Book Review Essay Siren Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

Judicial Officers Interested for 1 Kanal Plots-Jalozai

JUDICIAL OFFICERS INTERESTED FOR 1 KANAL PLOTS‐JALOZAI S.No Emp_name Designation Working District 1 Mr. Anwar Ali District & Sessions Judge, Peshawar 2 Mr. Sharif Ahmad Member Inspection Team, Peshawar High Court, Peshawar 3 Mr. Ishtiaq Ahmad Administrative Judge, Accountability Courts, Peshawar 4 Syed Kamal Hussain Shah Judge, Anti‐Corruption (Central), Peshawar 5 Mr. Khawaja Wajih‐ud‐Din OSD, Peshawar High Court, Peshawar 6 Mr. Fazal Subhan Judge, Anti‐Terrorism Court, Abbottabad 7 Mr. Shahid Khan Administrative Judge, ATC Courts, Malakand Division, Dir Lower (Timergara) 8 Dr. Khurshid Iqbal Director General, KP Judicial Academy, Peshawar 9 Mr. Muhammad Younas Khan Judge, Anti‐Terrorism Court, Mardan 10 Mrs. Farah Jamshed Judge on Special Task, Peshawar 11 Mr. Inamullah Khan District & Sessions Judge, D.I.Khan 12 Mr. Muhammad Younis Judge on Special Task, Peshawar 13 Mr. Muhammad Adil Khan District & Sessions Judge, Swabi 14 Mr. Muhammad Hamid Mughal Member, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Service Tribunal, Peshawar 15 Mr. Shafiq Ahmad Tanoli OSD, Peshawar High Court, Peshawar 16 Mr. Babar Ali Khan Judge, Anti‐Terrorism Court, Bannu 17 Mr. Abdul Ghafoor Qureshi Judge, Special Ehtesab Court, Peshawar 18 Mr. Muhammad Tariq Chairman, Drug Court, Peshawar 19 Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan District & Sessions Judge, Hangu 20 Mr. Muhammad Iqbal Khan Judge on Special Task, Peshawar 21 Mr. Nasrullah Khan Gandapur District & Sessions Judge, Karak 22 Mr. Ikhtiar Khan District & Sessions Judge, Buner Relieved to join his new assingment as Judge, 23 Mr. Naveed Ahmad Khan Accountability Court‐IV, Peshawar 24 Mr. Ahmad Sultan Tareen District & Sessions Judge, Kohat 25 Mr. Gohar Rehman District & Sessions Judge, Dir Lower (Timergara) Additional Member Inspection Team, Secretariat for 26 Mr. -

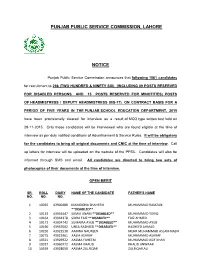

Alphabetical List of Successful Candidates for Recruitment to the Posts of Building Inspector (Bs-14) on Contract Basis For

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE NOTICE Punjab Public Service Commission announces that following 1561 candidates for recruitment to 296 (TWO HUNDRED & NINETY SIX) (INCLUDING 09 POSTS RESERVED FOR DISABLED PERSONS AND 15 POSTS RESERVED FOR MINOTITIES) POSTS OF HEADMISTRESS / DEPUTY HEADMISTRESS (BS-17) ON CONTRACT BASIS FOR A PERIOD OF FIVE YEARS IN THE PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, 2015 have been provisionally cleared for interview as a result of MCQ type written test held on 29-11-2015. Only those candidates will be interviewed who are found eligible at the time of interview as per duly notified conditions of Advertisement & Service Rules. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring all original documents and CNIC at the time of interview. Call up letters for interview will be uploaded on the website of the PPSC. Candidates will also be informed through SMS and email. All candidates are directed to bring two sets of photocopies of their documents at the time of interview. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10065 43900486 MAMOONA SHAHEEN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN **DISABLED** 2 10133 43934447 SAMIA ANAM **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD TARIQ 3 10164 43944378 SIDRA FAIZ **DISABLED** FAIZ AHMED 4 10172 43904742 SUMAIRA AYUB **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD AYUB 5 10190 43937002 UNSA RASHEED **DISABLED** RASHEED AHMAD 6 10250 43923510 AAMNA NAUREEN MEHR MUHAMMAD ASLAM NASIR 7 10275 43922961 AASIA ASHRAF MUHAMMAD ASHRAF 8 10321 43926922 AASMA FAHEEM MUHAMMAD ASIF KHAN 9 10327 43960772 AASMA KHALID KHALID ANWAAR -

