Fandubbing Across Time and Space: from Dubbing 'By Fans for Fans'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Translating' Emotions: Nationalism in Contemporary Greek Cinema

‘Reading’ and ‘Translating’ Emotions: Nationalism in Contemporary Greek Cinema by Sophia Sakellis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Department of Modern Greek and Byzantine Studies The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney October 2016 ABSTRACT This study explores emotions related to nationalism, and their manifestations in contemporary Greek cinema. It also investigates the reasons and mechanisms giving rise to nationalism, and how it is perceived, expressed and ‘translated’ into other cultures. A core focus within the nationalist paradigm is the theme of national identity, with social exclusion ideologies such as racism operating in the background. Two contemporary Greek films have been chosen, which deal with themes of identity, nationalism, xenophobia, anger and fear in different contexts. The study is carried out by drawing on the theories of emotion, language, translation and cinema, to analyse the visual and audio components of the two films and ascertain their translatability to an Australian audience. Both films depict a similar milieu to each other, which is plagued by the lingering nature of all the unresolved political and national issues faced by the Greek nation, in addition to the economic crisis, a severe refugee crisis, and externally imposed policy issues, as well as numerous other social problems stemming from bureaucracy, red tape and widespread state-led corruption, which have resulted in massive rates of unemployment and financial hardship that have befallen a major part of the population. In spite of their topicality, the themes are universal and prevalent in a number of countries to varying degrees, as cultural borders become increasingly integrated, both socially and economically. -

Pobierz Pobierz

Zagadnienia Rodzajów Literackich The Problems of Literary Genres Les problèmes des genres littéraires „Zagadnienia Rodzajów Literackich” — zadanie finansowane w ramach umowy 597/P-DUN/2017 ze środków Ministra Nauki i Szkodnictwa Wyższego przeznaczonych na działalność upowszechniającą naukę. Ł ó d z k i e T o wa r z y s T w o N a u ko w e s o c i e Ta s s c i e nt i a r u m L o d z i e N s i s WYDZIAŁ I SECTIO I Zagadnienia Rodzajów Literackich Tom LX zeszyT 3 (123) Łódź 2017 REDAKTOR NACZELNY/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jarosław Płuciennik REDAKCJA/EDITORS Craig Hamilton, Agnieszka Izdebska, Michał Wróblewski SEKRETARZ/SECRETARY Anna Zatora Pełniący obowiązki sekretarza/acting secretary Michał Rozmysł rada redakcyjna/advisory board Urszula Aszyk-Bangs (Warszawa), Mária Bátorová (Bratislava), Włodzimierz Bolecki (Warszawa), Hans Richard Brittnacher (Berlin), Jacek Fabiszak (Poznań), Margaret H. Freeman (Heath, MA), Grzegorz Gazda (Łódź), Joanna Grądziel-Wójcik (Poznań), Mirosława Hanusiewicz-Lavallee (Lublin), Glyn M. Hambrook (Wolverhampton, UK), Marja Härmänmaa (Helsinki), Magdalena Heydel (Kraków), Yeeyon Im (Gyeongbuk, South Korea), Joanna Jabłkowska (Łódź), Bogumiła Kaniewska (Poznań), Anna Kędra-Kardela (Lublin), Ewa Kraskowska (Poznań), Vladimir Krysinski (Montréal), Erwin H. Leibfried (Giessen), Anna Łebkowska (Kraków), Piotr Michałowski (Szczecin), Danuta Opacka-Walasek (Katowice), Ivo Pospíšil (Brno), Charles Russell (Newark, NJ), Naomi Segal (London), Mark Sokolyanski (Odessa-Lübeck), Dariusz Śnieżko (Szczecin), Reuven Tsur (Jerusalem) redakcja językowa/Language editors Stephen Dewsbury, Craig Hamilton, Reinhard Ibler, Viktoria Majzlan recenzenci w roku 2017/reviewers for 2017 Lista recenzentów zostanie opublikowana w czwartym zeszycie. © Copyright by Łódzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe, Łódź 2017 Printed in Poland Druk czasopisma sfinansowany przez Uniwersytet Łódzki. -

