Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

The Musical Development of Arnold Bax

THE MUSICAL DEVELOPMENT OF ARNOLD BAX BY R. L. E. FOREMAN ONE of the most enjoyable of musical autobiographies is Arnold Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ml/article/LII/1/59/1326778 by guest on 30 September 2021 Bax's.1 Written in Scotland during the Second War, when he felt himself more or less unable to compose, it brilliantly evokes the composer's life up to the outbreak of the Great War, through a series of closely observed anecdotes. These include portraits of major figures of the time—Elgar, Parry, Mackenzie, Sibelius—making it an important source. Yet curiously enough, though it is the only extended account of any portion of Bax's life that we have, it is not very informative about the composer's musical development, although dealing very amusingly with individual episodes, such as the first performance of 'Christmas Eve on the Mountains'.* Until the majority of Bax's manuscripts were bequeathed to the British Museum by Harriet Cohen,' it was difficult to make even a full catalogue of his music. Now it is possible to trace much of his surviving juvenilia and early work and place it in the framework of the autobiography. In following the evolution of what was a very complex musical style during its developing years it is necessary to take into account both musical and non-musical influences. Bax's early musical influences were Wagner, Elgar, Strauss and Liszt—the latter he referred to as "the master of us all".* Later an important influence was the Russian National School, while other minor influences are noticeable in specific works, including Dvorak (particularly in the first string quartet) and Grieg (in the 'Symphonic Variations'). -

EVELYN BARBIROLLI, Oboe Assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, Harpsichord the SHEPHERD QUARTET

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Rice University EVELYN BARBIROLLI, oboe assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, harpsichord THE SHEPHERD QUARTET Wednesday, October 20, 1976 8:30P.M. Hamman Hall RICE UNIVERSITY Samuel Jones, Dean I SSN 76 .10. 20 SH I & II TA,!JE I PROGRAM Sonata in E-Flat Georg Philipp Telernann Largo (1681 -1767) Vivace Mesto Vivace Sonata in D Minor Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach Allegretto (1732-1795) ~ndante con recitativi Allegro Two songs Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Das Lied der Trennung (1756-1791) _...-1 Vn moto di gioia mi sento (atr. Evelyn Rothwell) 71 u[J. 0...·'1. {) /llfil.A.C'-!,' l.raMc AI,··~ l.l. ' Les Fifres Jean Fra cois Da leu (1682-1738) (arr. Evelyn Rothwell) ' I TAPE II Intermission Quartet Massonneau Allegro madera to (18th Century French) Adagio ' Andante con variazioni Quintet in G Major for Oboe and Strings Arnold Bax Molto mo~erato - Allegro - Molto Moderato (1883-1953) Len to espressivo Allegro giocoso All meml!ers of the audiehce are cordially invited to a reception in the foyer honoring Lady Barbirolli following this evening's concert. EVELYN BARBIROLLI is internationally known as one of the few great living oboe virtuosi, and began her career th1-ough sheer chance by taking up the study qf her instrument at 17 because her school (Downe House, Newbury) needed an oboe player. Within a yenr, she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. Evelyn Rothwell immediately establis71ed her reputation Hu·ough performances and recordings at home and abroad. -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

