3. Mahia and Dhola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1/3/2018 31/3/2018 Hoshiarpur District Social Security Office

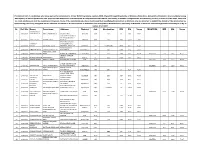

District Social Security Office Hoshiarpur MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Beneficiary Wise Sanction Report 1/3/2018 T o 31/3/2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.N PLA No. Beneficiary Name Father/Husband Name Amount --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- District Social Security Office Hoshiarpur MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Beneficiary Wise Sanction Report 1/3/2018 T o 31/3/2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.N PLA No. Beneficiary Name Father/Husband Name Amount --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Block/Panchayat/Village Name MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Scheme Name FADC 1 hsp/2017/r VEENA DEVI RAJINDER KUMAR 1,500 2 hsp/2017/r PREM LATA BALDEV SINGH 750 3 13630 BHOLI KARTAR SINGH 1,500 4 13629 PREM LATA VIJAY KUMAR 750 Scheme Name FADP 5 16605 HARJIT KAUR PREM LAL 750 6 9288 LISWA TARSEM MASIH 750 7 9507 RAMESH SINGH(CHANDNI) SANT SINGH 750 8 9496 RAKESH KUMAR BACHITER RAM 750 9 9505 KULDIP SINGH KIRPA RAM 750 10 9506 JIT KUMAR KAPOOR CHAND 750 11 2354 PREM LAL MANU 750 12 1749 SHAKTI KUMAR BASANTA RAM 750 Scheme Name FAWD 13 20473 PUSHPA DEVI SOHAN LAL 750 14 20475 RAM PIARI BALWARPAR SINGH 750 15 20471 RESHMA GULZAR 750 16 20472 SATYA DEVI JANAK RAJ 750 17 20743 KUSAM CHIB KIRSAN SINGH 750 18 20736 KAILASH DEVI AMAR SINGH 750 19 6447 PUSHPA DEVI -

The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020)

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020) Highlighted Yellow Have not yet submitted full papers for The Punjab: History and Culture (PHC) Highlighted Red were given conditional acceptance and have not submitted revised complete abstracts. Now they are requested to submit complete papers, immediately. Day 1: January 07, 2020 INAUGURAL SESSION 10:00 12:30 Lunch Break: 12:30-13:30 Parallel Session 1, Panel 1: The Punjab: From Antiquity to Modernity Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 From Vijayanagara to Maratha Empire: A Multi- Dr. Khushboo Kumari Linear Journey, c. 1500-1700 A. D. 2 13:40 – 13:50 On the Footsteps of Korean Buddhist monk in Dr. Esther Park Pakistan: Reviving the Sacred Ancient Trail of Gandhara 3 13:50 – 14:00 Archiving Porus Rafiullah Khan 4 14:00 – 14:10 Indus Valley Civilization, Harrapan Civilization and Kausar Parveen Khan the Punjab (Ancient Narratives) 5 14:10 – 14:20 Trade Relations of Indus Valley and Mesopotamian Dr. Irfan Ahmed Shaikh Civilizations: An Analytical Appraisal 6 14:20 – 14:30 Image of Guru Nanak : As Depicted in the Puratan Dr. Balwinderjit Kaur Janam Sakhi Bhatti 14:30 – 15:00 Discussion by Chair and Discussant Discussant Chair Moderator Parallel Session 1, Panel 2: The Punjab in Transition Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 History of ancient Punjab in the 6th century B. C Nighat Aslam with special reference of kingdom of Sivi and its Geographical division 2 13:40 – 13:50 Living Buddhists of Pakistan: An Ethnographic Aleena Shahid Study -

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Sample Page of Text

JPS: 11:2 Chaman & Sawyer: Imagining Life in a Punjabi Village Imagining Life in a Punjabi Village Saroj Chaman Punjabi University Patiala Caroline Sawyer State University of New York College at Old Westbury ______________________________________________________ This article explores the rhythms of traditional Punjabi village life: the ways that Punjabis set up their villages and dwellings and live their lives with a perception of the interrelatedness of the human, natural, and spiritual orders. The article looks at how they eat, celebrate their festivals and break the monotony of their challenging agrarian life style. The article also addresses the potential challenges that the “traditional” village has to deal with in the face of global change. ______________________________________________________ By nature, village activity transcends distinctions, synthesizing the natural and human orders; boundaries of work and play; perspectives of adults and children. Or rather, ideally, it does not synthesize these areas of life, but expresses an awareness of interrelationship that any number of subsequent developments have disrupted: urbanization, division of labor, industrialization, commercialization, globalization. Not least among these disrupting factors would be education and scholarly analysis. Once masses of people are taught to distinguish “high” from “popular” culture, possibilities for naïve production becomes much more restricted. When produced for external consumption— purchase or display outside the home environment—the intimate ties of an artifact to the cosmos, the dwelling, the functions it was intended to serve, and the artisan(s) become broken. The appreciation of folk art by outsiders thus signals the disruption of organicity. The buyer’s pursuit of the folk-artifact’s appeal and economic value; the twinge of the viewer on recognizing a quality she knows she is unable to produce; the urge of the scholar to describe and classify—all have something in common. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

