New Maps of Longing My Whole Understanding Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Progress Until a Nation Examines Past

Soon From LAHORE & KARACHI A sister publication of CENTRELINE & DNA News Agency www.islamabadpost.com.pk ISLAMABAD EDITION IslamabadMonday, March 01, 2021 Pakistan’s First AndP Only DiplomaticO Daily STPrice Rs. 20 Info Minister Direct flights to PIO Sohail Shibli Faraz leads boost Pakistan- Ali Khan from the front Kyrgyzstan links gets Grade 21 Detailed News On Page-05 Detailed News On Page-08 Detailed News On Page-02 Briefs No progress DNA PDM fighting for improved until a nation system examines past DNA ISLAMABAD: Pakistan The PM was addressing the inauguration Muslim League- ceremony of the Al-Beruni Radius N a w a z (PML-N) heritage trail at Nandana fort in Jhelum leader and former Prime Minister (PM) Sha- abiD raza Petrol prices to hid Khaqan Abbasi on Sun- day has said that everyone JEHLUM: Prime Minister Imran Khan said remain same will see what will happen on Sunday that an examination of the past in the Senate polls. The was very important for a nation to progress and emphasised the value of future genera- DNa JHELUM: Prime Minister Imran Khan being briefed after performing groundbreaking PML-N leader expressed of restoration project for Al-Beruni Radius in Tilla Joggian. – DNA hope that Pakistan Peoples tions knowing about their history. ISLAMABAD: The prices of petroleum Party (PPP) leader and The prime minister was addressing the inau- products will remain the same for the month joint candidate of opposi- guration ceremony of the Al-Beruni Radius of March, according to Prime Minister Im- MQM tion’s Pakistan Democratic heritage trail at Nandana fort in Jhelum. -

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research ABSTRACT This report documents the technical support provided by the Design Team, deployed by CDPR, and covers the recommendations for institutional and regulatory reforms as well as a proposed private sector participation framework for tourism sector in Punjab, in the context of religious tourism, to stimulate investment and economic growth. Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project ---------------------- (Back of the title page) ---------------------- This page is intentionally left blank. 2 Consortium for Development Policy Research Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS 56 LIST OF FIGURES 78 LIST OF TABLES 89 LIST OF BOXES 910 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1112 1 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 1819 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1819 1.2 PAKISTAN’S TOURISM SECTOR 1819 1.3 TRAVEL AND TOURISM COMPETITIVENESS 2324 1.4 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF TOURISM SECTOR 2526 1.4.1 INTERNATIONAL TOURISM 2526 1.4.2 DOMESTIC TOURISM 2627 1.5 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL HERITAGE / RELIGIOUS TOURISM 2728 1.5.1 SIKH TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 2930 1.5.2 BUDDHIST TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 3536 1.6 DEVELOPING TOURISM - KEY ISSUES & CHALLENGES 3738 1.6.1 CHALLENGES FACED BY TOURISM SECTOR IN PUNJAB 3738 1.6.2 CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO HERITAGE TOURISM 3940 2 EXISTING INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM SECTOR 4344 2.1 CURRENT INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 4344 2.1.1 YOUTH AFFAIRS, SPORTS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND TOURISM -

1.Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth.Cdr

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Consortium for c d p r Development Policy Research w w w . c d p r . o r g . p k c d p r Report R1703 State June 2017 About the project The final report Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth has been completed by the CDPR team under overall guidance Funded by: World Bank from Suleman Ghani. The team includes Aftab Rana, Fatima Habib, Hina Shaikh, Nazish Afraz, Shireen Waheed, Usman Key Counterpart: Government of Khan, Turab Hussain and Zara Salman. The team would also +924235778180 [email protected] Punjab like to acknowledge the advisory support provided by . Impact Hasaan Khawar and Ali Murtaza. Dr. Ijaz Nabi (IGC and With assistance from CDPR) provided rigorous academic oversight of the report. CDPR, Government of Punjab has formulated a n d a p p r o v e d k e y principles of policy for tourism, providing an In brief anchor for future reforms Ÿ Government of Punjab is keen and committed to and clearly articulating i t s c o m m i t m e n t t o developing a comprehensive strategy for putting p r o m o t e t o u r i s m , tourism on a solid footing. e s p e c i a l l y h e r i t a g e Ÿ CDPR has been commissioned by the government to tourism. Government of help adopt an informed, contemporary, view of tourism Punjab has been closely involved in formulation of and assist in designing a reform program to modernize www.cdpr.org.pk f o l l o w - u p the sector. -

