RVW Final Feb 06 21/2/06 12:44 PM Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nus » Indiqué Sur La Pochette, Sont Dis- En Résumé, Je Vous Recommande For- Ponibles En Cliquant Ou Sélectionnant Tement Ce DVD

BEATLES QUÉBEC MAGAZINE PAGE 9 nus » indiqué sur la pochette, sont dis- En résumé, je vous recommande for- ponibles en cliquant ou sélectionnant tement ce DVD. La qualité sonore et au menu, dans les « lobby cards » un visuelle de ce produit est sans égale, des personnages, soit sur John, Paul, compte tenue du produit qui date déjà George ou Ringo ou autre pour qu'ils de plus 42 ans. puissent virer au rouge. De là vous sélectionnez Play et le tour est joué: PROMOTION POUR vous avez les fameux spots de radio. Il LE FILM HELP! y en a 6 en tout répartis sur les 2 DVD. Ces hiddens in menus, appelés en Apple Records a conçu un mini site web pour le film. Vous retrouverez Page d’accueil du site Internet Scène coupée avec Wendy Richard language informatique « easter eggs », sont disponibles dans les deux formats DVD du film HELP!. toutes les informations pertinentes du film ainsi qu’une boutique de marchan- dises « Help! ». www.beatles.com/help UN DRAPEAU HELP! Avec la participation de Ringo Starr, eBay et Capitol Records (USA), un drapeau, mesurant 12 pieds par 18 pieds, à l’effigie du film HELP! , a été Scène coupée avec Wendy Richard offert en encan sur le site eBay. Les Beatles et Apple Records ne ces- Un ensemble d’items accompagnaient seront jamais de nous émerveiller. le fameux drapeau. Le gagnant de l’en- Même après toutes ces années, ils ont can s’est mérité un certificat d’authen- encore le don de nous fasciner. ticité signé par Ringo, un voyage de 5 jours/4 nuits à Londres, une visite au Studio Abbey Road, l’édition deluxe DVD du film Help! , un ensemble de 8 reproductions des « Lobby Cards » de 1965 du film Help! et un CD promo- tionnel (édition limitée). -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

August 1935) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1935 Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935)." , (1935). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/836 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE AUGUST 1935 PAGE 441 Instrumental rr Ensemble Music easy QUARTETS !£=;= THE BRASS CHOIR A COLLECTION FOR BRASS INSTRUMENTS , saptc PUBLISHED FOR ar”!S.""c-.ss;v' mmizm HIM The well ^uiPJ^^at^Jrui^“P-a0[a^ L DAY IN VE JhEODORE pRESSER ^O. DIRECT-MAIL SERVICE ON EVERYTHING IN MUSIC PUBLICATIONS * A Editor JAMES FRANCIS COOKE THE ETUDE Associate Editor EDWARD ELLSWORTH HIPSHER Published Monthly By Music Magazine THEODORE PRESSER CO. 1712 Chestnut Street A monthly journal for teachers, students and all lovers OF music PHILADELPHIA, PENNA. VOL. LIIINo. 8 • AUGUST, 1935 The World of Music Interesting and Important Items Gleaned in a Constant Watch on Happenings and Activities Pertaining to Things Musical Everyw er THE “STABAT NINA HAGERUP GRIEG, widow of MATER” of Dr. -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

View/Download Liner Notes

HUBERT PARRY SONGS OF FAREWELL British Choral Music remarkable for its harmonic warmth and melodic simplicity. Gustav Holst (1874-1934) composed The Evening- 1 The Evening-Watch Op.43 No.1 Gustav Holst [4.59] Watch, subtitled ‘Dialogue between the Body Herbert Howells (1892-1983) composed his Soloists: Matthew Long, Clare Wilkinson and the Soul’ in 1924, and conducted its first memorial anthem Take him, earth, for cherishing 2 A Good-Night Richard Rodney Bennett [2.58] performance at the 1925 Three Choirs Festival in late 1963 as a tribute to the assassinated 3 Take him, earth, for cherishing Herbert Howells [9.02] in Gloucester Cathedral. A setting of Henry President John F Kennedy, an event that had moved Vaughan, it was planned as the first of a series him deeply. The text, translated by Helen Waddell, 4 Funeral Ikos John Tavener [7.41] of motets for unaccompanied double chorus, is from a 4th-century poem by Aurelius Clemens Songs of Farewell Hubert Parry but only one other was composed. ‘The Body’ Prudentius. There is a continual suggestion in 5 My soul, there is a country [3.52] is represented by two solo voices, a tenor and the poem of a move or transition from Earth to 6 I know my soul hath power to know all things [2.04] an alto – singing in a metrically free, senza Paradise, and Howells enacts this by the way 7 Never weather-beaten sail [3.22] misura manner – and ‘The Soul’ by the full his music moves from unison melody to very rich 8 There is an old belief [4.52] choir. -

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994)

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994) Ailie Blunnie Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Master of Literature in Music Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2010 Head of Department: Professor Fiona Palmer Supervisor: Dr Martin O’Leary Contents Acknowledgements i List of Abbreviations iii List of Illustrations iv Preface ix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Part 1: The Early Years (1907–1939): Life and Historical Context 8 Early Education 10 Royal College of Music 11 Octavia Scholarship and Promenade Concert 17 New Beginnings: Leaving College 19 Macnaghten–Lemare Concerts 22 Contracting Tuberculosis 26 Part 2: Music of the Early Years 31 National Trends 34 Maconchy’s Approach to Composition 36 Overview of Works of this Period 40 The Land: Introduction 44 The Land: Movement I: ‘Winter’ 48 The Land: Movement II: ‘Spring’ 52 The Land: Movement III: ‘Summer’ 55 The Land: Movement IV: ‘Autumn’ 57 The Land: Summary 59 The String Quartet in Context 61 Maconchy’s String Quartets of the Period 63 String Quartet No. 1: Introduction 69 String Quartet No. 1: Compositional Procedures 74 String Quartet No. 1: Summary 80 String Quartet No. 2: Introduction 81 String Quartet No. 2: Movement I 83 String Quartet No. 2: Movement II 88 String Quartet No. 2: Movement III 91 String Quartet No. 2: Movement IV 94 Part 2: Summary 97 Chapter 3 Part 1: The Middle Years (1940–1969): Life and Historical Context 100 World War II 101 After the War 104 Accomplishments of this Period 107 Creative Dissatisfaction 113 Part 2: Music of the Middle Years 115 National Trends 117 Overview of Works of this Period 117 The String Quartet in Context 121 Maconchy’s String Quartets of this Period 122 String Quartet No. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ralph Vaughan Williams – Symphony No. 5 in D Major Born October 12, 1872, Gloucestershire, England. Died August 26, 1958, London, England. Symphony No. 5 in D Major Vaughan Williams made his first sketches for this symphony in 1936, began composition in earnest in 1938, completed the work early in 1943, and made minor revisions in 1951. The first performance was given on June 24, 1943, at a Promenade Concert in Royal Albert Hall, with the composer conducting the London Philharmonic. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Vaughan Williams’s Fifth Symphony were given at Orchestra Hall on March 22 and 23, 1945, with Désiré Defauw conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on April 16, 17, and 18, 1987, with Leonard Slatkin conducting. Very early in the twentieth century, Ralph Vaughan Williams began to attract attention as a composer of tuneful songs. But, he eventually declared himself a symphonist, and over the next few years—the time of La mer, Pierrot lunaire, and The Rite of Spring—that tendency alone branded him as old-fashioned. His first significant large-scale work, the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, composed in 1910, is indebted to the music of his sixteenth-century predecessor and to the great English tradition. His entire upbringing was steeped in tradition—he was related both to the pottery Wedgwoods and Charles Darwin. -

Vaughan Williams

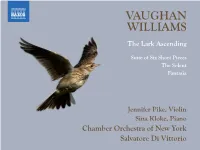

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending Suite of Six Short Pieces The Solent Fantasia Jennifer Pike, Violin Sina Kloke, Piano Chamber Orchestra of New York Salvatore Di Vittorio Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): The Lark Ascending a flinty, tenebrous theme for the soloist is succeeded by an He rises and begins to round, The Solent · Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra · Suite of Six Short Pieces orchestral statement of a chorale-like melody. The rest of He drops the silver chain of sound, the work offers variants upon these initial ideas, which are Of many links without a break, rigorously developed. Various contrasting sections, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake. Vaughan Williams’ earliest compositions, which date from The opening phrase of The Solent held a deep significance including a scherzo-like passage, are heralded by rhetorical 1895, when he left the Royal College of Music, to 1908, for the composer, who returned to it several times throughout statements from the soloist before the coda recalls the For singing till his heaven fills, the year he went to Paris to study with Ravel, reveal a his long creative life. Near the start of A Sea Symphony chorale-like theme in a virtuosic manner. ’Tis love of earth that he instils, young creative artist attempting to establish his own (begun in the same year The Solent was written), it appears Vaughan Williams’ mastery of the piano is evident in And ever winging up and up, personal musical language. He withdrew or destroyed imposingly to the line ‘And on its limitless, heaving breast, the this Fantasia and in the concerto he wrote for the Our valley is his golden cup many works from that period, with the notable exception ships’. -

Directed by Kendall Campbell, Burton Community Church Spring, 1990?

Nov. 12, 1989 - Directed by Kendall Campbell, Burton Community Church Spring, 1990? (no info found) Nov. 18, 1990 – Directed by Jerry McGee, Vashon Lutheran Church Two Madrigals, “Since I First Saw Your Face” & “Musik Dein Ganz Lieblich Kunst” American Folk Songs – “Gentle Lena Clare” & “Misty Morning” “I’ll Sail Upon the Dog Star”, “Whither Must I Wander?” & “Simple Gifts” – G. Koch “Benedictus” by Camille Saint-Saens “Thanks to the Pail”, “The Singer” & “Under the Sea” – M. Ericksen Songs of the Sea – “Just As the Tide Was Flowing” & “High Barbary” April 27, 1991 – Directed by Jerry McGee, LDS Church Concerto Grosso Op. 6 Nr. 1 by G. F. Handel Missa Solemnis in B Flat Major by F.J. Haydn (Kalmus) Dec. 8, 1991 – Directed by Jerry McGee, LDS Church Vesperare Solemnes De Confessore by W.A. Mozart, Kalmus April 12, 1992 – Directed by Jerry McGee, Vashon Island Theater Frostiana, Seven Country Songs, music by Randall Thompson American Spirituals, arr. Harry T. Burleigh Swing Low, arr. G. Alan Smith Wondrous Cool, arr. J. Brahms Phantom of the Opera Choral Medley Dec. 6, 1992 – Directed by Jerry McGee, SJV Church Mass in G by F. Schubert, Schirmer edition Gloria by A. Vivaldi, Kalmus edition April 25, 1993 – Directed by Jerry McGee, McMurray School Come To Me, O My Love by Allan Robert Petker Lavender’s Blue, arr. Gordon Langford The Owl & the Pussycat, arr. Robert Chilcott Give Me a Good Digestion, Lord, arr. Ferguson Turkey In the Straw, arr. Alice Parker Home Is a Special Kind of Feeling by John Rutter, Hinshaw Music Basketball! A Court Jest by Bayne Dobbins Two Chorales from Sørlandet by Bjarne SlØgedal Amazing Grace, arr.