The Impact of James Joyce on the Work of Juan Ramón Jiménez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ackelsberg L

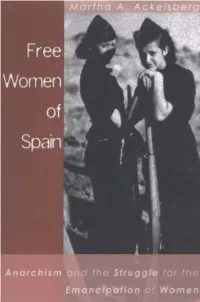

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

El Centro De Estudios Históricos Durante La Guerra Civil Española 1073

Hispania Vol 56, Núm. 194 (1996) Híspanla, LVI/3, num. 194 (1996) EL CEMTRO DE ESTUDIOS HISTÓRICOS DURANTE LA GUERRA CIVIL ESPAÑOLA (1936«1939) por PRUDENCIO GARCÍA ISASTI Universidad Autónoma de Madrid RESUMEN: El artículo parte de la hipótesis de que un cierto número de intelectuales republicanos de prestigio decidieron quedarse en España durante la Gue- rra Civil, y continuar sus actividades habituales, considerando que con ello contribuían a combatir lo que denominaban «barbarie fascista». El objetivo principal es realizar una investigación sectorial acerca de la importancia que éstas pudieron revestir, más allá su utilización propagan- dística durante la guerra, o de su mitificación, subestimación o demoni- zación durante el franquismo. Para ello se escoge un organismo concreto, el Centro de Estudios Históricos, y se describen detalladamente todas sus actividades durante la guerra: su cierre en noviembre de 1936, su reaper- tura y breve florecimiento al calor del movimiento antifascista, y su lento declinar hasta el fin de la guerra. PALABRAS CLAVE. Historia Intelectual Española, Guerra Civil Española, Cen- tro de Estudios Históricos, Antifascismo ABSTRACT: The article starts from the hypothesis that some famous republican intellec- tuals decided to stay in Spain during the Civil War, going on their usual acti- vities, thinking in this way, they helped to fight what they called «fascist barbarity». The main purpose is to put into effect a sectorial research work on the bases of the importance of this kind of activities, trying to avoid the use of propaganda made during the war, myths or understimations made during the period of Franco's dictatorship. -

Download (8Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/106530 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY DOCUMENT SUPPLY CENTRE TITLE POC IRV «NO IDCOLOGYi THE ErrECT Or THE POLITICS Or THE INTERWAR YEARS AMO THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR ON THE POETRY Or CESAR VALLEJO AUTHOR George Robert Lamble INSTITUTION and DATE THE UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK, / Attention is drawn to the fact that the copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. THE BRITISH LIBRARY DOCUMENT SUPPLY CENTRE 20 C A m ETNA é POE FRY AND IDCOLOCYi THE EFFECT OF THE POLITICS OF THE INTERWAR YEARS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR ON THE POETRY OF CESAR VALLEJO George Robert Lambie Submitted in fulfilment of the Regulations for the Degree of Ph.D in History, University of Warwick. July 1987 'During the lifetime of great revolutionaries the oppressing classes constantly hounded them, received their theoriea with savage malice, the most furious hatred and the most unscrupulous csmpsigns of lies and slander. -

1 Juan Ramón Jiménez En Las Américas: Entre La Ética Y La Estética

Juan Ramón Jiménez en las Américas: Entre la ética y la estética, EE. UU. y el cono sur: 1936, 1939-1951 Quedar aislado culturalmente en el territorio de acogida es uno de los obstáculos más nocivos que afectan a los creadores en el destierro En el extenso espacio del exilio de las Españas de 1939, se forjó una nomenclatura benigna para designar como “transtierro”, según lo llamó José Gaos, el caso de la recepción positiva en un entorno afín: caso de los intelectuales españoles que se acogieron al asilo de países como Cuba o México.1 En esa línea de pensamiento, Juan Ramón se sintió “coterrado” en sus diferentes residencies caribeñas (Puerto Rico 1936 y 1951-1958, Cuba 1937-1939). Pero durante más de la mitad de su exilio, en la época de EE. UU., entre 1939 y 1951, el escritor permaneció segregado tras el muro lingüístico de la lengua inglesa que conocía pero que no le agradaba utilizar.2 Aprovechando la capacidad nativa de su fiel compañera, Zenobia Camprubí, que se ocupaba de los detalles de la vida práctica, logró sobrevivir durante aquellos años aunque la imposibilidad de hablar español de forma cotidiana o la asociación de paisajes locales con el recuerdo de espacios españoles le sumió repetidas veces en varias depresiones tanto en Coral Gables como en Washington, por lo que Zenobia decidió trasladarlo a Puerto Rico en 1951 para que recuperase su tono vital, lo cual logró hasta el fallecimiento de su mujer en 1956. “El destierro de mi lengua diferente, superior a toda alegría, a toda indiferencia, a toda libertad, a toda pena. -

