University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCT Gazette, Weekly Issue No. 42, 2000

42/2000 19 Oct/oct 2000 PCT Gazette - Section III - Gazette du PCT 15475 SECTION III WEEKLY INDEXES INDEX HEBDOMADAIRES INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION NUMBERS AND CORRESPONDING INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATION NUMBERS NUMÉROS DES DEMANDES INTERNATIONALES ET NUMÉROS DE PUBLICATION INTERNATIONALE CORRESPONDANTS International International International International International International Application Publication Application Publication Application Publication Numbers Numbers Numbers Numbers Numbers Numbers Numéros des Numéros de Numéros des Numéros de Numéros des Numéros de demandes publication demandes publication demandes publication internationales internationale internationales internationale internationales internationale AT CA CZ PCT/AT00/00046 WO 00/62393 PCT/CA99/00330 WO 00/61824 PCT/CZ00/00020 WO 00/61419 PCT/AT00/00064 WO 00/61240 PCT/CA99/00840 WO 00/61209 PCT/CZ00/00023 WO 00/61645 PCT/AT00/00068 WO 00/61896 PCT/CA99/00892 WO 00/61154 PCT/CZ00/00024 WO 00/61408 PCT/AT00/00079 WO 00/61820 PCT/CA99/00893 WO 00/61155 PCT/AT00/00080 WO 00/61319 PCT/CA00/00076 WO 00/61189 DE PCT/AT00/00081 WO 00/61973 PCT/CA00/00219 WO 00/62144 PCT/DE99/01102 WO 00/62274 PCT/AT00/00082 WO 00/61032 PCT/CA00/00312 WO 00/60983 PCT/DE99/01153 WO 00/61486 PCT/AT00/00084 WO 00/62040 PCT/CA00/00336 WO 00/62396 PCT/DE00/00114 WO 00/61504 PCT/AT00/00085 WO 00/61403 PCT/CA00/00352 WO 00/61826 PCT/DE00/00410 WO 00/61933 PCT/AT00/00087 WO 00/61428 PCT/CA00/00358 WO 00/61618 PCT/DE00/00478 WO 00/62330 PCT/AT00/00090 WO 00/61170 PCT/CA00/00359 WO 00/60981 PCT/DE00/00505 -

Passing the Mantle: a New Leadership for Malaysia NO

ASIA PROGRAM SPECIAL REPORT NO. 116 SEPTEMBER 2003 INSIDE Passing the Mantle: BRIDGET WELSH Malaysia's Transition: A New Leadership for Malaysia Elite Contestation, Political Dilemmas and Incremental Change page 4 ABSTRACT: As Prime Minister Mohamad Mahathir prepares to step down after more than two decades in power, Malaysians are both anxious and hopeful. Bridget Welsh maintains that KARIM RASLAN the political succession has ushered in an era of shifting factions and political uncertainty,as indi- New Leadership, Heavy viduals vie for position in the post-Mahathir environment. Karim Raslan discusses the strengths Expectations and weaknesses of Mahathir’s hand-picked successor,Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. He maintains that Abdullah will do well at moderating the influence of Malaysia’s more radical Islamic leaders, but page 9 doubts whether the new prime minister can live up to the excessive expectations that the polit- ical transition has engendered. M. Bakri Musa expresses hope that Abdullah will succeed where M. BAKRI MUSA (in his view) Mahathir has failed. For example, he urges the new leadership to revise Malaysia’s Post-Mahathir three-decade affirmative action policy and to tackle the problem of corruption. Malaysia: Coasting Along page 13 Introduction All three experts in this Special Report emphasize continuity.All agree that basic gov- Amy McCreedy ernmental policies will not change much; for fter more than 22 years in power, example, Abdullah Badawi’s seemingly heartfelt Malaysia’s prime minister Mohamad pledges to address corruption will probably A Mahathir is stepping down. “I was founder in implementation.The contributors to taught by my mother that when I am in the this Report do predict that Abdullah will midst of enjoying my meal, I should stop eat- improve upon Mahathir in one area: moderat- ing,”he quipped, after his closing remarks to the ing the potentially destabilizing force of reli- UMNO party annual general assembly in June. -

Sadc Electoral Observation Mission to the Republic of Mauritius Statement by the Hon. Maite Nkoana-Mashabane (Mp) Minister of In