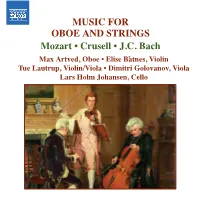

MUSIC for OBOE and STRINGS Mozart • Crusell • J.C. Bach

557361bk USA 26/8/04 7:30 pm Page 4 Max Artved The oboist Max Artved was born in 1965 and joined the Tivoli Boys’ Guard at the age of twelve. In 1980 he entered the Royal Danish Academy of Music, studying with Jørgen Hammergaard, and subsequently with Maurice Bourgue in Paris and Gordon Hunt in London. He made his solo MUSIC FOR début in 1990 and joined the Royal Danish Orchestra in 1991, later the same year becoming principal oboe with the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra. Awards include the Jacob Gade Scholarship, the Gladsaxe Music Prize and the Music Critics’ Artist Prize. His career has brought solo OBOE AND STRINGS engagements in Scandinavia and throughout Europe, and he has contributed to recordings released by dacapo and by Naxos Mozart • Crusell • J.C. Bach Elise Båtnes The violinist Elise Båtnes was appointed leader of the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra in 2002. She has appeared as a soloist, particularly throughout Scandinavia, and was leader of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra. She has been a Max Artved, Oboe • Elise Båtnes, Violin member of the Vertavo Quartet, and has served as artistic director of the Bergen Chamber Ensemble. Tue Lautrup, Violin/Viola • Dimitri Golovanov, Viola Dimitri Golovanov Dimitri Golovanov is a native of St Petersburg, where he studied at the Conservatory, before emigrating from the Soviet Union. He has served as principal violist in the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra since 1994. Lars Holm Johansen, Cello Lars Holm Johansen Lars Holm Johansen was principal cellist in the Royal Danish Orchestra until August 2002, and is well known for his collaboration in chamber music and as a co-founder of the Copenhagen Trio. -

SIR ARTHUR BLISS (1891 - 1975) 1 Mêlée Fantasque (1921 Rev

SRCD.225 STEREO ADD BlissCONDUCTSBliss SIR ARTHUR BLISS (1891 - 1975) 1 Mêlée Fantasque (1921 rev. 1937 & 1965) (13’06”) Mêlée Fantasque 2 Rout for Orchestra and Soprano (1920) (7’24”) Rout Adam Zero - Suite (1946) Adam Zero (Excerpts) 3 II Dance of Spring (2’49”) 4 IV Bridal Ceremony (2’17”) Hymn to Apollo 5 V Dance of Summer (3’48”) Serenade 6 Hymn to Apollo (1928 rev. 1965) (10’23”) (conducted by Brian Priestman) Serenade for Orchestra and Baritone (1929)† (25’52”) The World is charged 7 I Overture: The Serenader (8’30”) with the grandeur of God 8 II ‘Fair is my Love’ (4’52”) (conducted by Philip Ledger) 9 III Idyll (7’24”) 10 IV ‘Tune on my Pipe the praises of my Love’ (5’06”) London Symphony Orchestra The World is charged with the grandeur of God (1969)* (13’31”) LSO Wind and Brass Ensemble 11 I ‘The World is charged with the grandeur of God’ (5’22”) Ambrosian Singers 12 II ‘I have desired to go’ (3’18”) Rae Woodland 13 III ‘Look at the Stars’ (4’51”) John Shirley-Quirk (79’13”) Rae Woodland, soprano • John Shirley-Quirk, baritone London Symphony Orchestra LSO Wind and Brass Ensemble • Ambrosian Singers* Sir Arthur Bliss • Brian Priestman† • Philip Ledger* The above individual timings will normally each include two pauses. One before the beginning of each movement or work, and one after the end. ൿ 1971 The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. This compilation and the digital remastering ൿ 1992 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. -

Concerto for Violin and String Orchestra

BRITISH VIOLIN CONCERTOS Paul Patterson Kenneth Leighton Gordon Jacob Clare Howick, Violin BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Grant Llewellyn Paul Patterson (b. 1947): Violin Concerto No. 2 (‘Serenade’) (2013) 21:57 British Violin Concertos For Clare Howick Paul Patterson • Kenneth Leighton • Gordon Jacob 1 I. Toccata – 5:15 Contrary to opulent violin concertos conceived on a grand movement is virtually monothematic in its close allegiance 2 II. Barcarolle – 8:45 scale by Edward Elgar and William Walton, for example, to a haunting and wistful refrain, which is constantly the three British violin concertos featured here adopt a recast in fresh and varied guises. Once again, the harp 3 III. Valse-Scherzo 7:57 more concise approach to the genre using chamber comes to the fore as the music dies away. forces. Though not shunning the time-honoured elements Full orchestral forces are deployed in the sparkling Kenneth Leighton (1929–1988): of bravura display anticipated in concertante works, they Allegro finale. After a short introduction presenting Concerto for Violin and Small Orchestra, Op. 12 (1952) 24:10 cast the solo violinist as first among equals, engaging in tantalising wisps of thematic material, the solo violin has a To Frederick Grinke telling dialogues with a responsive ensemble, rather than brilliant cadenza. This forms a roguishly extended as an individual pitted against the mob. preamble to a lively Valse-Scherzo whose sly harmonic 4 I. Allegro con brio, molto ritmico 7:49 Born in Chesterfield on 15 June 1947, Paul Patterson shifts and intoxicating melodic sweep rounds the concerto 5 II. Intermezzo – Moderato con moto, sempre dolce 5:58 studied composition with Richard Stoker at the Royal off in exuberantly urbane style. -

