Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

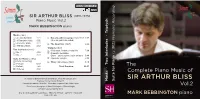

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MARK BEBBINGTON Piano Riptych

SOMMCD 0148 DDD Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MArK BEBBiNGtON piano riptych t Masks (1924) · 1 A Comedy Mask 1:21 bl Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (1932) 2:57 2 A Romantic Mask 3:50 (The old year has ended) Première Recording 3 A Sinister Mask 2:22 bm The Rout Trot (1927) 2:42 4 A Military Mask 2:53 Triptych (1970) Two Interludes (1925) .1912) bn Meditation: Andante tranquillo 7:08 5 c No. 1 4:09 bo ( Dramatic Recitative: 6 nterludes No. 2 3:23 Grave – poco a poco molto animato 5:48 i bp Suite for Piano (c.1912) Capriccio: allegro 5:09 Première Recording bq wo 7 ‛Bliss’ (One-Step) (1923) 3:15 Prelude 5:47 t The 8 Ballade 7:48 Total Duration: 62:11 · 9 Scherzo 3:32 Complete Piano Music of Recorded at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, 3rd & 4th January 2011 Sir Arthur Bliss Steinway Concert Grand Model 'D' Masks Suite for Piano Recording Producer: Siva Oke Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Vol.2 Front Cover photograph of Mark Bebbington: © Rama Knight Design & Layout: Andrew Giles © & 2015 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND MArK BEBBiNGtON piano Made in the EU THE SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF SIR ARTHUR BLISS Vol. 2 Anyone coming new to Bliss’s piano music via these publications might be forgiven for For anyone who has investigated the piano music of Arthur Bliss, the most puzzling thinking that the composer’s contribution to the repertoire was of little significance, aspect is surely that, as a body of work, it remains so little known. -

Recasting Gender

RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Shelley Smith August, 2009 RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN Shelley Smith Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. James Lynn _________________________________ _________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________________ _________________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. THE SHAPING OF A FEMINIST VERNACULAR AND ITS APPLICATION TO 19TH-CENTURY MUSIC ..............................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 The Evolution of Feminism .....................................................................................3 19th-Century Gender Ideologies and Their Encoding in Music ...............................................................................................................8 Soundings of Sex ...................................................................................................19 II. ROBERT & CLARA SCHUMANN: EMBRACING AND DEFYING TRADITION -

Pembelajaran Praktik Biola Melalui Tiga Buku Karya C

PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL: KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI TESIS Oleh SOPIAN LOREN SINAGA NIM. 117037004 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER (S2) PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN SENI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2012 Universitas Sumatera Utara PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL: KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI T E S I S Untuk memperoleh gelar Magister Seni (M.Sn.) dalam Program Studi Magister (S-2) Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni pada Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Sumatera Utara Oleh SOPIAN LOREN SINAGA NIM 117037004 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER (S2) PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN SENI FAKULTAS ILMU BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2013 Universitas Sumatera Utara Judul Tesis : PEMBELAJARAN PRAKTIK BIOLA MELALUI TIGA BUKU KARYA C. PAUL HARFURTH, SUZUKI, DAN ABRSM PADA TINGKATAN PRADASAR DAN DASAR I DI CHANDRA KUSUMA SCHOOL:KAJIAN TERHADAP KELEBIHAN, KELEMAHAN, DAN SOLUSI Nama : Sopian Loren Sinaga Nomor Pokok : 117037004 Program Studi : Magister (S2) Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Menyetujui Komisi Pembimbing, Drs. Muhammad Takari, M.Hum., Ph.D. Dra. Heristina Dewi, M.Pd. NIP. 196512211991031001 NIP. 196605271994032010 Ketua Anggota Program Studi Magister (S-2) Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Dekan, Ketua, Drs. Irwansyah Harahap, M.A. Dr. Syahron Lubis, M.A. NIP 196212211997031001 NIP 195110131976031001 Universitas Sumatera Utara Tanggal lulus: Telah diuji pada Tanggal PANITIA PENGUJI UJIAN TESIS Ketua : Drs. Irwansyah, M.A. (……………………..) Sekretaris : Drs. Torang Naiborhu, M.Hum. (..…..………………..) Anggota I : Drs. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

The Group-Theoretic Description of Musical Pitch Systems

The Group-theoretic Description of Musical Pitch Systems Marcus Pearce [email protected] 1 Introduction Balzano (1980, 1982, 1986a,b) addresses the question of finding an appropriate level for describing the resources of a pitch system (e.g., the 12-fold or some microtonal division of the octave). His motivation for doing so is twofold: “On the one hand, I am interested as a psychologist who is not overly impressed with the progress we have made since Helmholtz in understanding music perception. On the other hand, I am interested as a computer musician who is trying to find ways of using our pow- erful computational tools to extend the musical [domain] of pitch . ” (Balzano, 1986b, p. 297) Since the resources of a pitch system ultimately depend on the pairwise relations between pitches, the question is one of how to conceive of pitch intervals. In contrast to the prevailing approach which de- scribes intervals in terms of frequency ratios, Balzano presents a description of pitch sets as mathematical groups and describes how the resources of any pitch system may be assessed using this description. Thus he is concerned with presenting an algebraic description of pitch systems as a competitive alternative to the existing acoustic description. In these notes, I shall first give a brief description of the ratio based approach (§2) followed by an equally brief exposition of some necessary concepts from the theory of groups (§3). The following three sections concern the description of the 12-fold division of the octave as a group: §4 presents the nature of the group C12; §5 describes three perceptually relevant properties of pitch-sets in C12; and §6 describes three musically relevant isomorphic representations of C12. -