Remaking of Meos Identity: an Analysis

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(3): 3711 -3724 ISSN: 00333077 Remaking of MEOs Identity: An Analysis Dr. Jai Kishan Bhardwaj Assistant Professor, Institute of Law, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra ABSTRACT The paper revolves around the issue of bargaining power. It is highlighted with the example of Meos of Mewat that the process of making of more Muslim identity of the poor, backward strata of Muslims i.e. of Meos is nothing but gaining of bargaining power by elitist Muslims. The going on process is continue even more dangerous today which was initiated mostly in 1920’s. How Hindu cadres were engaged in reconversion of Meos with the help of princely Hindu states of Alwar and Bharatpur in the leadership of Swami Shardhanand and Meos were taught about their glorious Hindu past. With the passage of time, Hindu efforts in the region proved to be short-lived but Islamic one i.e. Tablighi Jamaat still continues in its practice and they have been successful in their mission to a great extent. The process of Islamisation has affected the Meos identity at different levels. The paper successfully highlights how the Meo identity has shaped as Muslim identity with the passage of time. It is also pointed out that Indian Muslim identity has reshaped with the passage of time due to some factors. The author asserts that the assertion of religious identity in the process of democratisation and modernisation should be seen as a method by which deprived communities in a backward society seek to obtain a greater share of power, government jobs and economic resources. -

BEYOND RELIGION in INDIA and PAKISTAN Gender and Caste, Borders and Boundaries Beyond Religion in India and Pakistan

BLOOMSBURY STUDIES IN RELIGION, GENDER AND SEXUALITY Navtej K. Purewal & Virinder S. Kalra BEYOND RELIGION IN INDIA AND PAKISTAN Gender and Caste, Borders and Boundaries Beyond Religion in India and Pakistan 9781350041752_txt_final.indd 1 24-09-2019 21:23:27 Bloomsbury Studies in Religion, Gender, and Sexuality Series Editors: Dawn Llewellyn, Sîan Hawthorne and Sonya Sharma This interdisciplinary series explores the intersections of religions, genders, and sexualities. It promotes the dynamic connections between gender and sexuality across a diverse range of religious and spiritual lives, cultures, histories, and geographical locations, as well as contemporary discourses around secularism and non-religion. The series publishes cutting-edge research that considers religious experiences, communities, institutions, and discourses in global and transnational contexts, and examines the fluid and intersecting features of identity and social positioning. Using theoretical and methodological approaches from inter/transdisciplinary perspectives, Bloomsbury Studies in Religion, Gender, and Sexuality addresses the neglect of religious studies perspectives in gender, queer, and feminist studies, and offers a space in which gender-critical approaches to religions engage with questions of intersectionality, particularly with respect to critical race, disability, post-colonial and decolonial theories. 9781350041752_txt_final.indd 2 24-09-2019 21:23:27 Beyond Religion in India and Pakistan Gender and Caste, Borders and Boundaries Virinder S. Kalra and Navtej K. Purewal 9781350041752_txt_final.indd 3 24-09-2019 21:23:27 BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2020 Copyright © Virinder S. -

The Persistence of Caste

Volume 01 :: Issue 01 February 2020 ISSN 2639-4928 THE PERSISTENCE OF CASTE EDITORIAL Why a Journal on Caste Laurence Simon, Sukhadeo Thorat FELICITATION His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama ARTICLES Recasting Food: An Ethnographic Study on How Caste and Resource Inequality Perpetuate Social Disadvantage in India Nakkeeran N, Jadhav S, Bhattacharya A, Gamit S, Mehta C, Purohit P, Patel R and Doshi M A Commentary on Ambedkar’s Posthumously Published “Philosophy of Hinduism” Rajesh Sampath Population - Poverty Linkages and Health Consequences: Understanding Global Social Group Inequalities Sanghmitra Sheel Acharya Painting by Savi Sawarkar Nationalism, Caste-blindness and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-war Jaffna Society, Sri Lanka Kalinga Tudor Silva FORUM The Revolt of the Upper Castes Jean Drèze Caste, Religion and Ethnicity: Role of Social Determinants in Accessing Rental Housing Vinod Kumar Mishra BOOK REVIEWS Indian Political Theory: Laying Caste and Consequences: Looking Through the Lens of Violence G. C. Pal the Groundwork for Svaraj Aakash Singh Rathore As a Dalit Woman: My Life in a Caste-Ghetto of Kerala Maya Pramod, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2019 Award Gendering Caste: Through a Feminist Lens Uma Chakravarti Mirrors of the Soul: Performative Egalitarianisms and Genealogies The Empire of Disgust: of the Human in Colonial-era Travancore, 1854-1927 Vivek V. Narayan, Prejudice, Discrimination, Bluestone Rising Scholar 2019 Award and Policy in India and the US Hasan, Z., Huq,Volume A., Nussbaum, 01 :: Issue 01 February 2020 ISSN 2639-4928 Volume 01 :: Issue 01 February 2020 ISSN 2639-4928 In THENāki’s Wake: PERSISTENCE Slavery and Caste Supremacy inOF the American CASTE Ceylon M., Verma, V. -

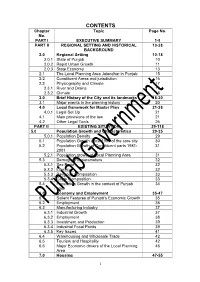

CONTENTS Chapter Topic Page No

CONTENTS Chapter Topic Page No. No. PART I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1-9 PART II REGIONAL SETTING AND HISTORICAL 10-28 BACKGROUND 2.0 Regional Setting 10-18 2.0.1 State of Punjab 10 2.0.2 Rapid Urban Growth 11 2.0.3 State Economy 13 2.1 The Local Planning Area Jalandhar in Punjab 15 2.2 Constituent Areas and jurisdiction 16 2.3 Physiography and Climate 17 2.3.1 River and Drains 17 2.3.2 Climate 18 3.0 Brief History of the City and its landmarks 18-20 3.1 Major events in the planning history 20 4.0 Legal framework for Master Plan 21-28 4.0.1 Legal Set Up 21 4.1 Main provisions of the law 21 4.2 Other Legal Tools 26 PART III EXISTING SITUATION 29-118 5.0 Population Growth and Characteristics 29-35 5.0.1 Population Density 29 5.1 Population Growth since 1901 of the core city 30 5.2 Population Growth of Constituent parts 1981- 31 2001 5.2.1 Population growth of Local Planning Area 31 5.3 Demographic parameters 32 5.3.1 Sex Ratio 32 5.3.2 Literacy 32 5.3.3 Religious Composition 33 5.3.4 Caste Composition 33 5.4 Population Growth in the context of Punjab 34 state 6.0 Economy and Employment 35-47 6.1 Salient Features of Punjab’s Economic Growth 35 6.2 Employment 36 6.3 Manufacturing Industry 37 6.3.1 Industrial Growth 37 6.3.2 Employment 38 6.3.3 Investment and Production 39 6.3.4 Industrial Focal Points 39 6.3.5 Key Issues 41 6.4 Warehousing and Wholesale Trade 42 6.5 Tourism and Hospitality 42 6.6 Major Economic drivers of the Local Planning 46 Area 7.0 Housing 47-55 1 7.0.1 Growth of Housing in Jalandhar 48 7.0.2 Pattern of using Housing stock 51 -

Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

All Rights Reserved Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Book Name: Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Author: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Year of Publication: 2018 Layout: Imtiaz Ali Ansari Publisher: Culture and Tourism Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi Printer: New Indus Printing Press Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Price: Rs.400/- ISBN: 978-969-8100-40-2 Can be had from Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities Department Book shop opposite MPA Hostel Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidaytullah Road Culture and Tourism Department, Karachi-74400 Government of Sindh, Karachi Phone 021-99206073 Dedicated to my mother, Sahib Khatoon (1935-1980) Contents Preface and Acknowledgements 7 Publisher’s Note 9 Introduction 11 1 Prehistoric Circular Tombs in Mol 15 Valley, Sindh-Kohistan 2 Megaliths in Karachi 21 3 Human and Environmental Threats to 33 Chaukhandi tombs and Role of Civil Society 4 Jat Culture 41 5 Camel Art 65 6 Role of Holy Shrines and Spiritual Arts 83 in People’s Education about Mahdism 7 Depiction of Imam Mahdi in Sindhi 97 poetry of Sindh 8 Between Marhi and Math: The Temple 115 of Veer Nath at Rato Kot 9 One Deity, Three Temples: A Typology 129 of Sacred Spaces in Hariyar Village, Tharparkar Illustrations 145 Index 189 8 | Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh Archaeology, Art and Religion in Sindh | 7 book could not have been possible without the help of many close acquaintances. First of all, I am indebted to Mr. Abdul Hamid Akhund of Endowment Fund Trust for Preservation of the Heritage who provided timely financial support to restore and conduct research on Preface and Acknowledgements megaliths of Thohar Kanarao. -

Handbook on Sikhs for the Use of Regimental Officers

CBN BRNCH GenColl — \ i (t / 4 # HANDBOOK ON SIKHS FOR THE USE OF l$egt mental t^ffteeta BJ?C ^ Captain R?W?TALCON it 4th Sikh Infantry, Punjab Frontier Force (Lately Officiating District Recruiting Officer, Sikh District.) 2111 a b a b a D PRINTED AT THE PIONEER PRESS 1896 HS432. .^S-F3 X. 4 » • ✓ * t J * > * 9 • > * •>> J \ </^r - tc l Sj / DEDICATED TO MY ASSISTANT AND TRUE HELPMATE. ir. m, 3f, PREFACE. IN venturing to offer this book to Regimental Officers I much regret that want of time, (9 months in the Sikh Distiict) did not allow me to tour over all the Sikh tracts and so give me the opportunity of making it as complete and thorough as I could have wished. Sketchy as it is, however, I hope that it may help those Officers not yet acquainted with the Singh, and who are brought into contact with him, to better understand and appreciate that splendid pattein of a native soldier, simple in his religion, worshipping the one God ; broad in his views; free in not observing the prejudices of caste • manly in his warlike creed, in his love of sports and in being a true son of the soil; a buffalo, not quick of understanding, but brave, strong and true. Free use has been made of the following books :— Dr. Trumpp’s translation of the Adi Granth; Sir Lepel Griffin’s Rangit Singh; The Census Reports of 1881 and 1891 ; the Gazetteers of the various Sikh districts (and in¬ formation given me by some of the Deputy Commissioners of those districts); the Panth Parkas; and the Sanskar Bagh, a recent book edited by the Hon’ble Baba Khem Singh, C. -

Doctor of Philosophy

PARTICIPATION OF MUSLIM WOMEN IN THE SOCIO-CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES IN NORTH INDIA DURING THE 19TH CENTURY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY By SHAMIM BANO UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH, INDIA 2015 Dedicated To My Beloved Parents and my Supervisor Tariq Ahmed Dated: 26th October, 2015 Professor of History CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Participation of Muslim Women Socio-Cultural and Educational Activities in North India During 19th Century” is the original work of Ms. Shamim Bano completed under my supervision. The thesis is suitable for submission for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. (Prof. Tariq Ahmed) Supervisor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all I thank Almighty Allah, the most gracious and merciful, who gave me the gift of impression and insights for the compilation of this work. With a sense of utmost gratitude and indebtedness, I consider my pleasant duty to express my sincere thanks to my supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmed, who granted me the privilege of working under his guidance and assigned me the topic “Participation of Muslim Women in the Socio-Cultural and Educational Activities During the 19th Century in North India”. He found time to discuss various difficult aspects of the topic and helped me in arranging the collected data in the present shape. Thus, this research work would hardly have been possible without his learned guidance and careful supervision. I do not know how to adequately express my thanks to him. -

