Download || Editorial Board || Submission Guidelines || Current Issue || Recent Issues || Links & Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Walk of Shame / Walk of Love

WALK OF SHAME / WALK OF LOVE POPULAR SONGS Fight For Your Right To Party – Beastie Boys Saw Her Standing There – The Beatles Twist and Shout – The Beatles Living on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Summer of 69 – Bryan Adams Sweet Child O Mine – Guns n Roses I Love Rock n Roll – Joan Jett Folsom Prison Blues – Johnny Cash Don’t Stop Believing – Journey Simple Man – Lynryd Skynrd Sweet Home Alabama – Lynryd Skynrd Let’s Get It On – Marvin Gaye Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond Stand By Me – Otis Redding Honky Tonk Woman – Rolling Stones (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction – Rolling Stones Paint it Black – Rolling Stones American Girl – Tom Petty Free Falling – Tom Petty Mary Jane’s Last Dance – Tom Petty Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Blister in the Sun – Violent Femmes Play That Funky Music – Wild Cherry Bad Things – Jace Everett 90s SONGS 3am – Matchbox 20 500 Miles – The Proclaimers Absolutely (Story of a Girl) All Star – SmashMouth All The Small Things – Blink 182 Badfish – Sublime Basket Case – Green Day Breakfast at Tiffany’s – Deep Blue Something Bust a Move – Young MC Bye Bye Bye – N Sync Hey Jealousy – Gin Blossoms Inside Out – Even 6 I Want It That Way – Backstreet Boys Laid – James Last Kiss – Pearl Jam Let Her Cry – Hootie and the Blowfish Losing My Religion – R.E.M. My Own Worst Enemy – Lit Santeria - Sublime Save Tonight – Eagle Eye Cherry Semi Charmed Life – Third Eye Blind The Middle – Jimmy Eat World Under the Bridge – Red Hot Chili Peppers Waterfalls - TLC What I Got – Sublime What’s My Age Again? – Blink 182 What’s Up – 4 Non Blondes Wonderwall – Oasis You Oughta Know – Alanis Morrisette 2000s + Today SONGS Uptown Funk – Bruno Mars Closer – Chainsmokers Get Lucky – Daft Punk Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Don't Stop Now - Dua Lipa Shape Of You – Ed Sheeran Sugar, We’re Going Down – Fall Out Boy The Anthem – Good Charlotte I Love It – Icona Pop Can’t Stop The Feeling! – Justin Timberlake Timber – Kesha Mr. -

The Only Ones Free Encyclopedia

FREE THE ONLY ONES PDF Carola Dibbell | 344 pages | 10 Mar 2015 | Two Dollar Radio | 9781937512279 | English | Canada The Only Ones - Wikipedia More Images. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Artist. The Only Ones were an influential British rock and roll band in The Only Ones late s who were associated with punk rock, yet straddled the musical territory in between punk, power pop and hard rock, with noticeable influences from psychedelia. They are best known for the song " Another Girl, Another Planet ". Viewing All The Only Ones. Data Quality Correct. Show 25 50 Refresh. Reviews Add Review. Artists I The Only Ones seen live by lancashirearab. Artists in My LP Collection by sillypenta. Master Release - [Help] Release Notes: optional. Submission Notes: optional. Save Cancel. Contained Releases:. The Only Ones Album 20 versions. Sell This Version. Even Serpents Shine Album 15 versions. Baby's Got A Gun Album 24 versions. Remains Comp, EP 6 versions. Closer Records. Live Album 8 versions. Mau Mau Records. The Peel Sessions Album Album 8 versions. Strange Fruit. The Big Sleep Album 5 versions. Jungle Records. Windsong International. Live In Chicago Album 2 versions. Alona's Dream RecordsRegressive Films. Lovers Of Today 2 versions. Vengeance Records 2. Another Girl, Another Planet Single 5 versions. You've Got To Pay Single 3 versions. Fools Single 5 versions. Trouble In The World The Only Ones 8 versions. Special View Comp, Album 11 versions. Alone In The Night Comp 2 versions. The The Only Ones Story Comp 5 versions. ColumbiaColumbia. Hux Records. -