SADC ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS STATEMENT BY THE HON. MAITE NKOANA-MASHABANE (MP) MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND COOPERATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA AND HEAD OF THE SADC ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION TO THE 2014 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS, DELIVERED ON 11 DECEMBER 2014 Moka, Republic of Mauritius Mr. Abdool Rahman, Electoral Commissioner, Your Excellency, Dr Aminata Touré, Head of the African Union (AU) Election Observation Mission, Honourable Ellen Molekane, Deputy Minister of State Security of the Republic of South Africa, Ambassador Julius Tebello Metsing of the Kingdom of Lesotho, the incoming Chairperson and Ambassador Theresia Samaria of the Republic of Namibia, representing outgoing Chairperson of the SADC Organ Troika, respectively, Your Excellency, Ms. Emilie Mushobekwa, SADC Deputy Executive Secretary, Fellow Heads of International Electoral Observation Missions, High Commissioners, Ambassadors, and other Members of the Diplomatic Corps, Esteemed Leaders of Political Parties and Independent Candidates, Members of the Media and of Civil Society Organisations, 2 Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, We are gathered here this morning to share with you the preliminary findings of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Electoral Observation Mission (SEOM) to the National Assembly Elections in the Republic of Mauritius, held on 10 December 2014. We thank you for graciously honouring our invitation. Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, This year we have witnessed an unprecedented number of elections in the SADC region, in Malawi, South Africa, Mozambique, Botswana and Namibia. On Wednesday, 10 December, the people of Mauritius also participated in this festival of democracy. In January and February 2015, the Republic of Zambia and the Kingdom of Lesotho, will also go to the polls. -

Pm: Learn Good Moral Values

PM: LEARN GOOD MORAL VALUES By HOHAtZAO A RAHIM PETALING JAVA: A "get-rich-quick" cul• ture evolving in the country has damaged society^ moral and ethical values, Datuk Sen Dr Mahathir Mohamad said. This culture must be contained and this could be done through education, the Prime Minister said yesterday. "It must be done away with and replaced with one that gives priority to long-term gams." he said when opening the Sunway College and a waterpark. He said the alternative culture should also take into consideration society's interests over the indi• vidual's. While education would help, he said, emphasis must be given to instilling moral and ethical values in people's pursuit for higher education. Dr Mahathir added that the country did not want to produce people without values as when they gained knowledge, they could turn out to be "edu• cated criminals." "With the increasing rate of white-collar crime, we must instil good values through education. "No matter how progressive a society is, it may not be able to sustain itself if such values are not part of education," he said. Dr Mahathir added that not all parents and the public knew what was good or bad for society. Thus, the belief that parents would naturally inculcate ALL IN ONE... chairman Musa briefs Dr Mahathir on Bandar Sunway. — STARpic by ABDULLAH SUBIR moral and ethical values in children was not true. He also cautioned the people against being too contented with the peace and harmony among the country's multiraci^ society. "Malaysia is now an example to other multiracial countries on how peace and harmony can be achieved. -

Wilson, MI5 and the Rise of Thatcher Covert Operations in British Politics 1974-1978 Foreword

• Forward by Kevin McNamara MP • An Outline of the Contents • Preparing the ground • Military manoeuvres • Rumours of coups • The 'private armies' of 1974 re-examined • The National Association for Freedom • Destabilising the Wilson government 1974-76 • Marketing the dirt • Psy ops in Northern Ireland • The central role of MI5 • Conclusions • Appendix 1: ISC, FWF, IRD • Appendix 2: the Pinay Circle • Appendix 3: FARI & INTERDOC • Appendix 4: the Conflict Between MI5 and MI6 in Northern Ireland • Appendix 5: TARA • Appendix 6: Examples of political psy ops targets 1973/4 - non Army origin • Appendix 7 John Colin Wallace 1968-76 • Appendix 8: Biographies • Bibliography Introduction This is issue 11 of The Lobster, a magazine about parapolitics and intelligence activities. Details of subscription rates and previous issues are at the back. This is an atypical issue consisting of just one essay and various appendices which has been researched, written, typed, printed etc by the two of us in less than four months. Its shortcomings should be seen in that light. Brutally summarised, our thesis is this. Mrs Thatcher (and 'Thatcherism') grew out of a right-wing network in this country with extensive links to the military-intelligence establishment. Her rise to power was the climax of a long campaign by this network which included a protracted destabilisation campaign against the Liberal and Labour Parties - chiefly the Labour Party - during 1974-6. We are not offering a conspiracy theory about the rise of Mrs Thatcher, but we do think that the outlines of a concerted campaign to discredit the other parties, to engineer a right-wing leader of the Tory Party, and then a right-wing government, is visible. -

Sao Phải Lo Lắng!

