Appendix 1 Talking Points for Ambassador Ortiz, April 10, 1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983

Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983 Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983 Edited by Nicole Phillip-Dowe and John Angus Martin Perspectives on the Grenada Revolution, 1979-1983 Edited by Nicole Phillip-Dowe and John Angus Martin This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Nicole Phillip-Dowe, John Angus Martin and contributors Book cover design by Hugh Whyte All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5178-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5178-7 CONTENTS Illustrations ................................................................................................ vii Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Abbreviations .............................................................................................. x Introduction ................................................................................................ xi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Citizens and Comrades in Arms: The Congruence of Fédon’s Rebellion and the Grenada -

Research, Repression, and Revolution— on Montreal and the Black Radical Tradition: an Interview with David Austin

THE CLR JAMES JOURNAL 20:1-2, Fall 2014 197-232 doi: 10.5840/clrjames201492319 Research, Repression, and Revolution— On Montreal and the Black Radical Tradition: An Interview with David Austin Peter James Hudson " ll roads lead to Montreal" is the title of an essay of yours on Black Montreal in the 1960s published in the Journal of African American History. But can you describe the road that led you to both Montreal and to the historical and theoretical work that you have done on the city over the past decades. A little intellectual biography . I first arrived in Montreal from London, England in 1980 with my brother to join my family. (We had been living with my maternal grandmother in London.) I was almost ten years old and spent two years in Montreal before moving to Toronto. I went to junior high school and high school in Toronto, but Montreal was always a part of my consciousness and we would visit the city on occasion, and I also used to play a lot of basketball so I traveled to Montreal once or twice for basketball tournaments. As a high school student I would frequent a bookstore called Third World Books and Crafts and it was there that I first discovered Walter Rodney's The Groundings with My Brothers. Three chapters in that book were based on presentations delivered by Rodney in Montreal during and after the Congress of Black Writers. So that was my first indication that something unique had happened in Montreal. My older brother Andrew was a college student at the time in Toronto and one day he handed me a book entitled Let the Niggers Burn! The Sir George Williams Affair and its Caribbean Aftermath, edited by Denis Forsythe. -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

I No Mas Vietnams! ^ Sodalistas: EUA Fuera De Centroamerica ^ Acto En NY Contra Ocupacion De Granada

Vol. 8, No. 21 12 de noviembre de 1984 UNA REVISTA SOCIALISTA DESTINADA A DEFENDER LOS INTERESES DEL PUEBLO TRABAJADOR I No mas Vietnams! ^ Sodalistas: EUA fuera de Centroamerica ^ Acto en NY contra ocupacion de Granada Lou HowortlPerspectiva Mundial NUEVA YORK—Setecientos manifestantes marcharon el 27 de octubre por las calles de Brooklyn —donde vive una de las concen- traciones mas grandes de afronorteamericanos y afrocaribenos en Estados Unidos— en protesta contra la Invasion y continua ocu pacion militar norteamericana de Granada. Los manifestantes tambien exigieron el cese Inmediato de la intervencidn militar norte- americana en Centroamerica y el Caribe. Igualmente denunciaron el arresto dos dias antes de Dessima Williams, quien fuera em- bajadora del gobierno revolucionario de Granada ante la Organizacion de Estados Americanos. Wiliiams, quien iba a ser ia oradora principal de la protesta, fue arrestada en Washington, D.C. por agentes del Servicio de Inmigracion y Naturalizacion, y acusada de estar ilegalmente en el pais. Una amplia gama de organizaciones politicas, comunitarias, afronorteamericanas y de solidaridad or- ganizaron la accion. uestra America Mujeres hondurenas: victimas de la guerra norteamericana Por Lee Martindale pagan una tarifa mensual al comandante del batallon local del ejercito hondurefio, lo cual les ampara de la intervencion policial. Una noticia publicada en El Diario/La Prensa el 30 de julio, y titula- "'Si una mujer que no pertenece al burdel pasea por el distrito, la po- do "Honduras: Crece la prostitucion en ambiente militar" relata la si- licfa la mete en un establecimiento porque asume que trabaja afuera del guiente historia: sistema', indico. -