E:\2019\Other Books\Final\Darshan S. Tatla\New Articles\Final Articles.Xps

EXPLORING ISSUES AND PROJECTS FOR COOPERATION BETWEEN EAST AND WEST PUNJAB WORLD PUNJABI CENTRE Monographs and Occasional Papers Series The World Punjabi Centre was established at Punjabi University, Patiala in 2004 at the initiative of two Chief Ministers of Punjabs of India and Pakistan. The main objective of this Centre is to bring together Punjabis across the globe on various common platforms, and promote cooperation across the Wagah border separating the two Punjabs of India and Pakistan. It was expected to have frequent exchange of scholarly meetings where common issues of Punjabi language, culture and trade could be worked out. This Monograph and Occasional Papers Series aims to highlight some of the issues which are either being explored at the Centre or to indicate their importance in promoting an appreciation and understanding of various concerns of Punjabis across the globe. It is hoped other scholars will contribute to this series from their respective different fields. Monographs 1. Exploring Possibilities of Cooperation among Punjabis in the Global Context – (Proceedings of the Conference held in 2006), Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 63pp. 2. Bhagat Singh and his Legend, (Papers Presented at the Conference in 2007) Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 280pp. Occasional Papers Series 1. Exploring Issues and Projects For Cooperation between East and West Punjab, Balkar Singh & Darshan S. Tatla, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. 1, 2019 2. Sikh Diaspora Archives: An Outline of the Project, Darshan S. Tatla & Balkar Singh, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. -

Handlooms in Madras State, Tamilndau

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME IX MADRAS PART XI-A HANDLOOMS IN MADRAS STATE P. K. NAMBIAR of the Indian Administrative Service Superintendent of Census Operations, Madras 1964 CENSUS OF INDIA, 1961 (Census Report-Vol. No. IX will relate to Madras only. Under this series will be issued the following publications) Part I-A General Report I-B Demography and Vital Statistics. I-C Subsidiary Tables .. Part II-A General Population Tables. II-B Economic Tables. II-C Cultural and Migration Taples. Part III Household Economic Tables. Part IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments. IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables. Part V-A Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Report & Tables). V-B Ethnographic notes on Scheduled Tribes. V-C Todas. V-D Ethnographic notes on Scheduled Castes. V-E Ethnographic notes on denotified and nomadic tribes. Part VI Village Survey Monographs (40 Nos.)' Part VII-A Crafts and Artisans. (9 Nos.) VII-B Fairs and Festivals. Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration } For official use only. VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation Part IX Atlas of the Madras State. Part X Madras City (2· Volumes) District Census Handbooks on twelve districts. Part XI Reports on Special Studies. A Handlooms in Madras State. B Food Habits in Madras State. C Slums of Madras City. D Temples of Madras State (5,Volumes). E Physically Handicapped of Madras State. F F'amily Planning Attitudes: A Survey. Part XU Languages of Madras State. As indicated in my Preface, tbis survey has been made possible by the experience and industry of Sri K. V. Sivasankaran whose earlier acquaintance with the working of the Co.-operative and Textile Departments has been of immeQse value. -

The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

THE MERCHANT CASTES OF A SMALL TOWN IN RAJASTHAN (a study of business organisation and ideology) CHRISTINE MARGARET COTTAM A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology and Soci ology, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. ProQuest Number: 10672862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Certain recent studies of South Asian entrepreneurial acti vity have suggested that customary social and cultural const raints have prevented positive response to economic develop ment programmes. Constraints including the conservative mentality of the traditional merchant castes, over-attention to custom, ritual and status and the prevalence of the joint family in management structures have been regarded as the main inhibitors of rational economic behaviour, leading to the conclusion that externally-directed development pro grammes cannot be successful without changes in ideology and behaviour. A focus upon the indigenous concepts of the traditional merchant castes of a market town in Rajasthan and their role in organising business behaviour, suggests that the social and cultural factors inhibiting positivejto a presen ted economic opportunity, stimulated in part by external, public sector agencies, are conversely responsible for the dynamism of private enterprise which attracted the attention of the concerned authorities. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

