Sample Page of Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 31 Social Significance of Religious Festivals

UNIT 31 SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF RELIGIOUS FESTIVALS structure 3 1.0 Objectives 3 1.1 Introduction 31.2 Scope of the Unit 32.2.1 What is a Religious Festival 32.2.2 Meaning of Social Significance 3 1.3 Some Religious Festivals 31.3.1 Sajhi 31.3.2 Kanva Chauth 31.3.3 Ravidar Jayanti 3 I .4 Social Significance : A Discussion 31.4.1 Adjustment Between Man, Nature and Society ' 3 1.4.2 Emotional Social Security of Individual 3 1.4.3 Identity, Solidarity, Differentiation and Conflict 3 1.4.4 Social Stratification 31.4.5 Ritual Art 31.4.6 Unity in Diversity 31.5 Let Us Sum Up 31.6 Key Words 3 1.7 Further Reading 3 1.8 Answers to Check Your Progress , 31.0 OBJECTIVES This unit seeks to help you to comprehend, sociologically, the phenomenon of religious festivals analyse its relation with individual, society and culture in general and in India in particular delineate its social significance, both positive and negative . enrich your overall understanding of the relation between Society and Religion. In this block we have so far covered three previous units on life cycle ritual (birth and marriage; and death) and a unit on pilgrimage. These units indicate that the social significance of religion pervades every aspect of our living right from birth onwards to marriage and death. It also pervades our ejforts at a better lge dtmd an attempt to come in contact with the sacred. This unit shows us a colourfi~lside of the significance of rituals. -

1/3/2018 31/3/2018 Hoshiarpur District Social Security Office

District Social Security Office Hoshiarpur MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Beneficiary Wise Sanction Report 1/3/2018 T o 31/3/2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.N PLA No. Beneficiary Name Father/Husband Name Amount --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- District Social Security Office Hoshiarpur MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Beneficiary Wise Sanction Report 1/3/2018 T o 31/3/2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.N PLA No. Beneficiary Name Father/Husband Name Amount --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Block/Panchayat/Village Name MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Scheme Name FADC 1 hsp/2017/r VEENA DEVI RAJINDER KUMAR 1,500 2 hsp/2017/r PREM LATA BALDEV SINGH 750 3 13630 BHOLI KARTAR SINGH 1,500 4 13629 PREM LATA VIJAY KUMAR 750 Scheme Name FADP 5 16605 HARJIT KAUR PREM LAL 750 6 9288 LISWA TARSEM MASIH 750 7 9507 RAMESH SINGH(CHANDNI) SANT SINGH 750 8 9496 RAKESH KUMAR BACHITER RAM 750 9 9505 KULDIP SINGH KIRPA RAM 750 10 9506 JIT KUMAR KAPOOR CHAND 750 11 2354 PREM LAL MANU 750 12 1749 SHAKTI KUMAR BASANTA RAM 750 Scheme Name FAWD 13 20473 PUSHPA DEVI SOHAN LAL 750 14 20475 RAM PIARI BALWARPAR SINGH 750 15 20471 RESHMA GULZAR 750 16 20472 SATYA DEVI JANAK RAJ 750 17 20743 KUSAM CHIB KIRSAN SINGH 750 18 20736 KAILASH DEVI AMAR SINGH 750 19 6447 PUSHPA DEVI -