WINGS of HONNEAMISE Oe Ohne) 7 Iy

SBP ee TON ag tatUeasai unproduced sequel to THE WINGS OF HONNEAMISE oe Ohne) 7 iy Sadamoto Yoshiyuki © URU BLUE The faces and names you'll need to know forthis installment of the ANIMERICA Interview with Otaking Toshio Okada. INTERVIEW WITH TOSHIO OKADA, PART FOUR of FOUR In Part Four, the conclusion of the interview, Toshio Okada discusses the dubious ad cam- paign for THE WINGS OF HONNEAMISE, why he wanted Ryuichi Sakamotoforits soundtrack, his conceptfor a sequel and the “shocking truth” behind Hiroyuki Yamaga’‘s! Ryuichi Sakamoto Jo Hisaishi Nausicaa Celebrated composer whoshared the Miyazaki’s musical composer on The heroine of whatis arguably ANIMERICA: There’s something I’ve won- Academy Award with David Byrne mostofhis films, including MY Miyazaki’s most belovedfilm, for the score to THE LAST EMPEROR, NEIGHBOR TOTORO; LAPUTA; NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF dered aboutfor a long time. You know,the Sakamotois well known in both the NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF WIND,Nausicaais the warrior U.S. andJapan for his music, both in WIND; PORCO ROSSOand KIKI’S princess of a people wholive ina ads forthe film had nothing to do with the Yellow Magic Orchestra and solo. DELIVERY SERVICE. Rvorld which has been devadatent a 1 re Ueno, Yuji Nomi an a by ecological disaster. Nausicaa actual film! we composedcai eae pe eventually managesto build a better 7 S under Sakamatne dIcelon, life for her people among the ruins . : la etek prcrely com- throughhernobility, bravery and Okada: [LAUGHS] Toho/Towa wasthe dis- pasetiesOyromaltteats U self-sacrifice.. tributor: of THE WINGS OF HONNEAMISE, “Royal SpaceForce Anthem,” and and they didn’t have any know-how,or theSpace,”“PrototypeplayedC’—ofduringwhichthe march-of-“Out, to sense of strategy to deal with< the film.F They Wonthist ysHedi|thefrouaheiation.ak The latest from Gainaxz handle comedy, and comedy anime—what. -

Cultural Contexts in Understanding Japanese Literature and Cinema

KATARZYNA MARAK Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland POINTS OF CONTACT: CULTURAL CONTEXTS IN UNDERSTANDING JAPANESE LITERATURE AND CINEMA „It rips off The Changeling. If you haven't seen this horror classic with George C. Scott, you should. This film was released in 1979 and has the same elements about the ghost of a young child murdered and thrown into a well. Very similar, only I like The Changeling more because it didn't contain cheap CGI effects like with the black-haired girl and flies buzzing out of a TV screen. The author of Ringu obviously liked The Changeling too.” „The author of Ringu, Koji Suzuki, based his story on a Japanese folk tale. If you would've actually read the book, then you would know, that it's very different from the films. Also, if The Ring sup- posedly ripped off The Changeling, then so did Stir of Echoes, What Lies Beneath, and many other similar films, so quit being so daft.” The above comments come from the Internet Movie Database (imdb.com) message board, and they concern Gore Verbinski’s 2002 film The Ring. Although remakes as such are not the main subject of this paper, the comments quoted above point to a larger, more important matter. The remakes are, however, a good starting point. Remaking a film means, to some extent, translating or remaking the idea or concept into our own cultural background. To work and perform as a successful production, a remake has to describe culturally strange premises by means of cultur- ally familiar elements. Books cannot be remade in the same way that popular films can. -