'EMU' Nominated 'Global Cultural Ambassador' for Pakistan Souq

Wednesday, March 11, 2020 15 Reports by L N Mallick For events and press releases email [email protected] or L N Mallick Pakistan Prism L N Mallick call (974) 4000 2222 L N Mallick ‘EMU’ nominated ‘Global Cultural Ambassador’ for Pakistan Souq Syed Muhammad Imran Momina, alias ‘EMU’ of the legendary music band Fuzön, was awarded the ambassadorship at a ceremony attended by Pakistani community members, music enthusiasts, local singers and musicians YED Muhammad Imran Mo- mina, alias ‘EMU’ of the leg- endary music band Fuzön, was declared the Global Cultural Ambassador for Pakistan Souq Sin Doha recently. EMU visited Doha at the invitation of Pakistan Souq and was awarded the am- bassadorship in a ceremony attended by a large number of Pakistani community members, notables and influencers of the community, music enthusiasts, and local singers and musicians. Supported by Pakistan Embassy Qa- tar, Pakistan Souq is an online community platform created primarily for business purposes. It’s become very popular be- cause of its social, cultural and community- friendly activities. Its aim is to engage the Pakistani community in economic, social and cultural arenas. Syed Muhammad Imran Momina, alias EMU, poses EMU was accompanied by Pakistan Souq for picture in front of Tornado Tower in Doha. CEO Amir Saeed Khan to the event, which was graced by Pakistan Ambassador to Qatar HE Syed Ahsan Raza Shah and Commercial Secretary Salman Ali. The ambassador welcomed EMU in Doha and congratulated him on his nomination as Global Cultural Ambassador of music and showbiz for Pakistan Souq. Dr Khalil Ullah Shibli, who coordinated EMU’s Doha visit, said this honour is likely EMU with Pakistan Souq CEO Amir Saeed Khan (left) and Dr Khalil Ullah Shibli (right). -

Karakurum International University

Year Of Student Selection Campus Department Degree Title Study Full Name Father Name CNIC Degree Title CGPA Status Merit Status Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Huma Jehangir Shah Jehangir 7150202498060 BS (Hons) 3.99 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Misbah Ali Alidad 7150286262148 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Mehpara aftab Ghulam murtaza 7150403929262 BS (Hons) 3.53 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Arifa Nisar Nisar Hussain 7170205708304 BS (Hons) 3.41 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Sami Ullah Saraj Uddin 7150141920279 BS (Hons) 2.86 Not Selected Eligible but Low CGPA Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 kaynat Ali Ehsan Ali 7150133675356 BS (Hons) 2.88 Not Selected Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Sakina ali Sher Ali 7150188697616 BS (Hons) 3.08 Not Selected Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 1 Ahmad hussain wazir baig 7150159136583 BS (Hons) 2.94 Not Selected Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 2 Nusrat Zehra Ali MUhammad 7150161490355 BS (Hons) 3.06 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 2 Sonam Abbas Abbas Ali 7150181945484 BS (Hons) 2.8 Not Selected Eligible but Low CGPA Main campus Behavioral Sciences Bachelors 16 Years 4 salma nasir hussain 7150168456376 BS (Hons) 2.97 Not Selected -