The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287) Editor Virginia 22903-1781

f- THE ARMY Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet The Legal Basis for United 27-60-148 States Military Action April 1986 in Grenada Table of Contents Major Thomas J. Romig The Legal Basis for United States Instructor, International Law Division, Military Action in Grenada 1 TJAGSA Preventive Law and Automated Data "The Marshal said that over two decades Processing Acquisitions 16 ago, there was only Cuba in Latin Amer ica, today there are Nicaragua, Grenada, The Advocacy Section 21 and a serious battle is going on in El Sal vados. "I Trial Counsel Forum 21 "Thank God they came. If someone had not come inand done something, I hesitate The Advocate 40 to say what the situation in Grenada would be now. 'JZ Automation Developments 58 I. Introduction Criminal Law Notes 60 During the early morning hours of 25 October 1983, an assault force spearheaded by US Navy Legal Assistance Items 61 'Memorandum of Conversation between Soviet Army Chief Professional Responsibility Opinion 84-2 67 of General Staff Marshal Nikolai V.Ogarkov and Grenadian Army Chief of Staff Einstein Louison, who was then in the t Regulatory Law Item 68 Soviet Union for training, on 10 March 1983, 9uoted in Preface lo Grmactn: A Preliminary Rqorl, released by the Departments of State and Defense (Dec. 16, 1983) [here j CLE News 68 inafter cited as Preliminary Report]. 'Statement by Alister Hughes, a Grenadian journalist im- Current Material of Interest 72 Drisoned by the militaryjunta.. on 19 October 1983, after he was released by US Military Forces, qctolrd in N.Y. -

Challenges to CARIFORUM Labour, Private Sector and Employers - Final Evaluation

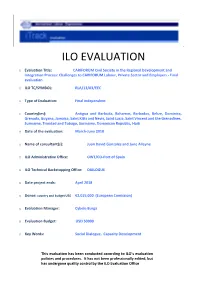

ILO EVALUATION o Evaluation Title: CARIFORUM Civil Society in the Regional Development and Integration Process: Challenges to CARIFORUM Labour, Private Sector and Employers - Final evaluation o ILO TC/SYMBOL: RLA/13/03/EEC o Type of Evaluation: Final independent o Country(ies): Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, Dominican Republic, Haiti o Date of the evaluation: March-June 2018 o Name of consultant(s): Juan David Gonzales and June Alleyne o ILO Administrative Office: DWT/CO-Port of Spain o ILO Technical Backstopping Office: DIALOGUE o Date project ends: April 2018 o Donor: country and budget US$ €2,015,000 (European Comission) o Evaluation Manager: Cybele Burga o Evaluation Budget: USD 50000 o Key Words: Social Dialogue, Capacity Development This evaluation has been conducted according to ILO’s evaluation policies and procedures. It has not been professionally edited, but has undergone quality control by the ILO Evaluation Office FINAL EVALUATION REPORT I Executive Summary Background and context In October 2008, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Dominican Republic, being members of the Forum of the Caribbean Group of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (CARIFORUM), signed the CARIFORUM-EU Economic Partnership Agreement -

February 2010 with Updates SJ.P65

February 2010 (Revised Edition) Decent work a priority for Belize Government launches region’s second Decent Work Country Programme The Government of Belize officially October, 2009. The launch follows Trade Union Congress and other launched the region’s second Decent Cabinet’s approval of the Programme on stakeholders, at a national workshop Work Country Programme on 29 14 July 2009. By concluding a Decent convened on 26-28 January 2009, in Work Country Programme (DWCP), the collaboration with the ILO. The Belize Government commits to working with the DWCP will focus on the following three social partners and priority areas: other stakeholders to (i) modernization and promote the Decent harmonization of Work Agenda in their national labour national development legislation in line with strategies. international labour The International Labour The Decent Work standards and Organization (ILO) is the United Agenda focuses on CARICOM Model Nations agency devoted to ways in which creating Labour Laws; advancing opportunities for women jobs, while promoting (ii) improvement of and men to obtain decent and respect for rights, skills and employability productive work in conditions of social protection, and (particularly for women freedom, equity, security and consensus-building and youth) and the human dignity. through social development of a Its main aims are to promote rights dialogue, can be made supportive labour at work, encourage decent central to social and market information employment opportunities, enhance economic system; and social protection and strengthen development. (iii)institutional dialogue in handling work-related issues. The DWCP was strengthening of the developed by the The Hon. Gabriel A. Martinez, social partners. -