093-Britten-And-Bliss-Booklet.Pdf

Britten & Bliss Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) 1 Phantasy Quartet, Op. 2 (1932) (13:16) Arthur Bliss (1891–1975) Quintet for Oboe and String Quartet (1927) (22:35) 2 I. Assai sostenuto (8:09) 3 II. Andante con moto (8:40) 4 III. Vivace (5:38) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit foundation devoted to promot- ing the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation’s activities are sup- Britten: String Quartet No. 3, Op. 94 (1975) (25:58) ported in part by contributions and grants from individuals, foundations, corporations, and government agencies including 5 the Alphawood Foundation, Irving Harris Foundation, Kirkland & Ellis Foundation, NIB Foundation, Negaunee Foundation, I. Duets: With moderate movement (5:28) Sage Foundation, Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs (CityArts III Grant), and the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. 6 II. Ostinato: Very fast (3:19) Contributions to The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation may be made at www.cedillerecords.org or by calling 773-989-2515. 7 III. Solo: Very calm (4:40) Producer James Ginsburg 8 IV. Burlesque: Fast–con fuoco (2:14) Engineer Bill Maylone 9 V. Recitative and Passacaglia (La Serenissima) (10:02) Graphic Design Melanie Germond 24 Cover Photo Venice, Italy ca. 1950 by Ferruccio Leiss, © Alinari Archives/CORBIS Vermeer Quartet Recorded October 3 (Bliss) & 4 (Britten Phantasy Quartet), 2005 and April 25–26, 2006 (Britten Quartet No. 3) at WFMT-Chicago Publishers Alex Klein oboe Britten: ©1934 for the Phantasy Quartet and ©1977 for the 3rd String Quartet. -

NOTES on the MUSIC by Robert M

NOTES ON THE MUSIC by Robert M. Johnstone September 16, 2017 Mediterranean Sir Arnold Bax born in Streatham, Surrey, England, in 1883; died in Cork, Ireland, in 1953 premiere: Queen’s Hall, London, November, 1922 instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons; 4 horns; timpani, percussion, harp; strings duration: 4 minutes Sir Arnold Bax was born to a wealthy English Quaker family in a leafy suburb of south London. He studied composition and piano at the Royal Academy where he was influenced by the music of Wagner, Richard Strauss, and Elgar, then at the height of his late Victorian popularity. As a young man Bax read the poetry of W. B. Yeats and fell in love with things Irish, so much so that many considered him native to the Old Sod. He traveled to Ireland often and much of his early music has Celtic overtones. His Irish idyll ended with the onset of World War I and the 1916 Easter Rebellion in Dublin, although he continued to visit sporadically. His death came in Ireland’s second city, Cork, in 1953, shortly after having composed a coronation march for the young Queen Elizabeth II. After the First World War Bax’s career had taken off, with a host of fresh new works, including seven symphonies, various chamber works, and popular tone poems such as Tintagel and The Garden of Fand. An extended liaison with the concert pianist Harriet Cohen added to his sense of contentment during these years, as did the flowering of a friendship with composer Gustav Holst (see below) that included numerous holidays together.