Pros and Cons of Migration in Punjab

www.ijird.com March, 2015 Vol 4 Issue 3 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Pros and Cons of Migration in Punjab Kamaljit Rai Assistant Professor, Department of English, Mata Ganga Khalsa College for Girls, Manji Sahib, Kottan, Ludhiana, Punjab, India Abstract: In this paper I have discussed the pros and cons of migration from other states to Punjab. The problems faced by them, their rootlessness and the changing economic status of poor families in their hometowns are discussed with reference to the state of Punjab. The migrants go through teething troubles after coming to a new place, face a lot of sociological and psychological dilemmas which sometimes breaks them and sometimes saves them. The economic help which they send to their home state is used by them for development of their homes and families but the state in which they have migrated faces more crime, more illiteracy, more population and more problems of employment. The local population loses the job opportunities while the migrants grab the opportunity with both hands and are exploited by the rich landowners and industrialists and given low wages. They are subjected to inhuman and unhygienic conditions and are exploited physically, mentally, psychologically as well as sexually. 1. Introduction As defined by Lee, "Migration is permanent or semi-permanent change of residence". Migration has been the key word in modern history. Man has migrated from one place to another since ancient time. We too, as Aryans have migrated from far-off places to the fertile lands of Punjab. When a person changes a place of his residence it brings about lots of changes in his life. -

The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020)

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020) Highlighted Yellow Have not yet submitted full papers for The Punjab: History and Culture (PHC) Highlighted Red were given conditional acceptance and have not submitted revised complete abstracts. Now they are requested to submit complete papers, immediately. Day 1: January 07, 2020 INAUGURAL SESSION 10:00 12:30 Lunch Break: 12:30-13:30 Parallel Session 1, Panel 1: The Punjab: From Antiquity to Modernity Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 From Vijayanagara to Maratha Empire: A Multi- Dr. Khushboo Kumari Linear Journey, c. 1500-1700 A. D. 2 13:40 – 13:50 On the Footsteps of Korean Buddhist monk in Dr. Esther Park Pakistan: Reviving the Sacred Ancient Trail of Gandhara 3 13:50 – 14:00 Archiving Porus Rafiullah Khan 4 14:00 – 14:10 Indus Valley Civilization, Harrapan Civilization and Kausar Parveen Khan the Punjab (Ancient Narratives) 5 14:10 – 14:20 Trade Relations of Indus Valley and Mesopotamian Dr. Irfan Ahmed Shaikh Civilizations: An Analytical Appraisal 6 14:20 – 14:30 Image of Guru Nanak : As Depicted in the Puratan Dr. Balwinderjit Kaur Janam Sakhi Bhatti 14:30 – 15:00 Discussion by Chair and Discussant Discussant Chair Moderator Parallel Session 1, Panel 2: The Punjab in Transition Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 History of ancient Punjab in the 6th century B. C Nighat Aslam with special reference of kingdom of Sivi and its Geographical division 2 13:40 – 13:50 Living Buddhists of Pakistan: An Ethnographic Aleena Shahid Study -

E:\2019\Other Books\Final\Darshan S. Tatla\New Articles\Final Articles.Xps

EXPLORING ISSUES AND PROJECTS FOR COOPERATION BETWEEN EAST AND WEST PUNJAB WORLD PUNJABI CENTRE Monographs and Occasional Papers Series The World Punjabi Centre was established at Punjabi University, Patiala in 2004 at the initiative of two Chief Ministers of Punjabs of India and Pakistan. The main objective of this Centre is to bring together Punjabis across the globe on various common platforms, and promote cooperation across the Wagah border separating the two Punjabs of India and Pakistan. It was expected to have frequent exchange of scholarly meetings where common issues of Punjabi language, culture and trade could be worked out. This Monograph and Occasional Papers Series aims to highlight some of the issues which are either being explored at the Centre or to indicate their importance in promoting an appreciation and understanding of various concerns of Punjabis across the globe. It is hoped other scholars will contribute to this series from their respective different fields. Monographs 1. Exploring Possibilities of Cooperation among Punjabis in the Global Context – (Proceedings of the Conference held in 2006), Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 63pp. 2. Bhagat Singh and his Legend, (Papers Presented at the Conference in 2007) Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 280pp. Occasional Papers Series 1. Exploring Issues and Projects For Cooperation between East and West Punjab, Balkar Singh & Darshan S. Tatla, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. 1, 2019 2. Sikh Diaspora Archives: An Outline of the Project, Darshan S. Tatla & Balkar Singh, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. -