THERAVĀDA (PHẬT GIÁO NGUYÊN THỦY ) K. SRI. DHAMMANANDA Pháp Minh Trịnh Đức Vinh dịch SAO PHẢI LO LẮNG! PHỤC VỤ ĐỂ HOÀN TOÀN, HOÀN TOÀN ĐỂ PHỤC VỤ NHÀ XUẤT BẢN HỒNG ĐỨC HỘI LUẬT GIA VIỆT NAM NHÀ XUẤT BẢN HỒNG ĐỨC Địa chỉ: 65 Tràng Thi, Quận Hoàn Kiếm, Hà Nội Tel: (04) 39260024 Fax: (04) 39260031 Email: [email protected] CÔNG TY CỔ PHẦN DOANH NGHIỆP XÃ HỘI SAMANTA 16 Dương Quảng Hàm, Cầu Giấy, Hà Nội Website: www.samanta.vn Công ty CP DNXH Samanta giữ bản quyền dịch tiếng Việt và sách chỉ được phát hành để tặng, phát miễn phí, không bán. Quý độc giả, tổ chức muốn in sách để tặng, phát miễn phí xin vui lòng liên hệ qua email: [email protected]/[email protected] Chịu trách nhiệm xuất bản: Giám đốc Bùi Việt Bắc Chịu trách nhiệm nội dung: Tổng biên tập Lý Bá Toàn Biên tập : Nguyễn Thế Vinh Hiệu chỉnh: Lê Thị Minh Hà Sửa bản in: Bảo Vi Thiết kế bìa: Jodric LLP. www.jodric.com In 5000 cuốn, khổ 14,5 x 20,5 cm tại Xí nghiệp in FAHASA 774 Trường Chinh, P. 15, Q. Tân Bình, Tp Hồ Chí Minh. Số ĐKNXB: .........Số QĐXB của NXB Hồng Đức: .....Cấp ngày .......... In xong và nộp lưu chiểu Quý I/2016. Mã số sách tiêu chuẩn quốc tế (ISBN): 967-9920-72-0 Nội dung Lời tri ân Lời giới thiệu Lời dẫn nhập PHẦN 1: LO LẮNG VÀ CÁC NGUỒN GỐC CỦA NÓ 30 Chương 1: Lo lắng và sợ hãi Nguyên nhân của lo lắng Sợ hãi và mê tín Lo lắng ảnh hưởng đến chúng ta như thế nào? 40 Chương 2: Các vấn đề của chúng ta Đối diện với khó khăn Phát triển lòng can đảm và sự hiểu biết Đặt vấn đề vào đúng bối cảnh 56 Chương 3: Tại sao chúng ta đau khổ Bản chất của -

Educational Provision for Young Prisoners: to Realize Rights Or to Rehabilitate?

EDUCATIONAL PROVISION FOR YOUNG PRISONERS: TO REALIZE RIGHTS OR TO REHABILITATE? A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rosfizah Md Taib School of Law, Brunel University August 2012 Abstract This thesis examines the extent to which, and the reasons why, the government of Malaysia provides educational opportunities for children and young people who are being detained in the closed (penal) institutions on orders under section 91 (1) (f) and section 97 of the Child Act, 2001. This thesis presents a detailed analysis of the driving factor(s) that motivate the government of Malaysia in formulating and implementing policy and law in regards to providing educational opportunities for such young people. The thesis, therefore, examines the conceptualization by the Malaysia Prisons Department of children‟s rights, particularly their rights to education and offender rehabilitation. Analysis reveals that, educational rights in Malaysia have such priority because education is seen generally as the way to socialize (all) young people and to improve human capital and economic potential in Malaysia. Consequently, rehabilitation in Malaysian penal institutions is conceptualized almost entirely as education. The thesis argues that the Malaysian government has been using children‟s rights to education and also offender rehabilitation to improve the process of socialization of young people in prisons institutions to enable them to contribute to the achievement of the national goals. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To My Beloved Late Parents, MD. TAIB JOHAN and MAIMUNAH AYOB, for Everything My Husband, ZULKIFLI YAHYA for All the Truly Love My only Son, AHMAD NABHAN HARRAZ ZULKIFLI for All the Sacrifices and Understanding My Dear Supervisor, Prof. -

Recall of Mps

House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Recall of MPs First Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 June 2012 HC 373 [incorporating HC 1758-i-iv, Session 2010-12] Published on 28 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider political and constitutional reform. Current membership Mr Graham Allen MP (Labour, Nottingham North) (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Andrew Griffiths MP (Conservative, Burton) Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour, Leeds North East) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Camarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Tristram Hunt MP (Labour, Stoke on Trent Central) Mrs Eleanor Laing MP (Conservative, Epping Forest) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Stephen Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Bristol West) Powers The Committee’s powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in Temporary Standing Order (Political and Constitutional Reform Committee). These are available on the Internet via http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmstords.htm. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/pcrc. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Libraries in West Malaysia and Singapore; a Short History