PREFACE This Work on the Sikh Misals Mainly Relates to The

PREFACE This work on the Sikh Misals mainly relates to the eighteenth century which is, undoubtedly, the most eventful period in the Sikh history. It has been done at the instance of Dr Ganda Singh, one of India’s top-ranking historians of his time and the most distinguished specialist of the eighteenth century Punjab history. For decades, there had been nothing nearer his heart than the desire of writing a detailed account of the Sikh Misals. Due to his preoccupation with many contro- versial issues of the Sikh history he kept on postponing this work to a near future. But a day came when the weight of years and failing health refused to permit him to undertake this work. He asked me to do it and magnanimously placed at my disposal his unrivalled life-long collection of Persian manuscripts and other rare books relating to the period. Thus, with the most invaluable source material at my working desk my job became easier. I have always felt incensed at the remarks that the eighteenth century was a dark period of Sikh history. The more I studied this period the more unconvinced I felt about these remarks Having devoted some three decades exclusively to this period I came to the irrefutable conclusion that it is impossible to find a more chivalrous and more glorious period in the history of the world than the eighteenth century Punjab. In the display of marvelous Sikh national character this period is eminently conspicuous. In utter resourcelessness and confronted with the mighty Mughal government and then the greatest military genius of the time in Asia, in the person of Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Sikhs weathered all storms for well-nigh half a century with utmost fighting capacity, overwhelming zeal and determination, unprecedented sacrifice and unshakable faith in their ultimate victory. -

Kapurthala District, No-15 , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 PUNJAB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK No. 15 KAPUR THALA DISTRICT R. L.ANAND Superintendent of Census Operations, Punjab, HarYana, and Union Territory of Chandigarh Published by the Oovernmen~ of Punjab 1967 Price Rs. 18.75 ' ." o ... ..... .. ... PI •H • r.... ~~., .. " " 1('''''''' ••••••( ... " ., " , "" ! '~'\, • / :".: ".._., ,. \' ........ _.,.-.~., 1. .... ( ,.. ~"~:..,.... ~'. : \ .... j ,.". ..... ) '"' . ,J "'" I " '"tt •,. ') ~ > > III III ') II: I- bI ..... III 2 0 '"oJ oJ 2 lII: I I I jj 0 .. @O z • a 0 ;) I- 1/1 Q. 1/1 U a: III )- II: :::I 11.1 ~ 0 0 e t- >:- II: l-'" 0 a iJ f- a: II: e .J 1/1 e II: e 1&1 0 e z :::I :::I II. IIJ z II: 0 0 a a III :::I e U 0 0 a: U 0 e I- UI 0 II: e Z m '"~ II: III Z 0 :::I 1:'" X IIJ '"0 I- e 0 '"U Z I- U It .J'" :::I U .J "IIJ 0 .J a: .J Z e 0 a: e I&. l- e III e 1/1 " l- e I- m LLI III 0 > z III :z: 0 e e a: " ~(.: Y~ a: 'II: U' Q I- :::I CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 A-CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICA nONS The publications relating to Punjaj bear Volume No. XIII, and are bound separately as follows:- General Report Part IV-A RePort on Housing and Establish ments Report on Vital Statistics Part IV-B Tables on Housing and Establish ments Part I-CO) Subsidiary Tables Part V-A Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Trib,.., Part I -CUi) Subsidiary Ta bles Part V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part II-A General Population Ta bles Part VI Village Survey Monographs : 44 in number, each relating to an individual village Part II-B (i) General Economic Tables (Tables Part VII-A Report on Selected Handicrafts B-I to B-IV.