Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alphabetical List of Successful Candidates for Recruitment to the Posts of Building Inspector (Bs-14) on Contract Basis For

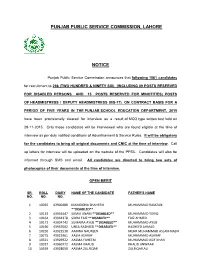

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE NOTICE Punjab Public Service Commission announces that following 1561 candidates for recruitment to 296 (TWO HUNDRED & NINETY SIX) (INCLUDING 09 POSTS RESERVED FOR DISABLED PERSONS AND 15 POSTS RESERVED FOR MINOTITIES) POSTS OF HEADMISTRESS / DEPUTY HEADMISTRESS (BS-17) ON CONTRACT BASIS FOR A PERIOD OF FIVE YEARS IN THE PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, 2015 have been provisionally cleared for interview as a result of MCQ type written test held on 29-11-2015. Only those candidates will be interviewed who are found eligible at the time of interview as per duly notified conditions of Advertisement & Service Rules. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring all original documents and CNIC at the time of interview. Call up letters for interview will be uploaded on the website of the PPSC. Candidates will also be informed through SMS and email. All candidates are directed to bring two sets of photocopies of their documents at the time of interview. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10065 43900486 MAMOONA SHAHEEN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN **DISABLED** 2 10133 43934447 SAMIA ANAM **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD TARIQ 3 10164 43944378 SIDRA FAIZ **DISABLED** FAIZ AHMED 4 10172 43904742 SUMAIRA AYUB **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD AYUB 5 10190 43937002 UNSA RASHEED **DISABLED** RASHEED AHMAD 6 10250 43923510 AAMNA NAUREEN MEHR MUHAMMAD ASLAM NASIR 7 10275 43922961 AASIA ASHRAF MUHAMMAD ASHRAF 8 10321 43926922 AASMA FAHEEM MUHAMMAD ASIF KHAN 9 10327 43960772 AASMA KHALID KHALID ANWAAR -

Energy Trade in South Asia Opportunities and Challenges

Energy Trade in South Asia in South Asia: Energy Trade Opportunities and Challenges The South Asia Regional Energy Study was completed as an important component of the regional technical assistance project Preparing the Energy Sector Dialogue and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation Energy Center Capacity Development. It involved examining regional energy trade opportunities among all the member states of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. The study provides interventions to improve regional energy cooperation in different timescales, including specific infrastructure projects which can be implemented during Opportunities and Challenges these periods. ENERGY TRADE IN SOUTH ASIA About the Asian Development Bank OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Sultan Hafeez Rahman Priyantha D. C. Wijayatunga Herath Gunatilake P. N. Fernando Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper. Printed in the Philippines ENERGY TRADE IN SOUTH ASIA OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES Sultan Hafeez Rahman Priyantha D. -

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

Tajdar E Haram Atif Aslam Dailymotion Mp3 Free Download

Tajdar e haram atif aslam dailymotion mp3 free download LINK TO DOWNLOAD · Coke Studio - Atif Aslam, Tajdar-e-Haram, Coke Studio Season 8, Coke Studio - Atif Aslam, Tajdar-e-Haram, Coke Studio Season 8, By Mera Pakistan. Mera Pakistan. Tajdar-e-Haram - Making Of Tajdar-e-Haram - Atif Aslam New Hamad. DailyHubs. Atif Aslam Tajdar e Haram Coke Studio Season 8 / aao madine chale by atif aslam. Just 4 Entertainment. Atif Aslam Tajdar-e. New Tajdar e Haram Download Mp3 Coke Studio Season 8 Atif Aslam Online With Full Lyrics Online Full Free Templates by BIGtheme NET renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Mp3 Songs Free Like Hindi Mp3 Songs, Punjabi Mp3 Songs, English Mp3 Songs, Pakistani Ost Mp3 Songs, Tamil Mp3 Songs, Telugu Mp3 Songs, 8D Mp3 Songs, 3D Mp3 Songs & Many More. Tajdar-e-Haram Naat With Lyrics By Atif Aslam - MP3 Download - Tajdar-e-haram ho nigahen karam, Ham ghareebon ke din bhi sanwar jayenge, Haamie-e-bekasan kya . Download New Mp3 Songs Mp3 Audio file type: MP3 kbps. Search. Tajdar E Haram Mp3 Download Songs Pk. Coke Studio Season 8 - Tajdar-e-Haram - Atif Aslam. PopBox. Play - Download. Tajdar E Haram Full Video | Satyameva Jayate | John Abraham | Manoj Bajpayee | Sajid Wajid. T-Series. Play - Download. Tajdar E Haram Lyrical Video | Satyameva Jayate | John Abraham | Manoj . Tajdar E Haram Ho Nigah Karam Mp3 Free. Here you'll download all the songs of Tajdar E Haram Ho Nigah Karam Mp3 Free for listen and reviews. Tajdar E Haram By Atif Aslam, Tajdar E Haram is an Islamic app designed for easy access for all users and sufiyanna kalaam Lovers to get this kalaam easily and also get all Islamic Naats and more. -