Birthdays Susan Cole

Volume 29 Number 4 Issue 346 September 2016 A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Kimber Groman (graphic artist) and others August was Worldcon in Kansas City. MidAmericon 2 $25 for 3 days pre con, $30 at the door had a lot going on. There were two Hugo Ceremonies. There spacecoastcomiccon.com were a lot of exhibits and of course 5,000 items on the program. I did a lot of work pre-con and got to see aKansas City at the Animate! Florida same time. The con was great and I need to start working on my September 16-19 report. Port St Lucie Civic Center This month I may checkout some local events. I may try 9221 SE Civiv Center Place to squeeze in a review. Port St Lucie FL As always I am willing to take submissions. Guests: Tony Oliver (Rick Hunter, Robotech) See you next month. Julie Dolan (Star Wars: Rebels) Erica Mendez (Ryoka Matoi, Kill La Kill) Events and many more $55 for 3 days pre con Comic Book Connection animateflorida.com/ September 3-4 Holiday Inn Treasure Comic Con 2300 SR 16 September 16-19 ST Augustine, FL 32084 Greater Fort Lauderdale Convention Center $5 at the door 1950 Eisenhower Blvd, thecomicbookconnection.com Fort Lauderdale, FL 33316 Guests: Space Coast Comic Con Billy West (Phil Fry, Futurama) September 9-11 Kristin Bauer (Maleficient, Once Upon a Space Coast Convention Center Time) 301 Tucker Ln Beverly Elliot(Granny, Once Upon a Time) Cocoa, FL 32926 and many more Guests: Terance Baker (comic artist) $35 for 3 days pre con, $40 at the door Jake Estrada (comic artist) www.treasurecoastcomiccon.com Fusion Con II September 17 Birthdays New Port Richey Recreation & Aquatic Center 6630 Van Buren St Susan Cole - Sept. -

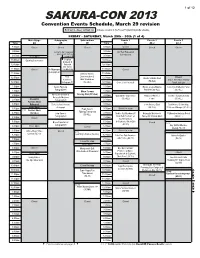

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

Pdf 611.37 K

Socio-Cultural and Technical Issues in Non-Expert Dubbing: A Case Study Christiane Nord1a, Masood Khoshsaligheh2b, Saeed Ameri3b Abstract ARTICLE HISTORY: Advances in computer sciences and the emergence of innovative technologies have entered numerous new Received November 2014 elements of change in translation industry, such as the Received in revised form February 2015 inseparable usage of software programs in audiovisual Accepted February 2015 translation. Initiated by the expanding reality of fandubbing Available online February 2015 in Iran, the present article aimed at illuminating this practice into Persian in the Iranian context to partly address the line of inquiries about fandubbing which still is an uncharted territory on the margins of Translation Studies. Considering the scarce research in this area, the paper aimed to provide data to attract more attention to the notion of fandubbing by KEYWORDS: providing real-world examples from a community with a language of limited diffusion. An exploratory review of a Non-expert dubbing large and diverse sample of openly accessed dubbed Fundubbing products into Persian, ranging from short-formed clips to Fandubbing feature movies, such dubbing practice was further classified Quasi-professional dubbing into fundubbing, fandubbing, and quasi-professional dubbing. User-generated translation Based on the results, the study attempted to describe the cultural aspects and technical features of each type. © 2015 IJSCL. All rights reserved. 1 Professor, Email: [email protected] 2 Assistant Professor, Email: [email protected] (Corresponding Author) Tel: +98-915-501-2669 3 MA Student, Email: [email protected] a University of the Free State, South Africa b Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran 2 Socio-Cultural and Technical Issues in Non-Expert Dubbing: A Case Study 1. -

