Season 2013-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

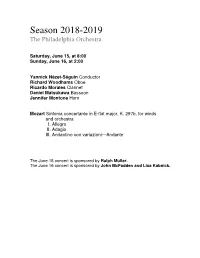

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

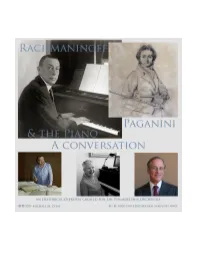

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

(The Bells), Op. 35 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Written: 1913 Movements: Four Style: Romantic Duration: 35 Minutes

Kolokola (The Bells), Op. 35 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Written: 1913 Movements: Four Style: Romantic Duration: 35 minutes Sometimes an anonymous tip pays off. Sergei Rachmaninoff’s friend Mikhail Buknik had a student who seemed particularly excited about something. She had read a Russian translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Bells and felt that it simply had to be set to music. Buknik recounted what happened next: She wrote anonymously to her idol [Rachmaninoff], suggesting that he read the poem and compose it as music. summer passed, and then in the autumn she came back to Moscow for her studies. What had now happened was that she read a newspaper item that Rachmaninoff had composed an outstanding choral symphony based on Poe's Bells and it was soon to be performed. Danilova was mad with joy. Edgar Allen Poe (1809–1849) wrote The Bells a year before he died. It is in four verses, each one highly onomatopoeic (a word sounds like what it means). In it Poe takes the reader on a journey from “the nimbleness of youth to the pain of age.” The Russian poet Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont (1867–1942) translated Poe’s The Bells and inserted lines here and there to reinforce his own interpretation. Rachmaninoff conceived of The Bells as a sort of four-movement “choral-symphony.” The first movement evokes the sound of silver bells on a sleigh, a symbol of birth and youth. Even in this joyous movement, Balmont’s verse has an ominous cloud: “Births and lives beyond all number/Waits a universal slumber—deep and sweet past all compare.” The golden bells in the slow second movement are about marriage. -

Music Company Orchestra |

The Music Company 2019 OUR 45th YEAR 2 3 4 5 ABOUT THE ORCHESTRA The Music Company Orchestra, incor- porated in 1974, is a 60-piece volunteer community orchestra. Its members come from all walks of life and many different backgrounds. Conducted by Dr. Gerald Lanoue, the orchestra plays a wide range of light classical and pops repertoire. The MCO is dedicated to bringing the excitement of live orchestral music to audiences of all ages and economic back- grounds, and enthusiastically plays ven- ues throughout the greater Capital Re- gion, ranging from traditional concert halls to public parks, community events, schools, retirement centers and nursing homes. The MCO performs most concerts free to the public, and also offers schol- arships to music students at three capi- tal district high schools. The MCO is a not-for-profit organiza- tion . 6 Gerald Lanoue Conductor & Music Director Gerald Lanoue, bassoonist and conductor, is a Bennington, Vermont native. He performs throughout the capital region and Vermont with the Middlebury Opera, Pro Musica Orchestra, Hubbard Hall Opera Orchestra, Sage City Symphony and Funf woodwind quintet. He is the Conductor and Music Director of The Music Company Orchestra and Associate Conductor of the Sage City Symphony. After completing studies at the Crane School of Music. Dr. Lanoue received a Masters and Doctorate at the University of Southern California. He studied bassoon with the late Stephen Mayxm, former principal bassoonist of the Metropolitan Opera. Conducting studies were under the batons of Douglas Lowry, former Dean at the Eastman School of Music, and John Barnett, the former associate conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. -

Ravel & Rachmaninoff

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM BY LAURIE SHULMAN, ©2017 2018 Winter Festival America, Inspiring: Ravel & Rachmaninoff ONE-MINUTE NOTES Martinů: Thunderbolt P-47. A World War II American fighter jet was the inspiration for this orchestral scherzo. Martinů pays homage to technology, the machine age and the brave pilots who risked death, flying these bombers to win the war. Ravel: Piano Concerto in G Major. Ravel was enthralled by American jazz, whose influence is apparent in this jazzy concerto. The pristine slow movement concerto evokes Mozart’s spirit in its clarity and elegance. Ravel’s wit sparkles in the finale, proving that he often had a twinkle in his eye. Rachmaninoff: Symphonic Dances. Rachmaninoff’s final orchestral work, a commission from the Philadelphia Orchestra, brings together Russian dance and Eastern European mystery. Listen for the “Dies irae” at the thrilling close. MARTINŮ: Thunderbolt P-47, Scherzo for Orchestra, H. 309 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ Born: December 8, 1890, in Polička, Czechoslovakia Died: August 28, 1959, in Liestal, nr. Basel, Switzerland Composed: 1945 World Premiere: December 19, 1945, in Washington, DC. Hans Kindler conducted the National Symphony. NJSO Premiere: These are the NJSO premiere performances. Duration: 11 minutes Between 1941 and 1945, Republic Aviation built 15,636 P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes. Introduced in November 1942, the aircraft was a bomber equipped with machine guns. British, French and American air forces used them for the last three years of the war. Early in 1945, the Dutch émigré conductor Hans Kindler commissioned Bohuslav Martinů—himself an émigré from Czechoslovakia who had resided in the United States since March 1941—to write a piece for the National Symphony Orchestra. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Commemorative Concert the Suntory Music Award

Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Suntory Foundation for Arts ●Abbreviations picc Piccolo p-p Prepared piano S Soprano fl Flute org Organ Ms Mezzo-soprano A-fl Alto flute cemb Cembalo, Harpsichord A Alto fl.trv Flauto traverso, Baroque flute cimb Cimbalom T Tenor ob Oboe cel Celesta Br Baritone obd’a Oboe d’amore harm Harmonium Bs Bass e.hrn English horn, cor anglais ond.m Ondes Martenot b-sop Boy soprano cl Clarinet acc Accordion F-chor Female chorus B-cl Bass Clarinet E-k Electric Keyboard M-chor Male chorus fg Bassoon, Fagot synth Synthesizer Mix-chor Mixed chorus c.fg Contrabassoon, Contrafagot electro Electro acoustic music C-chor Children chorus rec Recorder mar Marimba n Narrator hrn Horn xylo Xylophone vo Vocal or Voice tp Trumpet vib Vibraphone cond Conductor tb Trombone h-b Handbell orch Orchestra sax Saxophone timp Timpani brass Brass ensemble euph Euphonium perc Percussion wind Wind ensemble tub Tuba hichi Hichiriki b. … Baroque … vn Violin ryu Ryuteki Elec… Electric… va Viola shaku Shakuhachi str. … String … vc Violoncello shino Shinobue ch. … Chamber… cb Contrabass shami Shamisen, Sangen ch-orch Chamber Orchestra viol Violone 17-gen Jushichi-gen-so …ens … Ensemble g Guitar 20-gen Niju-gen-so …tri … Trio hp Harp 25-gen Nijugo-gen-so …qu … Quartet banj Banjo …qt … Quintet mand Mandolin …ins … Instruments p Piano J-ins Japanese instruments ● Titles in italics : Works commissioned by the Suntory Foudation for Arts Commemorative Concert of the Suntory Music Award Awardees and concert details, commissioned works 1974 In Celebration of the 5thAnniversary of Torii Music Award Ⅰ Organ Committee of International Christian University 6 Aug. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Aint Gonna Study War No More / Down by the Riverside

The Danish Peace Academy 1 Holger Terp: Aint gonna study war no more Ain't gonna study war no more By Holger Terp American gospel, workers- and peace song. Author: Text: Unknown, after 1917. Music: John J. Nolan 1902. Alternative titles: “Ain' go'n' to study war no mo'”, “Ain't gonna grieve my Lord no more”, “Ain't Gwine to Study War No More”, “Down by de Ribberside”, “Down by the River”, “Down by the Riverside”, “Going to Pull My War-Clothes” and “Study war no more” A very old spiritual that was originally known as Study War No More. It started out as a song associated with the slaves’ struggle for freedom, but after the American Civil War (1861-65) it became a very high-spirited peace song for people who were fed up with fighting.1 And the folk singer Pete Seeger notes on the record “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and Other Love Songs”, that: "'Down by the Riverside' is, of course, one of the oldest of the Negro spirituals, coming out of the South in the years following the Civil War."2 But is the song as we know it today really as old as it is claimed without any sources? The earliest printed version of “Ain't gonna study war no more” is from 1918; while the notes to the song were published in 1902 as music to a love song by John J. Nolan.3 1 http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/grovemusic/spirituals,_hymns,_gospel_songs.htm 2 Thanks to Ulf Sandberg, Sweden, for the Pete Seeger quote. -

For Release: Tk, 2013

FOR RELEASE: January 23, 2013 SUPPLEMENT CHRISTOPHER ROUSE, The Marie-Josée Kravis COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE WORLD PREMIERE of SYMPHONY NO. 4 at the NY PHIL BIENNIAL New York Premiere of REQUIEM To Open Spring For Music Festival at Carnegie Hall New York Premiere of OBOE CONCERTO with Principal Oboe Liang Wang RAPTURE at Home and on ASIA / WINTER 2014 Tour Rouse To Advise on CONTACT!, the New-Music Series, Including New Partnership with 92nd Street Y ____________________________________ “What I’ve always loved most about the Philharmonic is that they play as though it’s a matter of life or death. The energy, excitement, commitment, and intensity are so exciting and wonderful for a composer. Some of the very best performances I’ve ever had have been by the Philharmonic.” — Christopher Rouse _______________________________________ American composer Christopher Rouse will return in the 2013–14 season to continue his two- year tenure as the Philharmonic’s Marie-Josée Kravis Composer-in-Residence. The second person to hold the Composer-in-Residence title since Alan Gilbert’s inaugural season, following Magnus Lindberg, Mr. Rouse’s compositions and musical insights will be highlighted on subscription programs; in the Philharmonic’s appearance at the Spring For Music festival; in the NY PHIL BIENNIAL; on CONTACT! events; and in the ASIA / WINTER 2014 tour. Mr. Rouse said: “Part of the experience of music should be an exposure to the pulsation of life as we know it, rather than as people in the 18th or 19th century might have known it. It is wonderful that Alan is so supportive of contemporary music and so involved in performing and programming it.” 2 Alan Gilbert said: “I’ve always said and long felt that Chris Rouse is one of the really important composers working today. -

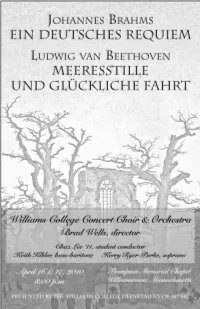

4-16-10 Concert Choir Prog

**Program** Ludwig van Beethoven Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt, opus 112 (1770-1827) (“Calm Seas and Prosperous Voyage”) Woo Chan “Chaz” Lee ’11, student conductor Johannes Brahms Ein deutsches Requiem, nach Worten (1833-1897) der heiligen Schrift, opus 45 (“A German Requiem, To Words of the Holy Scriptures”) I. Selig sind, die da Leid tragen II. Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras III. Herr, lehre doch mich IV. Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen V. Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit VI. Denn wir haben hie keine bleibende Statt VII. Selig sind die Toten Keith Kibler, bass baritone Kerry Ryer-Parke, soprano No photography or recording without permission Please turn off or mute cell phones, audible pagers, etc.. Biographies Woo Chan “Chaz” Lee, student conductor Woo Chan “Chaz” Lee is a junior Music and Comparative Literature major from Seoul, South Korea. He sings with the Williams Concert and Chamber choirs and is one of this year’s student conductors. He also sings with the Williams Jazz Ensemble and has performed with Symphonic Winds in multiple capacities. He has studied voice with Brad Wells and Erin Nafziger as well as piano and organ with Ed Lawrence. Keith Kibler, bass-baritone “The bright heft and fully-focused center of a Helden-baritone,” “His aria could not have been more intense or eloquent,” “A thrillingly centered voice with heroic ring,” “The model of what a bass-baritone should be.” These are just a few of the critical accolades bass-baritone Keith Kibler has received for recent appearances. He was cited as a promising singer while still an undergraduate by The New York Times and made his national debuts at the age of twenty-four with the Opera Theatre of St. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ralph Vaughan Williams – Symphony No. 5 in D Major Born October 12, 1872, Gloucestershire, England. Died August 26, 1958, London, England. Symphony No. 5 in D Major Vaughan Williams made his first sketches for this symphony in 1936, began composition in earnest in 1938, completed the work early in 1943, and made minor revisions in 1951. The first performance was given on June 24, 1943, at a Promenade Concert in Royal Albert Hall, with the composer conducting the London Philharmonic. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Vaughan Williams’s Fifth Symphony were given at Orchestra Hall on March 22 and 23, 1945, with Désiré Defauw conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on April 16, 17, and 18, 1987, with Leonard Slatkin conducting. Very early in the twentieth century, Ralph Vaughan Williams began to attract attention as a composer of tuneful songs. But, he eventually declared himself a symphonist, and over the next few years—the time of La mer, Pierrot lunaire, and The Rite of Spring—that tendency alone branded him as old-fashioned. His first significant large-scale work, the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis, composed in 1910, is indebted to the music of his sixteenth-century predecessor and to the great English tradition. His entire upbringing was steeped in tradition—he was related both to the pottery Wedgwoods and Charles Darwin.