A Love Affalr Turned Sour

GRENADA: A LOVE AFFALR TURNED SOUR: THE 1983 US INVASION OF GRENADA AM) ITS AFTERMATH BEVERLEY A, SPENCER A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Studies m conformity with the requirements for the degree of Maaer of Arts Queen' s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada January, 1998 copyright Q Beverley A. Spencer, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 191 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librv of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicrofoq vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'aiiteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fi-om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Canada ABSTRAC'I' October 25, 1983, the day that armed forces led by the United States invaded Grenada, signalled the end of four anà a half years of revolution. Grenadians commonly feel that October 19, 1983, the day ~henPrime hlinister Maurice Bishop aied alongside some parliamentarians, union officials and other supporters, really marked the end of the revolution. -

The 1983 Invasion of Grenada

ESSAI Volume 7 Article 36 4-1-2010 The 1983 nI vasion of Grenada Phuong Nguyen College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Nguyen, Phuong (2009) "The 1983 nI vasion of Grenada," ESSAI: Vol. 7, Article 36. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol7/iss1/36 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nguyen: The 1983 Invasion of Grenada The 1983 Invasion of Grenada by Phuong Nguyen (History 1140) he Invasion of Grenada in 1983, also known as Operation Urgent Fury, is a brief military operation that was heralded as a great triumph by some and harshly criticized by others. TAlthough the Invasion of Grenada is infrequently discussed today in modern politics, possibly due to the brevity and minimal casualties, it provides valuable insight into the way foreign policy was conducted under the Reagan administration towards the end of the Cold War. The invasion did not enjoy unanimous support, and the lessons of Grenada can be applied to the global problems of today. In order to understand why the United States intervened in Grenada, one must know the background of this small country and the tumultuous history of Grenadian politics, which led to American involvement. Grenada is the smallest of the Windward Islands of the Caribbean Sea, located 1,500 miles from Key West, Florida, with a population of 91,000 in 1983 and a total area of a mere 220 square miles (Stewart 5). -

Presidents of Latin American States Since 1900

Presidents of Latin American States since 1900 ARGENTINA IX9X-1904 Gen Julio Argentino Roca Elite co-option (PN) IlJ04-06 Manuel A. Quintana (PN) do. IlJ06-1O Jose Figueroa Alcorta (PN) Vice-President 1910-14 Roque Saenz Pena (PN) Elite co-option 1914--16 Victorino de la Plaza (PN) Vice-President 1916-22 Hipolito Yrigoyen (UCR) Election 1922-28 Marcelo Torcuato de Alv~ar Radical co-option: election (UCR) 1928--30 Hipolito Yrigoyen (UCR) Election 1930-32 Jose Felix Uriburu Military coup 1932-38 Agustin P. Justo (Can) Elite co-option 1938-40 Roberto M. Ortiz (Con) Elite co-option 1940-43 Ramon F. Castillo (Con) Vice-President: acting 1940- 42; then succeeded on resignation of President lune5-71943 Gen. Arturo P. Rawson Military coup 1943-44 Gen. Pedro P. Ramirez Military co-option 1944-46 Gen. Edelmiro J. Farrell Military co-option 1946-55 Col. Juan D. Peron Election 1955 Gen. Eduardo Lonardi Military coup 1955-58 Gen. Pedro Eugenio Military co-option Aramburu 1958--62 Arturo Frondizi (UCR-I) Election 1962--63 Jose Marfa Guido Military coup: President of Senate 1963--66 Dr Arturo IIIia (UCRP) Election 1966-70 Gen. Juan Carlos Onganfa Military coup June 8--14 1970 Adm. Pedro Gnavi Military coup 1970--71 Brig-Gen. Roberto M. Military co-option Levingston Mar22-241971 Junta Military co-option 1971-73 Gen. Alejandro Lanusse Military co-option 1973 Hector Campora (PJ) Election 1973-74 Lt-Gen. Juan D. Peron (PJ) Peronist co-option and election 1974--76 Marfa Estela (Isabel) Martinez Vice-President; death of de Peron (PJ) President Mar24--291976 Junta Military coup 1976-81 Gen. -