Handlooms in Madras State, Tamilndau

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME IX MADRAS PART XI-A HANDLOOMS IN MADRAS STATE P. K. NAMBIAR of the Indian Administrative Service Superintendent of Census Operations, Madras 1964 CENSUS OF INDIA, 1961 (Census Report-Vol. No. IX will relate to Madras only. Under this series will be issued the following publications) Part I-A General Report I-B Demography and Vital Statistics. I-C Subsidiary Tables .. Part II-A General Population Tables. II-B Economic Tables. II-C Cultural and Migration Taples. Part III Household Economic Tables. Part IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments. IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables. Part V-A Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Report & Tables). V-B Ethnographic notes on Scheduled Tribes. V-C Todas. V-D Ethnographic notes on Scheduled Castes. V-E Ethnographic notes on denotified and nomadic tribes. Part VI Village Survey Monographs (40 Nos.)' Part VII-A Crafts and Artisans. (9 Nos.) VII-B Fairs and Festivals. Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration } For official use only. VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation Part IX Atlas of the Madras State. Part X Madras City (2· Volumes) District Census Handbooks on twelve districts. Part XI Reports on Special Studies. A Handlooms in Madras State. B Food Habits in Madras State. C Slums of Madras City. D Temples of Madras State (5,Volumes). E Physically Handicapped of Madras State. F F'amily Planning Attitudes: A Survey. Part XU Languages of Madras State. As indicated in my Preface, tbis survey has been made possible by the experience and industry of Sri K. V. Sivasankaran whose earlier acquaintance with the working of the Co.-operative and Textile Departments has been of immeQse value. -

Government of Punjab

GOVERNMENT OF PUNJAB TELEPHONE DIRECTORY-2016 PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT (B&R) BR. CONTENTS Page No. PUNJAB RAJ BHAWAN 1 PUNJAB VIDHAN SABHA 1-2 PUNJAB & HARYANA HIGH COURT 2-5 CHIEF MINISTER OFFICE 5-8 DEPUTY CHIEF MINISTER OFFICE 8-9 CABINET MINISTERS 9-12 CHIEF PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARIES 12-14 LEADER OF OPPOSITION 14 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT FROM PUNJAB 15-17 MEMBERS OF PUNJAB LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 17-24 POLITICAL PARTIES IN PUNJAB VIDHAN SABHA 25 LOK PAL 25 CHIEF SECRETARY 25 ADVOCATE GENERAL 25 COMMISSIONS 26-32 FINANCIAL COMMISSIONERS/PRINCIPAL SECRETARIES 32-34 ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARIES 34-36 SPECIAL SECRETARIES 36-37 ADDITIONAL SECRETARIES 37-38 JOINT SECRETARIES 38-39 HEAD OF DEPARTMENTS 39-48 INFORMATION AND PUBLIC RELATIONS 48-51 POLICE DEPARTMENT 51-54 CORPORATIONS / BOARDS 55-68 COMMISSIONERS OF DIVISIONS 68 DEPUTY COMMISSIONERS 68-69 MAYORS & COMMISSIONERS OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS 69-70 CHAIRMAN DISTT. PLANNING COMMITTEE 71 UNIVERSITIES 72 PRESIDENT SECRETARIAT 73 VICE PRESIDENT SECRETARIAT 73 SUPREME COURT OF INDIA 73 ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA 73 NITI AAYOG 73 PRIME MINISTER OF INDIA 74 PARLIAMENT (RAJYA SABHA) 74 PARLIAMENT (LOK SABHA) 74 IAS & OTHER OFFICERS OF PB. POSTED AT DELHI 75 RESIDENT COMMISSIONER OFFICE AT NEW DELHI 76-77 CHANDIGARH ADMINISTRATION 77-78 OTHERS 78-80 PRESS, RADIO & TV 80-120 GUEST HOUSE/ENTERTAINMENT CENTRE (CHD) 120-121 CIRCUIT HOUSES IN PUNJAB & H.P. 121 EMERGENCY & GEN. UTILITY TEL. NO. AT CHD 121-123 SOME IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS AT DELHI 123-124 WEBSITES OF VARIOUS PUNJAB GOVT. DEPARTMENTS BOARDS, COPORATIONS, ETC. 124-125 OFFICIAL EMAIL ID’S OF THE DEPARTMENTS 125-132 STD CODES OF CITIES INDIA 138-143 *OEFY 1 Name & Designation Phone Residence Off. -

