Unit 31 Social Significance of Religious Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

1/3/2018 31/3/2018 Hoshiarpur District Social Security Office

District Social Security Office Hoshiarpur MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Beneficiary Wise Sanction Report 1/3/2018 T o 31/3/2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.N PLA No. Beneficiary Name Father/Husband Name Amount --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- District Social Security Office Hoshiarpur MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Beneficiary Wise Sanction Report 1/3/2018 T o 31/3/2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.N PLA No. Beneficiary Name Father/Husband Name Amount --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Block/Panchayat/Village Name MUKERIAN ABDULAPUR ABDULLAPUR Scheme Name FADC 1 hsp/2017/r VEENA DEVI RAJINDER KUMAR 1,500 2 hsp/2017/r PREM LATA BALDEV SINGH 750 3 13630 BHOLI KARTAR SINGH 1,500 4 13629 PREM LATA VIJAY KUMAR 750 Scheme Name FADP 5 16605 HARJIT KAUR PREM LAL 750 6 9288 LISWA TARSEM MASIH 750 7 9507 RAMESH SINGH(CHANDNI) SANT SINGH 750 8 9496 RAKESH KUMAR BACHITER RAM 750 9 9505 KULDIP SINGH KIRPA RAM 750 10 9506 JIT KUMAR KAPOOR CHAND 750 11 2354 PREM LAL MANU 750 12 1749 SHAKTI KUMAR BASANTA RAM 750 Scheme Name FAWD 13 20473 PUSHPA DEVI SOHAN LAL 750 14 20475 RAM PIARI BALWARPAR SINGH 750 15 20471 RESHMA GULZAR 750 16 20472 SATYA DEVI JANAK RAJ 750 17 20743 KUSAM CHIB KIRSAN SINGH 750 18 20736 KAILASH DEVI AMAR SINGH 750 19 6447 PUSHPA DEVI -

Pros and Cons of Migration in Punjab

www.ijird.com March, 2015 Vol 4 Issue 3 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) Pros and Cons of Migration in Punjab Kamaljit Rai Assistant Professor, Department of English, Mata Ganga Khalsa College for Girls, Manji Sahib, Kottan, Ludhiana, Punjab, India Abstract: In this paper I have discussed the pros and cons of migration from other states to Punjab. The problems faced by them, their rootlessness and the changing economic status of poor families in their hometowns are discussed with reference to the state of Punjab. The migrants go through teething troubles after coming to a new place, face a lot of sociological and psychological dilemmas which sometimes breaks them and sometimes saves them. The economic help which they send to their home state is used by them for development of their homes and families but the state in which they have migrated faces more crime, more illiteracy, more population and more problems of employment. The local population loses the job opportunities while the migrants grab the opportunity with both hands and are exploited by the rich landowners and industrialists and given low wages. They are subjected to inhuman and unhygienic conditions and are exploited physically, mentally, psychologically as well as sexually. 1. Introduction As defined by Lee, "Migration is permanent or semi-permanent change of residence". Migration has been the key word in modern history. Man has migrated from one place to another since ancient time. We too, as Aryans have migrated from far-off places to the fertile lands of Punjab. When a person changes a place of his residence it brings about lots of changes in his life. -

Sample Page of Text

JPS: 11:2 Chaman & Sawyer: Imagining Life in a Punjabi Village Imagining Life in a Punjabi Village Saroj Chaman Punjabi University Patiala Caroline Sawyer State University of New York College at Old Westbury ______________________________________________________ This article explores the rhythms of traditional Punjabi village life: the ways that Punjabis set up their villages and dwellings and live their lives with a perception of the interrelatedness of the human, natural, and spiritual orders. The article looks at how they eat, celebrate their festivals and break the monotony of their challenging agrarian life style. The article also addresses the potential challenges that the “traditional” village has to deal with in the face of global change. ______________________________________________________ By nature, village activity transcends distinctions, synthesizing the natural and human orders; boundaries of work and play; perspectives of adults and children. Or rather, ideally, it does not synthesize these areas of life, but expresses an awareness of interrelationship that any number of subsequent developments have disrupted: urbanization, division of labor, industrialization, commercialization, globalization. Not least among these disrupting factors would be education and scholarly analysis. Once masses of people are taught to distinguish “high” from “popular” culture, possibilities for naïve production becomes much more restricted. When produced for external consumption— purchase or display outside the home environment—the intimate ties of an artifact to the cosmos, the dwelling, the functions it was intended to serve, and the artisan(s) become broken. The appreciation of folk art by outsiders thus signals the disruption of organicity. The buyer’s pursuit of the folk-artifact’s appeal and economic value; the twinge of the viewer on recognizing a quality she knows she is unable to produce; the urge of the scholar to describe and classify—all have something in common. -