Heer Ranjha Qissa Qawali by Zahoor Ahmad Mp3 Download

Heer ranjha qissa qawali by zahoor ahmad mp3 download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Look at most relevant Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru websites out of 15 at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Qawali heer ranjha zahoor renuzap.podarokideal.ru found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Check th. Look at most relevant Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad websites out of Million at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Heer ranjha mp3 qawali zahoor ahmad found at renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru, renuzap.podarokideal.ru and etc. Download Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video Video Music Download Music Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad Video, filetype:mp3 listen Kawali Heer Ranjha Zahoor Ahmad. Download Heer Ranjha Part 1 Zahoor Ahmed Mp3, heer ranjha part 1 zahoor ahmed, malik shani, , PT30M6S, MB, ,, 2,, , , , download-heer- ranjha-partzahoor-ahmed-mp3, WOMUSIC, renuzap.podarokideal.ru Download Planet Music Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad Mp3, Metrolagu Heer Ranjha. Home» Download zahoor ahmed maqbool ahmed qawwal heer ranjha part 1 play in 3GP MP4 FLV MP3 available in p, p, p, p video formats.. Heer ni ranjha jogi ho gaya - . · Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Qawali pharr wanjhli badal taqdeer ranjhna teri wanjhli ty lgi hoi heer ranjhna.. (punjabi spirtual ghazal by arif feroz khan) Heer Ranjha Full Qawwali By Zahoor Ahmad - Duration: Khurram Rasheed , views. Heer is an extremely beautiful woman, born into a wealthy family of the Sial tribe in Jhang which is now Punjab, renuzap.podarokideal.ru (whose first name is Dheedo; Ranjha is the surname, his caste is Ranjha), a Jat of the Ranjha tribe, is the youngest of four brothers and lives in the village of Takht Hazara by the river renuzap.podarokideal.ru his father's favorite son, unlike his brothers who had to toil in. -

Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There Were Few Women Painters in Colonial India

I. (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar Paper Coordinator Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Author Dr. Archana Verma Independent Scholar Content Reviewer (CR) Prof Rekha Pande University of Hyderabad Language Editor (LE) Prof. Sumita University of Allhabad Parmar (B) Description of Module Items Description of Module Subject Name Women’s Studies Paper Name Women and History Module Name/ Title, Women performers in colonial India description Module ID Paper- 3, Module-30 Pre-requisites None Objectives To explore the achievements of women performers in colonial period Keywords Indian art, women in performance, cinema and women, India cinema, Hindi cinema Women Performing Artists in Colonial India There were few women painters in Colonial India. But in the performing arts, especially acting, women artists were found in large numbers in this period. At first they acted on the stage in theatre groups. Later, with the coming of cinema, they began to act for the screen. Cinema gave them a channel for expressing their acting talent as no other medium had before. Apart from acting, some of them even began to direct films at this early stage in the history of Indian cinema. Thus, acting and film direction was not an exclusive arena of men where women were mostly subjects. It was an arena where women became the creators of this art form and they commanded a lot of fame, glory and money in this field. In this module, we will study about some of these women. Nati Binodini (1862-1941) Fig. 1 – Nati Binodini (get copyright for use – (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Binodini_dasi.jpg) Nati Binodini was a Calcutta based renowned actress, who began to act at the age of 12. -