A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, From

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Once Upon a Time in the Land of Five Rivers: A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, from Flora Annie Steel’s Colonial Collection to Shafi Aqeel’s Post-Partition Collection and Beyond A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in English Literature Massey University, Manawatu Campus, New Zealand Noor Fatima, 2019 i Abstract This thesis offers a critical analysis of two different collections of Punjabi folk tales which were collected at different moments in Punjab’s history: Tales of the Punjab (1894), collected by Flora Annie Steel and, Popular Folk Tales of the Punjab (2008) collected by Shafi Aqeel and translated from Urdu into English by Ahmad Bashir. The study claims that the changes evident in collections of Punjabi folk tales published in the last hundred years reveal the different social, political and ideological assumptions of the collectors, translators and the audiences for whom they were disseminated. Each of these collections have one prior edition that differs in important ways from the later one. Steel’s edition was first published during the late-colonial era in India as Wide- awake Stories in 1884 and consisted of tales that she translated from Punjabi into English. Aqeel’s first edition was collected shortly after the partition of India and Pakistan, as Punjabi Lok Kahaniyan in 1963 and consisted of tales he translated from Punjabi into Urdu. -

Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk Song of Rachna Valley

Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk song of Rachna Valley Fayyaz Baqir University of Gothenburg, Gothenberg, Sweden This paper is a reflection on a Punjabi love song from Rachna Valley. The theme of the song is true love, which symbolizes the courage to kiss death in the longing to find union with the beloved. This theme invariably depicts love as subversion of patriarchy. It is an act of union with the lover and renunciation of all the barriers of gender, caste and class. The lover in folk tradition—in contrast to the narrative of patriarchy—is invariably female. The story of love plays at various levels; it is negation of vanity, class, and discriminatory norms; and it affirms undying love that transcends all existing bonds. Union with the beloved who is an outcast and belongs to the territory of unknown is only possible by stepping out of the abode of known and living through the pain of separation from the paternal home. The paper provides an in-depth review of how separation from barriers is integrally linked with union with the lover. Love is not only a moment of union but is preceded by moment of separation that completes the dialectical transition from existence to being. Turn back, turn back, my wandering lover,1 turn your eyes to me again Turn back, haven’t I asked you to turn your eyes to me? Turn back (to meet me) in the back lanes of the majesty palaces, Turn back your eyes to me A chained tiger is in the lane, turn back (your eyes) to me A Police Chief has descended (on the lane), turn back (your eyes) to me He asks for my bracelets; turn back your eyes to me He asks for my necklace; turn back your eyes to me With laughter I gave him my bracelets, turn your eyes again to me With cries I gave him my necklace, turn back (my love) your eyes to me Turn back to me, my soul is sad, turn back your eyes to me my love Turn back to me, Turn back to me, my estranged lover. -

