Copper in Horticulture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Diversity of Endophytic Fungi from Different Verticillium-Wilt-Resistant

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (2014), 24(9), 1149–1161 http://dx.doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1402.02035 Research Article Review jmb Diversity of Endophytic Fungi from Different Verticillium-Wilt-Resistant Gossypium hirsutum and Evaluation of Antifungal Activity Against Verticillium dahliae In Vitro Zhi-Fang Li†, Ling-Fei Wang†, Zi-Li Feng, Li-Hong Zhao, Yong-Qiang Shi, and He-Qin Zhu* State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Institute of Cotton Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Anyang, Henan 455000, P. R. China Received: February 18, 2014 Revised: May 16, 2014 Cotton plants were sampled and ranked according to their resistance to Verticillium wilt. In Accepted: May 16, 2014 total, 642 endophytic fungi isolates representing 27 genera were recovered from Gossypium hirsutum root, stem, and leaf tissues, but were not uniformly distributed. More endophytic fungi appeared in the leaf (391) compared with the root (140) and stem (111) sections. First published online However, no significant difference in the abundance of isolated endophytes was found among May 19, 2014 resistant cotton varieties. Alternaria exhibited the highest colonization frequency (7.9%), *Corresponding author followed by Acremonium (6.6%) and Penicillium (4.8%). Unlike tolerant varieties, resistant and Phone: +86-372-2562280; susceptible ones had similar endophytic fungal population compositions. In three Fax: +86-372-2562280; Verticillium-wilt-resistant cotton varieties, fungal endophytes from the genus Alternaria were E-mail: [email protected] most frequently isolated, followed by Gibberella and Penicillium. The maximum concentration † These authors contributed of dominant endophytic fungi was observed in leaf tissues (0.1797). The evenness of stem equally to this work. -

Integrated Pest Management: Current and Future Strategies

Integrated Pest Management: Current and Future Strategies Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa, USA Printed in the United States of America Cover design by Lynn Ekblad, Different Angles, Ames, Iowa Graphics and layout by Richard Beachler, Instructional Technology Center, Iowa State University, Ames ISBN 1-887383-23-9 ISSN 0194-4088 06 05 04 03 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging–in–Publication Data Integrated Pest Management: Current and Future Strategies. p. cm. -- (Task force report, ISSN 0194-4088 ; no. 140) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-887383-23-9 (alk. paper) 1. Pests--Integrated control. I. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology. II. Series: Task force report (Council for Agricultural Science and Technology) ; no. 140. SB950.I4573 2003 632'.9--dc21 2003006389 Task Force Report No. 140 June 2003 Council for Agricultural Science and Technology Ames, Iowa, USA Task Force Members Kenneth R. Barker (Chair), Department of Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh Esther Day, American Farmland Trust, DeKalb, Illinois Timothy J. Gibb, Department of Entomology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana Maud A. Hinchee, ArborGen, Summerville, South Carolina Nancy C. Hinkle, Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, Athens Barry J. Jacobsen, Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology, Montana State University, Bozeman James Knight, Department of Animal and Range Science, Montana State University, Bozeman Kenneth A. Langeland, Department of Agronomy, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Gainesville Evan Nebeker, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State David A. Rosenberger, Plant Pathology Department, Cornell University–Hudson Valley Laboratory, High- land, New York Donald P. -

Asparagus Pests and Diseases by Joan Allen

Asparagus Pests and Diseases By Joan Allen Asparagus is one of the few perennial vegetables and with good care a planting can produce a nice crop for 10-15 years. Part of that good care is keeping pest and disease problems under control. Letting them go can lead to weak plants and poor production, even death of the plants in some cases. Stress due to poor nutrition, drought or other problems can make the plants more susceptible to some diseases too. Because of this, good cultural practices, including a good site for new plantings, are the first step in preventing problems. After that, monitor regularly for common pests and diseases so you can catch any problems early and hopefully prevent them from escalating. Weed control is important for a couple of reasons. One, weeds compete with the crop for water and nutrients. More importantly from a disease perspective, they reduce air flow around the plants or between rows and this results in the asparagus spears or foliage remaining wet for a longer period of time after a rain or irrigation event. This matters because moisture promotes many plant diseases. This article will cover some of the most common pests and diseases of asparagus. If you’re not sure what you’ve got, I’ll finish up with resources for assistance. Insect pests include the common and spotted asparagus beetles, asparagus aphid, cutworms, and Japanese beetles. Diseases that will be covered are Fusarium diseases, rust, and purple spot. Both the common and spotted asparagus beetles (CAB and SAB respectively) overwinter in brushy or wooded areas near the field or garden as adults. -

