E:\2019\Other Books\Final\Darshan S. Tatla\New Articles\Final Articles.Xps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk 2016

Copyright by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk 2016 The Dissertation committee for Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Uncivilized language and aesthetic exclusion: Language, power and film production in Pakistan Committee: _____________________________ Craig Campbell, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Elizabeth Keating, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Kamran Ali _____________________________ Patience Epps _____________________________ Ali Khan _____________________________ Kathleen Stewart _____________________________ Anthony Webster Uncivilized language and aesthetic exclusion: Language, power and film production in Pakistan by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 To my parents Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible first and foremost without the kindness and generosity of the filmmakers I worked with at Evernew Studio. Parvez Rana, Hassan Askari, Z.A. Zulfi, Pappu Samrat, Syed Noor, Babar Butt, and literally everyone else I met in the film industry were welcoming and hospitable beyond what I ever could have hoped or imagined. The cast and crew of Sharabi, in particular, went above and beyond to facilitate my research and make sure I was at all times comfortable and safe and had answers to whatever stupid questions I was asking that day! Along with their kindness, I was privileged to witness their industry, creativity, and perseverance, and I will be eternally inspired by and grateful to them. My committee might seem large at seven members, but all of them have been incredibly helpful and supportive throughout my time in graduate school, and each of them have helped develop different dimensions of this work. -

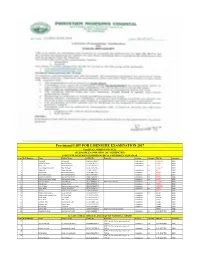

Provisional LIST for LISENSURE EXAMINATION 2017

Provisional LIST FOR LISENSURE EXAMINATION 2017 PAKISTAN NURSING COUNCIL LICENSURE EXAMINATION 2017 GENERIC BSN INSTITUTE OF NURSING KHYBER MEDICAL UNIVERSITY PESHAWAR Sr no Roll Number Name Father Name CNIC No. Remarks Centre Attempt DD No Amount 1 Irfanullah Rahmat Ali 15602-3994101-9 Isalamabad No 15435753 2000 2 Syed Afzal Shah Abdul Ghafoor 17101-1705973-7 Isalamabad 90635 2000 3 Afrooz Bibi Bakht Sherawan 15602-6846449-2 Isalamabad 1st 90636 2000 4 Shazad Aman-E-Room Sher Bahadar 15302-9095234-5 15086719 2000 5 Abbas Ali Khan Badshah 15306-3594812-1 Isalamabad 1st 90577 2000 6 Afzal Akber Muhammad Ishaq 15705-9827246-1 Islamabad 90638 2000 7 Muhammad Ayaz Muhammad Khitab 17301-5471894-1 Islamabad 1st 90575 2000 8 Muhammad Faizan Muhammad Sharif 17301-1655450-1 Islamabad 1st 90579 2000 9 Muhammad Uzair Akhtar Muhammad Akhtar 17301-5064391-1 Islamabad 1st 90576 2000 10 Parveen Akhtar Abdul Ghani 17101-5484531-4 Internship required Islamabad 1212582 2000 11 Riaz Ahmad Ahmad Sahib 15601-3703290-1 Islamabad 1st 90578 2000 12 Siraj-Ul-Haq Muhammad Anwar Shah 15303-9296087-5 Islamabad 15435757 2000 13 Wiqar Ullah Hassan Wali Khan 15701-3952070-7 Islamabad 1st 90573 2000 14 Shaista Muhammad Shah Khan 15605-0565468-6 99637 2000 15 Muhammad Zakaria Fazal Rahman 15302-9139655-5 Islamabad 1st 30729 2000 16 Muhammad Yaseen Khan Yar Min Khan 21201-4177450-5 Islamabad 30686 2000 17 Shah Faisal Taza Khan 21201-7956505-7 Islamabad 30694 2000 18 Shafi Ullah Sher Zada 15602-2637949-5 Islamabad 30687 2000 19 Tasleem Tahir Muhammad Tahir 15101-7887650-4 Islamabad 30690 2000 20 Naseem Bibi Bacha Zada 15101-1230463-0 Islamabad 30688 2000 21 Nusrat Bibi Sulaiman 15101-3072593-2 Islamabad 30689 2000 22 Sehrish Bibi Syed Rehmat Shah 13302-7576063-8 Original Internship required 30707 2000 23 Mumtaz Ali Khan Muhammad Shafiq 15601-0489893-7 Islamabad 1st C-04-2017-702 2000 ALLAMA IQBAL MEDICAL COLLEGE OF NURSING LAHORE S.NO Roll Number Name Father Name CNIC No. -

