Mauritian Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life on Sugar Estates in Colonial Mauritius

Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 1-10 ISSN 2334-2420 (Print) 2334-2439 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jaa.v6n2a1 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jaa.v6n2a1 Life on Sugar Estates in Colonial Mauritius Mrs Rashila Vigneshwari Ramchurn1 Abstract This research paper seeks to examine life of descendants of indentured labourers on sugar estates in Mauritius. Attempt will be made to unravel gender disparity in all its forms. This study demonstrates how the bourgeoisie exploited and dominated the proletariat and preserved the status quo from the Marxist perspective as well as other theoretical approaches. Empirical data has been collected by conducting qualitative research using the face to face unstructured interview with elders aged 70 years to 108 years in the Republic of Mauritius and critical analysis of speeches of the leader of the Mauritius Labour Party. Secondary data has also been employed through qualitative research. The interviews were recorded in the year 2016,2018 and 2018 on digital recorder, transcribed and translated in English. All of the researches have been carried out objectively in a systematic manner so as to erase any bias in the study conducted. 70% of modern Mauritians are descendants of the indentured labourers. 1.1. Introduction Mauritius is an island in the South West Indian Ocean. Four hundred years ago there was no indigenous population on the island. All the people in Mauritius are immigrants. Mauritius has known three waves of immigrants namely the Dutch, the French and the British. -

Unwind Mauritius Times Tuesday, July 13, 2021 13

66th Year -- No. 3694 Tuesday, July 13, 2021 www.mauritiustimes.com facebook.com/mauritius.times 18 Pages - ePaper MAURITIUS TIMES l “The talent of success is nothing more than doing what you can do, well”. -- Henry W. Longfellow ‘POCA states clearly that the Director of ICAC should not be under the direction or control of any other person... If he chooses to be subservient, it is not only his personal problem...’ By LEX + See Page 4-5 Accountability Global Minimum or Impunity? Corporate Tax Rate By Jan Arden + See Page 3 Five lessons on bringing truth back to politics from Britain's first female philosophy professor By Peter West, Durham University + See Page 2 By Anil Madan + See Page 5 Mauritius Times Tuesday, July 13, 2021 www.mauritiustimes.com Edit Page facebook.com/mauritius.times 2 The Conversation Economic Security, Five lessons on bringing truth back to politics Society’s Security from Britain’s first female n last Friday’s issue of this paper we published MT, in an article in l’express takes a position which an interview of Lord Meghnad Desai who counters the rosy picture that Lord Desai depicted philosophy professor requires no formal introduction to the Mauritian of the MIC. The article puts forth several arguments Ipublic, and who was Chairman of the Mauritius of a very technical nature, but the sum total is that Investment Corporation Ltd (MIC) - a creation of the things could have been done differently, so as to Bank of Mauritius set up in the context of the Covid- preserve financial soundness at the same time as 19 pandemic as its economic and social impacts meeting the objectives of supporting companies began to be felt. -

National Bibliography of Mauritius 2016 004.076

NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF MAURITIUS 2016 004.076 Mauritius Institute of Education. Information and Communication Technology : prevocational programme year 2 part 1 / Mauritius Institute of Education. - Réduit : Mauritius Institute of Education, 2016. - vii, 130 p. : col. ill. ; 30 cm. ISSN 9789990340754 1. Computer science – Study and teaching (Secondary) – Mauritius 2. Information technology – Study and teaching (Secondary) – Mauritius 070.5096982 Government Printing Department. Customer charter / Government Printing Department.- Pointe aux Sables : Government Printing Department, 2016. - [p.] : col. ill. ; 14 cm. 1. Mauritius – Government Printing Department 2. Printing, Public – Mauritius 144 Panday, Dattatreya. Existential questions / Dattatreya Panday. - Quatre-Bornes : Dattatrya Panday, 2016. - 160p. ; 21 cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 9789994911776 1. Humanism 2. Secular humanism 155.9042 Ministry of Labour, Industrial Relations, Employment and Training, Occupational Safety and Health Division. Work – related stress guidelines / Ministry of Labour, Industrial Relations, Employment and Training, Occupational Safety and Health Division. - Port-Louis : Ministry of Labour, Industrial Relations, Employment and Training, Occupational Safety and Health Division, 2016. - 18 p. ; 21 cm. Includes bibliographical references 1. Stress management 2. Stress (Psychology) – Prevention 172.2096982 Ministry of Civil Service & Administrative Reforms. Code of ethics for public officers / Ministry of Civil Service & Administrative Reforms. - Port-Louis : Ministry of Civil Service & Administrative Reforms. - 16 p. : col. ill. ; 21 cm. 1. Civil Service Ethics – Mauritius 2. Mauritius – Officials and employees – Ethics 173 Ministry of Gender Equality, Child Development and Family Welfare. Charter on family values / Ministry of Gender Equality, Child Development and Family Welfare. - Port-Louis : Ministry of Gender Equality, Child Development and Family Welfare, 2016.- unpaged. : ill. ; 15 cm. 1. Family 2. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright

Rohatgi, Rashi (2012) Fighting cane and canon: reading Abhimanyu Unnuth's Hindi poetry in and outside of literary Mauritius. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/16627 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Fighting Cane and Canon: Reading Abhimanyu Unnuth’s Hindi Poetry In and Outside of Literary Mauritius Rashi Rohatgi Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Languages and Cultures of South Asia 2012 Supervised by: Dr. Francesca Orsini and Dr. Kai Easton Departments of Languages and Cultures of South Asia School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 Declaration for PhD Thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all of the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Women and Politics in a Plural Society: the Case of Mauritius

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University WOMEN AND POLITICS IN A PLURAL SOCIETY: THE CASE OF MAURITIUS Town Ramola RAMTOHULCape of Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the UniversityAfrican Gender Institute University of Cape Town February 2009 Women and Politics in a Plural Society: The Case of Mauritius ABSTRACT This research is a socio-historical study of women and politics in the Indian Ocean Island of Mauritius. It traces the historical evolution of women‟s political engagement in social and women‟s movements as well as in the formal political institutions. The backdrop to this study was my interest in the field of women and politics and concern on women‟s marginal presence in the Mauritian parliament since women obtained the right to vote and stand for election in 1947, and until recently, the stark silences on this issue in the country. Mauritius experienced sustained democracy following independence and gained a solid reputation in terms of its stable democratic regime and economic success. Despite these achievements, the Mauritian democracy is deficient with regard to women‟s representation at the highest level of decision-making, in parliament. Moreover, the absence of documentation on this topic has rendered the scope of thisTown study broad. In this thesis I primarily draw on the postcolonial feminist writings to study women‟s political activism in social and women‟s movements. -

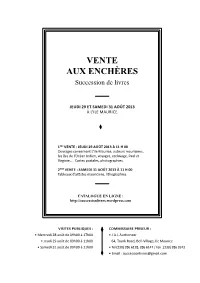

Vente Aux Enchères Succession De Livres

VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES Succession de livres JEUDI 29 ET SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À L’ILE MAURICE. 1ÈRE VENTE : JEUDI 29 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice, auteurs mauriciens, les îles de l’Océan Indien, voyages, esclavage, Paul et Virginie,…. Cartes postales, photographies. 2EME VENTE : SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Tableaux d’artistes mauriciens, lithographies. CATALOGUE EN LIGNE : http://successionlivres.wordpress.com VISITES PUBLIQUES : COMMISSAIRE PRISEUR : • Mercredi 28 août de 09h00 à 17h00 • J.A.L Auctioneer • Jeudi 29 août de 09h00 à 11h00 64, Trunk Road, Bell-Village, Ile Maurice • Samedi 31 août de 09h00 à 11h00 • Tel (230) 286 6128, 286 6147 / Fax : (230) 286 2673 • Email : [email protected] Information Une vente aux enchères concernant la succession de livres de M. …, bibliophile d’ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice ou publiés à L’Ile Maurice, se tiendra à L’Ile Maurice : • 1ÈRE VENTE : JEUDI 29 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice, auteurs mauriciens, les îles de l’Océan Indien, voyages, esclavage, Paul et Virginie,…. Cartes postales, photographies. •2EME VENTE : SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Tableaux d’artistes ayant vécu à Maurice, lithographies. - Le lieu de vente vous sera communiqué dans les meilleurs délais. Les ouvrages seront vendus par lots, organisés par thématiques (ex : histoire, esclavage, auteur, Madagascar, agriculture, religion,…). Un catalogue des lots est disponible en ligne à l’adresse suivante : http://successionlivres.wordpress.com où vous pouvez avoir accès à un moteur de recherche. Il est également téléchargeable en format pdf ici. -