Divine Madness

CHAPTER VI: Divine Madness Very little has been written about the theme of madness in the work of Antonio Machado although it appears in some of his poems and is an important aspect of his metaphysical thought. In spite of its importance for Cervantes and those writers who have been inspired by Don Quijote, madness is not a frequent topic in Spanish poetry, and looking at Machado's work from the point of view of this unusual perspective will permit us to clarify some important aspects of his religious and philosophical thought. Most people would regard a "madman" as a lunatic who has lost his mind and they would say that "madness" is state of insanity resulting from the loss of reason. Normally, the loss of reason or irrational conduct is a mental state that should be avoided. But that is not the case in Machado's work as we see in these words of his apocryphal philosopher, Juan de Mairena: "Among us the weakness is our reason, perhaps because the most robust and virile condition is, as Cervantes recognized, a state of madness."1 This may be the reason why Mairena himself had "the reputation for being a madman" (OPP, p. 499), and it has also been said of Machado's other apocryphal philosopher, Abel Martín, that "he must be crazier than a loon" (OPP, p. 503). In Machado's poetry and in the Apocryphal Songbook madness symbolizes the attitude of the person who rebels against the limits of reason and allows himself to be governed by his non-rational consciousness: intuition, idealism, poetic thought, etc. -

De Aurora De Albornoz, En El Contexto Del Memorialismo Femenino Del Exilio

CRONILÍRICAS , DE AURORA DE ALBORNOZ, EN EL CONTEXTO DEL MEMORIALISMO FEMENINO DEL EXILIO Begoña CAMBLOR PANDIELLA Universidad de Oviedo [email protected] Resumen: Cronilíricas La obra , de Aurora de Albornoz, publicada póstu - mamente en 1991, es analizada en este estudio tomando como base contextual y como modelo de comparación la producción de las memorialistas del exilio, especialmente María Teresa León, Concha Méndez o María Campo Alange. Abstract: Cronilíricas Aurora de Albornoz’s , published posthumously in 1991, is analized in this paper taking as contextual base and model of com - parison, the literary production of the memorialist women writers of the exile, such as María Teresa León, Concha Méndez or María Campo Alange. Palabras clave: Cronilíricas Aurora de Albornoz. Memorialismo. Exilio es - pañol. Key Words: Cronilíricas Aurora de Albornoz. Literary Memorialist. Spa - nish exile. UNED. Revista 19 (2010), págs. 235-253 © Signa 235 BEGOÑA CAMBLOR PANDIELLA En 1991, un año después del falleCcrimonieilnírtoicdaes.ACuorlolraagde e Albornoz, la edi - torial madrileña Devenir publicaba , uno de los textos más personales de la escritora; supone esta obra una incursión decidida en el terreno del memorialismo, aunque la exploración se hace desde una posición de frontera en la que llegamos a confundir motivaciones, discursos e incluso protagonistas diversos. Definir esa diversidad es, precisamente, el objetivo de este estudio, en el que se toma como pauta y marco de reflexión la frecuen - te presencia del género memorialístico en la producción literaria de las es - critoras exiliadas, quienes acompañan a Aurora de Albornoz como raíces ins - piradoras y motivadoras tanto en el aspecto creativo como en el vital. -

Resumen Palabras Clave Mauricio Escobar Deras A

MAURICIO ESCOBAR DERAS S A METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH ÑOLE A TO THE SPANISH REPUBLICAN EXILE RETURN P ES S UNA APROXIMACIÓN METODOLÓGICA NO A AL RETORNO DE EXILIADOS REPUBLICANOS ESPAÑOLES EPUBLIC R S Resumen Abstract DO A Este artículo examina las estrategias que los This paper examines the strategies that first- XILI E E republicanos exiliados de la primera generación generation exiled republicans selected to D seleccionaron para repatriarse a España. repatriate to Spain after the end of the Spanish Reúne los tipos de retornos que tuvieron lugar Civil War. It assorts the types of returns that entre 1939 y 2010, analizando las estrategias took place between 1939 to 2010, analyzing ETORNO de repatriación. Los datos provienen de the repatriation strategies and noting the R dos base de datos compiladas a través de challenges they navigated. The data is from AL A trabajos académicos y una encuesta de redes two sets of databases compiled via scholarly sociales completada por los descendientes. work and a social media survey filled out by the Concluye con nueve tipos de retornos y sus descendants. It concludes with nine types of correspondientes estrategias. returns and their corresponding strategies. Palabras clave Key words 20 CIÓN METODOLÓGIC Exilio, Franquismo, Guerra Civil Española, Exile, Francoism, Repatriation, Spanish Civil MA Tipos de retorno. War, Types of return. APROXI A Mauricio Escobar Deras N U Universidad de Granada. Instituto de Migraciones. ETURN R Currently working on a Ph.D University of Gra- XILE nada, focusing on combining immigration stu- E N dies with history. Previously, MA Université de A Savoi in communications; MA California State Univerity in History, Northridge; BA University of California, Santa Cruz in History. -