The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020)

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020) Highlighted Yellow Have not yet submitted full papers for The Punjab: History and Culture (PHC) Highlighted Red were given conditional acceptance and have not submitted revised complete abstracts. Now they are requested to submit complete papers, immediately. Day 1: January 07, 2020 INAUGURAL SESSION 10:00 12:30 Lunch Break: 12:30-13:30 Parallel Session 1, Panel 1: The Punjab: From Antiquity to Modernity Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 From Vijayanagara to Maratha Empire: A Multi- Dr. Khushboo Kumari Linear Journey, c. 1500-1700 A. D. 2 13:40 – 13:50 On the Footsteps of Korean Buddhist monk in Dr. Esther Park Pakistan: Reviving the Sacred Ancient Trail of Gandhara 3 13:50 – 14:00 Archiving Porus Rafiullah Khan 4 14:00 – 14:10 Indus Valley Civilization, Harrapan Civilization and Kausar Parveen Khan the Punjab (Ancient Narratives) 5 14:10 – 14:20 Trade Relations of Indus Valley and Mesopotamian Dr. Irfan Ahmed Shaikh Civilizations: An Analytical Appraisal 6 14:20 – 14:30 Image of Guru Nanak : As Depicted in the Puratan Dr. Balwinderjit Kaur Janam Sakhi Bhatti 14:30 – 15:00 Discussion by Chair and Discussant Discussant Chair Moderator Parallel Session 1, Panel 2: The Punjab in Transition Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 History of ancient Punjab in the 6th century B. C Nighat Aslam with special reference of kingdom of Sivi and its Geographical division 2 13:40 – 13:50 Living Buddhists of Pakistan: An Ethnographic Aleena Shahid Study -

New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab

Asia Society and CaravanSerai Present New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab Saturday, April 28, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 2 hours with no intermission New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan Performers Arooj Afab lead vocals Bhrigu Sahni acoustic guitar Jorn Bielfeldt percussion Arif Lohar lead vocals/chimta Qamar Abbas dholak Waqas Ali guitar Allah Ditta alghoza Shehzad Azim Ul Hassan dhol Shahid Kamal keyboard Nadeem Ul Hassan percussion/vocals Fozia vocals AROOJ AFTAB Arooj Aftab is a rising Pakistani-American vocalist who interprets mystcal Sufi poems and contemporizes the semi-classical musical traditions of Pakistan and India. Her music is reflective of thumri, a secular South Asian musical style colored by intricate ornamentation and romantic lyrics of love, loss, and longing. Arooj Aftab restyles the traditional music of her heritage for a sound that is minimalistic, contemplative, and delicate—a sound that she calls ―indigenous soul.‖ Accompanying her on guitar is Boston-based Bhrigu Sahni, a frequent collaborator, originally from India, and Jorn Bielfeldt on percussion. Arooj Aftab: vocals Bhrigu Sahni: guitar Jorn Bielfeldt: percussion Semi Classical Music This genre, classified in Pakistan and North India as light classical vocal music. Thumri and ghazal forms are at the core of the genre. Its primary theme is romantic — persuasive wooing, painful jealousy aroused by a philandering lover, pangs of separation, the ache of remembered pleasures, sweet anticipation of reunion, joyful union. Rooted in a sophisticated civilization that drew no line between eroticism and spirituality, this genre asserts a strong feminine identity in folk poetry laden with unabashed sensuality. -

LIST of PROGRAMMES Organized by SAHITYA AKADEMI During APRIL 1, 2016 to MARCH 31, 2017