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets Of

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) By © 2017 Matthew Butterfield DMA, University of Kansas, 2017 M.M., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011 B.S., The Pennsylvania State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Dr. Colin Roust Dr. Sarah Frisof Dr. Eric Stomberg Dr. Michelle Hayes Date Defended: 2 May 2017 The dissertation committee for Matthew Butterfield certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Date Approved: 10 May 2017 ii Abstract Léon Goossens’s virtuosity, musicality, and developments in playing the oboe expressively earned him a reputation as one of history’s finest oboists. His artistry and tone inspired British composers in the early twentieth century to consider the oboe a viable solo instrument once again. Goossens became a very popular and influential figure among composers, and many works are dedicated to him. His interest in having new music written for oboe and strings led to several prominent pieces, the earliest among them being the oboe quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927). Bax’s music is strongly influenced by German romanticism and the music of Edward Elgar. This led critics to describe his music as old-fashioned and out of touch, as it was not intellectual enough for critics, nor was it aesthetically pleasing to the masses. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Jazz Harmony Iii

MU 3323 JAZZ HARMONY III Chord Scales US Army Element, School of Music NAB Little Creek, Norfolk, VA 23521-5170 13 Credit Hours Edition Code 8 Edition Date: March 1988 SUBCOURSE INTRODUCTION This subcourse will enable you to identify and construct chord scales. This subcourse will also enable you to apply chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in harmonic progressions. Unless otherwise stated, the masculine gender of singular is used to refer to both men and women. Prerequisites for this course include: Chapter 2, TC 12-41, Basic Music (Fundamental Notation). A knowledge of key signatures. A knowledge of intervals. A knowledge of chord symbols. A knowledge of chord progressions. NOTE: You can take subcourses MU 1300, Scales and Key Signatures; MU 1305, Intervals and Triads; MU 3320, Jazz Harmony I (Chord Symbols/Extensions); and MU 3322, Jazz Harmony II (Chord Progression) to obtain the prerequisite knowledge to complete this subcourse. You can also read TC 12-42, Harmony to obtain knowledge about traditional chord progression. TERMINAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES MU 3323 1 ACTION: You will identify and write scales and modes, identify and write chord scales that correspond to given chord symbols in a harmonic progression, and identify and write chord scales that correspond to triads, extended chords and altered chords. CONDITION: Given the information in this subcourse, STANDARD: To demonstrate competency of this task, you must achieve a minimum of 70% on the subcourse examination. MU 3323 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Subcourse Introduction Administrative Instructions Grading and Certification Instructions L esson 1: Sc ales and Modes P art A O verview P art B M ajor and Minor Scales P art C M odal Scales P art D O ther Scales Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 2: R elating Chord Scales to Basic Four Note Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback L esson 3: R elating Chord Scales to Triads, Extended Chords, and Altered Chords Practical Exercise Answer Key and Feedback Examination MU 3323 3 ADMINISTRATIVE INSTRUCTIONS 1. -

Unit 7 Romantic Era Notes.Pdf

The Romantic Era 1820-1900 1 Historical Themes Science Nationalism Art 2 Science Increased role of science in defining how people saw life Charles Darwin-The Origin of the Species Freud 3 Nationalism Rise of European nationalism Napoleonic ideas created patriotic fervor Many revolutions and attempts at revolutions. Many areas of Europe (especially Italy and Central Europe) struggled to free themselves from foreign control 4 Art Art came to be appreciated for its aesthetic worth Program-music that serves an extra-musical purpose Absolute-music for the sake and beauty of the music itself 5 Musical Context Increased interest in nature and the supernatural The natural world was considered a source of mysterious powers. Romantic composers gravitated toward supernatural texts and stories 6 Listening #1 Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique (4th mvmt) Pg 323-325 CD 5/30 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwCuFaq2L3U 7 The Rise of Program Music Music began to be used to tell stories, or to imply meaning beyond the purely musical. Composers found ways to make their musical ideas represent people, things, and dramatic situations as well as emotional states and even philosophical ideas. 8 Art Forms Close relationship Literature among all the art Shakespeare forms Poe Bronte Composers drew Drama inspiration from other Schiller fine arts Hugo Art Goya Constable Delacroix 9 Nationalism and Exoticism Composers used music as a tool for highlighting national identity. Instrumental composers (such as Bedrich Smetana) made reference to folk music and national images Operatic composers (such as Giuseppe Verdi) set stories with strong patriotic undercurrents. Composers took an interest in the music of various ethnic groups and incorporated it into their own music. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ralph Vaughan Williams – Symphony No. 5 in D Major Born October 12, 1872, Gloucestershire, England. Died August 26, 1958, London, England. Symphony No. 5 in D Major Vaughan Williams made his first sketches for this symphony in 1936, began composition in earnest in 1938, completed the work early in 1943, and made minor revisions in 1951. The first performance was given on June 24, 1943, at a Promenade Concert in Royal Albert Hall, with the composer conducting the London Philharmonic. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Vaughan Williams’s Fifth Symphony were given at Orchestra Hall on March 22 and 23, 1945, with Désiré Defauw conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on April 16, 17, and 18, 1987, with Leonard Slatkin conducting. Very early in the twentieth century, Ralph Vaughan Williams began to attract attention as a composer of tuneful songs. But, he eventually declared himself a symphonist, and over the next few years—the time of La mer, Pierrot lunaire, and The Rite of Spring—that tendency alone branded him as old-fashioned. His first significant large-scale work, the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, composed in 1910, is indebted to the music of his sixteenth-century predecessor and to the great English tradition. His entire upbringing was steeped in tradition—he was related both to the pottery Wedgwoods and Charles Darwin.