Spring 2017 CLLAS Notes

Cllas Notes Vol. 8 Issue 2 Spring 2017 DIRECTOR’S LETTER he winter term featured a Dreamers, TDucks & DACA Info-Session held Feb. 28 in the EMU. Led by Ellen McWhirter, Ann Swindells Professor in Counseling Psychology, and the UO Dreamers Working Group, the session presented strategies for supporting UO undocumented, DACAmented, and students from mixed status families. Documents drawn from this presentation are housed on our CLLAS website at: http://cllas.uoregon.edu/resources/ know-your-rights/basic-info-to-know/ CLLAS kicked off spring with a Documenting Latino Roots: 2017 cohort marks the 4th significant panel discussion in response to the new political environment. “Immigration iteration of this popular hands-on class Policy and Coalition-Building in the Age of very two years, UO offers a two-term series that teaches students about Latino history in Oregon. Trump” was moderated by Dan Tichenor, EThe second term class culminates in a documentary film project carried out by each student. Three professor in the Department of Political students from the 2017 class—taught by Science and senior faculty fellow with the Lynn Stephen and Gabriela Martínez— Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. It share synopses of their projects. featured Larry Kleinman, director of National Initiatives for CAPACES Leadership Institute; Heidi Rangel: Documentary Roberta Phillip-Robbins, J.D., executive Synopsis of NORMA director of MRG Foundation; and Guadalupe The documentary I am producing, titled Quinn, Group Latino de Accion Directa de “NORMA,” captures the journey of Norma Lane County. They provided updates on Scovell from her upbringing in Del Rio to immigration policy from their perspective, her current residence in Oregon. -

Boletín N° 49 Mayo De 1976

49 Mayo 1976 Sumario ENSAYO 3 El secreta projesional de los periodistas, por Angel Benito. 3 NOTICIAS DE LA FUNDACION 23 Publicaciones 23 Estudio hispanico-britanico sobre Gibraltar 23 Rosa Chacel y su «Barrio de Maravillas». 25 Biblioteca de la Fundaci6n 26 Entrega de la medalla Ibarra, por «Baleares». 27 Literatura 28 Jose Hierro y Aurora de Albornoz. 28 Cursos Universitarios 31 Alfonso Perez Sanchez: dos ultimas lecciones sobre el Museo del Prado. 31 Luis Sanchez Agesta: «Las antitesis del desarrollo». 33 Juan Cano Ballesta: «Tradici6n y renovaci6n en Miguel Hernandez». 36 Encuentros Cientificos 38 Homenaje al profesor Sraffa. 38 Cursillo de educaci6n medica. 40 Arte 43 Concluye la Exposici6n Dubuffet. 43 Aplazada la exposici6n de Bacon. 43 Exposici6n permanente. 45 Musica 46 Actuacion del «Renaissance Group» de Escocia. 46 Estudios e investigaciones 47 Memoria del Instituto de Bioquimica Clinica-Fundacion Juan March. 47 Trabajos finales aprobados. 48 OTRAS FUNDACIONES 49 Calendario de actividades para mayo 51 ..... ) l ENSAYO* EL SECRETO PROFESIONAL DE LOS PERIODISTAS Par Angel Benito Catedratico de la Teoria General de la Informacion en la Universidad Complutense. «Un silencio nuestro por el derecho al silencio» (Geno ves, 14 de t febrero de 1976). NADIE, puede negar, a la vista de los acontecimientos vividos por nuestro pais durante los primeros meses de reinado de don Juan Car los I que, la informacion en gene as ral y la prensa de modo muy es :in ite pecifico, han protagonizado buena ia. parte de las noticias relativas al iniciado proceso de liberalizacion ANGEL BENITO, Periodis politica emprendido por e1 primer ta, Primer Presidente de la Gobierno de la Monarquia, Los Asociacion Internacional de Profesores e Investigadores periodistas y su trabajo diario, sin de Ciencias de Ia Informa pretenderlo los propios profesio cion, Primer Miembro espa nales, han tenido que dar noticia fiol del Instituto Internacio nal de Prensa de Zurich. -