Government of Punjab

GOVERNMENT OF PUNJAB TELEPHONE DIRECTORY-2016 PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT (B&R) BR. CONTENTS Page No. PUNJAB RAJ BHAWAN 1 PUNJAB VIDHAN SABHA 1-2 PUNJAB & HARYANA HIGH COURT 2-5 CHIEF MINISTER OFFICE 5-8 DEPUTY CHIEF MINISTER OFFICE 8-9 CABINET MINISTERS 9-12 CHIEF PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARIES 12-14 LEADER OF OPPOSITION 14 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT FROM PUNJAB 15-17 MEMBERS OF PUNJAB LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 17-24 POLITICAL PARTIES IN PUNJAB VIDHAN SABHA 25 LOK PAL 25 CHIEF SECRETARY 25 ADVOCATE GENERAL 25 COMMISSIONS 26-32 FINANCIAL COMMISSIONERS/PRINCIPAL SECRETARIES 32-34 ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARIES 34-36 SPECIAL SECRETARIES 36-37 ADDITIONAL SECRETARIES 37-38 JOINT SECRETARIES 38-39 HEAD OF DEPARTMENTS 39-48 INFORMATION AND PUBLIC RELATIONS 48-51 POLICE DEPARTMENT 51-54 CORPORATIONS / BOARDS 55-68 COMMISSIONERS OF DIVISIONS 68 DEPUTY COMMISSIONERS 68-69 MAYORS & COMMISSIONERS OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS 69-70 CHAIRMAN DISTT. PLANNING COMMITTEE 71 UNIVERSITIES 72 PRESIDENT SECRETARIAT 73 VICE PRESIDENT SECRETARIAT 73 SUPREME COURT OF INDIA 73 ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA 73 NITI AAYOG 73 PRIME MINISTER OF INDIA 74 PARLIAMENT (RAJYA SABHA) 74 PARLIAMENT (LOK SABHA) 74 IAS & OTHER OFFICERS OF PB. POSTED AT DELHI 75 RESIDENT COMMISSIONER OFFICE AT NEW DELHI 76-77 CHANDIGARH ADMINISTRATION 77-78 OTHERS 78-80 PRESS, RADIO & TV 80-120 GUEST HOUSE/ENTERTAINMENT CENTRE (CHD) 120-121 CIRCUIT HOUSES IN PUNJAB & H.P. 121 EMERGENCY & GEN. UTILITY TEL. NO. AT CHD 121-123 SOME IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS AT DELHI 123-124 WEBSITES OF VARIOUS PUNJAB GOVT. DEPARTMENTS BOARDS, COPORATIONS, ETC. 124-125 OFFICIAL EMAIL ID’S OF THE DEPARTMENTS 125-132 STD CODES OF CITIES INDIA 138-143 *OEFY 1 Name & Designation Phone Residence Off. -

NZCC – List of Documentary Films

NORTH ZONE CULTURAL CENTRE, PATIALA LIST OF DOCUMENTARY FILMS * S. Name of the Documented Directed by Year Total State / Format of Present Format Contents No. Film of Duration Venue recording making (at the time of making) 1. Kullu Dussehra SBM Pictures, 1993 20.13 Himachal U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DV D A documentary film on Annual New Delhi Pradesh International Dussehra Festival of Kullu 2. National Craft Fair SBM Pictures, 1994 29.33 Chandigarh U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary film on Food & New Delhi Craft Mela organized at Leisure Valley, Chandigarh 3. Lohri Festival at R epublic Day SBM Pictures, 1994 26.27 Delhi U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary film on Lohri Folk Dance Festival -1994 New Delhi Festival celebrated during Republic Day Camp at Delhi 4. Basant Darbar at Patiala Dr. Atamjit 1994 20.35 Patiala U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD Live coverage of Classical Singh Music and Singing Programme 5. Baisakhi Mela SBM Pictures, 1994 23.00 Delhi U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary fi lm on New Delhi Baisakhi Celebration at Ashoka Hotel, New Delhi 6. Maha M oorakh Semmellan SBM Pictures, 1994 20.40 Bharatpur U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD Live coverage of Hasya Kavi New Delhi Sammelan 7. Patiala Gharana SBM Pictures, 1994 20.00 Patiala U-Matic DVC Pro -50 and DVD A documentary film on New Delhi Classical Music and Singing – Interview with Sh. Ajay Chakraborty * Record pertaining to the period before 1993 was irretrievably lost in the devastating floods in Patiala. -

