ETD Template, and Matthew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of James Joyce on the Work of Juan Ramón Jiménez

Papers on Joyce 2 (1996): 47-64 The Impact of James Joyce on the Work of Juan Ramón Jiménez MARISOL MORALES LADRÓN Universidad de Alcalá de Henares The work of the Andalusian writer Juan Ramón Jiménez probably constitutes one of the earliest indications of James Joyce's impact on Spanish literature. Born in 1881, only a year before Joyce, Juan Ramón wrote between the years of 1941 and 1954 a series of critical essays in which we find one dedicated to Joyce, and two long poems in prose entitled Espacio (Space) and Tiempo (Time), the readings of which bear some markedly Joycean traits, notably in their use of the interior monologue and their overall consideration of time and space. A more detailed exploration of Juan Ramón's work demonstrates that his knowledge of Joyce, a factor underlined by the considerable number of occasions in which he is mentioned, is far greater than one might have hoped to expect from two such close contemporaries. In this discussion I should like to offer a brief consideration of Joyce's impact on Juan Ramón's literary career. My approach will be essentially twofold: to analyze the presence of Joycean traits in Juan Ramón's work, and to consider the surprising number of parallels in their personal lives and literary careers, parallels which exerted similar degrees of influence on their intellectual evolution. Although to some extent Juan Ramón is identified in the Spanish tradition as a poet more than a writer of prose, one of the most striking aspects of his work is the fact that even though the majority of his canon was originally written in verse, at the end of his life he decided to recast it in prose form, for he no longer saw such a clear distinction between the genres. -

1 Dictée Du 14 Janvier 2019 : Texte De Victor Hugo * Spectre

Dictée du 14 janvier 2019 : texte de Victor Hugo La monarchie de Juillet est le nom du régime politique de la France de juillet 1830 à février 1848. C'est une monarchie constitutionnelle avec pour roi Louis-Philippe Ier. Le régime politique repose sur le suffrage censitaire qui donne le pouvoir à la petite partie la plus riche de la bourgeoisie française. Hier, 22 février [1846], j'allais à la Chambre des pairs. Il faisait beau et très froid, malgré le soleil de midi. Je vis venir rue de Tournon un homme que deux soldats emmenaient. Cet homme était blond, pâle, maigre, hagard ; trente ans à peu près, un pantalon de grosse toile, les pieds nus et écorchés dans des sabots avec des linges sanglants roulés autour des chevilles pour tenir lieu de bas ; une blouse courte et souillée de boue derrière le dos, ce qui indiquait qu'il couchait habituellement sur le pavé, nu-tête et les cheveux hérissés. Il avait sous le bras un pain. Le peuple disait autour de lui qu'il avait volé ce pain et que c'était à cause de cela qu'on l'emmenait. En passant devant la caserne de gendarmerie, un des soldats y entra et l'homme resta à la porte, gardé par l'autre soldat. Une voiture était arrêtée devant la porte de la caserne. C'était une berline armoriée portant aux lanternes une couronne ducale, attelée de deux chevaux gris, deux laquais en guêtres derrière. Les glaces étaient levées mais on distinguait l'intérieur tapissé de damas bouton d'or. -

Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1

Teaching Classical Languages Volume 10, Issue 2 Kopestonsky 71 Never Out of Style: Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1 Theodora B. Kopestonsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT Students often struggle to interpret Latin poetry. To combat the confusion, teachers can turn to a modern parallel (pop music) to assist their students in understanding ancient verse. Pop music is very familiar to most students, and they already trans- late its meaning unconsciously. Building upon what students already know, teach- ers can reframe their approach to poetry in a way that is more effective. This essay shows how to present the concept of meter (dactylic hexameter and elegy) and scansion using contemporary pop music, considers the notion of the constructed persona utilizing a modern musician, Taylor Swift, and then addresses the pattern of the love affair in Latin poetry and Taylor Swift’s music. To illustrate this ap- proach to connecting ancient poetry with modern music, the lyrics and music video from one song, Taylor Swift’s Blank Space (2014), are analyzed and compared to poems by Catullus. Finally, this essay offers instructions on how to create an as- signment employing pop music as a tool to teach poetry — a comparative analysis between a modern song and Latin poetry in the original or in translation. KEY WORDS Latin poetry, pedagogy, popular music, music videos, song lyrics, Taylor Swift INTRODUCTION When I assign Roman poetry to my classes at a large research university, I re- ceive a decidedly unenthusiastic response. For many students, their experience with poetry of any sort, let alone ancient Latin verse, has been fraught with frustration, apprehension, and confusion. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Baudelaire and the Rival of Nature: the Conflict Between Art and Nature in French Landscape Painting

BAUDELAIRE AND THE RIVAL OF NATURE: THE CONFLICT BETWEEN ART AND NATURE IN FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING _______________________________________________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS _______________________________________________________________ By Juliette Pegram January 2012 _______________________ Dr. Therese Dolan, Thesis Advisor, Department of Art History Tyler School of Art, Temple University ABSTRACT The rise of landscape painting as a dominant genre in nineteenth century France was closely tied to the ongoing debate between Art and Nature. This conflict permeates the writings of poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. While Baudelaire scholarship has maintained the idea of the poet as a strict anti-naturalist and proponent of the artificial, this paper offers a revision of Baudelaire‟s relation to nature through a close reading across his critical and poetic texts. The Salon reviews of 1845, 1846 and 1859, as well as Baudelaire‟s Journaux Intimes, Les Paradis Artificiels and two poems that deal directly with the subject of landscape, are examined. The aim of this essay is to provoke new insights into the poet‟s complex attitudes toward nature and the art of landscape painting in France during the middle years of the nineteenth century. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to Dr. Therese Dolan for guiding me back to the subject and writings of Charles Baudelaire. Her patience and words of encouragement about the writing process were invaluable, and I am fortunate to have had the opportunity for such a wonderful writer to edit and review my work. I would like to thank Dr. -

Baroque Poetics and the Logic of Hispanic Exceptionalism by Allen E

Baroque Poetics and the Logic of Hispanic Exceptionalism by Allen E. Young A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Francine Masiello, Co-chair Professor Michael Iarocci, Co-chair Professor Robert Kaufman Fall 2012 Abstract Baroque Poetics and the Logic of Hispanic Exceptionalism by Allen Young Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professors Francine Masiello and Michael Iarocci, Chairs In this dissertation I study the how the baroque is used to understand aesthetic modernity in twentieth-century Spain and Latin America. My argument is that the baroque, in contemporary Hispanic and Latin American studies, functions as a myth of cultural exceptionalism, letting critics recast avant-garde and postmodern innovation as fidelity to a timeless essence or identity. By viewing much contemporary Spanish-language as a return to a baroque tradition—and not in light of international trends—critics in effect justify Spain and Latin America’s exclusion from broader discussions of modern literature. Against this widespread view, I propose an alternative vision drawn from the work of Gerardo Diego, José Lezama Lima and Severo Sarduy. These authors see the baroque not as an ahistorical, fundamentally Hispanic sensibility located outside the modern, but as an active dialogue with the wider world. In very different ways, they use the baroque to place the Hispanic world decidedly inside global aesthetic modernity. In contrast to most contemporary scholarship on the topic, I do not take the baroque to be a predefined aesthetic practice, readily identifiable in seventeenth- or twentieth- century authors. -

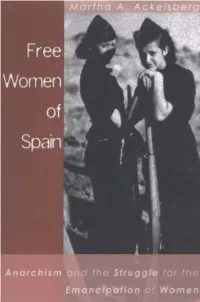

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Nicanor Parra and the Chaos of Postmodernity Miguel-Angel Zapata Associate Professor Department of Romance Languages and Literatures

Nicanor Parra and the Chaos of Postmodernity Miguel-Angel Zapata Associate Professor Department of Romance Languages and Literatures t would be risky to claim that the mode, with a tendency toward verse, work of a Latin American poet falls and in others we see the complete squarely within a given literary domination of the prose poem. But there movement. Contemporary Latin is also a luminosity that cannot be easily Nicanor Parra, 2005. Photo by Miguel-Angel Zapata. American poetry is split along identified, and the reason is that the various semantic lines, and tends poem’s interior light multiplies and pues, y que vengan las hembras de la I 1 toward a progressive deterritorialization. acquires different meanings on the page. pusta, las damas de Moravia, las egip- However, criticism of Latin American It cannot be said that the poetry of cias a sueldo de los condenados. poetry tends to fall into the dangerous Mutis is surrealistic or transparent or habit of gratuitous classifications, which that it tends only toward the practice Enough of the feverish and agitated vary according to the terminology of a of the prose poem; we can say, rather, men demanding in shrill voices what particular literary theory or according to that his poetry revitalizes language by is now owed to them! Enough of personal invention. Usually there are means of its sonorous multiplicity. fools! The hour of disputes between some anthologies that try to delimit the Mutis does not struggle to make his the quarrelsome, foreign to the order territory of poetry, categorizing it poems unintelligible (for that would of these places, is over. -