La Verdad Sobre Cuba Y Granada "Miestra America Llamado De Patriotas Salvadorenos a Los Pueblos Del Mundo

Vol. 7, No. 23 28 de noviembre de 1983 Ina REVISTA SOCIALISTA OESTINADA a defender LOS intereses del pueblo trabajador I I X V ■ > ■ 25 mil personas marchan en Washington el 12 de noviembre contra la intervendon en Centroamerica y el Caribe.(Foto: Roberto Kopec) La verdad sobre Cuba y Granada "Miestra America Llamado de patriotas salvadorenos a los pueblos del mundo [A continuacion publicamos extractos de un comunicado de la Co- Haremos morder el polvo de la derrota a los invasores. mandancia General del Frente Farabundo Marti para la Liberacion Na- El FMLN y el Frente Democratico Revolucionario son una amplia cional de El Salvador(FMLN) emitido el 5 de noviembre de 1983.] alianza de las fuerzas de la democracia, la independencia nacional y el progreso social y juntos constituyen la mas grande y eficaz organizacion popular de toda la historia nacional. El Frente Farabundo Martf para la Abrumado por los contundentes golpes que el FMLN viene descar- Liberacion Nacional ha construido del seno del pueblo, y activamente gando sobre el ejercito tftere, especialmente diuante los ultimos dos me- apoyado por el pueblo, un nutrido ejercito que cuenta con una indestruc- ses, y cumpliendo indicaciones del gobiemo de los Estados Unidos, el tible moral combativa, con una clara y profiinda conciencia revolucio- Ministro de Defensa de la dictadura salvadorena. General Eugenio Vi- naria y patriotica, que ha sido templada en miles de combates, que cuen- des Casanova, solicito hace pocos dfas a los ejercitos de Honduras y ta con una alta capacidad militar como le consta a las desmoralizadas y Guatemala que invadan nuestro pals. -

PDF Download Ordering Independence the End of Empire

ORDERING INDEPENDENCE THE END OF EMPIRE IN THE ANGLOPHONE CARIBBEAN, 1947-69 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Spencer Mawby | 9780230278189 | | | | | Ordering Independence The End of Empire in the Anglophone Caribbean, 1947-69 1st edition PDF Book Small States in International Relations. Other English-speaking Territories. Island Studies Journal 1 1 , 43— Feeny, S. Aid: Understanding International Development Cooperation. Vincent and St. The Windward Islands Colony was unpopular as Barbados wished to retain its separate identity and ancient institutions, while the other colonies did not enjoy the association with Barbados but needed such an association for defence against French invasions until Since Gairy was on the judging panel, inevitably there were many accusations that the contest had been rigged. The Justices and Vestry assisted a Commissioner appointed by the Governor of Jamaica to administer the islands. However, other terms may also be used to specifically refer to these territories, such as "British overseas territories in the Caribbean", [2] "British Caribbean territories" [3] or the older term "British West Indies". The South-South international cooperation in Latin America and the Caribbean: a view from their progress and constraints towards a context of global crisis. Attempts at a federal colony like in the Leewards were always resisted. This sparked great unrest - so many buildings were set ablaze that the disturbances became known as the "red sky" days - and the British authorities had to call in military reinforcements to help regain control of the situation. Gairy also served as head of government in pre-independence Grenada as Chief Minister from to , and as Premier from to See, for example, A.