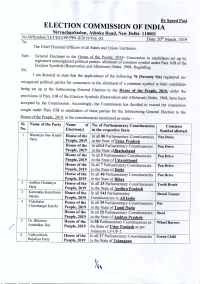

Allotment of Common Symbol Under 10B

By SpeedPost ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NirvachanSadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 No.56/SymboViLET/ECIIPP/PPS-II12019Nol._XI Date: 20th March, 2019 To, The Chief Electoral Officers of all States and Union Territories. Sub:- General Elections to the House of the People, 2019- Concession to candidates set up by registered unrecognized political parties- allotment of common symbol under Para lOB of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968- Regarding. Sir, I am directed to state that the applications of the following 76 (Seventy Six) registered un• recognized political parties for concession in the allotment of a common symbol to their candidates being set up at the forthcoming General Election to the House of the People, 2019, under the provisions of Para 10B of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, have been accepted by the Commission. Accordingly, the Commission has decided to extend the concession sought under Para 10B to candidates of these parties for the forthcoming General Election to the House of the People, 2019, in the constituencies mentioned as under: _ SI. Narne of the Party Name of No. of Parliamentary Constituencies Common No. Election(s) in the respective State Symbol allotted. 1 Bharatiya Nav Kranti House of the In all 80 Parliamentary Constituencies Pen Drive Party Peo_ple, 2019 in the State of Uttar Pradesh House of the In all14 Parliamentary Constituencies Pen Drive People, 2019 in the State ofJharkahand House of the In all 5 Parliamentary Constituencies Pen Drive People, -

Dr. Parmjeet Kaur ______

Dr. Parmjeet Kaur ____________________________________________________________________ Contact Information Assistant Professor (Punjabi), University College Benra, Dhuri, Distt. Sangrur (Pb). e-mail: parmjeet.pu @ gmail.com Mobile: 9914800204 Education credentials PhD degree under the supervision of Dr Uma Sethi, Panjab University Chandigarh (2007) PhD thesis title 'Dr Jaswant Singh Neki Da Nav Rahasvaadi Paripekh'. UGC NET held on June 1999 under roll no. B422149; Ref no. 2769/NET-June 99 (1999) M.A. (Anthropological linguistics & Punjabi language) from Punjabi University, Patiala (2011) M.A. (Punjabi) from Panjab University, Chandigarh (2009) B. Ed from Punjabi University, Patiala (1996) B.A. (Honours) from Panjab University, Chandigarh (1995) Experience Teaching - 13 years Research - 5 years Membership of Professional Bodies Punjabi Sahit Academy, Ludhiana (membership no. 1690) Book Nav Rahashvad Ate Neki Kav (2008), Lok Geet Prakashan Chandigarh. Invited Talk Ek Mahan Jodha: Guru Gobind Singh delivered on 25/3/2017 at Ramgarhia Girls College, Ludhiana. Articles/ Publications / Book Chapter Roof Da Zikar Na Karea Kar Deh Da Dukh Bathera Hai. Article, Rozana Desh Sewak, Chandigarh. Padarthan Di Daurh Vich Dam Torh Rahe Aman Chain. Article, Punjabi Tribune, Chandigarh. Khalsa Sirjana: Manav Chetana Da Nav Sankalp. Article, Rozana Chardi Kalan, Patiala. Lafza Di Dargah De Parsang Vich: Pattar Rachana, Book Chapter in the book Pattar Kav Chetana; edited by Dr. Guriqbal singh. Page 1 of 2 Gurcharn Kaur Thind Di Kahani Sangreh -

ANNEXURE a OFFICE of the DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE, JALANDHAR List of Candidates to Be Called for Interview F