LIST OF PROGRAMMES ORGANIZED BY SAHITYA AKADEMI DURING APRIL 1, 2016 TO MARCH 31, 2017 ANNU A L REOP R T 2016-2017 39 ASMITA Noted women writers 16 November 2016, Noted Bengali women writers New Delhi 25 April 2016, Kolkata Noted Odia women writers 25 November 2016, Noted Kashmiri women writers Sambalpur, Odisha 30 April 2016, Sopore, Kashmir Noted Manipuri women writers 28 November 2016, Noted Kashmiri women writers Imphal, Manipur 12 May 2016, Srinagar, Kashmir Noted Assamese women writers 18 December 2016, Noted Rajasthani women writers Duliajan, Assam 13 May 2016, Banswara, Rajasthan Noted Dogri women writers 3 March 2016, Noted Nepali women writers Jammu, J & K 28 May 2016, Kalimpong, West Bengal Noted Maithili women writers 18 March 2016, Noted Hindi women writers Jamshedpur, Jharkhand 30 June 2016, New Delhi AVISHKAR Noted Sanskrit women writers 04 July 2016, Sham Sagar New Delhi 28 March 2017, Jammu Noted Santali women writers Dr Nalini Joshi, Noted Singer 18 July 2016, 10 May, 2016, New Delhi Baripada, Odisha Swapan Gupta, Noted Singer and Tapati Noted Bodo women writers Gupta, Eminent Scholar 26 September 2016, 30 May, 2016, Kolkata Guwahati, Assam (Avishkar programmes organized as Noted Hindi women writers part of events are subsumed under those 26 September 2016, programmes) New Delhi 40 ANNU A L REOP R T 2016-2017 AWARDS Story Writing 12-17 November 2016, Jammu, J&K Translation Prize 4 August 2016, Imphal, Manipur Cultural ExCHANGE PROGRAMMES Bal Sahitya Puraskar 14 November 2016, Ahmedabad, Gujarat Visit of seven-member -

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

United Punjab: Exploring Composite Culture in a New Zealand Punjabi Film Documentary

sites: new series · vol 16 no 2 · 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11157/sites-id445 – article – SANJHA PUNJAB – UNITED PUNJAB: EXPLORING COMPOSITE CULTURE IN A NEW ZEALAND PUNJABI FILM DOCUMENTARY Teena J. Brown Pulu,1 Asim Mukhtar2 & Harminder Singh3 ABSTRACT This paper examines the second author’s positionality as the researcher and sto- ryteller of a PhD documentary film that will be shot in New Zealand, Pakistan, and North India. Adapting insights from writings on Punjab’s composite culture, the film will begin by framing the Christchurch massacre at two mosques on 15 March 2019 as an emotional trigger for bridging Punjabi migrant communi- ties in South Auckland, prompting them to reimagine a pre-partition setting of ‘Sanjha Punjab’ (United Punjab). Asim Mukhtar’s identity as a Punjabi Muslim from Pakistan connects him to the Punjabi Sikhs of North India. We use Asim’s words, experiences, and diary to explore how his insider role as a member of these communities positions him as the subject of his research. His subjectivity and identity then become sense-making tools for validating Sanjha Punjab as an enduring storyboard of Punjabi social memory and history that can be recorded in this documentary film. Keywords: united Punjab; composite culture; migrants; Punjabis; Pakistani; Muslims; Sikhs; South Auckland. INTRODUCTION The concept ‘Sanjha Punjab – United Punjab’ cuts across time, international and religious boundaries. On March 15, 2019, this image of a united Punjab inspired Pakistani Muslim Punjabis and Indian Sikh Punjabis to cooperate in support of Pakistani families caught in the terrorist attacks at Al Noor Masjid and Linwood Majid in Christchurch. -

Gurdial Singh: Messiah of the Marginalized

Gurdial Singh: Messiah of the Marginalized Rana Nayar Panjab University, Chandigarh In the past two months, Indian literature has lost two of its greatest writers; first it was the redoubtable Mahasweta Devi, who left us in July, and then it was the inimitable Gurdial Singh (August 18, 2016). Both these writers enjoyed a distinctive, pre-eminent position in their respective literary traditions, and both managed to transcend the narrow confines of the geographical regions within which they were born, lived or worked. Strangely enough, despite their personal, ideological, aesthetic and/or cultural differences, both worked tirelessly, all their lives, for restoring dignity, pride and self-respect to “the last man” on this earth. What is more, both went on to win the highest literary honor of India, the Jnanpeeth, for their singular contribution to their respective languages, or let me say, to the rich corpus of Indian Literature. Needless to say, the sudden departure of both these literary giants has created such a permanent vacuum in our literary circles that neither time nor circumstance may now be able to replenish it, ever. And it is, indeed, with a very heavy heart and tearful, misty eyes that I bid adieu to both these great writers, and also pray for the eternal peace of their souls. Of course, I could have used this opportunity to go into a comparative assessment of the works of both Mahasweta Devi and Gurdial Singh, too, but I shall abstain from doing so for obvious reasons. The main purpose of this essay, as the title clearly suggests, is to pay tribute to Gurdial Singh's life and work. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Sciences & Technology