Bibliographie

BIBLIOGRAPHIE I. ŒUVRES DE VICTOR HUGO A. ŒUVRES COMPLETES 1. Éditions publiées du vivant de Victor Hugo 2. Les grandes éditions de référence. B. ŒUVRES PAR GENRES 1. Poésie Anthologies Recueils collectifs Œuvres particulières 2. Théâtre Recueils collectifs Divers Œuvres particulières 3. Romans Recueils collectifs L’Intégrale Œuvres particulières 4. Œuvres « intimes » Correspondance Journaux et carnets intimes 5. Littérature et politique Littérature Politique Divers 6. Voyages 7. Fragments et textes divers 8. Œuvre graphique II. L’HOMME ET SON ŒUVRE Études d’ensemble A. L’HOMME 1. Biographies 2. Victor Hugo et ses contemporains Ses proches Le monde artistique et littéraire 3. Aspects, événements ou épisodes de sa vie Exil Lieux familiers Politique Voyages B. L’ŒUVRE 1. Œuvre littéraire Critique et interprétation Hugo vu par des écrivains du XXe siècle Esthétique Thématique Influence, appréciation 2. Genres littéraires Poésie Récits de voyage Romans Théâtre 3. Œuvres particulières 4. Œuvre graphique, illustration I. ŒUVRES DE VICTOR HUGO A. ŒUVRES COMPLÈTES Cette rubrique présente une sélection d’éditions des œuvres complètes de Victor Hugo : d’abord celles parues du vivant de l’auteur, puis quatre éditions qui font autorité. On trouve plus loin, classées aux différents genres abordés par l’écrivain : la collection « L’Intégrale », publiée par les Éditions du Seuil (Théâtre, Romans, Poésie) et divers recueils collectifs, en particulier les « Œuvres poétiques », publiées par Gallimard dans la « Bibliothèque de la Pléiade ». 1. Éditions publiées du vivant de Victor Hugo Il ne s’agit pas d’œuvres complètes au vrai sens du terme, puisque Victor Hugo continuait à écrire au moment même de leur publication. -

Horace - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace(8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words." Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings". Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive to modern audiences. His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep") but for others he was, in < a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/john-henry-dryden/">John Dryden's</a> phrase, "a well-mannered court slave". -

The Concrete Poetry of Mathias Goeritz: a Graphic and Aural Analysis

Natalia Torija-Nieto HA-551-05/06: History of Sound Art December 19, 2014 FA14 | Pratt Institute | Instructor: Charles Eppley The Concrete Poetry of Mathias Goeritz: a Graphic and Aural Analysis This essay focuses on the work of German-Mexican artist Mathias Goeritz as influenced by the performances and writings of Hugo Ball and Dada sound art and poetry. Goeritz’s rather spiritual approach towards the pursuit of the Gesamtkunstwerk, are key to understand the roots of his work and his short but noteworthy venture into concrete poetry. The aural component in the realization of his work is associated with the adapted readings and performances of this kind of poetry worldwide during the 1950s and 60s with artists such as Eugen Gomringer, Augusto and Haroldo de Campos, Décio Pignatari, and Mary Ellen Solt, among others. By historicizing the main influences and artists that inspired these poets, I will explore the consequent concrete poetry movement of the post-war era that is visible through their works, particularly on Mathias Goeritz. !1 In his essay on concrete poetry, R.P. Draper defines the term as “the creation of verbal artifacts which exploit the possibilities, not only of sound, sense and rhythm—the traditional fields of poetry—but also of space, whether it be the flat, two-dimensional space of letters on the printed page, or the three-dimensional space of words in relief and sculptured ideograms.”1 Concrete poetry challenges the conventional expressiveness of traditional poetry by considering its play of visual, graphic, and aural qualities. This essay presents examples of the work of Mathias Goeritz and his Latin American contemporaries, particularly the Brazilian group Noigandres formed by Haroldo and Augusto de Campos and Décio Pignatari, who first introduced the term “concrete poetry” in 1953. -

La Traducción Como Interpretación

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert “Transfer” IV: 2 (noviembre 2009), pp. 40-52. ISSN: 1886-5542 TRANSFERRING U.S. LATINO POETS INTO THE SPANISH- SPEAKING WORLD1 Lisa Rose Bradford, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Translation is slippery art that compounds the problems of the inherent instability of language with the unruly process of duplicating it in another system. The sliding that occurs in the translation of multicultural poetry is even more pronounced since the distance from “the norm” becomes greater and greater. This is true firstly because poetry is a genre that strives for verbal concision and innovation in a playful defiance of norms that pique the reader’s imagination; and secondly because the multilingual poet often involves a second language —either in its original form or as a translation into the language of composition—to enhance sound and cultural imagery. Latino poetry generally glides along on the linguistic and cultural tension inherent in both its poeticity and its English/Spanish and Latino/Anglo dualities that challenge normative discourse. Therefore, the translation of this verse must also produce for the reader a similarly slippery tension, a task that Fabián Iriarte and I constantly grappled with in the editing of a recent bilingual anthology, Usos de la imaginación: poesía de l@s latin@s en EE.UU. This book began as an experiment in heterolingual translation in general, and after selecting eleven Latino poets for an anthology —Rafael Campo, Judith Ortiz Cofer, Silvia Curbelo, Martín Espada, Diana García, Richard García, Maurice Kilwein Guevara, Juan Felipe Herrera, Pat Mora, Gary Soto and Gloria Vando—we spent two years researching and rehearsing versions in readings and seminars offered in the universities of Mar del Plata and Córdoba in order to test the success of our translation strategies.2 There were many aspects to be considered before deciding on the best approach to translating this verse.