ANNEXURE A OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE, JALANDHAR List of candidates to be called for interview for the post of Peon (including Peon, Orderly, Waterman, Chowkidar, Mali etc.) Father/ Husband Roll No. Candidate Name Date of Birth Address Name H.NO. 72-B, DILBAGH NAGAR, BASTI GUZAN, 1 PUNEET ARORA KIRAN ARORA 11-09-1988 JALANDHAR 2 BALJINDER SINGH GURSEWAK SINGH 05-11-1996 V.P.O CHARIK PATTI JANGIR DISTT. MOGA 3 AMARDEEP SINGH RAJINDER SINGH 16-06-1993 VPO SIRTHALA TEHSIL PAYAL DISTT. LUDHIANA 4 BUDH RAM BIRBHAN 05-08-1992 WNO. 6, NEAR BALMIK MANDIR, MOONAK,SANGRUR 5 MANDEEP SINGH BEER BHAN 15-05-1994 WNO. 6, MOONAK DISTT. SANGRUR WNO. 12, NEAR BALMIK TEMPLE, MOONAK, DISTT. 6 MANDEEP SINGH PAWAN KUMAR 16-04-1995 SANGRUR. COMMISSIONER COMPLEX NEAR NEW COURT. H.NO. 7 AMIT KUMAR SHARMA KEWAL RAM SHARMA 11-03-1992 DX691, JALANDHAR CITY 8 ANU MAKHAN PARSHAD 08-04-1995 20B, NEW BRADARI, JALANDHAR 9 BAHADUR SINGH PARAMJIT SINGH 14-07-1996 VPO KHUN-KHUN KALAN, HOSHIARPUR 10 RAMANDEEP SINGH GURJANT SINGH 31-08-1997 VILLAGE CHEEMA MOGA PUNJAB 11 MANVEER SINGH GURCHARAN SINGH 01-03-1997 VILLAGE GOGOANI, FEROZEPUR, PUNJAB H.NO. 208, VN PARK NANDANPUR ROAD, 12 KANHIEYA LALU PARSHAD 10-10-1996 MAQSUDAN, JALANDHAR 326-C, EKTA NAGAR, P.O CHUGTTI, NEAR TATA 13 VINOD SEMWAL CHAKARDHAR SEMWAL 20-04-1984 TOWER, JALANDHAR 14 BIPAN KUMAR SHRI LAL 02-02-1997 HNO.35, KIRTI NAGAR LADOWALI ROAD JALANDHAR 15 DALIP KUMAR SHREE LAL GUPTA 02-03-1999 HNO.35, KIRTI NAGAR LADOWALI ROAD JALANDHAR HNO.08,COURT ROAD WARD NO.9, NEAR WATER 16 SHUBH SH.AMRIK SINGH 11-09-1993 TANK NAKODAR DISTT.JALANDHAR 17 IQBAL SINGH MALKIT SINGH 03-01-1986 V.P.O. -

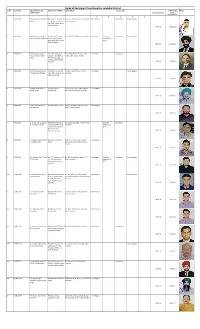

LATEST UPADATION 31.08.2021.Xlsb

Detail of Registered Travel Agents in Jalandhar District Sr.No. Licence No. Applicant Name and Office Name & Address Home Address Licence Type Till Which date Photo Father's Name Licence Issue Date Licence is Valid/Renewed 1 2 3 4 5 1 1/MC1/MA Sahil Bhatia S/o Sh. Manoj M/s Om Visa, Shop No.10, R/o H.No. 57, Park Avenue, Ladhewali Travel Agency Consultancy Ticekting Agent Bhatia 12, AGI Business Centre, Road, Jalandhar Near BMC Chowk, Garha Road, Jalandhar 04-09-15 03.09.2025 2 2/MC1/MA Mr. Bhavnoor Singh Bedi M/s Pyramid E-Services R/o H.No.127, GTB Avenue, Jalandhar Travel Agent Coaching Consultancy Ticekting Agent S/o Mr. Jatinder Singh Bedi Pvt. Ltd., 6A, Near Old Institution of Agriculture Office, Garha IELTS Road, Jalandhar 10-09-15 09.09.2025 3 3/MC1/MA Mr.Kamalpreet Singh M/S CWC Immigration R/o Village Alohran Khurd, Tehsil Travel Agent Consultancy Khaira S/o Kartar Singh Solutions, EH-124, Near Nabha, Distt. Patiala, Punjab. Khaira Anand market, Opp. FCI Godown, Ladowali Road, Jalandhar. 21-12-15 20-12-25 4 4/MC1/MA Sh. Rahul Banga S/o Late M/S Shony Travels, 2nd R/o 133, Tower Enclave, Phase-1, Travel Agent Ticketing Agent Sh. Durga Dass Bhanga Floor, 190-L, Model Town Jalandhar Market, Jalandhar 21-12-15 20-12-20 5 5/MC1/MA Sh.Jaspal Singh S/o Sh. M/S Cann. World Sco-307, 2nd Floor, Prege Chamber , Travel Agency Mohan Singh Consulbouds opp. -