Name of Craftperson Address Phone No. Craft Award State 1 Abdul Kabir

Final List of SKMA - Craftspersons for 32nd Surajkund International Crafts Mela 2018 S. Name of Craftperson Address Phone No. Craft Award State No. 1 Abdul Kabir Parrey S/o Bun Makhama 9818312129, 9906410446 Embroidered J &K Ali Mohd. Parrey Tehsil Beerwah, items District Budgam, Kashmir, J & K 2 Adepu Ravi S/o Mogili Kothawada, 7702297658 Misc. Telangana Warangal, Telangana 3 Adil Shakeel Yatoo Kaka Sathu Nawab 9796505011 Cloths J&K Bazar, Srinanagr, J&K 4 Adil Shakeel Yatoo Kaka Sathu Nawab 9796505011 Cloths J&K Bazar, Srinanagr, J&K 5 Afzal Ahmad S/o Iqubal 65 Janta Flat, Sarai 9718187806 Leather Craft Delhi Ahmad Khakil, Sadar Bazar, Delhi 6 Ajay Kumar Bhardwaj Sarhaul, Gurgaon, 9811178079-089 Carpet & Haryana S/o Late R.P. Bhardwaj Haryana Furniture 7 Ajay Kumar Sahoo Harinakuli, Po 9266704096, 9015225735 Sea Shell State Award Odissa Arhaparti, Kamarda District Balasore, Odissa 8 Ajaz Ahmad Shah S/o M-19, 3rd Floor, 9911611361, 9469138520 Paper National Award Delhi Gh. Rasool Shah Batla House, Near Machie Khaliyalla Masjid, New Delhi 9 Akhilesh S/o Kalidas 4/16, Ramnagar Not Mentioned Misc. U.P. Kila, Varanasi, U.P. Page 1 of 39 Final List of SKMA - Craftspersons for 32nd Surajkund International Crafts Mela 2018 S. Name of Craftperson Address Phone No. Craft Award State No. 10 Akram Ansari S/o Siraj 2583, New Ramesh 9541170728 Embroidered Haryana Ansari Nagar, The Camp, & Crocheted Panipat Goods 11 Ali Hasan S/o Nanhe Khan A-107, Ravi Bihar, Kho 9460060459 Jewellery Rajasthan Nagoriyajan, Jaipur, Rajasthan 12 Altabali S/o Gulamnabi Salmakan, Khurja, U.P. -

A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, From

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Once Upon a Time in the Land of Five Rivers: A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, from Flora Annie Steel’s Colonial Collection to Shafi Aqeel’s Post-Partition Collection and Beyond A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in English Literature Massey University, Manawatu Campus, New Zealand Noor Fatima, 2019 i Abstract This thesis offers a critical analysis of two different collections of Punjabi folk tales which were collected at different moments in Punjab’s history: Tales of the Punjab (1894), collected by Flora Annie Steel and, Popular Folk Tales of the Punjab (2008) collected by Shafi Aqeel and translated from Urdu into English by Ahmad Bashir. The study claims that the changes evident in collections of Punjabi folk tales published in the last hundred years reveal the different social, political and ideological assumptions of the collectors, translators and the audiences for whom they were disseminated. Each of these collections have one prior edition that differs in important ways from the later one. Steel’s edition was first published during the late-colonial era in India as Wide- awake Stories in 1884 and consisted of tales that she translated from Punjabi into English. Aqeel’s first edition was collected shortly after the partition of India and Pakistan, as Punjabi Lok Kahaniyan in 1963 and consisted of tales he translated from Punjabi into Urdu. -

Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk Song of Rachna Valley

Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk song of Rachna Valley Fayyaz Baqir University of Gothenburg, Gothenberg, Sweden This paper is a reflection on a Punjabi love song from Rachna Valley. The theme of the song is true love, which symbolizes the courage to kiss death in the longing to find union with the beloved. This theme invariably depicts love as subversion of patriarchy. It is an act of union with the lover and renunciation of all the barriers of gender, caste and class. The lover in folk tradition—in contrast to the narrative of patriarchy—is invariably female. The story of love plays at various levels; it is negation of vanity, class, and discriminatory norms; and it affirms undying love that transcends all existing bonds. Union with the beloved who is an outcast and belongs to the territory of unknown is only possible by stepping out of the abode of known and living through the pain of separation from the paternal home. The paper provides an in-depth review of how separation from barriers is integrally linked with union with the lover. Love is not only a moment of union but is preceded by moment of separation that completes the dialectical transition from existence to being. Turn back, turn back, my wandering lover,1 turn your eyes to me again Turn back, haven’t I asked you to turn your eyes to me? Turn back (to meet me) in the back lanes of the majesty palaces, Turn back your eyes to me A chained tiger is in the lane, turn back (your eyes) to me A Police Chief has descended (on the lane), turn back (your eyes) to me He asks for my bracelets; turn back your eyes to me He asks for my necklace; turn back your eyes to me With laughter I gave him my bracelets, turn your eyes again to me With cries I gave him my necklace, turn back (my love) your eyes to me Turn back to me, my soul is sad, turn back your eyes to me my love Turn back to me, Turn back to me, my estranged lover.