La Escritura Creativa E Intelectual De La Poeta Aurora De Albornoz

Revista de Estudios Hispánicos, VI. 1, 2019 pp. 41-61, ISSN 0378.7974 HACIA UNA VISIÓN TRANSATLÁNTICA: LA ESCRITURA CREATIVA E INTELECTUAL DE LA POETA AURORA DE ALBORNOZ TOWARD A TRANSATLANTIC VISION: THE CREATIVE AND INTELLECTUAL WRITING BY THE POET, AURORA DE ALBORNOZ Carlos Manuel Rivera Bronx Community College City University of New York Correo electrónico:[email protected] « . « quietud vacía, Auras que siembran mármoles dormidos, Carboinael Rixema Resumen La poeta española, Aurora de Albornoz aporta con su escritura desde sesenta a los actuales estudios transatlánticos que nos revelan las conexio- nes y desconexiones culturales, políticas y económicas entre España, La- tinoamérica, el Caribe y los Estados Unidos. Su trabajo genera un debate académico que desmantela el límite espacial y nacional que proponen los discursos hegemónicos a la escritura del exilio. Su póstumo libro Croni- líricas. Collage (1991) nos muestra en una manera más explícita a una España desde el exilio en Puerto Rico y una creación poética e intelectual de un Caribe hispano y una Latinoamérica desde la península, proyectán- dose con esto la iniciación de unos estudios hispánicos transatlánticos e interdisciplinarios, o quizás transdisciplinarios. 41 Revista de Estudios Hispánicos, U.P.R. Vol. 6 Núm. 1, 2019 Palabras claves: estudios transatlánticos, poesía española, exilio, literatu- ra latinoamericana Abstrac The Spanish poet Aurora de Albornoz contributes with her writing from the exile in Puerto Rico and from the returning to Spain in the sixties to the recent Transatlantic Studies. Her writing reveals cultural, political, and economic connections and disconnections between Spain, Latin Ame- rica, the Caribbean, and United States. -

A Poetic Complement to Reason: Heterogeneity and the Other in the Work of Antonio Machado

A POETIC COMPLEMENT TO REASON: HETEROGENEITY AND THE OTHER IN THE WORK OF ANTONIO MACHADO A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Anastasiya Stoyneva August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Christopher Soufas, Dissertation Advisor Dr. Víctor Pueyo Zoco, Internal Reader Dr. Salvatore Poeta, Villanova University, External Reader ABSTRACT A Poetic Complement to Reason: Heterogeneity and the Other in the work of Antonio Machado examines some of the late work of the Spanish writer. By focusing on his apocryphal project and especially on its two major texts, De un cancionero apócrifo and Juan de Mairena, I seek to show that the author’s philosophical endeavors are intrinsically related to the major trends within European thought during the tumultuous first decades of the new century. Turning to the problem of reason and the rift that separates its conceptual and non-conceptual sides, Machado advances important understandings of ontological and epistemological nature that remain understudied. The conceptions of human knowledge, life, and freedom that the author elaborates evince his desire to reevaluate the dominant idealist ones and even to part ways with this tradition. From today’s viewpoint, these notions are interesting because they continue to resonate with the ones we hold today. This project, therefore, intervenes in Machado’s scholarship by addressing the theoretical stance of the author and its relationship to issues like emancipation, equality, and communal life that remain pressing. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ..............................................................................................v PREFACE .......................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

La Mirada Panhispánica De Aurora De Albornoz: Poesía, Memoria Y Revolución

Número 17, Año 2016 La mirada panhispánica de Aurora de Albornoz: poesía, memoria y revolución The Pan-Hispanic View of Aurora de Albornoz: Poetry, Memory And Revolution Alba González Sanz (Universidad de Oviedo) [email protected] RESUMEN La obra de Aurora de Albornoz (Luarca 1926—Madrid 1990), tanto en su faceta creativa como en su amplísima producción académica, maneja coordenadas que ponen en diálogo las tradiciones culturales y políticas de España y de América Latina. En su libro Cronilíricas, la autora rememora la universidad en el exilio puertorriqueño, la influencia de Juan Ramón Jiménez en su poesía, la conciencia política que impele al regreso a Es- paña a finales de la década de 1960 y todo el esfuerzo de cambio polí- tico y reivindicación cultural que realizó durante la Transición. En esas memorias publicadas póstumamente, Albornoz aúna una visión ética y estética del mundo que relaciona el Modernismo hispanoamericano con los procesos revolucionarios y democráticos del último cuarto del siglo XX en ambos lados del Atlántico. Construye así una mirada sobre la historia española de la pasada centuria en la que la poesía, el cambio democrático y las relaciones fraternales con las repúblicas americanas delinean su pro- pia identidad como escritora e intelectual comprometida. Palabras clave: Exilio; Autobiografías; Modernismo; Transición; Auro- ra de Albornoz. ABSTRACT The work of Aurora de Albornoz (Luarca 1926—Madrid 1990), both in its creative side and in its vast academic production, manages to put in dialogue the cultural and political traditions of Spain and Latin America. In her book Cronilíricas the author recalls her stay at the Puerto Rico University during her exile, the influence of Juan Ramón Jiménez in her poetry, the political awareness that impels her to return to Spain in the late 1960s and all the efforts of political change and cultural claim made during the Transición.