Beethoven's Middle and Late String Quartets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

Michael Brecker Chronology

Michael Brecker Chronology Compiled by David Demsey • 1949/March 29 - Born, Phladelphia, PA; raised in Cheltenham, PA; brother Randy, sister Emily is pianist. Their father was an attorney who was a pianist and jazz enthusiast/fan • ca. 1958 – started studies on alto saxophone and clarinet • 1963 – switched to tenor saxophone in high school • 1966/Summer – attended Ramblerny Summer Music Camp, recorded Ramblerny 66 [First Recording], member of big band led by Phil Woods; band also contained Richie Cole, Roger Rosenberg, Rick Chamberlain, Holly Near. In a touch football game the day before the final concert, quarterback Phil Woods broke Mike’s finger with the winning touchdown pass; he played the concert with taped-up fingers. • 1966/November 11 – attended John Coltrane concert at Temple University; mentioned in numerous sources as a life-changing experience • 1967/June – graduated from Cheltenham High School • 1967-68 – at Indiana University for three semesters[?] • n.d. – First steady gigs r&b keyboard/organist Edwin Birdsong (no known recordings exist of this period) • 1968/March 8-9 – Indiana University Jazz Septet (aka “Mrs. Seamon’s Sound Band”) performs at Notre Dame Jazz Festival; is favored to win, but is disqualified from the finals for playing rock music. • 1968 – Recorded Score with Randy Brecker [1st commercial recording] • 1969 – age 20, moved to New York City • 1969 – appeared on Randy Brecker album Score, his first commercial release • 1970 – co-founder of jazz-rock band Dreams with Randy, trombonist Barry Rogers, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Doug Lubahn. Recorded Dreams. Miles Davis attended some gigs prior to recording Jack Johnson. -

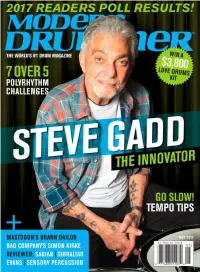

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 9 Number 1 Spring 2019 Article 2 March 2019 Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets Matthew J. Hall Cornell University Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Hall, Matthew J. (2019) "Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn's String Quartets," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 9 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Hall, Matthew. “Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 9.1 (Spring 2019), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2019. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Minor-Mode Sonata-Form Dynamics in Haydn’s String Quartets By Matthew J. Hall Cornell University Abstract The predominance of major-mode works in the repertoire corresponds with the view that minor-mode works are exceptions to a major-mode norm. For example, Charles Rosen’s Sonata Forms, James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy’s Sonata Theory, and William Caplin’s Classical Form all theorize from the perspective of a major-mode default. -

Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz

Classics & Jazz PAID Permit # 79 PRSRT STD PRSRT Late Fall 2020 U.S. Postage Aberdeen, SD Jazz New Naxos Bundle Deal Releases 3 for $30 see page 54 beginning on page 10 more @ more @ HBDirect.com HBDirect.com see page 22 OJC Bundle Deal P.O. Box 309 P.O. 05677 VT Center, Waterbury Address Service Requested 3 for $30 see page 48 Classical 50% Off beginning on page 24 more @ HBDirect.com 1/800/222-6872 www.hbdirect.com Classical New Releases beginning on page 28 more @ HBDirect.com Love Music. HBDirect Classics & Jazz We are pleased to present the HBDirect Late Fall 2020 Late Fall 2020 Classics & Jazz Catalog, with a broad range of offers we’re sure will be of great interest to our customers. Catalog Index Villa-Lobos: The Symphonies / Karabtchevsky; São Paulo SO [6 CDs] In jazz, we’re excited to present another major label as a Heitor Villa-Lobos has been described as ‘the single most significant 4 Classical - Boxed Sets 3 for $30 bundle deal – Original Jazz Classics – as well as a creative figure in 20th-century Brazilian art music.’ The eleven sale on Double Moon, recent Enlightenment boxed sets and 10 Classical - Naxos 3 for $30 Deal! symphonies - the enigmatic Symphony No. 5 has never been found new jazz releases. On the classical side, HBDirect is proud to 18 Classical - DVD & Blu-ray and may not ever have been written - range from the two earliest, be the industry leader when it comes to the comprehensive conceived in a broadly Central European tradition, to the final symphony 20 Classical - Recommendations presentation of new classical releases. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito. -

JAZZ: a Regional Exploration

JAZZ: A Regional Exploration Scott Yanow GREENWOOD PRESS JAZZ A Regional Exploration GREENWOOD GUIDES TO AMERICAN ROOTS MUSIC JAZZ A Regional Exploration Scott Yanow Norm Cohen Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yanow, Scott. Jazz : a regional exploration / Scott Yanow. p. cm. – (Greenwood guides to American roots music, ISSN 1551-0271) Includes bibliographical references and index. Discography: p. ISBN 0-313-32871-4 (alk. paper) 1 . Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. II. Series. ML3508.Y39 2005 781.65'0973—dc22 2004018158 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2005 by Scott Yanow All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2004018158 ISBN: 0-313-32871-4 ISSN: 1551-0271 First published in 2005 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Series Foreword vii Preface xi Chronology xiii Introduction xxiii 1. Sedalia and St. Louis: Ragtime 1 2. New Orleans Jazz 7 3. Chicago: Classic Jazz 15 4. New York: The Classic Jazz and Swing Eras 29 5. Kansas City Swing, the Territory Bands, and the San Francisco Revival 99 6. New York Bebop, Latin, and Cool Jazz 107 7. -

'Englishness' in the Quartets of Britten, Tippett, and Vaughan Williams

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Music Honors Theses Music Department 4-22-2009 The rT ouble with Nationalism: ‘Englishness’ in the Quartets of Britten, Tippett, and Vaughan Williams Sarah Elaine Robinson Trinity University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Sarah Elaine, "The rT ouble with Nationalism: ‘Englishness’ in the Quartets of Britten, Tippett, and Vaughan Williams" (2009). Music Honors Theses. 4. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors/4 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Trouble with Nationalism: ‘Englishness’ in the Quartets of Britten, Tippett, and Vaughan Williams by Sarah Elaine Robinson A thesis submitted to the Department of Music at Trinity University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with departmental honors. 22 April 2009 _________________________________ ________________________________ Thesis Advisor Department Chair _________________________________ Associate Vice-President For Academic Affairs Student Copyright Declaration: the author has selected the following copyright provision: [X ] This thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which allows some noncommercial copying and distribution of the thesis, given proper attribution. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. [ ] This thesis is protected under the provisions of U.S. Code Title 17. -

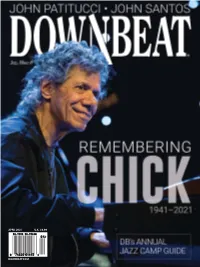

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

FIJAZZ2014.Pdf

BIBLIOTECA PÚBLICA DE ALICANTE MIKE STERN ■ BIOGRAFÍA Mike Stern (* 10 de enero de 1953 en Boston) es un guitarrista estadounidense de jazz que ha trabajado con músicos como Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Jaco Pastorius, Joe Henderson, Jim Hall, Pat Martino, Tom Harrell, Arturo Sandoval, Tiger Okoshi, Michael Brecker, Bob Berg, David Sanborn, Steps Ahead y los Brecker Brothers. Graduado en el Berklee College of Music de Boston, se orientó hacia el jazz desde su formación. Se unió a Blood, Sweat & Tears durante una gira en 1977 y participó en tres de sus discos: In Concert, More than Ever y Brand New Day. Desde entonces ha trabajado con multitud de músicos, destacando su colaboración con Miles Davis desde 1981 hasta 1983. Su primer álbum de estudio, Upside Downside, salió al mercado en 1986 en el sello Atlantic Records, y contó con la colaboración de Jaco Pastorius, David Sanborn y Bob Berg. Su segundo trabajo, titulado Time in Place, fue publicado en 1988 e incluye a Peter Erskine en la batería, Jim Beard en el teclado, Jeff Andrews en el bajo, Don Alias en la percusión y Don Grolnick al órgano. A este disco le siguió Jigsaw un año después, cuando formó un grupo con Berg, Dennis Chambers y Lincoln Goines que duró hasta 1992. En 1993 grabó su mejor disco, Standards (And Other Songs), que le valió para ser proclamado como Mejor guitarrista del año por la revista Guitar Player. Recibió dos nominaciones a los premios Grammy en 1994 y 1996 por los discos Is What It Is y Between the Lines. -

Beethoven - Quartet No 9 in C Major, Op 59 (Rasumovsky) Transcript

Beethoven - Quartet No 9 in C major, Op 59 (Rasumovsky) Transcript Date: Tuesday, 6 May 2008 - 6:00PM BEETHOVEN QUARTET NO 9 IN C MAJOR OP 5 NO 3 Professor Roger Parker I'll start today with an apology and a confession. The apology (which can be brief) is that, in the initial publicity for this series, the quartet today was announced as Beethoven's Op. 95; but some time ago, and for eminently practical reasons, the Badke quartet and I decided to change to the same composer's Op. 59, no. 3. I sincerely hope this inconveniences no-one, and may even please a few of you. The confession (which must be longer) is that I've been having a recurring nightmare about delivering this lecture series. The nightmares of people who appear before the public can be many and various: musicians, for example, have a number of classic ones. In mine, though, it's something quite particular. I arrive at Gresham College in good time for my lecture, armed with a talk crammed full of what dignity and scholarship I can muster. But as I come in, I glance at the notice board and see to my horror that I've got the programme mixed up: the quartet about which I've written my talk is actually due to be played next month; I've prepared the wrong work. What's to be done? The Badke Quartet have no time (and frankly, no inclination) to dash home and grab next month's music; and why should they? I decide I have two choices, neither of them pleasant. -

Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra Sunday / July 18 / 4:00Pm / Venetian Theater

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S.