Pop Compact Disc Releases - Updated 08/29/21

2011 UNIVERSITY AVENUE BERKELEY, CA 94704, USA TEL: 510.548.6220 www.shrimatis.com FAX: 510.548.1838 PRICES & TERMS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE NOW ACCEPTED INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE GENERALLY SHIPPED THRU THE U.S. POSTAL SERVICE. CHARGES VARY BY COUNTRY. WE WILL ALWAYS COMPARE VARIOUS METHODS OF SHIPMENT TO KEEP THE SHIPPING COST AS LOW AS POSSIBLE PAYMENT FOR ORDERS MUST BE MADE BY CREDIT CARD PLEASE NOTE - ALL ITEMS ARE LIMITED TO STOCK ON HAND POP COMPACT DISC RELEASES - UPDATED 08/29/21 Pop LABEL: AAROHI PRODUCTIONS $7.66 APCD 001 Rawals (Hitesh, Paras & Rupesh) "Pehli Nazar" / Pehli Nazar, Meri Nigahon Me, Aaja Aaja, Me Dil Hu, Tujhko Banaya, Tujhko Banaya (Sad), Humne Tumko, Oh Hasina, Me Tera Hu Diwana (ADD) LABEL: AUDIOREC $6.99 ARCD 2017 Shreeti "Mere Sapano Mein" (Music: Rajesh Tailor) Mere Sapano Mein, Jatey Jatey, Ek Khat, Teri Dosti, Jaan E Jaan, Tumhara Dil - 2 Versions, Shehenayi Ke Soor, Chalte Chalte, Instrumental (ADD) $6.99 ARCD 2082 Bali Brahmbhatt "Sparks of Love" / Karle Tu Reggae Reggae, O Sanam, Just Between You N Me, Mere Humdum, Jaana O Meri Jaana, Disco Ho Ya Reggae, Jhoom Jhoom Chak Chak, Pyar Ke Rang, Aag Ke Bina Dhuan Nahin, Ja Rahe Ho / Introducing Jayshree Gohil (ADD) LABEL: AVS MUSIC $3.99 AVS 001 Anamika "Kamaal Ho Gaya" / Kamaal Ho Gaya, Nach Lain De, Dhola Dhol, Badhai Ho Badhai, Beetiyan Kahaniyan, Aa Bhi Ja, Kahaan Le Gayee, You & Me LABEL: BMG CRESCENDO (BUDGET) $6.99 CD 40139 Keh Diya Pyar Se / Lucky Ali - O Sanam / Vikas Bhalla - Dhuan, Keh Diya Pyar Se / Anaida - -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Shah Hussain - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Shah Hussain - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Shah Hussain(1538–1599) Shah Hussain was a Punjabi Sufi poet who is regarded as a Sufi saint. He was the son of Sheikh Usman, a weaver, and belonged to the Dhudha clan of Rajputs. He was born in Lahore (present-day Pakistan). He is considered a pioneer of the Kafi form of Punjabi poetry. Shah Hussain's love for a Brahmin boy called "Madho" or "Madho Lal" is famous, and they are often referred to as a single person with the composite name of "Madho Lal Hussain". Madho's tomb lies next to Hussain's in the shrine. His tomb and shrine lies in Baghbanpura, adjacent to the Shalimar Gardens. His Urs (annual death anniversary) is celebrated at his shrine every year during the "Mela Chiraghan" ("Festival of Lights"). <b>Kafis of Shah Hussain</b> Hussain's poetry consists entirely of short poems known as Kafis. A typical Hussain Kafi contains a refrain and some rhymed lines. The number of rhymed lines is usually between four and ten. Only occasionally is a longer form adopted. Hussain's Kafis are also composed for, and have been set to, music deriving from Punjabi folk music. Many of his Kafis are part of the traditional Qawwali repertoire. His poems have been performed as songs by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Abida Parveen and Noor Jehan, among others. Here are three examples, which draw on the love story of Heer Ranjha: "Ni Mai menoon Khedeyan di gal naa aakh Ranjhan mera, main Ranjhan di, Khedeyan noon koodi jhak Lok janey Heer kamli hoi, Heeray da var chak" "Do not talk of the Khedas to me, mother. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Faizghar Newsletter

Issue: January Year: 2016 NEWSLETTER Content Faiz Ghar trip to Rana Luxury Resort .............................................. 3 Faiz International Festival ................................................................... 4 Children at FIF ............................................................................................. 11 Comments .................................................................................................... 13 Workshop on Thinking Skills ................................................................. 14 Capacity Building Training workshops at Faiz Ghar .................... 15 [Faiz Ghar Music Class tribute to Rasheed Attre .......................... 16 Faiz Ghar trip to [Rana Luxury Resort The Faiz Ghar yoga class visited the Rana Luxury Resort and Safari Park at Head Balloki on Sunday, 13th December, 2015. The trip started with live music on the tour bus by the Faiz Ghar music class. On reaching the venue, the group found a quiet spot and spread their yoga mats to attend a vigorous yoga session conducted by Yogi Sham- shad Haider. By the time the session ended, the cold had disappeared, and many had taken o their woollies. The time was ripe for a fruit eating session. The more sporty among the group started playing football and frisbee. By this time the musicians had got their act together. The live music and dance session that followed became livelier when a large group of school girls and their teachers joined in. After a lot of food for the soul, the group was ready to attack Gogay kay Chaney, home made koftas, organic salads, and the most delicious rabri kheer. The group then took a tour of the jungle and the safari park. They enjoyed the wonderful ambience of the bamboo jungle, and the ostriches, deers, parakeet, swans, and many other wild animals and birds. Some members also took rides on the train and colour- ful donkey carts.