Apatoons.Pdf

San Diego Sampler #3 Summer 2003 APATOONS logo Mark Evanier Cover Michel Gagné 1 Zyzzybalubah! Contents page Fearless Leader 1 Welcome to APATOONS! Bob Miller 1 The Legacy of APATOONS Jim Korkis 4 Who’s Who in APATOONS APATOONers 16 Suspended Animation Special Edition Jim Korkis 8 Duffell's Got a Brand New Bag: San Diego Comicon Version Greg Duffell 3 “C/FO's 26th Anniversary” Fred Patten 1 “The Gummi Bears Sound Off” Bob Miller 4 Assorted Animated Assessments (The Comic-Con Edition) Andrew Leal 10 A Rabbit! Up Here? Mark Mayerson 11 For All the Little People David Brain 1 The View from the Mousehole Special David Gerstein 2 “Sometimes You Don’t Always Progress in the Right Direction” Dewey McGuire 4 Now Here’s a Special Edition We Hope You’ll REALLY Like! Harry McCracken 21 Postcards from Wackyland: Special San Diego Edition Emru Townsend 2 Ehhh .... Confidentially, Doc - I AM A WABBIT!!!!!!! Keith Scott 5 “Slices of History” Eric O. Costello 3 “Disney Does Something Right for Once” Amid Amidi 1 “A Thought on the Powerpuff Girls Movie” Amid Amidi 1 Kelsey Mann Kelsey Mann 6 “Be Careful What You Wish For” Jim Hill 8 “’We All Make Mistakes’” Jim Hill 2 “Getting Just the Right Voices for Hunchback's Gargoyles …” Jim Hill 7 “Animation vs. Industry Politics” Milton Gray 3 “Our Disappearing Cartoon Heritage” Milton Gray 3 “Bob Clampett Remembered” Milton Gray 7 “Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs: An Appreciation” Milton Gray 4 “Women in Animation” Milton Gray 3 “Men in Animation” Milton Gray 2 “A New Book About Carl Barks” Milton Gray 1 “Finding KO-KO” Ray Pointer 7 “Ten Tips for Surviving in the Animation Biz” Rob Davies 5 Rob Davies’ Credits List Rob Davies 2 “Pitching and Networking at the Big Shows” Rob Davies 9 Originally published in Animation World Magazine, AWN.com, January 2003, pp. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Subtitles and Dubbing: Translation in the TV Series

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Eliška Kratochvílová Subtitles and Dubbing: Translation in the TV Series “The Big Bang Theory” Bachelor‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Ing. Mgr. Jiří Rambousek 2014 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‟s signature Acknowledgement I would like to thank the supervisor of my thesis, Ing. Mgr. Jiří Rambousek, for his valuable advice and guidance. I would also like to thank Mgr. Martin Němec, Ph.D., Kristýna Routnerová, and MartyCZ for providing information necessary for this research. Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Translation in general ................................................................................................... 7 3. History of subtitling and dubbing ............................................................................... 10 3.1. The history of subtitling ....................................................................................... 10 3.2. The history of dubbing ......................................................................................... 12 3.3. Subtitling and dubbing in European countries and the Czech Republic .............. 13 4. Subtitling .................................................................................................................... -

Castle in the Sky Press Kit.P65

CASTLE IN THE SKY This press kit would not have been possible without the assistance, hard work, and dedication of the following individuals. IT Production Coordinator Chris Wallace ................................ [email protected] Design and Layout K Michael S. Johnson ....................... [email protected] Chris Wallace ................................ [email protected] Senior Contributor Ryoko Toyama............................... [email protected] Contributors / Researchers / Editors Jeremy Blackman .......................... [email protected] Shun Chan .................................... [email protected] Marc Hairston ................................ [email protected] Rodney Smith ................................ [email protected] Tom Wilkes .................................... [email protected] Story Synopsis Dana Fong and Chris Wallace Contact Information - Team Ghiblink Team Ghiblink Michael S. Johnson, Project Lead (425) 936-0581 (Work) (425) 867-5189 (Home) [email protected] NFORMATION Contact Information - Buena Vista Home Video Entertainment Buena Vista Home Video Screener List (800) 288-BVHV I [email protected] Team Ghiblink is a group of fans of the works of Studio Ghibli and its directors, including Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and the late Yoshifumi Kondo. Team Ghiblink maintains the Hayao Miyazaki Web at www.nausicaa.net, as well as the Miyazaki Mailing List at [email protected]. This document is a Press Information Kit for the film Castle in the Sky. It is produced by Team Ghiblink in support of this film’s release and is intended for use by patrons and members of the press. Permission is granted to reproduce and distribute this document in whole or in part, provided credit and copyright notices are given. Customized editions of this kit are available by contacting Team Ghiblink at the listed address. RESS The Team Ghiblink and Nausicaa.net logos are copyrighted by Team Ghiblink. -

English and Translation in the European Union

English and Translation in the European Union This book explores the growing tension between multilingualism and mono- lingualism in the European Union in the wake of Brexit, underpinned by the interplay between the rise of English as a lingua franca and the effacement of translations in EU institutions, bodies and agencies. English and Translation in the European Union draws on an interdisciplinary approach, highlighting insights from applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, translation studies, philosophy of language and political theory, while also look- ing at official documents and online resources, most of which are increasingly produced in English and not translated at all – and the ones which are translated into other languages are not labelled as translations. In analysing this data, Alice Leal explores issues around language hierarchy and the growing difficulty in reconciling the EU’s approach to promoting multilingualism while fostering monolingualism in practice through the diffusion of English as a lingua franca, as well as questions around authenticity in the translation process and the bound- aries between source and target texts. The volume also looks ahead to the impli- cations of Brexit for this tension, while proposing potential ways forward, encapsulated in the language turn, the translation turn and the transcultural turn for the EU. Offering unique insights into contemporary debates in the humanities, this book will be of interest to scholars in translation studies, applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, philosophy and political theory. Alice Leal is Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Translation Studies of the Uni- versity of Vienna, Austria. Routledge Advances in Translation and Interpreting Studies Titles in this series include: 63 English and Translation in the European Union Unity and Multiplicity in the Wake of Brexit Alice Leal 64 The (Un)Translatability of Qur’anic Idiomatic Phrasal Verbs A Contrastive Linguistic Study Ali Yunis Aldahesh 65 The Qur’an, Translation and the Media A Narrative Account Ahmed S. -

Graphic Novels Plan

Automatically Yours™ from Baker & Taylor Automatically Yours™ Graphic Novels Plan utomatically YoursTM from Baker & Taylor is a Specialized Collection Program that delivers the latest publications from popular authors right to Ayour door, automatically. Automatically Yours offers a variety of plans to meet your library’s needs including: Popular Adult Fiction Authors, B&T Kids, Spokenword Audio, Popular Book Clubs and Graphic Novels. Our Graphic Novels Plan delivers the latest publications to your library, automatically. Choose the novels that are right for your library and we’ll do the rest. No more placing separate orders, no worrying about title availability - they’ll arrive on time at your library. A new feature of the Automatically Yours program is updated lists of forthcoming titles available on our website, www.btol.com. Click on the Public Tab, then choose Automatic Shipments and Automatically Yours to view the current lists. Sign-up today! Simply fill out the enclosed listing by indicating the number of copies you require, complete the Account Information Form and return them both to Baker & Taylor. It’s that simple! Questions? Call us at 800.775.1200 x2315 or visit www.btol.com Automatically Yours™ from Baker & Taylor Sign up by Vendor/Character, Author or Illustrator. Fill in the quantity you need for each selection, fill out the Account Information Form and we’ll do the rest. It’s that simple! * Vendor/Character Listing: AIT-Planet Lar: ____ Hellboy - Adult Fantagraphics: ____ ALL Titles - Teen ____ Lone Wolf and Cub - Adult ____ ALL Hardcover Titles - Adult ____ O My Goddess - All Ages ____ ALL Paperback Titles - Adult Alternative Comics: ____ Predator - Teen ____ ALL Titles - Adult G.T.