Doctor of Philosophy

PARTICIPATION OF MUSLIM WOMEN IN THE SOCIO-CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES IN NORTH INDIA DURING THE 19TH CENTURY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY By SHAMIM BANO UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH, INDIA 2015 Dedicated To My Beloved Parents and my Supervisor Tariq Ahmed Dated: 26th October, 2015 Professor of History CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Participation of Muslim Women Socio-Cultural and Educational Activities in North India During 19th Century” is the original work of Ms. Shamim Bano completed under my supervision. The thesis is suitable for submission for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. (Prof. Tariq Ahmed) Supervisor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all I thank Almighty Allah, the most gracious and merciful, who gave me the gift of impression and insights for the compilation of this work. With a sense of utmost gratitude and indebtedness, I consider my pleasant duty to express my sincere thanks to my supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmed, who granted me the privilege of working under his guidance and assigned me the topic “Participation of Muslim Women in the Socio-Cultural and Educational Activities During the 19th Century in North India”. He found time to discuss various difficult aspects of the topic and helped me in arranging the collected data in the present shape. Thus, this research work would hardly have been possible without his learned guidance and careful supervision. I do not know how to adequately express my thanks to him. -

Punjabi Language and Dialects VII Oral Literature VIII Folk Music and Dances , APPENDIX BIBLIOGRAPHY ? INDEX

FOLKLj THE SOHINDER SINGH BEDI «5t / J \ • ft i * i o / r<)f D */«. "W* *t **a *<#f <*a FOLKLORE OF THE PUNJAB \ i folklore of India FOLKLORE OF THE PUNJAB Sohinder SinghjBedi • National Book Trust, India \ V First Edition 1971 (Saka 1893) Second Reprint 1991 (Saka 1913) © Sohinder Singh Bedi, 1971 Rs. 23.00 Published by the Director, National Book Trust, India, A-5, Green Park, New Delhi-110016 f -*» CONTENTS LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS ' Chapter I The Region and the People) i II Myth and Mythology III Magic and Religion IV Customs and Traditions , V Fairs and Festivals f VI Punjabi Language and Dialects VII Oral Literature VIII Folk Music and Dances , APPENDIX BIBLIOGRAPHY ? INDEX • / LI&T OF ILLUSTRATIONS A Rural Scene The Jewellery a Punjabi Girl is fond of A Nihang Singh in Traditional Costume I A Sister Tying Rakhi on the Wrist of Her Brother, A Holi Scene An Image of Sanjhi Devi • A Wandering Minstrel i A Giddha Dancer Close-up of a Bhangra Dancer ABhangra Dance A Piece of Folk-art A Scene from a Folk-dance Folk-artists at Work \ I r CHAPTER I THE ^REGION AND THE PEOPLE / "PUNJAB"—the land of five rivers—is proud of its ancient heritage. This is the cradle and breeding-place-of the Vedic culture of the Aryans. Rishis and munis composed the earliest hymns of the oldest book "in the world, the Rig Veda, on the banks of its rivers. Excavations of Harappa and Rupar reveal that even before the Aryans, a great civilization flourished here. -

Abstract Book

INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON SYMBOLISM IN INDIAN ART, ARCHAEOLOGY AND LITERATURE 1-3 December 2016 ABSTRACT BOOK Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, Pune (Deemed University) 1 Convener Prof. Vasant Shinde ViceChancellor, Deccan College Post-graduate and Research institute Deemed University, Pune-6 E-mail: [email protected] Coordinators Dr. Shrikant Ganvir, Department of AIHC and Archaeology E-mail: [email protected] Mr. Rahul Mhaiskar, Department of Linguistics E-mail: [email protected] Mr. Hari Palave, Department of Sanskrit and Lexicography E-mail: [email protected] Chief Guest Prof.Y. Sudershan Rao Guest of Honour Dr Senarath Dissanayake Keynote Speaker Dr. Kirit Mankodi ‘The Plunder of India’s Heritage’ Chancellor Prof. A. P. Jamkhedkar will preside over the function. This seminar is sponsored by the Indian Council of Historical Research. 2 Deccan College, Deemed University, Pune MESSAGE by Dr. A. P. Jamkhedkar, Chancellor I welcome all the delegates participating in the International Seminar on “Symbolism in Indian Art, Archaeology and Literature”. I wish this conference will discuss important research issues pertaining to symbolism of architecture, icons, artefacts, memorial stones, texts, paintings, folk cults, and will also provide an academic platform to the future generation.Symbolism of ancient culture is a significant aspect to comprehend multi-faceted dimensions of the past. I wish magnificent success of the conference. 3 4 Deccan College, Deemed University, Pune FOREWORD by Prof. Vasant Shinde, Vice-Chancellor I am pleased to welcome you all participating in the International Seminar on ‘‘Symbolism in Indian art, Archaeology and Literature’’. This seminar aims at discussing significance of symbolism in Indian art, archaeology and literature to reconstruct the cultural history of ancient India.