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 722 LI 003 461 AUTHOR Tee Edward Lim Huck TITLE Lib aries in West Malaysia and Slngap- e; A Sh History. INSTITUTION Malaya Univ., Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia). PUB DATE 70 NOTE 169p.;(210 References) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; History; *Libraries; Library Planning; *Library Services; Library Surveys IDENTIFIERS *Library Development; Singapore; West Malaysia ABSTRACT An attempt is made to trace the history of every major library in Malay and Singapore. Social and recreational club libraries are not included, and school libraries are not extensively covered. Although it is possible to trace the history of Malaysia's libraries back to the first millenium of the Christian era, there are few written records pre-dating World War II. The lack of documentation on the early periods of library history creates an emphasis on developments in the modern period. This is not out of order since it is only recently that libraries in West Malaysia and Singapore have been recognized as one of the important media of mass education. Lack of funds, failure to recognize the importance of libraries, and problems caused by the federal structure of gc,vernment are blamed for this delay in development. Hinderances to future development are the lack of trained librarians, problems of having to provide material in several different languages, and the lack of national bibliographies, union catalogs and lists of serials. (SJ) (NJ (NJ LIBR ARIES IN WEST MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE f=t a short history Edward Lirn Huck Tee B.A.HONS (MALAYA), F.L.A. -

Life on Sugar Estates in Colonial Mauritius

Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 1-10 ISSN 2334-2420 (Print) 2334-2439 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jaa.v6n2a1 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jaa.v6n2a1 Life on Sugar Estates in Colonial Mauritius Mrs Rashila Vigneshwari Ramchurn1 Abstract This research paper seeks to examine life of descendants of indentured labourers on sugar estates in Mauritius. Attempt will be made to unravel gender disparity in all its forms. This study demonstrates how the bourgeoisie exploited and dominated the proletariat and preserved the status quo from the Marxist perspective as well as other theoretical approaches. Empirical data has been collected by conducting qualitative research using the face to face unstructured interview with elders aged 70 years to 108 years in the Republic of Mauritius and critical analysis of speeches of the leader of the Mauritius Labour Party. Secondary data has also been employed through qualitative research. The interviews were recorded in the year 2016,2018 and 2018 on digital recorder, transcribed and translated in English. All of the researches have been carried out objectively in a systematic manner so as to erase any bias in the study conducted. 70% of modern Mauritians are descendants of the indentured labourers. 1.1. Introduction Mauritius is an island in the South West Indian Ocean. Four hundred years ago there was no indigenous population on the island. All the people in Mauritius are immigrants. Mauritius has known three waves of immigrants namely the Dutch, the French and the British. -

Unwind Mauritius Times Tuesday, July 13, 2021 13

66th Year -- No. 3694 Tuesday, July 13, 2021 www.mauritiustimes.com facebook.com/mauritius.times 18 Pages - ePaper MAURITIUS TIMES l “The talent of success is nothing more than doing what you can do, well”. -- Henry W. Longfellow ‘POCA states clearly that the Director of ICAC should not be under the direction or control of any other person... If he chooses to be subservient, it is not only his personal problem...’ By LEX + See Page 4-5 Accountability Global Minimum or Impunity? Corporate Tax Rate By Jan Arden + See Page 3 Five lessons on bringing truth back to politics from Britain's first female philosophy professor By Peter West, Durham University + See Page 2 By Anil Madan + See Page 5 Mauritius Times Tuesday, July 13, 2021 www.mauritiustimes.com Edit Page facebook.com/mauritius.times 2 The Conversation Economic Security, Five lessons on bringing truth back to politics Society’s Security from Britain’s first female n last Friday’s issue of this paper we published MT, in an article in l’express takes a position which an interview of Lord Meghnad Desai who counters the rosy picture that Lord Desai depicted philosophy professor requires no formal introduction to the Mauritian of the MIC. The article puts forth several arguments Ipublic, and who was Chairman of the Mauritius of a very technical nature, but the sum total is that Investment Corporation Ltd (MIC) - a creation of the things could have been done differently, so as to Bank of Mauritius set up in the context of the Covid- preserve financial soundness at the same time as 19 pandemic as its economic and social impacts meeting the objectives of supporting companies began to be felt. -

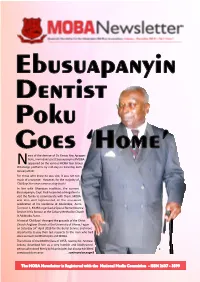

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc.