PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mass in G Minor

MASS IN G MINOR VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: string of works broadly appropriate to worship MASS IN G MINOR appeared in quick succession (more than half Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) of the music recorded here emerged during this Vaughan Williams wrote of music as a means of period). Some pieces were commissioned for Mass in G Minor ‘stretching out to the ultimate realities through specific events, or were inspired by particular 1 Kyrie [4.42] the medium of beauty’, enabling an experience performers. But the role of the War in prompting the intensified devotional fervour 2 Gloria in excelsis [4.18] of transcendence both for creator and receiver. Yet – even at its most personal and remote, apparent in many of the works he composed 3 Credo [6.53] as often on this disc – his church music also in its wake should not be overlooked. As a 4 Sanctus – Osanna I – Benedictus – Osanna II [5.21] stands as a public testament to his belief wagon orderly, one of Vaughan Williams’s more 5 Agnus Dei [4.41] in the role of art within the earthly harrowing duties was the recovery of bodies realm of a community’s everyday life. He wounded in battle. Ursula Vaughan Williams, 6 Te Deum in G [7.44] embraced the church as a place in which a his second wife and biographer, wrote that 7 O vos omnes [5.59] broad populace might regularly encounter a such work ‘gave Ralph vivid awareness of 8 Antiphon (from Five Mystical Songs) [3.15] shared cultural heritage, participating actively, how men died’. -

The Development of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Music Department Honors Papers Music Department 1-1-2011 The evelopmeD nt of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams Currie Huntington Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp Recommended Citation Huntington, Currie, "The eD velopment of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams" (2011). Music Department Honors Papers. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp/2 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH CHORAL STYLE IN TWO EARLY WORKS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS An Honors Thesis presented by Currie Huntington to the Department of Music at Connecticut College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field and for the Concentration in Historical Musicology Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 5th, 2011 ABSTRACT The late 19th century was a time when England was seen from the outside as musically unoriginal. The music community was active, certainly, but no English composer since Handel had reached the level of esteem granted the leading continental composers. Leading up to the turn of the 20th century, though, the early stages of a musical renaissance could be seen, with the rise to prominence of Charles Stanford and Hubert Parry, followed by Elgar and Delius. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Vaughan Williams

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending Suite of Six Short Pieces The Solent Fantasia Jennifer Pike, Violin Sina Kloke, Piano Chamber Orchestra of New York Salvatore Di Vittorio Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): The Lark Ascending a flinty, tenebrous theme for the soloist is succeeded by an He rises and begins to round, The Solent · Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra · Suite of Six Short Pieces orchestral statement of a chorale-like melody. The rest of He drops the silver chain of sound, the work offers variants upon these initial ideas, which are Of many links without a break, rigorously developed. Various contrasting sections, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake. Vaughan Williams’ earliest compositions, which date from The opening phrase of The Solent held a deep significance including a scherzo-like passage, are heralded by rhetorical 1895, when he left the Royal College of Music, to 1908, for the composer, who returned to it several times throughout statements from the soloist before the coda recalls the For singing till his heaven fills, the year he went to Paris to study with Ravel, reveal a his long creative life. Near the start of A Sea Symphony chorale-like theme in a virtuosic manner. ’Tis love of earth that he instils, young creative artist attempting to establish his own (begun in the same year The Solent was written), it appears Vaughan Williams’ mastery of the piano is evident in And ever winging up and up, personal musical language. He withdrew or destroyed imposingly to the line ‘And on its limitless, heaving breast, the this Fantasia and in the concerto he wrote for the Our valley is his golden cup many works from that period, with the notable exception ships’. -

Music-Text Relationship in Major Anti-War Masterworks by British Composers

Music-Text Relationship in Major Anti-War Masterworks by British Composers War Requiem by Benjamin Britten and Dona Nobis Pacem, two of the greatest choral-orchestral masterworks of the twentieth century, will be discussed in terms of the relationship between music and text. The focus of the paper discerns how specifically the composers set the music in order to augment or color the text, which is anti-war in nature, making it deeply meaningful and moving for the listener. Dr. William M. Skoog Elizabeth Daughdrill Endowed Fine Arts Chair, Department of Music Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee Department of Music Rhodes College 2000 North Parkway Memphis, TN 38112 8168 Windersville Dr. Bartlett, TN 38133 [email protected] William Skoog, author and presenter In the 1970’s, there was an American popular song with the words: "War,… what is it good for? …absolutely nothing!" The music featured strong rhythmic accents on beats two and four in driving rock patterns; the melody featured a broken line, with something of a violent grunt, depicting those words. The melodic motion was stepwise, almost chant-like in its contour, representing quasi-religious overtones for this text, creating artistic irony. This song was written during the Vietnam War, and became one rallying cry for millions of Americans as an artistic voice against that war. As a musician, one feels acutely compelled to be social-conscious, as art tends to reflect and/or influence society. Music has historically been borne out of a society as a result of conditions surrounding its inception, and has often been a vehicle used to influence society at such times. -

Download Booklet

557590bk Alwyn US 16/5/05 12:31 pm Page 5 James Judd DDD Also available: British Piano Concertos Music Director of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, the British-born conductor James Judd is also the newly 8.557590 appointed Principal Guest Conductor of the Orchestre National de Lille in France. Within a period of seven years as Music Director in New Zealand, he has embarked on an unprecedented number of recordings with the orchestra for the Naxos label, including works by Copland, Bernstein, Vaughan Williams, Gershwin and many others. He has William brought the orchestra to a new level of visibility and international acclaim through appearances at the 2000 Summer Sydney Olympic Arts Festival, the 2003 Auckland International Arts Festival, the Osaka Festival of International Orchestras as well as a specially televised Millennium Concert with Kiri Te Kanawa as soloist. He will lead the ALWYN orchestra on its first ever tour of the major concert halls of Europe culminating in a début appearance at the BBC Proms in the summer of 2005. A graduate of London’s Trinity College of Music, James Judd came to international attention as the Assistant Conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, a post he accepted at the invitation of Lorin Maazel. Piano Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 Four years later he returned to Europe after being appointed Associate Music Director of the European Community Youth Orchestra by Claudio Abbado, an ensemble with which he continues to serve as an honorary Artistic Director. Peter Donohoe, Piano Since that time he has directed the -

British Roots

Thursday 12 December 2019 7.30–9.30pm Barbican LSO SEASON CONCERT BRITISH ROOTS Tippett Concerto for Double String Orchestra Elgar Sea Pictures Interval PAPPANO Vaughan Williams Symphony No 4 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Karen Cargill mezzo-soprano Supported by LSO Friends Broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 6pm Barbican LSO Platforms: Guildhall Artists Vaughan Williams Phantasy Quintet Howells Rhapsodic Quintet Portorius Quartet Welcome News On Our Blog Thank you to our media partners: BBC Radio 3, LSO STRING EXPERIENCE SCHEME BELA BARTÓK AND who broadcast the performance live, and THE MIRACULOUS MANDARIN Classic FM, who have recommended the We are delighted to appoint 14 players to concert to their listeners. We also extend this year’s LSO String Experience cohort. Against a turbulent political background, sincere thanks to the LSO Friends for their Since 1992, the scheme has been enabling Bartók wrote his pantomime-ballet The important support of this concert; we are young string players from London’s music Miraculous Mandarin, which a German delighted to have so many Friends and conservatoires to gain experience playing in music journal reported caused ‘waves of supporters in the audience tonight. rehearsals and concerts with the LSO. They moral outrage’ to ‘engulf the city’ when it will join the Orchestra on stage for concerts premiered in Cologne. Ahead of tonight’s performance, the in the New Year. Guildhall School’s Portorius Quartet gave elcome to this evening’s LSO a recital of music by Vaughan Williams WHAT’S NEXT FOR OUR 2018/19 concert at the Barbican. It is a and Howells on the Barbican stage. -

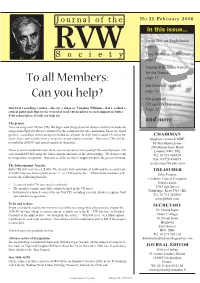

RVW Final Feb 06 21/2/06 12:44 PM Page 1

RVW Final Feb 06 21/2/06 12:44 PM Page 1 Journal of the No.35 February 2006 In this issue... James Day on Englishness page 3 RVWSociety Tony Williams on Whitman page 7 Simona Pakenham writes for the Journal To all Members: page 11 Em Marshall on Holst Can you help? page 14 Six pages of CD and DVD reviews Our f irst r ecording v enture – the rar e songs of Vaughan Williams – has r eached a Page 22 critical point such that we no w need at least 100 members to each support us with a £100 subscription. Could you help us? and more . The project The rare songs will fill two CDs. We begin with Songs from the Operas and this includes ten songs from Hugh the Drover, arranged by the composer for voice and piano. These are world premiere recordings in this arrangement and are all quite lo vely. Our second CD covers the CHAIRMAN Early Years and includes man y songs ne ver previously recorded. These two CDs will be Stephen Connock MBE recorded in 2006-07 and issued separately thereafter. 65 Marathon House 200 Marylebone Road There is much wonderful music here, so rare and yet of such quality!The overall project will London NW1 5PL cost around £25,000 using the f inest singers and state of the art recording. We do not want Tel: 01728 454820 to compromise on quality – thus our need for members’support to drive the project forward. Fax: 01728 454873 [email protected] The Subscriptions’ benefits Both CDs will cost over £25,000. -

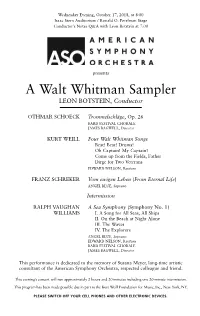

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

A Sea Symphony’ “Richly Drawn Is the Second Symphony – the Romantic, Its Second Movement Anthem Beloved of Millions of Americans

559704 bk Hanson US_559704 bk Hanson US 02/11/2011 14:30 Page 8 Also available in this series: AMERICAN CLASSICS “This is confident, generous, beautifully made music, richly (and sensitively) scored. Tell-tale indications of things to come can be heard in the bonding between strings and descanting horns (the film composer’s favourite tool), the gorgeous ‘old-fashioned’ harmonies radiating from within, and the craggy, wind-swept tuttis (lots of highriding piccolo skirling) so suggestive of that Northern terrain’s stress and strife... Schwarz, and his splendid Seattle orchestra do not short- HOWARD HANSON change us on any of this and they are beautifully, ripely, recorded here.” Gramophone on the original Delos recording Symphony No. 6 • Lumen in Christo 8.559700 Symphony No. 7 ‘A Sea Symphony’ “Richly drawn is the Second Symphony – the Romantic, its second movement anthem beloved of millions of Americans. [Schwarz’s] feeling for long-term growth is possibly the surest of all, leading us from one resolution to the next with an increasing sense of expectation. It’s a Seattle Symphony and Chorale • Gerard Schwarz symphony full of resolutions: of one door opening on to another until we finally step out into the blue beyond. At that point in the finale, Schwarz more than anyone, leaves us in no doubt whatsoever that we have arrived; the emotional release is irresistible.” Gramophone on the original Delos recording 8.559701 “The Symphony No. 3, Hanson’s most extended essay in the form, was written during the late 1930s and is a representative example of the composer at the height of his powers.. -

We Are TEN – in This Issue

RVW No.31 NEW 2004 Final 6/10/04 10:36 Page 1 Journal of the No.31 October 2004 EDITOR Stephen Connock RVW (see address below) Society We are TEN – In this issue... and still growing! G What RVW means to me Testimonials by sixteen The RVW Society celebrated its 10th anniversary this July – just as we signed up our 1000 th new members member to mark a decade of growth and achievement. When John Bishop (still much missed), Robin Barber and I (Stephen Connock) came together to form the Society our aim was to widen from page 4 appreciation of RVW’s music, particularly through recordings of neglected but high quality music. Looking back, we feel proud of what we have achieved. G 49th Parallel World premieres Through our involvement with Richard Hickox, and Chandos, we have stimulated many fine world by Richard Young premiere recordings, including The Poisoned Kiss, A Cotswold Romance, Norfolk Rhapsody No.2, page 14 The Death of Tintagiles and the original version of A London Symphony. Our work on The Poisoned Kiss represents a special contribution as we worked closely with Ursula Vaughan Williams on shaping the libretto for the recording. And what beautiful music there is! G Index to Journals 11-29 Medal of Honour The Trustees sought to mark our Tenth Anniversary in a special way and decided to award an International Medal of Honour to people who have made a remarkable contribution to RVW’s music. The first such Award was given to Richard Hickox during the concert in Gloucester and more . -

Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5-May-2010 I, Mary L Campbell Bailey , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe It is entitled: Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-Century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen Student Signature: Mary L Campbell Bailey This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Mark Ostoich, DMA Mark Ostoich, DMA 6/6/2010 727 Léon Goossens’s Impact on Twentieth-century English Oboe Repertoire: Phantasy Quartet of Benjamin Britten, Concerto for Oboe and Strings of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Sonata for Oboe of York Bowen A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 24 May 2010 by Mary Lindsey Campbell Bailey 592 Catskill Court Grand Junction, CO 81507 [email protected] M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.M., University of South Carolina, 2002 Committee Chair: Mark S. Ostoich, D.M.A. Abstract Léon Goossens (1897–1988) was an English oboist considered responsible for restoring the oboe as a solo instrument. During the Romantic era, the oboe was used mainly as an orchestral instrument, not as the solo instrument it had been in the Baroque and Classical eras. A lack of virtuoso oboists and compositions by major composers helped prolong this status. Goossens became the first English oboist to make a career as a full-time soloist and commissioned many British composers to write works for him.