Book Review Essay Siren Song

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 6 Article 41 August 2020 Book Review Essay Siren Song Taimur Rahman Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rahman, Taimur (2020). Book Review Essay Siren Song. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(6), 516-519. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss6/41 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Siren Song1 Reviewed by Taimur Rahman2 The title of this book is extremely misleading. This is not a book about siren songs. Or perhaps it is, but not in the way you think. The book draws you in, dressed as a biography of prominent Pakistani female singers. And then, you find yourself trapped into a complex discussion of post-colonial philosophy stretching across time (in terms of philosophy) and space (in terms of continents). Hence, any review of this book cannot be a simple retelling of its contents but begs the reader to engage in some seriously strenuous thinking. I begin my review, therefore, not with what is in, but with what is not in the book - the debate that shapes the book, and to which this book is a stimulating response. -

Heer Ranjha Qissa Qawali by Zahoor Ahmad Mp3 Download

Heer ranjha qissa qawali by zahoor ahmad mp3 download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Look at most relevant Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru websites out of 15 at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Check th. Look at most relevant Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad websites out of Million at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Download Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video Video Music Download Music Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video, filetype:mp3 listen Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad. Download Heer Ranjha Part 1 Zahoor Ahmed Mp3, heer ranjha part 1 zahoor ahmed, malik shani, , PT30M6S, MB, ,, 2,, , , , download-heer- ranjha-partzahoor-ahmed-mp3, WOMUSIC, renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Planet Music Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad Mp3, Metrolagu Heer Ranjha. Home» Download zahoor ahmed maqbool ahmed qawwal heer ranjha part 1 play in 3GP MP4 FLV MP3 available in p, p, p, p video formats.. Heer ni ranjha jogi ho gaya - . · Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad - Duration: Khurram Rasheed , views. Heer is an extremely beautiful woman, born into a wealthy family of the Sial tribe in Jhang which is now Punjab, renuzap.podarokideal.ru (whose first name is Dheedo; Ranjha is the surname, his caste is Ranjha), a Jat of the Ranjha tribe, is the youngest of four brothers and lives in the village of Takht Hazara by the river renuzap.podarokideal.ru his father's favorite son, unlike his brothers who had to toil in. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Pop Compact Disc Releases - Updated 08/29/21

2011 UNIVERSITY AVENUE BERKELEY, CA 94704, USA TEL: 510.548.6220 www.shrimatis.com FAX: 510.548.1838 PRICES & TERMS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE NOW ACCEPTED INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE GENERALLY SHIPPED THRU THE U.S. POSTAL SERVICE. CHARGES VARY BY COUNTRY. WE WILL ALWAYS COMPARE VARIOUS METHODS OF SHIPMENT TO KEEP THE SHIPPING COST AS LOW AS POSSIBLE PAYMENT FOR ORDERS MUST BE MADE BY CREDIT CARD PLEASE NOTE - ALL ITEMS ARE LIMITED TO STOCK ON HAND POP COMPACT DISC RELEASES - UPDATED 08/29/21 Pop LABEL: AAROHI PRODUCTIONS $7.66 APCD 001 Rawals (Hitesh, Paras & Rupesh) "Pehli Nazar" / Pehli Nazar, Meri Nigahon Me, Aaja Aaja, Me Dil Hu, Tujhko Banaya, Tujhko Banaya (Sad), Humne Tumko, Oh Hasina, Me Tera Hu Diwana (ADD) LABEL: AUDIOREC $6.99 ARCD 2017 Shreeti "Mere Sapano Mein" (Music: Rajesh Tailor) Mere Sapano Mein, Jatey Jatey, Ek Khat, Teri Dosti, Jaan E Jaan, Tumhara Dil - 2 Versions, Shehenayi Ke Soor, Chalte Chalte, Instrumental (ADD) $6.99 ARCD 2082 Bali Brahmbhatt "Sparks of Love" / Karle Tu Reggae Reggae, O Sanam, Just Between You N Me, Mere Humdum, Jaana O Meri Jaana, Disco Ho Ya Reggae, Jhoom Jhoom Chak Chak, Pyar Ke Rang, Aag Ke Bina Dhuan Nahin, Ja Rahe Ho / Introducing Jayshree Gohil (ADD) LABEL: AVS MUSIC $3.99 AVS 001 Anamika "Kamaal Ho Gaya" / Kamaal Ho Gaya, Nach Lain De, Dhola Dhol, Badhai Ho Badhai, Beetiyan Kahaniyan, Aa Bhi Ja, Kahaan Le Gayee, You & Me LABEL: BMG CRESCENDO (BUDGET) $6.99 CD 40139 Keh Diya Pyar Se / Lucky Ali - O Sanam / Vikas Bhalla - Dhuan, Keh Diya Pyar Se / Anaida - -

Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author

1 Human Security Centre – Written evidence (AFG0019) Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author: Simon Schofield, Senior Fellow, In consultation with Rohullah Yakobi, Associate Fellow 2 1 Table of Contents 2. Executive Summary .............................................................................5 3. What is the Human Security Centre?.....................................................10 4. Geopolitics and National Interests and Agendas......................................11 Islamic Republic of Pakistan ...................................................................11 Historical Context...............................................................................11 Pakistan’s Strategy.............................................................................12 Support for the Taliban .......................................................................13 Afghanistan as a terrorist training camp ................................................16 Role of military aid .............................................................................17 Economic interests .............................................................................19 Conclusion – Pakistan .........................................................................19 Islamic Republic of Iran .........................................................................20 Historical context ...............................................................................20 Iranian Strategy ................................................................................23 -

O Khuda Full Video Song Mp4 Download

O khuda full video song mp4 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD O Khuda FULL VIDEO Song Amaal Mallik Hero Sooraj Pancholi Athiya Shetty TSeries download mp4, O Khuda FULL VIDEO Song Amaal O Khuda FULL VIDEO Song Amaal Mallik Hero Sooraj Pancholi Athiya Shetty ,ﻣﻮﺳﯿﻘﻰ Mallik Hero Sooraj Pancholi Athiya Shetty TSeries Download O Khuda Mp3 Song Download Ringtone mp3 dapat kamu download secara gratis di Metrolagu .ﺗﺤﻤﯿﻞ TSeries renuzap.podarokideal.ru melihat detail lagu O Khuda Mp3 Song Download Ringtone klik salah satu judul yang cocok, kemudian untuk link download O Khuda Mp3 Song Download Ringtone ada di halaman berikutnya. sekarang anda juga dapat mengunduh video O Khuda Mp3 Song Download Ringtone mp4. 8/24/ · O Khuda MP3 Song by Amaal Mallik from the movie Hero. Download O Khuda (ओ खदु ा) song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru and listen Hero O Khuda song offline. Download Wohi Khuda Hai Mp3 Song Download kbps mp3 dapat kamu download secara gratis di Metrolagu renuzap.podarokideal.ru melihat detail lagu Wohi Khuda Hai Mp3 Song Download kbps klik salah satu judul yang cocok, kemudian untuk link download Wohi Khuda Hai Mp3 Song Download kbps ada di halaman berikutnya. sekarang anda juga dapat mengunduh video Wohi Khuda Hai Mp3 Song Download kbps mp4. 1/29/ · Watch Ye Mat Kaho KHUDA Se-Download-From- [renuzap.podarokideal.ru] - Worldmag24 on Dailymotion. Search. Library. Log in. Sign up. Ye mat kaho khuda se best motivational renuzap.podarokideal.ru4. Motivation Hindi. Brahma Kumari Songs - Yeh Mat Kaho Khuda Se. little singer sweet voice #ye mat kaho kudha se song by little sweet singer. -

The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson's Poetry

International Academy Journal Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY THE MOTIVE OF ASCETICISM IN EMILY DICKENSON’S POETRY Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid, Ph.D. Odlar Yurdu University, Baku, Azerbaijan DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 25 November 2019 This paper is an attempt to analyze the poetry of Miss Emily Dickinson Accepted: 12 January 2020 (1830-1886) contributed both American and World literature in order to Published: 31 January 2020 reveal the extent of asceticism in it. Asceticism involves a deep, almost obsessive, concern with such problems as death, the life after death, the KEYWORDS existence of the soul, immortality, the existence of God and heaven, the meaningless of life and etc. Her enthusiastic expressions of life in poems spiritual asceticism, psychological had influenced the development of poetry and became the source of portrait, transcendentalism, Emily inspiration for other poets and poetesses not only in last century but also . Dickenson’s poetry in modern times. The paper clarifies the motives of spiritual asceticism, self-identity in Emily Dickenson’s poetry. Citation: Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. (2020) The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson’s Poetry. International Academy Journal Web of Scholar. 1(43). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 Copyright: © 2020 Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. -

Taajudin's Diary

Taajudin’s Diary Account of a Muslim author who accompanied Guru Nanak from Makkah to Baghdad By Sant Syed Prithipal Singh ne’ Mushtaq Hussain Shah (1902-1969) Edited & Translated By: Inderjit Singh Table of Contents Foreword................................................................................................. 7 When Guru Nanak Appeared on the World Scene ............................. 7 Guru Nanak’s Travel ............................................................................ 8 Guru Nanak’s Mission Was Outright Universal .................................. 9 The Book Story .................................................................................. 12 Acquaintance with Syed Prithipal Singh ....................................... 12 Discovery by Sardar Mangal Singh ................................................ 12 Professor Kulwant Singh’s Treatise ............................................... 13 Generosity of Mohinder Singh Bedi .............................................. 14 A Significant Book ............................................................................. 15 Recommendation ............................................................................. 16 Foreword - Sant Prithipal Singh ji Syed, My Father .............................. 18 ‘The Lion of the Lord took to the trade of the Fox’ – Translator’s Note .............................................................................................................. 20 About Me – Preface by Sant Syed Prithipal Singh ...............................