Degree Year Of Student Selection Campus Department Title Study Full Name Father Name CNIC Degree Title CGPA Status Merit Status Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Khizra Khalil Khalil Ahmed Bajwa 6110152362736 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 ANAM ZHARA SYED AKHTER HUSSAIN SHAH 3740319867784 BS (Hons) 3.3 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 masood ur rehman Rehan shah 2140792271819 BS (Hons) 3.16 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Irfan Allah Dewaya 3220336130281 BS (Hons) 3.6 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Ahsan Iftikhar Iftikhar Ahmad 3720114487337 BS (Hons) 3.58 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Qurat Ul Ain Aziz Ullah Khan 3830101789040 BS (Hons) 3.18 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Majid Muhammad Faridoon 3740589951603 BS (Hons) 3.51 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Abdul Manan Muhammad Saleem 3740341694235 BS (Hons) 3.88 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Awais Muhammad Saeed 3710293250617 BS (Hons) 3.55 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 MAYA SYED SYED TAFAZUL HASSAN 6110194455878 BS (Hons) 3.7 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Mehreen Bibi Faqar Din 8220209594876 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 AMBREEN SAFDAR MALIK SAFDAR HUSSAIN 6110192701214 -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Dream and Reality

Chapter 1 Dream and Reality First of all whatever the circumstances, we should never be despondent. It is not always possible but that is the requirement for the job this manifesto seeks to accomplish. If anybody who loves to see Punjabi flourish finds the progress unsatisfactory, the reasons that come to my mind presently can be enumerated like general human weaknesses, burden of history and new distracting ideologies for the youth. In this respect, Pakistani Punjab is mired in apparently insurmountable difficulties. But as I have said that must not deter us. What to do, there is no escape as such are the jobs of those who dare to turn history’s course. And history gives us calm and patience if we listen to it, for example: ‘Early in 1839 nearly five hundred residents of Dacca in eastern Bengal petitioned the government in favour of Persian and against Bengali. The petitioners (of whom nearly two hundred were Hindus and most of the rest Muslims) used arguments practically identical to those of the British officials who had supported Persian in the recent inquiry: the Bengali script varied from place to place, one line of Persian could do the work of ten lines of Bengali, the awkward written style of Bengali read more slowly than that of Persian, people from one district could not understand the dialect of those from another, no previous government had ever kept records in Bengali, Persian had spread over a wide area and did not vary from place to place, people of all classes could understand Persian when read to them, and both Hindus and Muslims wanted to keep Persian.’ [Christopher R. -

SOHNI MAHIWAL Preserving South Asian Cultural Heritage Through Animated Storytelling

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 12-7-2017 SOHNI MAHIWAL Preserving South Asian Cultural Heritage Through Animated Storytelling Anem Syed Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Syed, Anem, "SOHNI MAHIWAL Preserving South Asian Cultural Heritage Through Animated Storytelling" (2017). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anem Syed SOHNI MAHIWAL Preserving South Asian Cultural Heritage Through Animated Storytelling By Anem Syed A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Visual Communication Design School of Design | College of Imaging Arts and Sciences Rochester Institute of Technology December 7, 2017 1 Anem Syed ABSTRACT Sohni Mahiwal: Preserving South Asian Cultural Heritage through Animated Storytelling By Anem Syed Majority of Pakistani youth is not enthralled by the country’s rich cultural heritage. There is less public knowledge on the subject. This translates into less appreciation or interest. The academic system is largely responsible for this. It imparts a conservative history of undivided India, focuses on politics, ignores its nuanced culture. Unless students venture into specialized fields of art and humanities, most do not get stimulated to study history. Additionally, today when digital learning is on the rise, there is a lack of relevant sources on the subject. This thesis is creating a digital source.