De Retroalimentación 7° Básico

Profesor Marcelo Galaz Vera COLEGIO SANTA FILOMENA Guía de retroalimentación 7° básico Nombre: ________________________________________________________________________ Curso: 7° año básico. Objetivo: : Reconocer el rol de la música en la sociedad de Chile, considerando sus propias experiencias musicales, contextos en que surge y valorar a las personas que la cultivan nuestra música chilena Lee atentamente y reflexiona para que contestes las siguientes preguntas: Música de raíz folclórica: Música típica : “A partir de los años 1920, se produjo en Chile un renacimiento en el interés por la música folclórica. Este renacimiento fue gestado por la aparición de nuevos grupos musicales, entre los que se destacó desde un comienzo el conjunto Los Cuatro Huasos (este grupo nació en 1927 y permaneció vigente, aunque con cambios en sus integrantes hasta 1956) seguidos posteriormente por otros como Ester Sore, Los de Ramón, Los Huasos Quincheros, El Dúo Rey Silva, Los Perlas, Silvia Infantas y los Cóndores, y Francisco Flores del Campo. Junto a los conjuntos musicales, el interés por el folclore surgió también en compositores e investigadores del folclore, entre los que cabe destacar a Raúl de Ramón, Luis Aguirre Pinto, Gabriela Pizarro entre muchos otros que aportaron en la recuperación de la música folclórica. Esta música era presentada como una versión refinada del folclore del campo, una adaptación para las radios o un espectáculo estilizado de la vida campesina, para gustar en la ciudad, en vez de un fiel reflejo del folclore rural. Durante las décadas de 1940 y 1950 este movimiento se volvió un emblema nacional. Entre las características de esta nueva tendencia folclórica, está la idealización de la vida rural, con temas románticos y patrióticos,60 ignorando la dura vida del trabajador rural. -

Belonging and Popular Culture Interdisciplines 1 (2018)

Lindholm, Belonging and popular culture InterDisciplines 1 (2018) Belonging and popular culture The work of Chilean artist Ana Tijoux Susan Lindholm Introduction Current public debates on migration in the Global North often focus on issues of integration and multiculturalism, that is, questions surrounding the reassertion of national identity and definitions of the nation-state. In these debates, the figure of the embodied and imagined migrant can be seen as one that serves to condense »concerns with race, space and time and the politics of belonging« (Westwood and Phizacklea 2000, 3). How- ever, these public debates tend to pay less attention to the experience of individual migrants and groups who move across national borders and the structural preconditions based on social issues such as race, culture, and gender they encounter and negotiate. In order to be able to discuss and theoretically frame such experiences, researchers have suggested moving beyond methodological nationalism by, for instance, identifying and analyzing different spaces in which individuals identified as the cultural or racial »Other« express experiences of marginalization and exclusion (Westwood and Phizacklea 2000; Anthias 2008; Amelina et al. 2012; Nowicka and Cieslik 2014; Vasilev 2018). While hip-hop culture is often described as a platform through which marginalized youths are able to make such experiences of social exclusion visible, it is also a highly gendered space that, in its mainstream version, is filled with expressions of hypermasculinity and misogyny (Kumpf 2013, 207; Sernhede and Söderman 2010, 51). Such dominance of masculine- coded expressions, in turn, contributes to the marginalization of female and queer artists in mainstream hip-hop culture (Rose 2008; Pough 2007). -

Program Notes

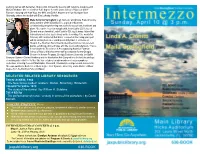

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO