'Englishness' in the Quartets of Britten, Tippett, and Vaughan Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marion Scott Gleichzeitig Engagierte Sich Marion M

Scott, Marion Marion Scott Gleichzeitig engagierte sich Marion M. Scott musikpoliti- sch in zahlreichen Verbänden und Organisationen, dar- * 16. Juli 1877 in London, England unter die Royal Musical Association, die Royal Philhar- † 24. Dezember 1953 in London, England monic Society und der Forum Club. Eines ihrer Lebens- werke war die Gründung der „Society of Women Musici- Violinistin, Kammermusikerin, Konzertmeisterin, ans“, die sie ab 1911 gemeinsam mit der Sängerin Gertru- Komponistin, Musikwissenschaftlerin, Musikkritikerin, de Eaton und der Komponistin Katharine Eggar aufbau- Förderin (ideell), Musikjournalistin, te – mit eigenem Chor und Orchester, einer Bibliothek (Musik-)Herausgeberin, Konzertorganisatorin, sowie Konzert- und Vortragsreihen. Die Organisation un- Musikpolitikerin, Gründerin und zeitweise Präsidentin terstützte Musikerinnen im britischen Musikleben, führ- der Society of Women Musicians, Schriftstellerin te die Werke von Komponistinnen auf und bemühte sich u. a. darum, die Aufnahme von Musikerinnen in profes- „Unstinted service in the cause of music was the keynote sionelle Orchester zu ermöglichen. Die „Society of Wo- of her life. Countless musicians owe an incalculable debt men Musicians“ blieb bis 1972 bestehen. of gratitude to the fragile little woman who lent them sympathetic and practical aid in their struggles and re- Ab den 1920er-Jahren wandte sich Marion M. Scott dem joiced whole-heartedly in their successes. As a friend she Schreiben über Musik zu. Sie arbeitete als Musikkritike- is irreplaceable.” („Uneingeschränkte Hingabe an die Ar- rin u. a. für die „Musical Times“ und verstärkte mit Arti- beit um der Sache der Musik willen, war der Grundton ih- keln über die Geschichte des Violinspiels, über Auffüh- res Lebens. Unzählige Musiker empfinden der kleinen rungspraxis und Violinliteratur sowie über zeitgenössi- zerbrechlichen Frau gegenüber eine unendliche Dankbar- sche Komponistinnen und Komponisten ihre musikwis- keit, die ihre Arbeit verständnisvoll und tatkräftig unter- senschaftlichen Tätigkeiten. -

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

Guitar Syllabus

TheThe LLeinsteinsteerr SScchoolhool ooff MusMusiicc && DDrramama Established 1904 Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus Contents The Leinster School of Music & Drama ____________________________ 2 General Information & Examination Regulations ____________________ 4 Grade 1 ____________________________________________________ 6 Grade 2 ____________________________________________________ 9 Grade 3 ____________________________________________________ 12 Grade 4 ____________________________________________________ 15 Grade 5 ____________________________________________________ 19 Grade 6 ____________________________________________________ 23 Grade 7 ____________________________________________________ 27 Grade 8 ____________________________________________________ 33 Junior & Senior Repertoire Recital Programmes ________________________ 35 Performance Certificate __________________________________________ 36 1 The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus TheThe LeinsterLeinster SchoolSchool ofof MusicMusic && DraDrammaa Established 1904 "She beckoned to him with her finger like one preparing a certificate in pianoforte... at the Leinster School of Music." Samuel Beckett Established in 1904 The Leinster School of Music & Drama is now celebrating its centenary year. Its long-standing tradition both as a centre for learning and examining is stronger than ever. TUITION Expert individual tuition is offered in a variety of subjects: • Singing and -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

The Only Ones Free Encyclopedia

FREE THE ONLY ONES PDF Carola Dibbell | 344 pages | 10 Mar 2015 | Two Dollar Radio | 9781937512279 | English | Canada The Only Ones - Wikipedia More Images. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Artist. The Only Ones were an influential British rock and roll band in The Only Ones late s who were associated with punk rock, yet straddled the musical territory in between punk, power pop and hard rock, with noticeable influences from psychedelia. They are best known for the song " Another Girl, Another Planet ". Viewing All The Only Ones. Data Quality Correct. Show 25 50 Refresh. Reviews Add Review. Artists I The Only Ones seen live by lancashirearab. Artists in My LP Collection by sillypenta. Master Release - [Help] Release Notes: optional. Submission Notes: optional. Save Cancel. Contained Releases:. The Only Ones Album 20 versions. Sell This Version. Even Serpents Shine Album 15 versions. Baby's Got A Gun Album 24 versions. Remains Comp, EP 6 versions. Closer Records. Live Album 8 versions. Mau Mau Records. The Peel Sessions Album Album 8 versions. Strange Fruit. The Big Sleep Album 5 versions. Jungle Records. Windsong International. Live In Chicago Album 2 versions. Alona's Dream RecordsRegressive Films. Lovers Of Today 2 versions. Vengeance Records 2. Another Girl, Another Planet Single 5 versions. You've Got To Pay Single 3 versions. Fools Single 5 versions. Trouble In The World The Only Ones 8 versions. Special View Comp, Album 11 versions. Alone In The Night Comp 2 versions. The The Only Ones Story Comp 5 versions. ColumbiaColumbia. Hux Records. -