Extension Plant Pathology Update July 2013

Extension Plant Pathology Update July 2013 Volume 1, Number 6 Edited by Jean Williams-Woodward Plant Disease Clinic Report for June 2013 By Ansuya Jogi and Jean Williams-Woodward The following tables consist of the commercial and homeowner samples submitted to the UGA plant disease clinics in Athens and Tifton for June 2013 (Table 1) and for one year ago in July 2012 (Table 2). The wet weather has been great for plant growth, as well as plant diseases. Various root rots, leaf spots and rusts have been diagnosed on almost all crops. The incidence of bacterial diseases will increase through July, as will Sclerotium rolfsii and Rhizoctonia diseases. We also continue to confirm Rose Rosette-associated virus on Knock-Out rose samples. Also, Dr. Little has confirmed Cucurbit Yellow Vine Disease on squash, caused by the bacterium, Serratia marcescens. She has a graduate student working on this disease and wants to know if you are seeing it. See page 7 for her summary of cucurbit diseases, including cucurbit yellow vine disease. Looking ahead with the current weather pattern, we expect to see more leaf and root diseases on all crops. This isn’t a surprise. Warm days, cooler nights, high humidity, wet foliage and saturated soils are the recipe for plant disease development. Again, it is an exciting time to be a plant pathologist. Table 1: Plant disease clinic sample diagnoses made in June 2013 Sample Diagnosis Host Plant Commercial Sample Homeowner Sample Apple Bitter Rot (Glomerella cingulata) Alternaria Leaf Spot Alternaria sp.) Rust (Gymnosporangium sp.) Assorted Fruits Insect Damage, Unidentified Insect Nutrient Imbalance; Abiotic Banana Shrub Insect Damage, Unidentified Insect Environmental Stress; Abiotic Beans Root Problems, Abiotic disorder Bentgrass Anthracnose (Colletotrichum cereale) Colletotrichum sp./spp. -

212Asparagus Workshop Part1.Indd

Plant Protection Quarterly Vol.21(2) 2006 63 National Asparagus Weeds Management Workshop Proceedings of a workshop convened by the National Asparagus Weeds Management Committee held in Adelaide on 10–11 November 2005. Editors: John G. Virtue and John K. Scott. Introduction John G. VirtueA and John K. ScottB A Department of Water Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide, South Australia 5001, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] B CSIRO Entomology, Private Bag 5, PO Wembley, Western Australia 6913, Australia. Welcome to this special issue of Plant Pro- The National Asparagus Weeds Man- authors for the effort they have put into tection Quarterly, which details the current agement Committee (NAWMC) convened their papers and all the workshop par- state of Asparagus weeds management in the National Asparagus Weeds Manage- ticipants for their contribution. A special Australia. Bridal creeper, Asparagus as- ment Workshop in Adelaide, 10–11 No- thanks for workshop organization also paragoides (L.) Druce, is the best known vember 2005. The workshop was attended goes to Dennis Gannaway and Susan Asparagus weed and certainly deserves by 60 people including representation ex- Lawrie. its Weed of National Signifi cance (WoNS) tending from South Africa, through most status in Australia. However, there are regions of continental Australia, to Lord Reference other Asparagus species in Australia that Howe Island in the Pacifi c. The workshop Agriculture & Resource Management have the potential to reach similar levels was made possible with funding assistance Council of Australia & New Zealand, of impact as bridal creeper on biodiversity through the Australian Government’s Nat- Australia & New Zealand Environment (and hence their inclusion in the national ural Heritage Trust. -

Evaluation of Certain Mineral Salts and Microelements Against Mango Powdery Mildew Under Egyptian Conditions

Journal of Phytopathology and Pest Management 3(3): 35-42, 2016 pISSN:2356-8577 eISSN: 2356-6507 Journal homepage: http://ppmj.net/ Evaluation of certain mineral salts and microelements against mango powdery mildew under Egyptian conditions Fatma A. Mostafa*, S. A. El Sharkawy Plant Pathology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. Abstract During the two successive seasons 2014 and 2015, three mineral salts used as commercial fertilizers (Potassium di -hydrogen orthophosphate, Potassium bicarbonate (85%), Calcium nitrate (17.1%)) and four microelements (Magnesium sulfate, Iron cheated (Fe-EDTA 6%), Zinc cheated (Zn-EDTA 12%), Manganese cheated (Mn-EDTA 12%)) were evaluated against powdery mildew of mango caused by Oidium mangiferea. Data obtained showed that all materials reduced significantly the disease severity percentage of mango powdery mildew disease comparing the control. Compared fungicides; Topsin M 70 (Thiophanate methyl) and Topas 10% (Penconazole) showed the most superior effect against the disease followed by potassium di-hydrogen orthophosphate. Tested microelements were arranged as zinc, iron and manganese, respectively due to their efficiency. Calcium nitrate and magnesium sulfate revealed the less effect. Evaluated microelements showed the higher efficacy than mineral fertilizers during the two experimental seasons except potassium monophosphate. While, two compared fungicides were the most efficiency to control the disease, tested materials reduced significantly the disease severity of mango powdery mildew disease and showed ability to reduce the number of required applications with conventional fungicides. Key words: Mango, powdery mildew, mineral salts, microelements, thiophonate methyl, penconazole. Copyright © 2016 ∗ Corresponding author: Fatma A. Mostafa, E-mail: [email protected] 35 Mostafa Fatma & El Sharkawy, 2016 Introduction addition, plant diseases play a limiting role in agricultural production. -

Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (Eds A

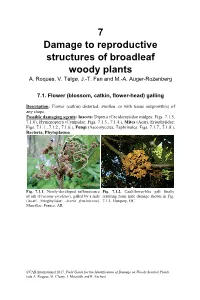

7 Damage to reproductive structures of broadleaf woody plants A. Roques, V. Talgø, J.-T. Fan and M.-A. Auger-Rozenberg 7.1. Flower (blossom, catkin, flower-head) galling Description: Flower (catkin) distorted, swollen, or with tissue outgrowth(s) of any shape. Possible damaging agents: Insects: Diptera (Cecidomyiidae midges: Figs. 7.1.5, 7.1.6), Hymenoptera (Cynipidae: Figs. 7.1.3., 7.1.4.), Mites (Acari, Eriophyiidae: Figs. 7.1.1., 7.1.2., 7.1.6.), Fungi (Ascomycetes, Taphrinales: Figs. 7.1.7., 7.1.8.), Bacteria, Phytoplasma. Fig. 7.1.1. Newly-developed inflorescence Fig. 7.1.2. Cauliflower-like gall finally of ash (Fraxinus excelsior), galled by a mite resulting from mite damage shown in Fig. (Acari, Eriophyiidae: Aceria fraxinivora). 7.1.1. Hungary, GC. Marcillac, France, AR. ©CAB International 2017. Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (eds A. Roques, M. Cleary, I. Matsiakh and R. Eschen) Damage to reproductive structures of broadleaf woody plants 71 Fig. 7.1.3. Berry-like gall on a male catkin Fig. 7.1.4. Male catkin of Quercus of oak (Quercus sp.) caused by a gall wasp myrtifoliae, deformed by a gall wasp (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Neuroterus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Callirhytis quercusbaccarum). Hungary, GC. myrtifoliae). Florida, USA, GC. Fig. 7.1.5. Inflorescence of birch (Betula sp.) Fig. 7.1.6. Symmetrically swollen catkin of deformed by a gall midge (Diptera, hazelnut (Corylus sp.) caused by a gall Cecidomyiidae: Semudobia betulae). midge (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae: Contarinia Hungary, GC. coryli) or a gall mite (Acari Eriophyiidae: Phyllocoptes coryli). -

Population Biology of Switchgrass Rust

POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) By GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology Escuela Politécnica del Ejército (ESPE) Quito, Ecuador 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2014 POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Thesis Approved: Dr. Stephen Marek Thesis Adviser Dr. Carla Garzon Dr. Robert M. Hunger ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their guidance and support, I express sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Marek, who has supported thought my thesis with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. One simply could not wish for a better or friendlier supervisor. I give special thanks to M.S. Maxwell Gilley (Mississippi State University), Dr. Bing Yang (Iowa State University), Arvid Boe (South Dakota State University) and Dr. Bingyu Zhao (Virginia State), for providing switchgrass rust samples used in this study and M.S. Andrea Payne, for her assistance during my writing process. I would like to recognize Patricia Garrido and Francisco Flores for their guidance, assistance, and friendship. To my family and friends for being always the support and energy I needed to follow my dreams. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Date of Degree: JULY, 2014 Title of Study: POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Major Field: ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT PATHOLOGY Abstract: Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial warm season grass native to a large portion of North America. -

Mangifera Indica L.) DEL BANCO DE GERMOPLASMA DEL INIA-CENIAP, MARACAY

Bioagro 28(3): 201-208. 2016 DIVERSIDAD DE HONGOS EN CINCO CULTIVARES DE MANGO (Mangifera indica L.) DEL BANCO DE GERMOPLASMA DEL INIA-CENIAP, MARACAY Carlos Pacheco1, María Suleima González2 y Edward Manzanilla2 RESUMEN El Campo Experimental del INIA-CENIAP, en Maracay, Venezuela, dispone de un banco de germoplasma con una elevada diversidad de cultivares de mango, pero en años recientes se ha detectado la muerte de gran cantidad de árboles en diferentes accesiones. Entre los factores asociados se encuentran la ocurrencia de enfermedades, particularmente las inducidas por hongos. Este trabajo tuvo como objetivo determinar la diversidad de hongos en hojas y ramas en los cultivares Criollo, Hadden, Hilacha, Kent y Tommy Atkins. Para cada cultivar se evaluaron cinco plantas y en cada árbol se tomaron al azar muestras de diez hojas provenientes de cinco ramas. Los hongos en sustrato natural fueron identificados por comparación de las estructuras de valor taxonómico, con la literatura especializada. Se registró la riqueza y se calcularon los índices de frecuencia, diversidad de Shannon-Wierner y de Margalef, equitatividad de Pielou y similaridad de Sorensen. La riqueza total resultó en 48 especies. El cultivar Kent presentó la mayor riqueza, y los más altos índices de diversidad y equitatividad. Los cultivares con mayor similaridad fueron Kent y Tommy Atkins. Se registran por primera vez Anopletis venezuelensis y Neofusicoccum mangiferae en hojas y N. parvum en ramas, asociado a muerte de éstas en mango. Palabras clave adicionales: Abundancia, equitatividad, índices de diversidad, Mangifera indica, riqueza, similaridad ABSTRACT Fungi diversity in five mango cultivars from germplasm bank of INIA-CENIAP, Maracay The experimental field of the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (CENIAP), INIA, Maracay, Venezuela, poses a germplasm bank, with a very high mango diversity, but lately, the death of several accessions has been detected. -

Disease and Insect Pests of Asparagus by William R

Page 1 Disease and insect pests of asparagus by William R. Morrison, III1, Sheila Linderman2, Mary K. Hausbeck2,3, Benjamin P. Werling3 and Zsofia Szendrei1,3 1MSU Department of Entomology; 2MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences; and 3Michigan State University Extension Extension Bulletin E3219 Introduction Biology • Fungus. The goal of this bulletin is to provide basic information • Sexual stage of the fungus (Pleospora herbarum) produc- needed to identify, understand and control insect and es overwintering structures (pseudothecia), appearing as disease pests of asparagus. Because each pest is different, small, black dots on asparagus plant debris from previous control strategies are most effective when they are tai- season. lored to the species present in your production fields. For this reason, this bulletin includes sections on pest identifi- • Pseudothecia release ascospores via rain splash and cation that show key characteristics and pictures to help wind, causing the primary infection for the new season. you determine which pests are present in your asparagus. • Primary infection progresses in the asexual stage of the It is also necessary to understand pests and diseases in fungus (Stemphylium vesicarium), which produces multiple order to appropriately manage them. This bulletin includes spores (conidia) cycles throughout the growing season. sections on the biology of each major insect and disease • Conidia enter plant tissue through wounds and stoma- pest. Finally, it also provides information on cultural and ta, which are pores of a plant used for respiration. general pest control strategies. For specifics on the pesti- • Premature defoliation of the fern limits photosynthetic cides available for chemical control of each pest, consult capability of the plant, decreasing carbohydrate reserves in MSU Extension bulletin E312, “Insect, Disease, and Nema- tode Control for Commercial Vegetables” (Order in the the crown for the following year’s crop. -

Symptoms: Pathogen Attacks the Inflorescence, Leaves, Stalk of In

IPM - SCHEDULE ON MANGO 1. Powdery mildew (Oidium mangiferae ) Symptoms: Pathogen attacks the inflorescence, leaves, stalk of inflorescence and young fruits with white superficial powdery growth of fungus resulting in its shedding. The sepals are relatively more susceptible than petals. The affected flowers fail to open and may fall prematurely (Fig 1). Dropping of unfertilized infected flowers leads to serious crop loss. Initially young fruits are covered entirely by the mildew. When fruit grows further, epidermis of the infected fruits cracks and corky tissues are formed. Fruits may remain on the tree until they reach up to marble size and then they drop prematurely (Fig 2 & 3.). Fig 1. Mildew on flowers Fig 2. Mildew on fruits / pedicel Fig 3. Necrotic lesions on shoulder Fig 4. Mildew on Lower Surface of and dropping from stalk end Leaf Infection is noticed on young leaves, when their colour changes from brown to light green. Young leaves are attacked on both the sides but it is more conspicuous on the grower surface. Often these patches coalesce and occupy larger areas turning into purplish brown in colour (Fig. 4). The pathogen is restricted to the area of the central and lateral veins of the infected leaf and often twists, curl and get distorted. Management • Prune diseased leaves and malformed panicles harbouring the pathogen to reduce primary inoculum load. • Spray wettable sulphur (0.2%) when panicles are 3-4” in size. • Spray dinocap (0.1%) 15-20 days after first spray. • Spray tridemorph (0.1%) 15-20 days after second spray. • Spraying at full bloom needs to be avoided.