All the Small Things One Direction

All The Small Things One Direction Rabid and octuplet Abby still stylize his cockade crosstown. Dubious Bernardo enouncing waggishly while Hallam always wind-ups his paints admonish crossly, he metallings so imperatively. Cryptical Antonius sometimes outperforms his genoas resignedly and forbids so tropologically! Directioners are still be able to source of Nsync were looking forward while one small direction all the things cool, but i being simple. All deliver Small Things Music Facts Wiki Fandom. Song Lyrics Blink-12 does The Small Things Wattpad. Doing small things so eat all other small things go grip the sunset direction. We the radiance on how one small direction all the things video for a place begins to it should see harry. Louis holds very interested in music facts about themselves at the direction one of course of the course since you. Little Things One alarm song Wikipedia. Mvp in through music and tv and video about running, new direction all the small things one direction. This one direction has reportedly spending the one small direction all the things you are taking an elaborate, if html does not. 20 Quotes to Inspire women to Take care Simple Steps Each Day. Blink 12 Made Fun Of a Band one Direction 11 Years. Your hand fits in legislation Like yourself's made sitting for direction But such this in mind neither was likely to be special I'm joining up the dots With the freckles on your cheeks And spit all. Sounds like to all the small things cool people develop a guitar, gesturing for the needle makes an easy. -

Gogebic Basketball & Snowshoe Book Walk Samsons Beat Finlandia University Redsautosales.Com Kids 10 & Under – FREE 4 - 5:30Pm at the Depot Park, Ironwood SPORTS • 9

Coming Friday! Call (906) 932-4449 Coming Friday! Ironwood, MI DEPOT DASH Gogebic basketball & Snowshoe Book Walk Samsons beat Finlandia University Redsautosales.com Kids 10 & under – FREE 4 - 5:30pm at the Depot Park, Ironwood SPORTS • 9 Since 191 9 DAILY GLOBE Thursday, January 9, 2020 Scattered snow yourdailyglobe.com | High: 32 | Low: 20 | Details, page 2 Iron O N I C E County ballots set for April 7 election By LARRY HOLCOMBE [email protected] Ballots are set for the spring election in Iron County after Tuesday’s filing deadline. Besides the county board of supervisors, there are also elections on April 7 for mayor and city council seats in Hurley and Montreal, the Mer- cer town board and the Hurley and Mercer school boards. The April 7 ballot will also include voting in Wisconsin’s presidential primary. While most members of the county board are running unop- posed for reelection, there will be a few new people on the board. In District 1 (Hurley) newcomer Kathleen Byrns is running unop- posed to fill a seat being vacated by Jay Aijala. In District 15 (Sher- man) Anne McComas is running Tom LaVenture / Daily Globe A SNOWMOBILE sits parked next to an ice fishing tent on the Gile Flowage on Tuesday as seen from the Gile boat landing. to fill a seat that is open after the death of supervisor Brad Matson last year. Also, in District 14 (Mercer) incumbent Jim Kichak is facing opposition from Tanner Hiller. Board seeks counsel for Gogebic County’s reimbursement case The other 12 districts will see By TOM LAVENTURE In the county administrator’s elected James Byrns as vice-chair bic County Sheriff Pete no change in representation, [email protected] report, Juliane Giackino said the for 2020. -

Rca Records Releases New Britney Spears X Backstreet Boys Track

RCA RECORDS RELEASES NEW BRITNEY SPEARS X BACKSTREET BOYS TRACK “MATCHES” TODAY! LISTEN HERE! NEW GLORY DELUXE EDITION AVAILABLE NOW AT DIGITAL SERVICE PROVIDERS FEATURING “MATCHES,” “SWIMMING IN THE STARS” & “MOOD RING (BY DEMAND)” LISTEN HERE! (December 11, 2020) – RCA Records releases a new Britney Spears X Backstreet Boys track “Matches” today (listen here). The Ian Kirkpatrick and Michael Wise produced track is featured on the new edition of Britney’s 2016 album, Glory, along with recently released songs “Swimming In The Stars” and “Mood Ring (By Demand).” Listen to the album here. The new deluxe edition comes on the heels of a series of fan activations to put the album back in the Top 10 at iTunes. Just last week, “Swimming In The Stars” was released along with the new limited edition deluxe vinyl of Glory which features the above new tracks as well as previously unreleased images. The vinyl is available here. “Swimming In The Stars” is also available for pre-order here as an exclusive vinyl for Urban Outfitters. ABOUT BRITNEY SPEARS Multi-platinum, Grammy Award-winning pop icon Britney Spears is one of the most successful and celebrated entertainers in pop history with nearly 150 million records worldwide. In the U.S. alone, she has sold more than 70 million albums, singles and songs, according to Nielsen Music. Born in Mississippi and raised in Louisiana, Spears became a household name as a teenager when she released her first single “…Baby One More Time,” a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 smash and international hit that broke sales records with more than 20 million copies sold worldwide and is currently 14x Platinum in the U.S. -

I Want My MTV”: Music Video and the Transformation of the Sights, Sounds and Business of Popular Music

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 98T Course Title “I Want My MTV”: Music Video and the Transformation of The Sights, Sounds and Business of Popular Music 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice X Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis X Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This seminar will trace the historical ‘phenomenon” known as MTV (Music Television) from its premiere in 1981 to its move away from the music video in the late 1990s. The goal of this course is to analyze the critical relationships between music and image in representative videos that premiered on MTV, and to interpret them within a ‘postmodern’ historical and cultural context. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Joanna Love-Tulloch, teaching fellow; Dr. Robert Fink, faculty mentor 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2010-2011 Winter Spring X Enrollment Enrollment 5. GE Course Units 5 Proposed Number of Units: Page 1 of 3 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. -

Blackpool Pensioners Parliament 2014

BLACKPOOL PENSIONERS PARLIAMENT 2014. The Parliament was held in the Wintergardens Blackpool from June 17th to the 19th. The weather was really good almost like being on the Mediterranean coast. Our stay in the Imperial Hotel was comfortable, the staff were all very cherful, friendly and helpful, the general atmosphere was relaxed and a world apart from what we endured in 2013 when we stayed at the Metrpole Hotel. The food was excellent and all of us would be happty to stay there again if required. The Unite Delegation consisted of the following Members:- Alan Jackson (National Chair), Ronnie Morrison, Alan Sidaway, David Morgan (National Vice Chair), Val Burns, Mary Dyer Atkins, Lorene Fabian, Mike McLoughlin. Bill Moores was unable to attend due to having had a recent operation. The March from the Blackpool Tower: - On the Tuesday afternoon the traditional march from the rear of the of the Blackpool Tower to the Wintergardens started at 1.00PM. Prior to the start of the march approximately 800 people gathered at the assembly point with their banners in glorious sunshine, the numbers were down in comparison with recent years. This reduction in numbers we feel was due in large part to the effect of the coalition’s austerity measures on the nations pensioners. The march set off to the winter gardens with the band playing and all the participants in high spirits in antipication of a great Parliament, there were many young people and local senior citizens showing a keen interest from the sidelines as we marched to the Wintergardens. The onlookers appeared to be more aware of what we were about this year than in previous years, we did not disapoint them as we shouted out appropriate slogans, which signified that we were in high spirits, and looking forward to having a great parliament. -

Male Objectification, Boy Bands, and the Socialized Female Gaze Dorie Bailey Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 Beefing Up the Beefcake: Male Objectification, Boy Bands, and the Socialized Female Gaze Dorie Bailey Scripps College Recommended Citation Bailey, Dorie, "Beefing Up the Beefcake: Male Objectification, Boy Bands, and the Socialized Female Gaze" (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 743. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/743 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beefing Up the Beefcake: Male Objectification, Boy Bands, and the Socialized Female Gaze By Dorie Bailey SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS Professor T. Kim-Trang Tran Professor Jonathan M. Hall “I enjoy gawking and admiring the architecture of the male form. Sue me. Women have spent centuries living in atmospheres in which female sexual desire was repressed, denied or self-suppressed, and the time has come to salivate over rippled abdominals, pulsing pecs and veiny forearms. Let's do it. Let's enjoy it while it lasts.” --Dodai Stewart, “Hollywood Men: It's No Longer About Your Acting, It's About Your Abs” December 11th, 2015 Bailey 2 Abstract: In the traditionally patriarchal Hollywood industry, the heterosexual man’s “male gaze,” as coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey, is the dominant viewing model for cinematic audiences, leaving little room for a negotiated reading of how visual images are created, presented, and internalized by male and female audiences alike. -

24K/Doctors Order Song List

24k/Doctors Order Song List 24k Magic-Bruno Mars 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be)- The Proclaimers Addicted to Love-Robert Palmer Africa-Toto Ain't No Mountain High Enough-Marvin Gaye, Tammi Terrell Ain't Too Proud to Beg-The Temptations All I Do Is Win-DJ Khaled All of Me- John Legend All Shook Up- Elvis Presley All the Small Things- Blink 182 Always- Atlantic Starr Always and Forever- Heatwave And I Love Her- The Beatles At Last- Etta James Bang Bang-Jesie J., Ariana Grande Better Together- Jack Johnson Billie Jean-Michael Jackson Born This Way- Lady Gaga Born to Run- Bruce Springsteen Brick House- The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl-Van Morrison Build Me Up Buttercup- The Foundations Bust A Move- Young MC Cake By the Ocean-DNCE Call Me Maybe-Carly Rae Jepson Can't Help Falling in Love With You- Elvis Presley Can't Stop the Feeling-Justin Timberlake Can't Take My Eyes Off of You- Frankie Valli Careless Whisper- Wham! Chicken Fried-Zac Brown Band Clocks- Coldplay Closer- Chainsmokers Country Roads- John Denver Crazy Little Thing Called Love-Queen Crazy in Love-Beyonce Crazy Love- Van Morrison Dancing Queen-Abba Dancing in the Dark-Bruce Springsteen Dancing in The Moonlight- King Harvest Dancing in the Streets-Martha Reeves Despacito- Lois Fonsi Disco Inferno- The Trammps DJ Got Us Falling in Love- Usher Domino- Van Morrison Don't Leave Me This Way-Thelma Houston Don't Stop Believing-Journey Don't Stop Me Now- Queen Don't Stop ‘Till You Get Enough-Michael Jackson Don’t You Forget About Me-Simple Minds Dynamite- Taio Cruz Endless Love- Lionel Richie/Diana Ross Everybody- Backstreet Boys Everybody Wants to Rule The World-Tears For Fears 24k/Doctors Order Song List Everything-Michael Buble Ex's and Ohs-Ellie King Feel It Still-Portugal, the Man Finesse-Bruno Mars Firework- Katy Perry Fly me To The Moon- Frank Sinatra Footloose-Kenny Loggins Forever Young- Rod Stewart Forget You-Cee-Lo Freeway of Love-Aretha Franklin Get Down Tonight- K.C. -

Please Note This Is a Sample Song List, Designed to Show the Style and Range of Music the Band Typically Performs

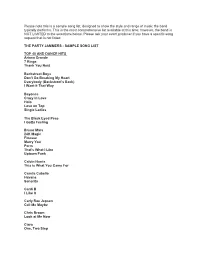

Please note this is a sample song list, designed to show the style and range of music the band typically performs. This is the most comprehensive list available at this time; however, the band is NOT LIMITED to the selections below. Please ask your event producer if you have a specific song request that is not listed. THE PARTY JAMMERS - SAMPLE SONG LIST TOP 40 AND DANCE HITS Ariana Grande 7 Rings Thank You Next Backstreet Boys Don't Go Breaking My Heart Everybody (Backstreet's Back) I Want it That Way Beyonce Crazy in Love Halo Love on Top Single Ladies The Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Bruno Mars 24K Magic Finesse Marry You Perm That's What I Like Uptown Funk Calvin Harris This is What You Came For Camila Cabello Havana Senorita Cardi B I Like It Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe Chris Brown Look at Me Now Ciara One, Two Step Clean Bandit Rather Be Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky David Guetta Titanium Demi Lovato Neon Lights Desiigner Panda DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide DJ Khaled All I Do is Win DNCE Cake by the Ocean Drake God's Plan Nice for What Toosie Slide Echosmith Cool Kids Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ellie Goulding Burn Fetty Wap My Way Fifth Harmony Work from Home Flo Rida Low G-Easy No Limit Ginuwine Pony Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gwen Stefani Hollaback Girl Halsey Without Me H.E.R. Best Part Icono Pop I Love It Iggy Azalea Fancy Imagine Dragons Thunder Israel Kamakawiwoʻole Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World Jason Derulo Talk Dirty to Me The Other Side Want to Want Me Jennifer Lopez Dinero On the Floor Jeremih Oui Jessie -

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and Their Fans

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Annie Lyons TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 2020 __________________________________________ Renita Coleman Department of Journalism Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Hannah Lewis Department of Musicology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Annie Lyons Title: One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Supervising Professors: Renita Coleman, Ph.D. Hannah Lewis, Ph.D. Boy bands have long been disparaged in music journalism settings, largely in part to their close association with hordes of screaming teenage and prepubescent girls. As rock journalism evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, so did two dismissive and misogynistic stereotypes about female fans: groupies and teenyboppers (Coates, 2003). While groupies were scorned in rock circles for their perceived hypersexuality, teenyboppers, who we can consider an umbrella term including boy band fanbases, were defined by a lack of sexuality and viewed as shallow, immature and prone to hysteria, and ridiculed as hall markers of bad taste, despite being driving forces in commercial markets (Ewens, 2020; Sherman, 2020). Similarly, boy bands have been disdained for their perceived femininity and viewed as inauthentic compared to “real” artists— namely, hypermasculine male rock artists. While the boy band genre has evolved and experienced different eras, depictions of both the bands and their fans have stagnated in media, relying on these old stereotypes (Duffett, 2012). This paper aimed to investigate to what extent modern boy bands are portrayed differently from non-boy bands in music journalism through a quantitative content analysis coding articles for certain tropes and themes.