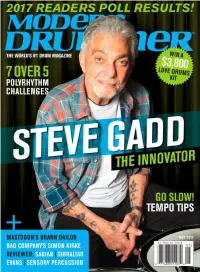

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Download || Editorial Board || Submission Guidelines || Current Issue || Recent Issues || Links & Books

Genders OnLine Journal - "I Want It That Way": Teenybopper Music and the Girling of Boy Bands 1/16/12 11:22 PM Genders 35 2002 Copyright ©2002 Ann Kibbey. "I Want It That Way" Back to: Teenybopper Music and the Girling of Boy Bands by GAYLE WALD You are my fire The one desire Believe when I say I want it that way. - Backstreet Boys, "I Want It That Way" [1] Among recent trends in youth music culture, perhaps none has been so widely reviled as the rise of a new generation of manufactured "teenybopper" pop acts. Since the late 1990s, the phenomenal visibility and commercial success of performers such as Britney Spears, the Backstreet Boys, and 'N Sync has inspired anxious public hand-wringing about the shallowness of youth culture, the triumph of commerce over art, and the sacrifice of "depth" to surface and image. By May 2000, so ubiquitous were the jeremiads against teenybopper pop performers and their fans that Pulse, the glossy in-house magazine of Tower Records, would see fit to mock the popularity of Spears and 'N Sync even as it dutifully promoted their newest releases. Featuring a cover photo of a trio of differently outfitted "Britney" dolls alongside a headline reading "Sells Like Teen Spirit"--a pun on the title of the breakthrough megahit ("Smells Like Teen Spirit") by the defunct rock band Nirvana--Pulse coyly plotted the trajectory of a decade's-long decrescendo in popular music: from the promise of grunge, extinguished with the 1994 suicide of Nirvana lead singer Kurt Cobain, to the ascendancy of girl and boy performers with their own look-alike action figures. -

Mass in G Minor

MASS IN G MINOR VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: string of works broadly appropriate to worship MASS IN G MINOR appeared in quick succession (more than half Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) of the music recorded here emerged during this Vaughan Williams wrote of music as a means of period). Some pieces were commissioned for Mass in G Minor ‘stretching out to the ultimate realities through specific events, or were inspired by particular 1 Kyrie [4.42] the medium of beauty’, enabling an experience performers. But the role of the War in prompting the intensified devotional fervour 2 Gloria in excelsis [4.18] of transcendence both for creator and receiver. Yet – even at its most personal and remote, apparent in many of the works he composed 3 Credo [6.53] as often on this disc – his church music also in its wake should not be overlooked. As a 4 Sanctus – Osanna I – Benedictus – Osanna II [5.21] stands as a public testament to his belief wagon orderly, one of Vaughan Williams’s more 5 Agnus Dei [4.41] in the role of art within the earthly harrowing duties was the recovery of bodies realm of a community’s everyday life. He wounded in battle. Ursula Vaughan Williams, 6 Te Deum in G [7.44] embraced the church as a place in which a his second wife and biographer, wrote that 7 O vos omnes [5.59] broad populace might regularly encounter a such work ‘gave Ralph vivid awareness of 8 Antiphon (from Five Mystical Songs) [3.15] shared cultural heritage, participating actively, how men died’. -

Vol. 17, No. 4 April 2012

Journal April 2012 Vol.17, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2012 Vol. 17, No. 4 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM ‘... unconnected with the schools’ – Edward Elgar and Arthur Sullivan 4 Meinhard Saremba Vice-Presidents The Empire Bites Back: Reflections on Elgar’s Imperial Masque of 1912 24 Ian Parrott Andrew Neill Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Diana McVeagh ‘... you are on the Golden Stair’: Elgar and Elizabeth Lynn Linton 42 Michael Kennedy, CBE Martin Bird Michael Pope Book reviews 48 Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Lewis Foreman, Carl Newton, Richard Wiley Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 52 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Julian Rushton Donald Hunt, OBE DVD reviews 54 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE CD reviews 55 Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley Letters 62 Chairman Steven Halls 100 Years Ago 65 Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Arthur Sullivan: specially engraved for Frederick Spark’s and Joseph Bennett’s ‘History of the Leeds Musical Festivals’, (Leeds: Fred. R. Spark & Son, 1892). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. -

The Development of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Music Department Honors Papers Music Department 1-1-2011 The evelopmeD nt of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams Currie Huntington Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp Recommended Citation Huntington, Currie, "The eD velopment of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams" (2011). Music Department Honors Papers. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp/2 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH CHORAL STYLE IN TWO EARLY WORKS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS An Honors Thesis presented by Currie Huntington to the Department of Music at Connecticut College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field and for the Concentration in Historical Musicology Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 5th, 2011 ABSTRACT The late 19th century was a time when England was seen from the outside as musically unoriginal. The music community was active, certainly, but no English composer since Handel had reached the level of esteem granted the leading continental composers. Leading up to the turn of the 20th century, though, the early stages of a musical renaissance could be seen, with the rise to prominence of Charles Stanford and Hubert Parry, followed by Elgar and Delius. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College.