Read L'express Weekly 25 February,2011

INTERVIEW] Ahmar Mahboob: “The prestige of Creole has to be raised.” > pp. 38-39 Insert N° 3 • Friday 25 February 2011 Editorial ] by Touria PRAYAG From ideology to personality ny entity which lasts for 75 years deserves our full res- pect. When a political party lasts that long and is in STRAIGHT TALK ] power, there is a lot to celebrate. Congratulations then Ato the Labour Party on an anniversary celebrated in a grand style but without too much wallowing in nostalgia or per- The Labour Party’s Diamond Jubilee sonality cult. The tribute paid to the founding fathers of the party > pp. 44 - 45 was justifi ed and, on the whole, measured. It is undeniable that the party has left an indelible footprint in every aspect of the history of this country and it still is a major force to be reckoned with in today’s Mauritius. But a celebration is not ISKON vs McDonald’s restricted to reminiscing about the past. It is also about refl ecting on the present and looking into the future. To claim that the present La- bour Party has not deviated from its original ideology is not entirely supported by facts. The ideology on which the party was founded has defi nitely moved towards more economic pragmatism, involving The burger of discord a range of measures verging, some might say, on neo-liberalism. Free market policies such as the removal of trade barriers, barriers to the infl ow and outfl ow of capital, the Stimulus Package and the Economic Restructuring and Competitiveness Programme, the fl at corporate tax rate to mention only a few cannot, by any yard stick, be qualifi ed as socialist in nature. -

THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE of MAURITIUS Published by Authority

THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF MAURITIUS Published by Authority No. 140 - Port Louis : Friday 13 November 2020 - Rs. 25.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL NOTICES 1742 — Legal Supplement 1743 1 to / Notice under the Land Acquisition Act 1782 ) 1783 — Medical Council of Mauritius - Amendments in the Annual List 2020 1784 — Medical Council of Mauritius - Notice 1785 — Notice of Change of Address 1786 — Notice under the Statutory Bodies Family Protection Fund Act 1966 - Statutory Bodies Family Protection Fund Board 2020 1787 j to 7 Clinical Research Regulatory Council - Clinical Trial Licences 1789 ‘ 1790 — Notice for Public Inspection of EIA Report - True Tesla Technologies (Mauritius) Ltd 1791 — Notice for Public Inspection of Decision on EIA Application 1792 — Notice under the Prevention of Corruption Act 2002 (PoCA 2002) 1793 to Notice under the Insolvency Act 2009 1795 . 1796 1 to . / Notice under the Companies Act 1869 J 1870 1 to ? Change of Name 1874 ) 1875 — Notice under the National Land Transport Authority 1876 1 to 7 Notice under the Patents, Industrial Designs & Trademarks Act 1878 ) LEGAL SUPPLEMENT See General Notice No. 1742 5054 The Mauritius Government Gazette General Notice No. 1742 of2020 Towards the East by State Land [TV201501/001118] on five metres and four LEGAL SUPPLEMENT centimetres (5.04m). The undermentioned Government Notice is Towards the. South by land occupied by Heirs published in the Legal Supplement to this number Matabadul JUGGURNATH on sixty four metres of the Government Gazette : and fifty six centimetres (64.56m). The Road Traffic (Extension of Time for Towards the West by land belonging to Bhai the Validity and Renewal of Licence for a Saoud JUGGROO on five metres (5.00m). -

AGTF Souvenir Magazine 2014

Table of Contents Editorial and Messages Editorial 4 Message from the President of the Republic of Mauritius ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Message from the Prime Minister ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Message from the Minister of Arts and Culture ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Message from the Lord Mayor of Port Louis ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 Article by the Director of the Aapravasi Ghat Trust Fund �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 11 Message from Professor Armoogum Parsuramen ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 14 1 AAPRAVASI GHAT WORLD HERITAGE SITE 15 The World Heritage Status �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 The -

Pdf, Consulté Le 10 Mars 2009

EchoGéo 10 | 2009 septembre 2009 / novembre 2009 La diaspora, instrument de la politique de puissance et de rayonnement de l’Inde à l’île Maurice et dans le monde Anouck Carsignol-Singh Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/echogeo/11329 DOI : 10.4000/echogeo.11329 ISSN : 1963-1197 Éditeur Pôle de recherche pour l'organisation et la diffusion de l'information géographique (CNRS UMR 8586) Référence électronique Anouck Carsignol-Singh, « La diaspora, instrument de la politique de puissance et de rayonnement de l’Inde à l’île Maurice et dans le monde », EchoGéo [En ligne], 10 | 2009, mis en ligne le 26 novembre 2009, consulté le 01 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/echogeo/11329 ; DOI : 10.4000/ echogeo.11329 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 mai 2019. EchoGéo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International La diaspora, instrument de la politique de puissance et de rayonnement de l’I... 1 La diaspora, instrument de la politique de puissance et de rayonnement de l’Inde à l’île Maurice et dans le monde Anouck Carsignol-Singh Introduction 1 L’utilisation par l’Inde des instruments classiques de la puissance étatique tels que la force nucléaire ou la pression économique ne doit pas occulter l’importance de la politique de Soft Power, adoptée dès le début du XXth siècle par les leaders nationalistes indiens et qui caractérise la politique étrangère du pays aujourd’hui encore. La diaspora, principal instrument du rayonnement culturel et politique de l’Inde à l’étranger au cours de la première moitié du XXe siècle, a été délaissée au lendemain de l’Indépendance par le gouvernement et la société indienne post-coloniale et n’a été réhabilitée que récemment. -

List of Associations, Centres and Clubs for Unesco 4040

As of November 2020 LIST OF ASSOCIATIONS, CENTRES AND CLUBS FOR UNESCO * 4040 TOTAL / 77 Member States * Breakdown by regions: 1744 Clubs in 15 APA MSs, 1719 Clubs in 22 AFR MSs, 463 Clubs in 26 ENA MSs (3 NatComs are currently reviewing Clubs’ accreditation), 77 Clubs in 10 ARB MSs, 37 Clubs in 4 LAC MSs. The List will be continuously evolving and updated as necessary. Contents ALGERIA – 3 TOTAL......................................................................................................................................... 5 ANGOLA – 1 TOTAL ........................................................................................................................................ 5 ARMENIA – 9 TOTAL ....................................................................................................................................... 5 AUSTRALIA – 1 TOTAL .................................................................................................................................... 6 AUSTRIA – 2 TOTAL ........................................................................................................................................ 6 AZERBAIJAN – 5 TOTAL ................................................................................................................................... 6 BELARUS – 56 TOTAL ...................................................................................................................................... 7 BELGIUM (FLANDERS) – 1 TOTAL ................................................................................................................. -

Life on Sugar Estates in Colonial Mauritius

Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 11-20 ISSN 2334-2420 (Print) 2334-2439 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jaa.v6n2a2 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jaa.v6n2a2 Life on Sugar Estates in Colonial Mauritius Mrs Rashila Vigneshwari Ramchurn1 Abstract This research paper seeks to examine life of descendants of indentured labourers on sugar estates in Mauritius. Attempt will be made to unravel gender disparity in all its forms. This study demonstrates how the bourgeoisie exploited and dominated the proletariat and preserved the status quo from the Marxist perspective as well as other theoretical approaches. Empirical data has been collected by conducting qualitative research using the face to face unstructured interview with elders aged 70 years to 108 years in the Republic of Mauritius and critical analysis of speeches of the leader of the Mauritius Labour Party. Secondary data has also been employed through qualitative research. The interviews were recorded in the year 2016,2018 and 2018 on digital recorder, transcribed and translated in English. All of the researches have been carried out objectively in a systematic manner so as to erase any bias in the study conducted. 70% of modern Mauritians are descendants of the indentured labourers. 1.1. Introduction Mauritius is an island in the South West Indian Ocean. Four hundred years ago there was no indigenous population on the island. All the people in Mauritius are immigrants. Mauritius has known three waves of immigrants namely the Dutch, the French and the British.