NZCC – List of Documentary Films

NORTH ZONE CULTURAL CENTRE, PATIALA LIST OF DOCUMENTARY FILMS * S. Name of the Documented Directed by Year Total State / Format of Present Format Contents No. Film of Duration Venue recording making (at the time of making) 1. Kullu Dussehra SBM Pictures, 1993 20.13 Himachal U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DV D A documentary film on Annual New Delhi Pradesh International Dussehra Festival of Kullu 2. National Craft Fair SBM Pictures, 1994 29.33 Chandigarh U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary film on Food & New Delhi Craft Mela organized at Leisure Valley, Chandigarh 3. Lohri Festival at R epublic Day SBM Pictures, 1994 26.27 Delhi U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary film on Lohri Folk Dance Festival -1994 New Delhi Festival celebrated during Republic Day Camp at Delhi 4. Basant Darbar at Patiala Dr. Atamjit 1994 20.35 Patiala U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD Live coverage of Classical Singh Music and Singing Programme 5. Baisakhi Mela SBM Pictures, 1994 23.00 Delhi U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary fi lm on New Delhi Baisakhi Celebration at Ashoka Hotel, New Delhi 6. Maha M oorakh Semmellan SBM Pictures, 1994 20.40 Bharatpur U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD Live coverage of Hasya Kavi New Delhi Sammelan 7. Patiala Gharana SBM Pictures, 1994 20.00 Patiala U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary film on New Delhi Classical Music and Singing – Interview with Sh. Ajay Chakraborty * Record pertaining to the period before 1993 was irretrievably lost in the devastating floods in Patiala. -

Punjabi Folklore “Ballad”

Ad Litteram: An English Journal of International Literati ISSN: 2456 6624 December 2018: Volume 3 PUNJABI FOLKLORE “BALLAD” Sheeba Zafar* The term folk include all those persons living within a given area, who are conscious of a common cultural heritage, and have some common traits e.g. Occupation, languages and religion. The way of life of the group of the people is more traditional, more natural, less systematic and less specialized in comparison to the so called civilized people. The behavioral knowledge is based on oral tradition & not on written scriptures. The group have a sense of identity & belongingness regardless of its numerical strength. According to William Bascom , “folk lore means folk learning which comprehends all meaning that is transmitted by word of mouth and all crafts & techniques that are learnt by imitation or example, as well as the products of these crafts. Folk lore includes folk art folk crafts, folk costumes folk belief folk medicine, folk music, folk dance, folk games folk gestures.” It also includes folk literature with such forms as folk tales, Legends, Ballads, Myths, Epic lays, Proverbs & Riddles, culture, complex traditions & social beliefs. According to Malinowski & Radcliffe Brown-“folklore is a vital element in a living culture”. 197 *Assistant Professor, Al-Baha University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ad Litteram: An English Journal of International Literati ISSN: 2456 6624 December 2018: Volume 3 Folklorist Richard A. Waterman says, “Folklore is that art form, comprising various type of stories, proverbs, saying, spells, songs, incantations and many more things, which employs spoken language as its medium”. Charles Francis Potter in his definition states that Folklore is a lively fossil which refuses to die. -

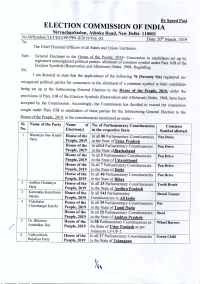

Allotment of Common Symbol Under 10B

By SpeedPost ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NirvachanSadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 No.56/SymboViLET/ECIIPP/PPS-II12019Nol._XI Date: 20th March, 2019 To, The Chief Electoral Officers of all States and Union Territories. Sub:- General Elections to the House of the People, 2019- Concession to candidates set up by registered unrecognized political parties- allotment of common symbol under Para lOB of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968- Regarding. Sir, I am directed to state that the applications of the following 76 (Seventy Six) registered un• recognized political parties for concession in the allotment of a common symbol to their candidates being set up at the forthcoming General Election to the House of the People, 2019, under the provisions of Para 10B of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, have been accepted by the Commission. Accordingly, the Commission has decided to extend the concession sought under Para 10B to candidates of these parties for the forthcoming General Election to the House of the People, 2019, in the constituencies mentioned as under: _ SI. Narne of the Party Name of No. of Parliamentary Constituencies Common No. Election(s) in the respective State Symbol allotted. 1 Bharatiya Nav Kranti House of the In all 80 Parliamentary Constituencies Pen Drive Party Peo_ple, 2019 in the State of Uttar Pradesh House of the In all14 Parliamentary Constituencies Pen Drive People, 2019 in the State ofJharkahand House of the In all 5 Parliamentary Constituencies Pen Drive People,